Three Social Studies Lessons Using Baseball as an Introduction to History

Developed by John Staudt

How Baseball and Jackie Robinson Shaped New York’s Identity

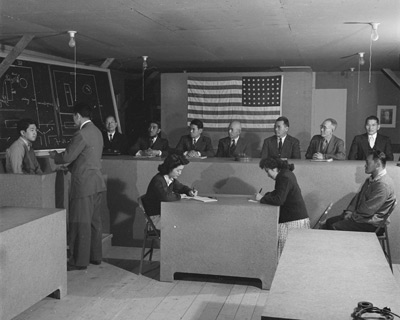

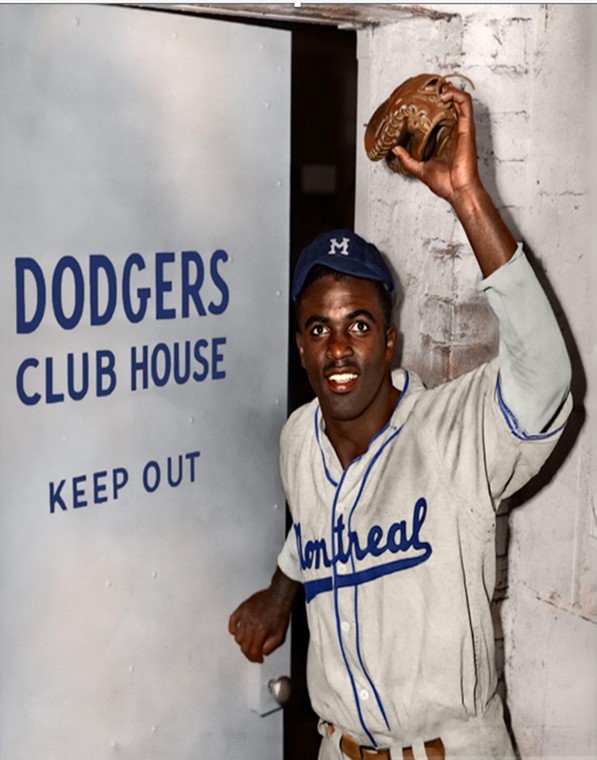

Jackie Robinson played with the Dodgers’ minor league Montreal team.

Introduction: The Brooklyn Dodgers were not just a baseball team; they were a cultural institution that embodied Brooklyn’s identity from 1883 until their departure in 1957. Prior to 1898, Brooklyn was the fourth largest city in America. After incorporation into the greater city of New York, the Dodgers contributed to Brooklynites maintaining their separate sense of identity. In 1947, Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. This historic moment changed not only baseball but also had profound social implications that shaped Brooklyn’s identity. After decades of falling short, particularly against the Yankees, the Dodgers finally won the World Series in 1955. This victory was a defining moment for Brooklyn’s collective identity. In 1957, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley moved the team to Los Angeles after failing to secure a deal to build a new stadium in Brooklyn. This departure left a profound impact on Brooklyn’s identity and development. The departure of the Dodgers coincided with other significant changes in Brooklyn and New York City. The borough’s identity had to evolve in the absence of its beloved team.

Questions

- In your opinion, what does the phrase “Wait ’til next year” reveal about Brooklyn’s character and the relationship between the team and its fans?

- Why was defeating the Yankees particularly significant for Brooklynites’ sense of identity?

- How did Brooklyn residents react to the Dodgers leaving Brooklyn?

- Do professional sports teams have any obligations to their loyal fanbase?

- The proposed site for a new Dodgers stadium at Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues eventually became the Barclays Center in 2012. What does the building of this arena reveal about Brooklyn’s evolution in your lifetime?

Jack Roosevelt Robinson: Baseball Pioneer and Civil Rights Activist Timeline

Pre-Integration Era (1865-1946)

- 1865-1877: Reconstruction era provides brief period of expanded rights for Black Americans. Republican support among Black voters, however, declines when President Hayes withdrew federal troops from the South

- 1876: National League founded (all-white)

- 1884: Moses Fleetwood Walker becomes last Black player in major leagues prior to International League institutes unwritten “gentlemen’s agreement” (1887) barring Black players

- 1920s: Negro National League established as segregated professional baseball thrives

- 1939: Jackie Robinson enrolls at UCLA, becomes first athlete to letter in four sports

- 1944: Robinson court-martialed for refusing to move to back of segregated bus while in Army

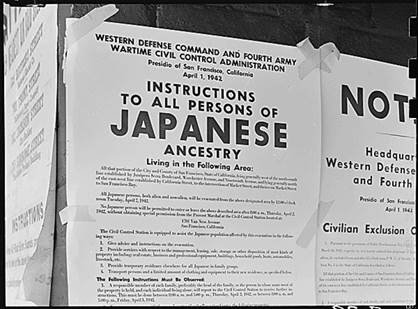

- 1945: Branch Rickey signs Robinson to Montreal Royals (Dodgers’ farm team). Robinson agrees to avoid responding to provocations from racist white fans and players

- 1946: Robinson leads International League with .349 average and 40 stolen bases

Breaking the Color Barrier (1947-1956)

- April 15, 1947: Robinson debuts with Brooklyn Dodgers

- 1948: President Truman issues Executive Order 9981 desegregating armed forces

- 1949: Robinson wins NL MVP, batting .342 with 37 stolen bases

- 1954: Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision outlawed school segregation

- 1955: Rosa Parks, MLK and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

- 1955: Robinson helps Dodgers win World Series

- 1956: Robinson retires from baseball rather than accept trade to Giants

Post-Baseball Activism (1957-1972)

- 1957: Robinson is hired as VP at Chock Full O’Nuts

- 1957: Robinson heads NAACP Fund Drive

- 1957: Little Rock Nine integrate Central High School in Arkansas

- 1959: Robinson begins writing syndicated newspaper columns

- 1960: Robinson campaigns for Richard Nixon in presidential election

- 1963: Robinson participates in March on Washington with MLK

- 1964: Robinson co-founds Freedom National Bank in Harlem

- 1964: Civil Rights Act passed

- 1965: Voting Rights Act passed

- 1968: Robinson supports Hubert Humphrey after disillusionment with Republican Party

- 1970: Robinson creates Jackie Robinson Construction Corporation

- October 15, 1972: Final appearance at World Series, calls for Black MLB managers

- October 24, 1972: Robinson dies at age 53 from heart attack and diabetes complications

Legacy (1973-Present)

- 1973: Rachel Robinson establishes Jackie Robinson Foundation

- 1997: MLB universally retires Robinson’s number 42

- 2004: MLB establishes Jackie Robinson Day (April 15)

Timeline Critical Thinking Questions:

- What economic, cultural, or social factors might have made baseball more willing to accept racial integration before other American Institutions?

- Why did MLB’s integration have such a profound impact on American society?

Robinson in Historical Context

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson played first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field, becoming the first Black player in Major League Baseball since 1884. The Dodgers defeated the Boston Braves 5-3. This historic moment ended the “gentlemen’s agreement” among team owners that had kept baseball segregated. Robinson’s journey began when Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager, signed him to the Montreal Royals (the Dodgers’ minor league affiliate) in 1945. Rickey specifically chose Robinson not only for his athletic ability and competitive fire but for his character and temperament, asking him to “turn the other cheek” in the face of racial hostility. After excelling in Montreal during the 1946 season, Robinson joined the Dodgers for the 1947 season. Robinson’s debut received dramatically different coverage in white and Black newspapers. Most mainstream white papers barely mentioned the historic significance, focusing instead on other aspects of the game. In contrast, Black newspapers across the country made Robinson’s debut front-page news, with extensive coverage and photography.

Throughout his first season, Robinson endured racist taunts, pitches thrown at his head, and opponents attempting to spike him on the basepaths. Despite this, he batted .297, led the league in stolen bases, and won the first Rookie of the Year award. His decade-long career included six National League pennants, a World Series championship in 1955, and the National League MVP award in 1949. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962.

Robinson was politically engaged throughout his post-baseball life. He served as chairman of the NAACP Freedom Fund Drive, traveling the country to recruit members and raise funds. From 1959, he wrote syndicated newspaper columns addressing race relations, politics, and other social issues for the New York Post and later the New York Amsterdam News. Robinson developed close relationships with civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., whom he accompanied on numerous speaking tours. Robinson supported King’s work and helped raise funds for the Civil Rights Movement. Specifically, he and his wife Rachel hosted jazz concerts at their Connecticut home to raise bail money for protesters arrested during civil rights Robinson’s impact on civil rights was summarized by Martin Luther King Jr., who told Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe: “You will never know how easy it was for me because of Jackie Robinson.” Robinson’s approach to civil rights combined direct advocacy with practical action. Robinson believed that speaking out against injustice was a responsibility that came with his privileged celebrity position, frequently stating he would not remain silent when witnessing wrongdoing. He challenged professional sports leagues, politicians, and fellow athletes to do better on racial issues throughout his life.

After retiring from baseball in 1956, Robinson became vice president of personnel at Chock Full O’Nuts, becoming the first African American to hold such a position at a major American corporation. He used this platform to advocate for civil rights, writing letters to politicians on company letterhead and challenging discriminatory practices. Robinson believed strongly in economic independence for Black Americans. He co-founded the Freedom National Bank in Harlem in 1964 to provide financial services to the Black community, and in 1970 he created the Jackie Robinson Construction Corporation to build affordable housing. He consistently advocated for Black capitalism and criticized businesses that failed to employ African Americans.

In presidential politics, Robinson initially supported Hubert Humphrey in the 1960 Democratic primaries before backing Republican Richard Nixon in the general election, believing Nixon had a stronger civil rights record than John Kennedy. Later, he campaigned for progressive Republican candidate Nelson Rockefeller and opposed Barry Goldwater’s 1964 Republican nomination, which he felt represented a rightward shift that would attract more white voters by alienating Black voters. By 1968, disillusioned with Nixon, he supported Humphrey again.

At his final public appearance at the 1972 World Series, just nine days before his death, Robinson used the opportunity to call for more Black managers and coaches in baseball. After his death from a heart attack on October 24, 1972, civil rights activist Jesse Jackson delivered his eulogy, calling him “the Black Knight in a chess game… checking the King’s bigotry and the Queen’s indifference.” In 1973, Rachel Robinson established the Jackie Robinson Foundation, which provides scholarships and support services to minority students. By 2021, the foundation had graduated over 1,500 students, maintained a nearly 100% graduation rate, and provided more than $70 million in assistance. The Jackie Robinson Museum in New York City was created to further preserve his legacy. Robinson’s own quote, engraved on his tombstone, captures his philosophy: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” Through both his baseball career and his activism, Jackie Robinson’s life embodied this principle, changing American sports and society forever.

Robinson and Black Voters

As “the Party of Lincoln,” Republicans had delivered emancipation, the Reconstruction Amendments (13th, 14th, and 15th), and various civil rights acts from 1866 to 1875. However, this alignment between Republicans & Black Americans began to fracture after Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes ended Reconstruction by withdrawing federal troops from the South in 1877. In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal attracted Black voters to the Democratic Party.

In 1960, Robinson supported Richard Nixon over John Kennedy. This choice reflected Robinson’s approval of the Eisenhower administration’s deployment of federal troops to protect Black students in Little Rock and passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act. At that time, Nixon’s civil rights record appeared stronger than Kennedy’s or Johnson’s.

As an executive at Chock Full O’Nuts, Robinson championed Black economic self-sufficiency, believing that Black-owned businesses and financial institutions were crucial for community advancement. This economic philosophy aligned with traditional Republican values. Robinson’s party loyalty evolved as the political landscape shifted. He supported Democrat Lyndon Johnson over Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964 after Goldwater opposed that year’s Civil Rights Act. By 1968, Robinson had broken with Nixon and voted for Democrat Hubert Humphrey. By 1972, the year of Robinson’s death, Democrat George McGovern won 87% of the Black vote —a percentage that has remained consistent in subsequent elections, demonstrating the complete reversal of Black voters’ historical party alignment.

Robinson’s Vision of Black Capitalism

After retiring from baseball in 1956, he moved into the business world and increasingly focused on economic advancement for Black Americans as a pathway to greater equality. Robinson became the first Black vice president of a major American corporation when he joined Chock Full O’Nuts in 1957. He used this platform to advocate for racial equality and demonstrate that Black Americans could excel in corporate leadership. In 1964, Robinson co-founded Freedom National Bank in Harlem. He believed Black-owned banks were essential to provide capital to communities that had been traditionally excluded from mainstream financial services. As Rachel Robinson noted, the bank was “probably one of his major post-baseball achievements” because it allowed people to “get mortgages” and “small businesses could begin to get loans.” In 1970, Robinson established the Jackie Robinson Construction Company to build affordable housing for low-income families. He saw housing as a critical component of economic stability and community development. Robinson combined his economic initiatives with direct political activism. He corresponded regularly with political leaders, participated in civil rights marches with Martin Luther King Jr., and used his business platforms to advocate for broader social change. Robinson believed in simultaneously pursuing political equality and economic advancement. He saw economic power as a necessary companion to political rights.

In his approach Robinson built on several core beliefs and principles established 60 years earlier by Black economic equality activists such as Booker T. Washington. Both men emphasized the importance of Black economic independence and viewed entrepreneurship as essential for advancement. Both created or supported Black-owned institutions that could serve community needs without relying on white approval or support. Both valued practical education that could translate directly into economic opportunities. Both saw Black-owned businesses as vehicles for community development and racial advancement. Both believed that demonstrating Black capability and success would help undermine racist stereotypes and arguments.

Despite these similarities, there were crucial differences in their approaches. Robinson saw economic initiatives as complementary to—not a replacement for—the fight for immediate civil and political rights. Robinson actively challenged segregation and participated in direct civil rights activism alongside his economic initiatives. Robinson directly challenged racial inequities, even when it alienated white supporters. As Robinson stated, he was “very much concerned over the lack of understanding in White America of the desires and ambitions of most Black Americans.” Robinson pursued integration across both social and economic spheres. As Robinson experienced the limitations of Black political advancement, he intensified his focus on economic institutions. Robinson’s economic vision expanded from individual advancement to community-wide initiatives that could create systemic change.

Robinson’s approach to Black capitalism influenced later civil rights leaders who recognized the importance of economic power alongside political rights. His founding of Freedom National Bank was a pioneering step in the community development banking movement. The bank served as the financial backbone of Harlem into the 1990s. In many of his actions and words, Robinson further developed the idea that economic empowerment without political rights is insufficient, but that political rights without economic power remains incomplete.

Historical Context Questions

- How was Major League Baseball’s “Gentlemen’s Agreement” supported by social, legal and economic factors?

- Explain how Robinson’s post-baseball activities reflected his commitment to economic justice for Black Americans.

- Robinson said, “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” Identify three specific ways Robinson impacted American society beyond sports.

- Compare and contrast Jackie Robinson’s approach, tactics, philosophies, to other prominent civil rights figures (Paul Robeson, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, etc.).

- What do Robinson’s shifting endorsements of Republican and Democratic candidates reveal about the politics of civil rights?

- How have recent events in sports and society continued Robinson’s legacy of athlete activism?

- Examine how Robinson’s story has been memorialized, commemorated, and sometimes sanitized with the removal of controversy in American public memory.

Critical Analysis Questions

As students of history, examining primary sources allows us to understand historical figures in their own context rather than solely through the lens of later interpretations. Robinson’s words reveal the complex interplay between his baseball career, civil rights activism, and political engagement.

Robinson’s Letter to President Eisenhower (May 13, 1958): Robinson wrote this letter on Chock Full O’Nuts letterhead to express his disappointment with President Eisenhower’s advice that Black Americans should be patient in their quest for civil rights. By this time, Robinson had been retired from baseball for two years and was using his position as a corporate executive to advocate for civil rights.

“I was sitting in the audience at the Summit Meeting of Negro Leaders yesterday when you said we must have patience… On behalf of myself, and I know thousands and thousands of my fellow Americans, I respectfully remind you sir that we have been the most patient of all people.”

Questions

- How does Robinson’s tone and words differ from his public persona during his playing days?

- What does Robinson’s use of corporate letterhead suggest about his business position and his activism?

- How might Robinson’s letter have influenced Dr. King’s 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” What risks did Robinson and King face in writing their letters?

“I Never Had It Made” Autobiography (1972): Published in the year of his death, Robinson’s autobiography presented a more critical and candid perspective on American racism than he had publicly expressed during much of his baseball career. This statement reflects his evolving views on patriotism and racial progress.

“I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a Black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.”

Questions

- How does this statement challenge simplified narratives about Robinson as a symbol of American progress? Why might Robinson have felt more comfortable expressing these views in 1972 than earlier in his baseball career?

- Compare Robinson’s perspective with athlete activism today. What parallels and differences can you make?

Robinson on Economic Justice (New York Amsterdam News, 1962): Robinson wrote regular columns for the New York Amsterdam News, a prominent Black newspaper. In these columns, he advocated for economic opportunities for Black Americans and challenged discriminatory practices in business and sports.

“It is the duty and responsibility of each and every one of us to refuse to accept the faintest sign or token of prejudice. It does not matter whether it is directed against us or against others. Racial prejudice is not only a vicious disease, it is contagious.”

Questions

- How did Robinson’s economic perspectives and activities promote civil rights?

- How did Robinson’s status as a former athlete and business executive shape his particular form of civil rights activism?

Robinson’s Final Public Statement (October 15, 1972): This statement came nine days before Robinson’s death during a ceremony honoring the 25th anniversary of his breaking baseball’s color barrier. Despite the celebratory occasion, Robinson used the platform to highlight ongoing inequalities in Major League Baseball.

“I’d like to see a Black manager. I’d like to see the day when there’s a Black man coaching at third base.”

Questions

- What does this statement reveal about Robinson’s assessment of baseball’s progress on racial equality since 1947? Why would Robinson choose this particular moment to highlight the status of Black Athletes? How does it add to the statements historical significance?

- How long did it take for Robinson’s wish to be fulfilled? What does this reveal about institutional resistance to social change? What does this reveal about Robinson’s impact on Baseball and American society?

Culminating assignment: Write a paragraph essay addressing one of the following prompts:

- How did the Brooklyn Dodgers both reflect and shape Brooklyn’s identity and how did their departure impact the region? Use specific examples for both.

- What lessons can be learned from the Dodgers story about the relationship between sports teams or cultural institutions and a community’s identity? Provide one modern example.

Resources and Bibliography

- The Jackie Robinson Foundation Archives

- Papers of the NAACP (Library of Congress)

- Robinson, Jackie. I Never Had It Made (autobiography)*

- Robinson, Rachel. Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait*

- Tygiel, Jules. Baseball’s Great Experiment

- Long, Michael G. First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson

- Rampersad, Arnold. Jackie Robinson: A Biography

- Long, Michael. 42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy

- Long, Michael G. First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson

- Burns, Ken. Jackie Robinson (documentary)

Chavez Ravine: From Barrio to Dodger Stadium

This worksheet is based on an article originally published by PBS American Experience, written by Eduardo Obregón Pagán.

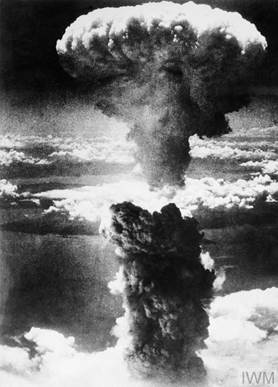

In the shadows of Los Angeles’ urban development lies the story of Chavez Ravine, a once-thriving Mexican-American community sacrificed for the creation of Dodger’s Stadium. This rural enclave near downtown Los Angeles maintained a tight-knit, self-sufficient character despite lacking basic city services. Residents grew their own food, raised livestock, and fostered strong community bonds through local institutions like their Catholic church, elementary school, and neighborhood businesses.

The community’s fate changed dramatically in the post-World War II era. Initially, Chavez Ravine was designated for a federally-funded public housing development. Residents were forced to sell their homes at below-market prices with promises they would receive priority housing in the new development. Many families complied, believing the government’s promises.

However, the story took a decisive turn when Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley sought a new location for his team. Los Angeles investors, eager to attract a major sports franchise, offered Chavez Ravine as the perfect stadium site. In the politically charged McCarthy era, city leadership abandoned the housing project, labeling it as too “communist,” and voters approved the stadium plan in a referendum.

Community resistance formed as remaining residents organized, created petitions, and testified at city meetings about their rights to their homes and land. Their efforts ultimately failed when, on May 9, 1959 – known as “Black Friday” – sheriff’s deputies forcibly removed the last families from their homes. Bulldozers quickly moved in, destroying all traces of the once-vibrant neighborhoods. The promised replacement housing never materialized for those who had initially complied with orders to sell their properties.

Dodger Stadium rose from these ruins, becoming a celebrated landmark for baseball fans while simultaneously standing as what many consider “a monument to the power of wealth over the impoverished.” The stadium represents the racialized nature of urban renewal policies and the unjust displacement of marginalized communities in favor of commercial interests.

This history demonstrates several significant patterns that continue to resonate in American urban development: racial and economic injustice in planning decisions, broken promises to vulnerable communities, tensions between public housing needs and commercial development, and the erasure of marginalized histories from popular narratives. From a legal perspective, O’Malley & The Dodgers operated within existing law – the land acquisition occurred through government processes, was approved by voters, and evictions were executed by law enforcement. However, ethical questions linger about a process that exploited residents with limited political power and the acceptance of land obtained through broken promises. The story of Chavez Ravine remains relevant today as cities continue to wrestle with questions of development, displacement, gentrification, and whose interests take priority in urban planning decisions.

The story of Chavez Ravine’s transformation from a Mexican-American community to the site of Dodger Stadium represents one of baseball’s most complex historical chapters, yet it remains unfamiliar to many fans and virtually erased from the popular baseball narrative. Baseball’s dominant stories traditionally focus on on-field achievements.. The mythology of Dodger Stadium emphasizes its picturesque setting, perfect sightlines, and the excitement of the Dodgers’ arrival in Los Angeles rather than examining the displacement that preceded it. When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958, the media celebrated the economic benefits and civic pride the team would bring rather than investigating the local community costs.

Additionally, baseball’s gatekeepers (team and league officials, journalists, TV & marketing execs, and fans) have traditionally reflected baseball’s power structures. The voices and perspectives of displaced Mexican-American residents had little representation in the game’s official story.

More recently, as sports history has become more inclusive and critical, the Chavez Ravine story has gained increased attention through academic studies, documentaries, and community remembrance projects. However, these efforts remain peripheral to mainstream baseball coverage, which continues to celebrate ballparks without fully acknowledging any complicated origins.

For baseball to fully reckon with this history would require confronting uncomfortable questions about who benefits from and who pays the price for the growth of the sports industry across the world – a conversation that challenges the game’s preferred self-image as an innocent pastime above politics and social conflict.

Critical Thinking Questions:

- How has baseball’s storytelling traditions (which emphasizes baseball’s positive impact on communities) contributed to the erasure of the Chavez Ravine displacement story?

- How might the Chavez Ravine controversy further complicate Walter O’Malley’s legacy in New York’s baseball history?

- What does the Dodgers departure from Brooklyn and their relocation to LA teach us about community dynamics and professional sports teams business decisions?