Black Lives that Mattered

Alan Singer

Teachers are grappling with ways to develop a more culturally-responsive social studies curriculum. An excellent starting point for revising the United States history curriculum overall is Voices of a People’s History, a document collection by Howard Zinn and Anthony Arnove that is a companion to Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. Voices includes African American spokespeople from a number of eras. Featured Black abolitions include David Walker (1830), Henry Bibb (1844), Frederick Douglass (1852), Sojourner Truth (1851), and Harriet Jacobs (1861). Civil Rights activists include Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1893), Langston Hughes (1951), Paul Robeson (1956), John Lewis (1963), Malcolm X (1963), Fannie Lou Hamer (1964), Martin Luther King (1967), and Anne Moody (1968). More recent speakers and writers include George Jackson (1970), Angela Davis (1970), Assata Shakur (1978), Marian Wright Edelman (1983), Public Enemy (1990), June Jordan (1991), Mumia Abu-Jamal (2001), and Danny Glover (2003). Important websites for adding Black achievements to in the United States to the curriculum are:

When teachers are resistant to change, “awoke” students have a role to play. Social Studies lessons are usually organized so students can answer essential or compelling historical or contemporary questions. Many teachers start the lesson with an AIM question that defines the lesson and often also serves as a summary question at the end of lesson. If teachers aren’t asking these questions, students can politely ask them during the course of a lesson. “I don’t understand”:

- What role did the trans-Atlantic slave trade play in the settlement of the Americas?

- How could the signers of the Declaration of Independence proclaim “all men are created equal” and then keep almost 20% of the population enslaved?

- Is the wealth of the United States and its position in the world today based on the enslavement of Africans?

- How did Frederick Douglass feel about the American celebration of July 4th?

- Why did Abraham Lincoln promise the South they could keep Africans enslaved?

- To whom did Abraham Lincoln offer “malice toward none” and “charity for all”?

- How could the Supreme Court in the 1850s, the 1880s, and the 1890s blindly ignore what the Constitution says about equal rights?

- Why did the federal government abandon Blacks after the Civil War and Reconstruction?

- Why were American troops racially segregated in World War I and World War II?

- Why did Martin Luther King ask “What is to be done?” after passage of the 1960s Civil Rights acts?

- Why do housing and job discrimination and school segregation continue in the 21st century?

- Why do so many Black men and women continue to be injured or killed by police?

These activity sheets introduce students to thirteen African Americans who made major contributions to American democracy, but who are normally not included in the United States history curriculum. Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman, Julia Williams Garnet, Henry Highland Garnet, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Elizabeth Jennings Graham, Sarah Tompkins Garnet, Susan McKinney Steward, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, W.E.B. DuBois, A. Philip Randolph, Paul Robeson, Ralph Bunche, and Fanny Lou Hamer are in chronological order based on the year of their birth. An examination of these lives introduces students to major themes in African American and United States history, as well as to “Black Lives that Mattered.”

Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman (c. 1744-1829): A Black Life that Mattered

Statue of Elizabeth Freeman, National Museum of African American History and Culture. An important source is the Ashley House historic site website. https://thetrustees.org/content/elizabeth-freeman-fighting-for-freedom/

Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman was born enslaved in Claverack, New York in present day Columbia County. As a teenager she was sold to Colonel John Ashley and moved to his property in western Massachusetts near Great Barrington where she was kept enslaved for thirty years. In the 1770s, Mum Bett overheard conversations about revolutionary unrest in Massachusetts, challenges to British colonial rule, the Declaration of Independence, and a new Massachusetts constitution. Her decision to sue in court for freedom was probably in response to abuse by Mrs. Ashley. Mum Bett intervened when Hannah Ashley tried to hit another enslaved woman, who might have been Mum Bett’s sister or daughter, with a kitchen shovel. Mum Bett was hit instead in the face and was scarred. After the attack, Mum Bett sought help to escape slavery from Theodore Sedgwick, a lawyer in Stockbridge.

In 1780, Massachusetts adopted a state constitution that was largely drafted by future President John Adams. It drew on the promise of equality and liberty made in the Declaration of Independence and included a Bill of Rights that declared “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights.

With Sedgwick’s help, Mum Bett sued for freedom in a Massachusetts Court of Common Pleas. In Brom and Bett v. Ashley, a local jury found that Mum Bett and another enslaved African, Brom, were legally free people and awarded them 30 shillings in damages. In 1781, the jury’s decision was affirmed by the Massachusetts Supreme Court and in 1783, citing its decision in Brom and Bett v. Ashley, the state’s Supreme Court declared slavery a violation of the Massachusetts state constitution. After securing her freedom, Mum Bett chose the name Elizabeth Freeman. John Ashley offered to hire her as a paid employee, but she refused to work for the family again.

Documents:

Sheffield Resolves (Sheffield, Massachusetts, 1773): “RESOLVED: That mankind in a state of nature are equal, free and independent of each other and have a right to the undisturbed enjoyment of their lives, their liberty and property.”

Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Article I: “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.”

https://malegislature.gov/laws/constitution

Chief Justice William Cushing charge to the jury in case of Quok Walker (1781): “As to the doctrine of slavery and the right of Christians to hold Africans in perpetual servitude, and sell and treat them as we do our horses and cattle, that (it is true) has been heretofore countenanced by the Province Laws formerly, but nowhere is it expressly enacted or established . . . But whatever sentiments have formerly prevailed in this particular or slid in upon us by the example of others, a different idea has taken place with the people of America, more favorable to the natural rights of mankind, and to that natural, innate desire of Liberty, with which Heaven (without regard to color, complexion, or shape of noses — features) has inspired all the human race. And upon this ground our Constitution of Government, by which the people of this Commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves, sets out with declaring that all men are born free and equal – and that every subject is entitled to liberty, and to have it guarded by the laws, as well as life and property – and in short is totally repugnant to the idea of being born slaves. This being the case, I think the idea of slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution; and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature, unless his liberty is forfeited by some criminal conduct or given up by personal consent or contract.”

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h38t.html

Massachusetts Supreme Court Ruling (1783): “These sentiments led the framers of our constitution of government – by which the people of this commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves to each other – to declare – that all men are born free and equal; and that every subject is entitled to liberty, and to have it guarded by the laws as well as his life and property. In short, without resorting to implication in constructing the constitution, slavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be by the granting of rights and privileges wholly incompatible and repugnant to its existence.”

Elizabeth Freeman’s Statement on Freedom: “Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me & I had been told I must die at the end of that minute I would have taken it — just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman — — I would.”

https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/01/27/elizabeth-freeman-sheffield-slave-ashley-sedgwick

Epitaph on Elizabeth Freeman’s grave stone (Stockbridge, MA): ELIZABETH FREEMAN known by the name of MUMBET Died Dec 28, 1829 Her supposed age was 85 Years. She was born a slave and remained a slave for nearly thirty years. She could neither read nor write, yet in her own sphere she had no superior nor equal. She neither wasted time nor property. She never violated a trust, nor failed to perform a duty. In every situation of domestic trial, she was the most efficient helper, and the tenderest friend. Good Mother, farewell.

https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/01/27/elizabeth-freeman-sheffield-slave-ashley-sedgwick

Julia Williams Garnet (1811-1870): A Black Life that Mattered

Julia Williams was an African-American abolitionist who was active in Massachusetts, New York, Jamaica, and Washington DC. Williams was born free in Charleston, South Carolina and as a child moved with her family to Boston. While she did not leave her own written record, she often collaborated with her husband, Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, on his speeches and writings. Her life touched on a number of major abolitionist organizations and events. Williams was a student at both the Canterbury Female Boarding School in Connecticut and the Noyes Academy in Canaan, New Hampshire. Canterbury was a school for “young Ladies and little Misses of color.” Noyes had an interracial student body. Both schools were attacked by white mobs while she was attending and forced to close. Williams finally completed her education at the abolitionist run Oneida Institute in New York. Williams later was a member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, attended the 1837 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in New York, was a missionary in Jamaica where she headed an industrial school for girls, and after the Civil War worked with freedmen in Washington, DC.

Documents:

The Liberator Report on the Destruction of Noyes Academy (1835)

Source: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/19369301/noyes-academy-removal-criticism/

“The Superintending Committee appointed by said town to remove the ‘Noyes Academy’ proceeded at 7 o’clock, A.M of the 10th inst. [August 10] to discharge their duty; the performance of which they believe the interest of the town, the honor of the State, and the good of the whole community (both black and white) required without delay. At an early hour, the people of this town and of the neighboring towns assembled, full of the spirit of ’75 [sic], to the number of about three hundred, with between ninety and one hundred yoke of oxen, and with all necessary materials for the completion of the undertaking. Many of the most respectable and wealthy farmers of this and the adjacent towns rendered their assistance on this occasion . . . The work was commenced and carried on with very little noise, considering the number engaged, until the building was safely landed on the common near the Baptist meeting-house, where it stands, . . . the monument of the folly of those living spirits, who are struggling to destroy what our fathers have gained.

Address of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (1836)

Source: www.Docsteach.Org/Documents/Document/Address-Boston-Antislavery-Society?Tmpl=Component&Print=1

“As women, it is incumbent upon us, instantly and always, to labor to increase the knowledge and the love of God that such concentrated hatred of his character and laws may no longer be so entrenched in men’s business and bosoms that they dare not condemn and renounce it. As wives and mothers, as sisters and daughters, we are deeply responsible for the influence we have on the human race. We are bound to exert it; we are bound to urge men to cease to do evil, and learn to do well. We are bound to urge them to regain, defend, and preserve inviolate the rights of all, especially those whom they have most deeply wronged. We are bound to the constant exercise of the only right we ourselves enjoy — the right which our physical weakness renders peculiarly appropriate — the right of petition. We are bound to try how much it can accomplish in the District of Columbia, or we are as verily guilty touching slavery as our brethren and sisters in the slaveholding States: for Congress possesses power ‘to exercise exclusive legislation over the District of Columbia in all cases whatsoever,’ by a provision of the Constitution; and by an act of the First Congress, the right of petition was secured to us.”

An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, Issued by an Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women (1837)

Source: https://archive.org/stream/appealtowomenofn00anti/appealtowomenofn00anti_djvu.txt

The women of the North have high and holy duties to perform in the work of emancipation — duties to themselves, to the suffering slave, to the slaveholder, to the church, to their country, and to the world at large; and, above all, to their God. Duties which, if not performed now, may never be performed at all . . . Many regard the excitement produced by the agitation of this subject as an evidence of the impolicy of free discussion, and a sufficient excuse for their own inactivity. Others so undervalue the rights and responsibilities of woman, as to scoff and gainsay whenever she goes forth to duties beyond the parlor and the nursery . . . Every citizen should feel an intense interest in the political concerns of the country, because the honor, happiness, and well-being of every class, are bound up in its politics, government and laws. Are we aliens because we are women? Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives, and daughters of a mighty people? Have women no country — no interest staked in public weal — no liabilities in common peril — no partnership in a nation’s guilt and shame? . . . Moral beings have essentially the same rights and the same duties, whether they be male or female. This is a truth the world has yet to learn, though she has had the experience of fifty-eight centuries by which to acquire the knowledge of this fundamental axiom. Ignorance of this has involved her in great inconsistencies, great errors, and great crimes, and hurled confusion over that beautiful and harmonious structure of human society which infinite wisdom had established.

Henry Highland Garnet (1815-1882): A Black Life that Mattered

This biography of Henry Highland Garnet is drawn from a number of online sources and New York and Slavery: Time to Teach the Truth (SUNY, 2008). It concludes with excerpts from Garnet’s 1843 speech at a National Negro Convention in Buffalo, New York. In the speech, Garnet called for active resistance to slavery.

Henry Highland Garnet was born to enslaved parents in Kent County, Maryland in 1815. In 1824, his parents received permission to attend a funeral and used it as an opportunity to escape to New Jersey. The Garnets arrived in New York City in 1825, where Henry entered the African Free School on Mott Street. After a sea voyage to Cuba as a cabin boy in 1829, Henry returned to New York where he learned that his family had separated in a desperate effort to evade slave catchers. Enraged and worried, Garnet wandered up and down Broadway with a knife. Eventually friends were able to arrange refuge for him with abolitionists on Long Island.

In 1835, while he was attending the interracial Noyes Academy in Canaan, New Hampshire, a mob destroyed the school and attacked the house where Garnet and the other Black students were living. They fought back but were eventually forced to flee the town. Garnet later graduated from Oneida Institute near Utica, New York and in 1842, he became a pastor of the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church in Troy, New York. While there, Garnet edited abolitionist newspapers which called for enslaved Blacks to rise up in rebellion. He joined the Liberty Party and was known as an effective orator, but more mainstream abolitionists like Frederick Douglass thought he was too radical. In a speech to the National Negro Convention, Garnet urged enslaved Africans to rebel against their chains because they were better off dying free than living as slaves. In the 1850s, he became a missionary in Jamaica and encouraged Blacks to move there. During the Civil War, Garnet was a minister at the Shiloh Presbyterian Church in Manhattan and chaplain for Black troops stationed at Riker’s Island. In July 1863, draft rioters stalked Garnet, forcing his family to hide with neighbors. Later in his career, Garnet founded the African Civilization Society and advocated migration to a West African colony in Yoruba. In 1881, he was appointed a United States representative to Liberia

In an 1843 speech at a National Negro Convention in Buffalo, New York, Henry Highland Garnet beseeched his enslaved brethren to “Awake, awake; millions of voices are calling you! Your dead fathers speak to you from their graves. Heaven, as with a voice of thunder, calls on you to arise from the dust. Let your motto be resistance! resistance! resistance! No oppressed people have ever secured their liberty without resistance.”

Document: Henry Highland Garnet Calls for Resistance! (1843)

“Brethren, it is as wrong for your lordly oppressors to keep you in slavery, as it was for the man thief to steal our ancestors from the coast of Africa. You should therefore now use the same manner of resistance, as would have been just in our ancestors, when the bloody foot-prints of the first remorseless soul-thief was placed upon the shores of our fatherland. The humblest peasant is as free in the sight of God as the proudest monarch. Liberty is a spirit sent out from God and is no respecter of persons. Brethren, arise, arise! Strike for your lives and liberties. Now is the day and the hour. Let every slave throughout the land do this, and the days of slavery are numbered. You cannot be more oppressed than you have been, you cannot suffer greater cruelties than you have already. Rather die freemen than live to be slaves. Remember that you are four millions!”

“In the name of God, we ask, are you men? Where is the blood of your fathers? Has it all run out of your veins? Awake, awake; millions of voices are calling you! Your dead fathers speak to you from their graves. Heaven, as with a voice of thunder, calls on you to arise from the dust. Let your motto be resistance! resistance! resistance! No oppressed people have ever secured their liberty without resistance. Trust in the living God. Labor for the peace of the human race, and remember that you are four millions.”

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911): A Black Life that Mattered

Source: https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/frances-ellen-watkins-harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was an abolitionist, poet, novelist, suffragist, lecturer, teacher and reformer who co-founded the National Association of Colored Women. She was born to free Black parents in Baltimore, Maryland during the era of slavery. When she was 26, she became the first female instructor at Union Seminary, a school for free African Americans in Wilberforce, Ohio. She published her first book of poetry when she was twenty years old and her anti-slavery poetry was printed in the abolitionist press. While living in Philadelphia in the 1850s, she assisted freedom seekers escaping on the Underground Railroad. In May 1866,Frances Ellen Watkins Harper addressed the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in New York City. Other speakers included white suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucretia Mott.

Documents:

Eliza Harris (Excerpt) https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52447/eliza-harris

Like a fawn from the arrow, startled and wild,

A woman swept by us, bearing a child;

In her eye was the night of a settled despair,

And her brow was o’ershaded with anguish and care.

She was nearing the river—in reaching the brink,

She heeded no danger, she paused not to think!

For she is a mother—her child is a slave—

And she’ll give him his freedom, or find him a grave!

“We Are All Bound Up Together” (11th National Women’s Rights Convention in New York City, 1866)

Source: https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2017/03/21/we-are-all-bound-up-together-may-1866/

“We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul. You tried that in the case of the Negro. You pressed him down for two centuries; and in so doing you crippled the moral strength and paralyzed the spiritual energies of the white men of the country. When the hands of the black were fettered, white men were deprived of the liberty of speech and the freedom of the press . . . This grand and glorious revolution which has commenced, will fail to reach its climax of success, until throughout the length and breadth of the American Republic, the nation shall be so color-blind, as to know no man by the color of his skin or the curl of his hair. It will then have no privileged class, trampling upon outraging the unprivileged classes, but will be then one great privileged nation, whose privilege will be to produce the loftiest manhood and womanhood that humanity can attain.

I do not believe that giving the woman the ballot is immediately going to cure all the ills of life. I do not believer that white women are dew-drops just exhaled from the skies. I think that like men they may be divided into three classes, the good, the bad, and the indifferent. The good would vote according to their convictions and principles; the bad, as dictated by prejudice or malice; and the indifferent will vote on the strongest side of the question, with the winning party . . . You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man’s hand against me. Let me go to-morrow morning and take my seat in one of your street cars — I do not know that they will do it in New York, but they will in Philadelphia — and the conductor will put up his hand and stop the car rather than let me ride.

In advocating the cause of the colored man, since the Dred Scott decision, I have sometimes said I thought the nation had touched bottom. But let me tell you there is a depth of infamy lower than that. It is when the nation, standing upon the threshold of a great peril, reached out its hands to a feebler race, and asked that race to help it, and when the peril was over, said, “You are good enough for soldiers, but not good enough for citizens . . . Talk of giving women the ballot-box? Go on. It is a normal school, and the white women of this country need it. While there exists this brutal element in society which tramples upon the feeble and treads down the weak, I tell you that if there is any class of people who need to be lifted out of their airy nothings and selfishness, it is the white women of America.”

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (1827-1901): A Black Life that Mattered

Source: New York and Slavery: Complicity and Resistance

On July 14, 1854, Elizabeth Jennings and her friend, Sarah Adams, walked to the corner of Pearl and Chatham streets in lower Manhattan. They planned to take a horse-drawn street car along Third Avenue to church. When Jennings tried to enter a street car reserved for whites she was ordered to leave. When she refused, she was physically thrown off the street car.

An account of what happened to Elizabeth was presented on July 17 at a protest meeting at the First Colored Congregational Church in New York City. Elizabeth wrote the statement but did not speak because she was recovering from injuries. Peter Ewell, the meeting’s secretary, read Elizabeth’s testimony to the audience. At the meeting at the First Colored Congregational Church, a Black Legal Rights Association was formed to investigate possible legal action. Elizabeth Jennings decided to sue the street car company. She was represented in court by a young white attorney named Chester A. Arthur, who later became a military officer during the Civil War and a politician. In 1880, Chester A. Arthur was elected Vice-President of the United States and he became president when James Garfield was murdered in 1881.

The court case was successful. The judge instructed the jury that transit companies had to respect the rights all respectable people and the jury awarded Elizabeth Jennings money for damages. While she had asked for $500 in her complaint, some members of the jury resisted granting such a large amount because she was “colored.” In the end, Elizabeth Jennings received $225 plus an additional ten percent for legal expenses.

At the time of this incident, Jennings was a teacher at the African Free School and a church organist. She later started New York City’s first kindergarten for African-American children and operated it from her Manhattan home until her death in 1901.

Documents:

“Outrage upon Colored Persons, “New York Tribune, July 19, 1854, 7:2.

“I (Elizabeth Jennings) held up my hand to the driver and he stopped the cars. We got on the platform, when the conductor told us to wait for the next car. I told him I could not wait, as I was in a hurry to go to church. He then told me that the other car had my people in it, that it was appropriated (intended) for that purpose. I then told him I wished to go to church, as I had been going for the last six months, and I did not wish to be detained.

He insisted upon my getting off the car, but I did not get off. He waited some few minutes, when the driver, becoming impatient, said to me, “Well, you may go in, but remember, if the passengers raise any objections you shall go out, whether or no, or I’ll put you out.” I told him I was a respectable person, born and raised in New York, that I had never been insulted before while going to church, and that he was a good for nothing impudent (rude) fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church. He then said he would put me out.

I told him not to lay his hands on me. I took hold of the window sash and held on. He pulled me until he broke my grasp and I took hold of his coat and held onto that. He ordered the driver to fasten his horses, which he did, and come and help him put me out of the car. They then both seized hold of me by the arms and pulled and dragged me flat down on the bottom of the platform, so that my feet hung one way and my head the other, nearly on the ground. I screamed murder with all my voice, and my companion screamed out “you’ll kill her. Don’t kill her.”

The driver then let go of me and went to his horses. I went again in the car, and the conductor said you shall sweat for this; then told the driver to drive as fast as he could and not to take another passenger in the car; to drive until he saw an officer or a Station House.

They got an officer on the corner of Walker and Bowery, whom the conductor told that his orders from the agent were to admit colored persons if the passengers did not object, but if they did, not to let them ride. When the officer took me there were some eight or ten persons in the car. Then the officer, without listening to anything I had to say, thrust me out, and then pushed me, and tauntingly told me to get redress if I could. I would have come up myself, but am quite sore and stiff from the treatment I received from those monsters in human form yesterday afternoon.”

“A Wholesome Verdict,” New York Tribune, February 23, 1855, 7:4.

“The case of Elizabeth Jennings vs. the Third Ave. Railroad Company, was tried yesterday in the Brooklyn circuit, before Judge Rockwell. The plaintiff is a colored lady, a teacher in one of the public schools, and the organist in one of the churches in this City. She got upon one of the Company’s cars last summer, on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor finally undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full, and when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence. She saw nothing of that, and insisted on her rights. He took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted, they got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress, and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered around, but she effectually (effectively) resisted, and they were not able to get her off. Finally, after the car had gone on further, they got the aid of a policeman, and succeeded in getting her from the car.

Judge Rockwell gave a very clear and able charge, instructing the Jury that the Company were liable for the acts of their agents, whether committed carelessly and negligently, or willfully and maliciously. That they were common carriers, and as such bound to carry all respectable persons; that colored person, if sober, well-behaved, and free from disease, had the same rights as others; and could neither be excluded by any rules of the Company, nor by force or violence; and in case of such expulsion or exclusion, the Company was liable. The plaintiff claimed $500 in her complaint, and a majority of the jury were for giving her the full amount; but others maintained some peculiar notions as to colored people’s rights, and they finally agreed on $225, on which the Court added ten per cent, besides the costs.

Railroads, steamboats, omnibuses, and ferry boats will be admonished from this, as to the rights of respectable colored people. It is high time the rights of this class of citizens were ascertained (respected), and that it should be known whether they are to be thrust from our public conveyances (vehicles), while German or Irish women, with a quarter of mutton or a load of codfish, can be admitted.”

“Legal Rights Vindicated,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, March 2, 1855, 2:5

“Our readers will rejoice with us in the righteous verdict. Miss Elizabeth Jennings, whose courageous conduct in the premises is beyond all praise, comes of a good old New York stock. Her grandfather, Jacob Cartwright, a native African, was a soldier in the Revolutionary War, and took active part in city politics until the time of his death in 1824; her father, Mr. Thomas L. Jennings, was mentioned in our paper as having delivered an oration on the Emancipation of the slaves in this State in 1827, and he was a founder of the New York African Society for Mutual Relief and of other institutions for the benefit and elevation of the colored people. In this suit he has broken new ground, which he proposes to follow up by the formation of a ‘Legal Rights League.’ We hold our New York City gentleman responsible for the carrying out this decision into practice, by putting an end to their exclusion from cars and omnibuses; they must be craven indeed if they fail to follow the lead of a woman.”

Sarah Tompkins Garnet and Susan McKinney Steward: Black Lives that Mattered

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_J._Garnet; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susan_McKinney_Steward

Sarah and Susan Smithwere highly accomplished sisters. Their father, Sylvanus Smith, was one of the founders of the African-American community of Weeksville in Kings County, now Brooklyn, and one of the very few Black Americans eligible to vote in New York when the state still had slavery. Their mother Anne (Springsteel) Smith, was born in Shinnecock in Suffolk County and may have had Native American ancestry.

Sarah Tompkins Garnet (1831-1911)

Sarah Tompkins Garnet was an educator and suffragist and the first female African-American school principal in the New York City public school system. She began teaching at the African Free School of Williamsburg in 1854 and became principal of Grammar School No. 4 in 1863. When she retired in 1900, Garnet had been a teacher and principal for 37 years. Garnet was the founder of the Brooklyn Equal Suffrage League and a leader of the National Association of Colored Women. She married noted abolitionist and minister Henry Highland Garnet in 1879 and they traveled together to Africa. She and her sister Susan McKinney Steward participated in the 1911 Universal Races Congress in London. Public School 9 in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn is named after her.

Susan McKinney Steward (1847-1918)

Susan McKinney Steward was an American physician and author. She was the first African-American woman to earn a medical degree in New York State. Her medical career focused on prenatal care and childhood disease. Between 1870 and 1895, Steward had her own practice in Brooklyn and co-founded the Brooklyn Women’s Homeopathic Hospital and Dispensary. She was also on the board and practiced medicine at the Brooklyn Home for Aged Colored People. Later she was a college physician at Wilberforce University. In 1911, she delivered a paper, “Colored American Women”” at the Universal Race Congress in London.

Documents:

“Mrs. Garnet’s Reception,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 25 June 1907.

“Mrs. Sarah J. S. Garnet, who for many years was the principal of Public School No. 80 and who was an active worker or the retention of Afro-American teachers in the public schools of this state and is now on the retired teachers’ list, gave a reception to New York teachers at her residence, 74 Hancock Street, last evening. There was an excellent program of impromptu speeches varied with music by Professor [Walter] Craig, a pupil of Mrs. Garnet.”

“School to change name in honor of 1st African-American female principal in NYC”

http://brooklyn.news12.com/story/40287636/school-to-change-name-in-honor-of-1st-africanamerican-female-principal-in-nyc

An elementary school in Prospect Heights is changing its name to honor Sarah Smith Garnet, the first African-American female school principal in New York City. P.S. 9 Teunis G Bergen is currently named after a Brooklyn politician in the 1800s who was a slave owner. Parents say the current name sends a bad message. For the past year, parents have discussed changing the name and students got involved. Ninety-three fifth-graders signed a petition for the name change. The new name was decided by a vote. The Department of Education is backing the decision calling Garnet, “a trail-blazing leader who changed our schools and city.” The school’s principal says it is an empowering move for the school, where 40% of the students are black. “It’s important for our children to understand that everyone has a voice and no matter your race, your religion, no matter who you are, you do have a voice and your voice counts,” says principal Sandra D’Avilar.

MARASMUS INFANTUM, By S. S. McKinney, M. D., BROOKLYN, N. Y.

https://archive.org/stream/transactions14yorkgoog/transactions14yorkgoog_djvu.txt

Of the many diseases to which children are victims, marasmus is to me one of the most interesting, from the fact that my success in entering upon and building up a comparatively fair practice is, in a measure, due to the good results I have had in the treatment of this disease. One of my very first cases after graduation was that of a little patient afflicted with this disease, whose parents had become discouraged with the old school treatment, and, as they stated, were willing to give me a trial. The case was a typical one. I put forth my best efforts, supplemented by careful nursing on the part of a loving and intelligent mother, and in time my little patient rounded out into a fine healthy looking child, rewarding my labors in its behalf by being the means of other children being brought to me, similarly afflicted. Thus all along the line up to the present time I find myself being called upon as one able to alleviate the sufferings, if not always able to cure the condition.

The word marasmus is derived from the Greek, meaning ‘I grow lean,’ and is used synonymously with the word atrophy. The name has been fitly chosen for the condition, and indicates a general waste of all the tissues from malnutrition. This disease may develop at any stage of infantile life, and is chiefly the result of the following causes: Unsuitable food, chronic vomiting, chronic diarrhea, worm in the alimentary canal, and more especially inherited syphilis.

The most prominent symptoms are: Emaciation exhaustion, hectic fever, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, dark and shriveled skin, anorexia or great voracity, thirst, sweats, bloated and hard abdomen, enlargement of the glands, great restlessness and nervous irritability, and a host of other symptoms.

In taking charge of a case of this disease, I make it a rule never to promise a cure, but say I will do all I can to restore the little patient to health. I shape my course of treatment to suit each individual case as presented, directing careful attention to the dietary and hygienic needs of the little patients and apply homoeopathic remedies according to their symptomatology.

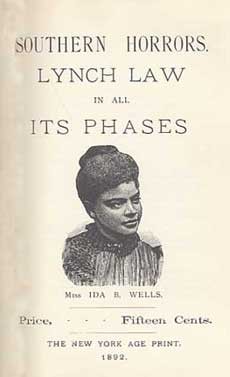

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931): A Black Life that Mattered

Source: https://spartacus-educational.com/FWWwells.htm

In 1901, Ida B. Well published Lynching and the Excuse for It. She argued that the main reasons for lynchings was to intimidate Blacks from demanding their rights and to maintain white power in the South. She was a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909 and headed the organization’s push to make lynching a federal crime. A strong supporter of the right of women to vote, she challenged segregation in the suffrage movement, refusing to march in the back of a march in Washington with a separate black delegation of women. In 1894, Ida B. Wells married Fernand Barnett and they had four children.

Documents:

On Women’s Rights (1886): “I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge.”

Preface to Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892): “The greater part of what is contained in these pages was published in the New York Age June 25, 1892, in explanation of the editorial which the Memphis whites considered sufficiently infamous to justify the destruction of my paper, The Free Speech. Since the appearance of that statement, requests have come from all parts of the country that ‘Exiled,’ (the name under which it then appeared) be issued in pamphlet form . . . It is with no pleasure I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed. Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so. The awful death-roll that Judge Lynch is calling every week is appalling, not only because of the lives it takes, the rank cruelty and outrage to the victims, but because of the prejudice it fosters and the stain it places against the good name of a weak race. The Afro-American is not a bestial race. If this work can contribute in any way toward proving this, and at the same time arouse the conscience of the American people to a demand for justice to every citizen, and punishment by law for the lawless, I shall feel I have done my race a service. Other considerations are of minor importance.”

Letter to President McKinley (1898): “For nearly twenty years lynching crimes have been committed and permitted by this Christian nation. Nowhere in the civilized world save the United States of America do men, possessing all civil and political power, go out in bands of 50 to 5,000 to hunt down, shoot, hang or burn to death a single individual, unarmed and absolutely powerless. Statistics show that nearly 10,000 American citizens have been lynched in the past 20 years. To our appeals for justice the stereotyped reply has been the government could not interfere in a state matter.”

Protest Against the Execution of 12 Black Soldiers (1917): “The result of the court-martial of those who had fired on the police and the citizens of Houston was that twelve of them were condemned to be hanged and the remaining members of that immediate regiment were sentenced to Leavenworth for different terms of imprisonment. The twelve were afterward hanged by the neck until they were dead, and, according to the newspapers, their bodies were thrown into nameless graves. This was done to placate southern hatred. It seemed to me a terrible thing that our government would take the lives of men who had bared their breasts fighting for the defence of our country.”

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Crusade for Justice (1828): “All my life I had known that such conditions were accepted as a matter of course. I found that this rape of helpless Negro girls and women, which began in slavery days, still continued without let or hindrance, check or reproof from the church, state, or press until there had been created this race within a race – and all designated by the inclusive term of ‘colored.’ I also found that what the white man of the South practiced as all right for himself, he assumed to be unthinkable in white women. They could and did fall in love with the pretty mulatto and quadroon girls as well as black ones, but they professed an inability to imagine white women doing the same thing with Negro and mulatto men. Whenever they did so and were found out, the cry of rape was raised, and the lowest element of the white South was turned loose to wreak its fiendish cruelty on those too weak to help themselves. No torture of helpless victims by heathen savages or cruel red Indians ever exceeded the cold-blooded savagery of white devils under lynch law. This was done by white men who controlled all the forces of law and order in their communities and who could have legally punished rapists and murderers, especially black men who had neither political power nor financial strength with which to evade any justly deserved fate. The more I studied the situation, the more I was convinced that the Southerner had never gotten over his resentment that the Negro was no longer his plaything, his servant, and his source of income . . . I’d rather go down in history as one lone Negro who dared to tell the government that it had done a dastardly thing than to save my skin by taking back what I have said. I would consider it an honour to spend whatever years are necessary in prison as the one member of the race who protested, rather than to be with all the 11,999,999 Negroes who didn’t have to go to prison because they kept their mouths shut.”

W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963): A Black Life that Mattered

Source: https://spartacus-educational.com/USAdubois.htm

W.E.B. DuBois was a leading American scholar and civil rights activist at the end of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. He was the first African American to earn a doctorate at Harvard University, a founder of the NAACP in 1909, and editor of its journal, The Crisis.

William Edward Burghardt DuBois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1868. After graduating from high school, he earned a scholarship to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee where he worked as a teacher while attending school. DuBois studied for two years at the University of Berlin and then returned to the United States to complete his education. His Harvard doctoral dissertation on the trans-Atlantic slave trade was later published as a book. His other influential books included The Souls of Black Folk, a biography of John Brown, and Black Reconstruction in America.

As editor of The Crisis, DuBois campaigned against lynchings and Jim Crow laws and for women’s suffrage and equal rights. He also became a socialist, supporting Eugene Debs for President in 1912. His positions brought him into sharp conflict with other African American leaders, particularly Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey.

Starting in the 1930s, DuBois’ views were increasingly aligned with Marxism and its interpretation of race relations in the United States. He supported Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party candidacy for President in 1948, was the party’s candidate for the United States Senate from New York in 1950, and in 1951, during the McCarthy anti-communist witch hunts he was accused of being a Soviet agent and denied a U.S. passport.

In 1961, DuBois joined the Communist Party – USA declaring “Capitalism cannot reform itself. Communism – the effort to give all men what they need and to ask of each the best they can contribute – this is the only way of human life.” DuBois moved to Ghana at the age of 91 where he became a citizen and lived until his death.

Documents:

The Philadelphia Negro (1899): “Such discrimination is morally wrong, politically dangerous, industrially wasteful, and socially silly. It is the duty of the whites to stop it, and to do so primarily for their own sakes. Industrial freedom of opportunity has by long experience been proven to be generally best for all. Moreover the cost of crime and pauperism, the growth of slums, and the pernicious influence of idleness and lewdness, cost the public far more than would the hurt to the feelings of a carpenter to work beside a black man, or a shop girl to start beside a darker mate.”

The Forethought, The Souls of Black Folks (1903): “Herein lie buried many things which if read with patience may show the strange meaning of being black here at the dawning of the Twentieth Century. This meaning is not without interest to you, Gentle Reader; for the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.”

Speech at the Niagara Movement (1906): “We will not be satisfied to take one jot or tittle less than our full manhood rights. We claim for ourselves every single right that belongs to a free-born American, political, civil and social; and until we get these rights we will never cease to protest and assail the ears of America. The battle we wage is not for ourselves alone but for all true Americans.”

The Crisis (1911): “Every argument for Negro suffrage is an argument for women’s suffrage; every argument for women’s suffrage is an argument for Negro suffrage; both are great moments in democracy. There should be on the part of Negroes absolutely no hesitation whenever and wherever responsible human beings are without voice in their government. The man of Negro blood who hesitates to do them justice is false to his race, his ideals and his country.”

Black Reconstruction in America (1935): “The unending tragedy of Reconstruction is the utter inability of the American mind to grasp its real significance, its national and world wide implications . . . This problem involved the very foundations of American democracy, both political and economic.”

The Autobiography of W.E.B. DuBois (1968): “Perhaps the most extraordinary characteristic of current America is the attempt to reduce life to buying and selling. Life is not love unless love is sex and bought and sold. Life is not knowledge save knowledge of technique, of science for destruction. Life is not beauty except beauty for sale. Life is not art unless its price is high and it is sold for profit. All life is production for profit, and for what is profit but for buying and selling again?”

A. Philip Randolph (1889-1979): A Black Life that Mattered

Source: https://spartacus-educational.com/USArandolph.htm

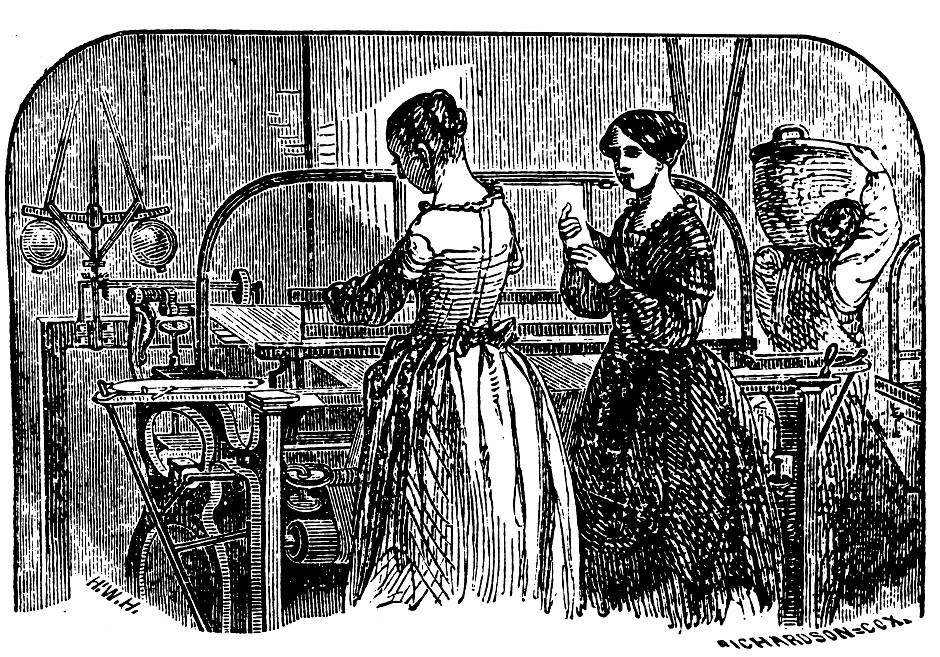

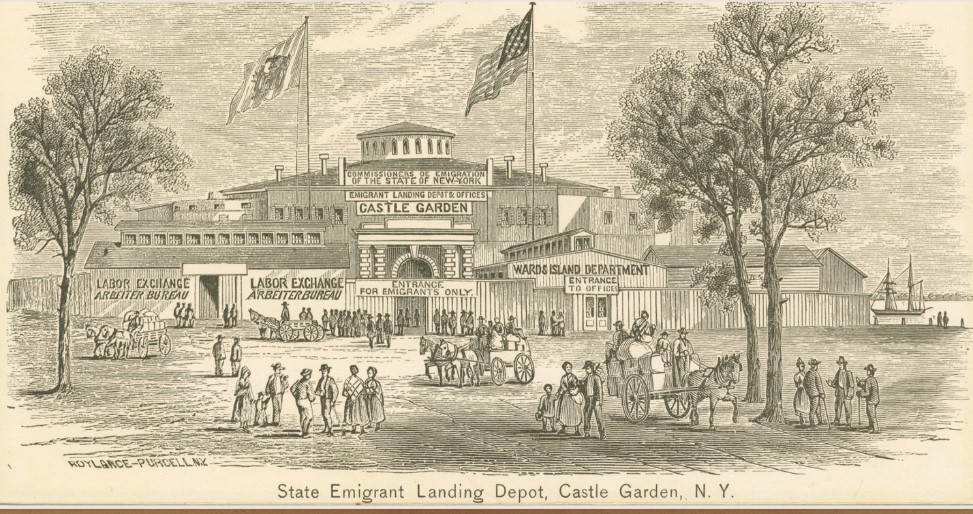

Asa Philip Randolph was born in Florida in 1889. His father was a tailor and an African Methodist Episcopal Church minister. His mother was a seamstress. After high school, Randolph moved north to attend the City College of New York where he studied economics and philosophy, became a socialist, and founded The Messenger, a radical monthly magazine that opposed lynching and U.S. participation in World War I. Randolph was arrested and charged with treason for urging African American men to avoid the military draft but was never prosecuted. As a member of the Socialist Party, Randolph ran a number of unsuccessful campaigns for local office in New York City. During the 1920s, A. Philip Randolph organized Black workers in laundries, clothes factories, and sleeping car porters and in 1929 became president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Documents:

The Messenger, July 1918: “We are fighting ‘to make the world safe for democracy,’ to carry democracy to Germany . . . We are conscripting the Negro into the military and industrial establishments to achieve this end for white democracy four thousand miles away, while the Negro at home, through bearing the burden in every way, is denied economic, political, educational and civil democracy.”

The Messenger, July 1919: “The IWW is the only labor organization in the United States which draws no race or color line. There is another reason why Negroes should join the IWW. The Negro must engage in direct action. He is forced to do this by the Government. When the whites speak of direct action, they are told to use their political power. But with the Negro it is different. He has no political power. Therefore the only recourse the Negro has is industrial action, and since he must combine with those forces which draw no line against him, it is simply logical for him to draw his lot with the Industrial Workers of the World.”

Statement on Proposed March on Washington (January 1941): “Negro America must bring its power and pressure to bear upon the agencies and representatives of the Federal Government to exact their rights in National Defense employment and the armed forces of the country. I suggest that ten thousand Negroes march on Washington, D. C. with the slogan: “We loyal Negro American citizens demand the right to work and fight for our country.” No propaganda could be whipped up and spread to the effect that Negroes seek to hamper defense. No charge could be made that Negroes are attempting to mar national unity. They want to do none of these things. On the contrary, we seek the right to play our part in advancing the cause of national defense and national unity. But certainly there can be no national unity where one tenth of the population are denied their basic rights as American citizens.”

Speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (August 1963): “We are not an organization or a group of organizations. We are not a mob. We are the advance guard of a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom. The revolution reverberates throughout the land, touching every city, every town, every village where blacks are segregated, oppressed and exploited. But this civil rights demonstration is not confined to the Negro; nor is it confined to civil rights; for our white allies knew that they cannot be free while we are not. And we know that we have no future in which six million black and white people are unemployed, and millions more live in poverty. Those who deplore our militancy, who exhort patience in the name of a false peace, are in fact supporting segregation and exploitation. They would have social peace at the expense of social and racial justice. They are more concerned with easing racial tensions than enforcing racial democracy.”

Paul Robeson (1898-1976): A Black Life that Mattered

Paul Robeson was an American social activist, actor, singer, lawyer, and All-American athlete. As an activist, he received global recognition, but in the United States he was persecuted for his radical ideas and suspected communist ties. In August 1949, rioters supported by local law enforcement and the KKK prevented him from performing at a concert in Peekskill, New York. In 1950, his passport was revoked by the United States State Department and in 1956 he was forced to appear at a sub-committee hearing of the House Un-American Activities Committee where he was threatened with indictment for contempt of Congress.

In 1945, Robeson received the NAACP Spingarn medal for outstanding achievement by an African American. In 1978, after his death, he was recognized by the United Nations General Assembly for his efforts challenging apartheid in South Africa. He is a member of the College Football, American Theater, and New Jersey Hall of Fames.

Robeson was born on April 9, 1898, in Princeton, New Jersey. He was the youngest child of Maria Louisa Robeson and Reverend William Robeson, a Presbyterian minister. Reverend Robeson was born enslaved in North Carolina in 1844. In 1901, Reverend Robeson was forced to resign as pastor of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in Princeton because of his outspoken opposition to racial injustice. Paul Robeson credited his commitment to social justice to the way his father was treated.

During World War II, Robeson help rally Americans to support the war effort. In 1940 he broadcast and then recorded Ballad for Americans, a song that defined the United States as an inclusive nation committed to rights for all. Although many considered Robeson the country’s leading entertainer and he continually performed in benefit concerts, he was sometimes prevented from performing or staying in hotels because of racial segregation. In New York City, Robeson performed at the Polo Grounds, the former stadium of the Giants baseball team and at Lewisohn Stadium on the City College campus, both located in Harlem. Among his other interests, Robeson lobbied to desegregate Major League Baseball.

Robeson’s political troubles began at the conclusion of the war. After four African Americans were lynched in July 1946, Robeson met with President Harry Truman. The meeting ended abruptly when Truman declared it was not the right time for a federal anti-lynching law. Robeson responded by founding the American Crusade Against Lynching.

In his testimony before the House Un-American Activities sub-committee, excerpted below from the History Matters website, Paul Robeson accused committee members of being the real Un-Americans and defended fundamental American constitutional rights. James Earl Jones has a narrated version of the testimony available on YouTube.

Document: Testimony of Paul Robeson before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, June 12, 1956

Source: Congress, House, Committee on Un-American Activities, Investigation of the Unauthorized Use of U.S. Passports, 84th Congress, Part 3, June 12, 1956; in Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, Eric Bentley, ed. (New York: Viking Press, 1971), 770.

Part 1: “Are you now a member of the Communist Party?”

RICHARD ARENS (counsel for HUAC and a former aide to Senator McCarthy): Are you now a member of the Communist Party?

PAUL ROBESON: Oh please, please, please.

CONG. GORDON SCHERER (R-OH): Please answer, will you, Mr. Robeson?

PAUL ROBESON: What is the Communist Party? What do you mean by that?

CONG. SCHERER: I ask that you direct the witness to answer the question.

PAUL ROBESON: What do you mean by the Communist Party? As far as I know it is a legal party like the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. Do you mean a party of people who have sacrificed for my people, and for all Americans and workers, that they can live in dignity? Do you mean that party?

ARENS: Are you now a member of the Communist Party?

PAUL ROBESON: Would you like to come to the ballot box when I vote and take out the ballot and see?

ARENS: Mr. Chairman, I respectfully suggest that the witness be ordered and directed to answer that question.

CONG. FRANCIS WALTER, CHAIRMAN (D-PA): You are directed to answer the question.

PAUL ROBESON: I stand upon the Fifth Amendment of the American Constitution.

ARENS: Do you mean you invoke the Fifth Amendment?

PAUL ROBESON: I invoke the Fifth Amendment.

ARENS: Do you honestly apprehend that if you told this Committee truthfully —

PAUL ROBESON: I have no desire to consider anything. I invoke the Fifth Amendment, and it is none of your business what I would like to do, and I invoke the Fifth Amendment . . . [W]herever I have been in the world, Scandinavia, England, and many places, the first to die in the struggle against Fascism were the Communists and I laid many wreaths upon graves of Communists. It is not criminal, and the Fifth Amendment has nothing to do with criminality. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Warren, has been very clear on that in many speeches, that the Fifth Amendment does not have anything to do with the inference of criminality. I invoke the Fifth Amendment.

Part 2: “To whom am I talking?”

PAUL ROBESON: To whom am I talking?

CONG. WALTER: You are speaking to the Chairman of this Committee.

PAUL ROBESON: Mr. Walter?

CONG. WALTER: Yes.

PAUL ROBESON: The Pennsylvania Walter?

CONG. WALTER: That is right.

PAUL ROBESON: Representative of the steelworkers?

CONG. WALTER: That is right.

PAUL ROBESON: Of the coal-mining workers and not United States Steel, by any chance? A great patriot.

CONG. WALTER: That is right.

PAUL ROBESON: You are the author of all of the bills that are going to keep all kinds of decent people out of the country.

CONG. WALTER: No, only your kind.

PAUL ROBESON: Colored people like myself, from the West Indies and all kinds. And just the Teutonic Anglo-Saxon stock that you would let come in.

CONG. WALTER: We are trying to make it easier to get rid of your kind, too.

PAUL ROBESON: You do not want any colored people to come in?

Part 3: “The reason I am here today”

PAUL ROBESON: Could I say that the reason that I am here today, you know, from the mouth of the State Department itself, is: I should not be allowed to travel because I have struggled for years for the independence of the colonial peoples of Africa. For many years I have so labored and I can say modestly that my name is very much honored all over Africa, in my struggles for their independence . . . The other reason that I am here today, again from the State Department and from the court record of the court of appeals, is that when I am abroad I speak out against the injustices against the Negro people of this land. I sent a message to the Bandung Conference and so forth. That is why I am here. This is the basis, and I am not being tried for whether I am a Communist, I am being tried for fighting for the rights of my people, who are still second-class citizens in this United States of America. My mother was born in your state, Mr. Walter, and my mother was a Quaker, and my ancestors in the time of Washington baked bread for George Washington’s troops when they crossed the Delaware, and my own father was a slave. I stand here struggling for the rights of my people to be full citizens in this country. And they are not. They are not in Mississippi. And they are not in Montgomery, Alabama. And they are not in Washington. They are nowhere, and that is why I am here today. You want to shut up every Negro who has the courage to stand up and fight for the rights of his people, for the rights of workers, and I have been on many a picket line for the steelworkers too. And that is why I am here today.”

Part 4: “I belong to the American resistance movement.”

PAUL ROBESON: Would you please let me read my statement at some point?

CONG. WALTER: We will consider your statement.

ARENS: I do not hesitate one second to state clearly and unmistakably: I belong to the American resistance movement which fights against American imperialism, just as the resistance movement fought against Hitler.

PAUL ROBESON: Just like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman were underground railroaders, and fighting for our freedom, you bet your life . . . Four hundred million in India, and millions everywhere, have told you, precisely, that the colored people are not going to die for anybody: they are going to die for their independence. We are dealing not with fifteen million colored people, we are dealing with hundreds of millions.

Part 5: “My people died to build this country.”

PAUL ROBESON: In Russia I felt for the first time like a full human being. No color prejudice like in Mississippi, no color prejudice like in Washington. It was the first time I felt like a human being. Where I did not feel the pressure of color as I feel [it] in this Committee today.

CONG. SCHERER: Why do you not stay in Russia?

PAUL ROBESON: Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear? I am for peace with the Soviet Union, and I am for peace with China, and I am not for peace or friendship with the Fascist Franco, and I am not for peace with Fascist Nazi Germans. I am for peace with decent people.

CONG. SCHERER: You are here because you are promoting the Communist cause.

PAUL ROBESON: I am here because I am opposing the neo-Fascist cause which I see arising in these committees. You are like the Alien [and] Sedition Act, and Jefferson could be sitting here, and Frederick Douglass could be sitting here, and Eugene Debs could be here . . .[Y]ou gentlemen belong with the Alien and Sedition Acts, and you are the non-patriots, and you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves.

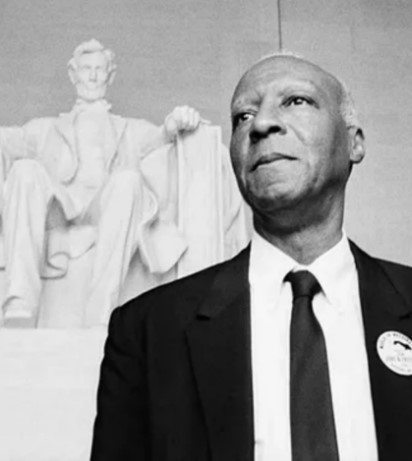

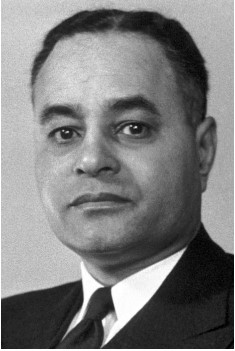

Ralph Bunche (1904-1971): A Black Life that Mattered

Documents:

Segregation in Los Angeles (1926)

“I hope that the future generations of our race rise as one to combat this vicious habit at every opportunity until it is completely broken down. I want to tell you that when I think of such outrageous atrocities as this latest swimming pool incident, which has been perpetrated upon Los Angeles Negroes, my blood boils. And when I see my people so foolhardy as to patronize such a place, and thus give it their sanction, my disgust is trebled. Any Los Angeles Negro who would go bathing in that dirty hole with that sign—‘For Colored Only,’ gawking down at him in insolent mockery of his Race, is either a fool or a traitor to his kind.”

Some Reflections on Peace in Our Time (1950)

“In this most anxious period of human history, the subject of peace, above every other, commands the solemn attention of all men of reason and goodwill. Moreover, on this particular occasion, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Nobel Foundation, it is eminently fitting to speak of peace. No subject could be closer to my own heart, since I have the honour to speak as a member of the international Secretariat of the United Nations. In these critical times – times which test to the utmost the good sense, the forbearance, and the morality of every peace-loving people – it is not easy to speak of peace with either conviction or reassurance. True it is that statesmen the world over, exalting lofty concepts and noble ideals, pay homage to peace and freedom in a perpetual torrent of eloquent phrases. But the statesmen also speak darkly of the lurking threat of war; and the preparations for war ever intensify, while strife flares or threatens in many localities.

The words used by statesmen in our day no longer have a common meaning. Perhaps they never had. Freedom, democracy, human rights, international morality, peace itself, mean different things to different men. Words, in a constant flow of propaganda – itself an instrument of war – are employed to confuse, mislead, and debase the common man. Democracy is prostituted to dignify enslavement; freedom and equality are held good for some men but withheld from others by and in allegedly “democratic” societies; in “free” societies, so-called, individual human rights are severely denied; aggressive adventures are launched under the guise of “liberation”. Truth and morality are subverted by propaganda, on the cynical assumption that truth is whatever propaganda can induce people to believe. Truth and morality, therefore, become gravely weakened as defences against injustice and war. With what great insight did Voltaire, hating war enormously, declare: ‘War is the greatest of all crimes; and yet there is no aggressor who does not colour his crime with the pretext of justice’.”

Racial Prejudice in America (1954)

“The existence of racial prejudice, the practice of racial or religious bigotry in our midst today, should be the active concern of every American who believes in our democratic way of life. Such attitudes and practices subvert the foundation principles of our society. They are more costly and more dangerous today than ever before in our history. Indeed, it is impossible to calculate the tremendous costs to the nation of such attitudes and their shameful manifestations. They are a seriously divisive influence amongst our people. They create resentment, unrest and disturbances in our communities. They deprive us of our maximum national unity at a time when our way of life and all that we stand for is gravely threatened from without. They prevent us from using a substantial part of our manpower effectively, even though we are seriously short of manpower, to meet the challenge confronting us from an external world.”

Letter to 4th graders (1964)

“The habit of always looking on the bright side of things may make one appear naive now and then, but in my experience it is the best antidote for worry and ulcers. I am often called an optimist. No doubt I am; but if so, it is by training rather than by nature – my mother’s training. I am convinced that nothing is ever finally lost until faith and hope and dreams are abandoned, and then everything is lost. This, I feel, is what my mother meant.”

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977): A Black Life that Mattered

Fannie Lou Townsend’s parents were sharecroppers on the Marlow Plantation in the Mississippi River delta region of Sunflower County, Mississippi. Fannie Lou was the youngest of her parent’s twenty children. As a child, Hamer helped her family pick cotton and grow corn. She was only able to attend school until sixth grade. In 1945, Fannie Lou married Perry Hamer, a tractor driver and sharecropper on the Marlow plantation. The couple never had children.

In 1961, Hamer had a hysterectomy and was sterilized without her consent. It is suspected this was part of a plan by the State of Mississippi to reduce the number of poor blacks in the state.

In 1962, after participating in a bus trip organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to register African-Americans voters, Fanny Lou Hamer was recruited to work for that organization. Her demand to vote led to threats on her life and the lives of family members and she was forced to move away to protect them.

In June 1963, Fanny Lou Hamer was arrested on a false charge and severely beaten by police in Winona, Mississippi. In 1964, she helped found and was elected vice-chair of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. On August 22, 1964, Hamer addressed the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey where she challenged Mississippi’s all-white and anti-civil rights delegation. Hamer ran for Congress in 1964 and 1965, and in 1968 was a member of Mississippi’s official delegation to the Democratic National Convention. She died of heart failure in 1977.

This biography of Fannie Lou Hamer is drawn from a number of online sources including Timeline, Wikipedia, and American Public Media. It concludes with excerpts from her testimony at the 1964 Democratic Party presidential nominating convention and a speech she delivered in Harlem, New York in December 1964.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fannie_Lou_Hamer

https://timeline.com/hamer-speech-voting-rights-d5f6ddc7470a

Documents:

Fannie Lou Hamer testifies before the Credentials Committee of the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey (August 22, 1964)

http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/flhamer.html

“My name is Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, and I live at 626 East Lafayette Street, Ruleville, Mississippi, Sunflower County, the home of Senator James O. Eastland, and Senator Stennis. It was the 31st of August in 1962 that eighteen of us traveled twenty-six miles to the county courthouse in Indianola to try to register to become first-class citizens. We were met in Indianola by policemen, Highway Patrolmen, and they only allowed two of us in to take the literacy test at the time. After we had taken this test and started back to Ruleville, we were held up by the City Police and the State Highway Patrolmen and carried back to Indianola where the bus driver was charged that day with driving a bus the wrong color.

After we paid the fine among us, we continued on to Ruleville, and Reverend Jeff Sunny carried me four miles in the rural area where I had worked as a timekeeper and sharecropper for eighteen years. I was met there by my children, who told me that the plantation owner was angry because I had gone down to try to register. After they told me, my husband came, and said the plantation owner was raising Cain because I had tried to register. Before he quit talking the plantation owner came and said, “Fannie Lou, do you know – did Pap tell you what I said?” And I said, “Yes, sir.” He said, “Well I mean that.” He said, “If you don’t go down and withdraw your registration, you will have to leave” . . . And I addressed him and told him and said, “I didn’t try to register for you. I tried to register for myself.” I had to leave that same night.

June the 9th, 1963, I had attended a voter registration workshop; was returning back to Mississippi. Ten of us was traveling by the Continental Trailway bus. When we got to Winona, Mississippi . . . I stepped off of the bus to see what was happening and somebody screamed from the car that the five workers were in and said, “Get that one there.” When I went to get in the car, when the man told me I was under arrest, he kicked me. I was carried to the county jail . . . And it wasn’t too long before three white men came to my cell . . . I was carried out of that cell into another cell where they had two Negro prisoners. The State Highway Patrolmen ordered the first Negro to take the blackjack. The first Negro prisoner ordered me, by orders from the State Highway Patrolman, for me to lay down on a bunk bed on my face. I laid on my face and the first Negro began to beat. I was beat by the first Negro until he was exhausted. I was holding my hands behind me at that time on my left side, because I suffered from polio when I was six years old. After the first Negro had beat until he was exhausted, the State Highway Patrolman ordered the second Negro to take the blackjack . . . Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

“I’m Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired,” Harlem, New York (Dec. 20, 1964)

https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2019/08/09/im-sick-and-tired-of-being-sick-and-tired-dec-20-1964/

“For three hundred years, we’ve given them time. And I’ve been tired so long, now I am sick and tired of being sick and tired, and we want a change. We want a change in this society in America because, you see, we can no longer ignore the facts and getting our children to sing, “Oh say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, what so proudly we hailed.” What do we have to hail here? The truth is the only thing going to free us. And you know this whole society is sick . . . But this is something we going to have to learn to do and quit saying that we are free in America when I know we are not free. You are not free in Harlem. The people are not free in Chicago, because I’ve been there, too. They are not free in Philadelphia, because I’ve been there, too. And when you get it over with all the way around, some of the places is a Mississippi in disguise. And we want a change. And we hope you support us in this challenge.”