New Jersey Council for the Social Studies

Engaging High School Students in Global Civic Education Lessons in U.S. History

The relationship between the individual and the state is present in every country, society, and civilization. Relevant questions about individual liberty, civic engagement, government authority, equality and justice, and protection are important for every demographic group in the population. In your teaching of World History, consider the examples and questions provided below that should be familiar to students in the history of the United States with application to the experiences of others around the world.

These civic activities are designed to present civics in a global context as civic education happens in every country. The design is flexible regarding using one of the activities, allowing students to explore multiple activities in groups, and as a lesson for a substitute teacher. The lessons are free, although a donation to the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies is greatly appreciated. www.njcss.org

Era 8 The Twenties (1920–1930)

The Twenties were the first time that more Americans lived in cities than on farms. It was a decade of social, economic and political change following the devastating effects of World War I, the mass production of the automobile, and the radio brought news, sports, and entertainment into the homes of people. The way people understood information was changing as newspapers and advertisements supported a “consumer culture.” It was also a time when many people were uncomfortable with the secular lifestyle and attitudes rejected alcohol, even though it was the fifth largest industry in the country and restrictive laws were passed regarding immigration as the country favored isolationist policies.

Activity #1: The Scopes Trial (1925) and the National School System in Kenya (2024)

Education in the United States is under the control of local communities and each of the 50 states. The federal government tries to influence education with financial assistance and has authority to enforce national laws that apply to civil and human rights. In 1923, Tennessee became the first state to ban the teaching of evolution. Tennessee had the legal authority to determine the content of the curriculum in public schools. The legal issues would test the freedom of speech for teachers and the right of the state to respect the views of many citizens and state legislators, regarding their understanding of the Holy Bible.

Fundamentalism represented the literal interpretation of the Holy Bible and had been gaining popularity in American culture for 40 years before the Scopes Trial. The philosophy of communism in the Soviet Union opposed the freedom of religious expression and the unprecedented death in World War I prompted many to question the existence of God. It was also a time of spiritual evangelism when people used the teachings of the Holy Bible to counter the modern ideas of jazz music, sexual promiscuity, and secularism.

The jury found Scopes guilty of violating the law and fined him $100. Bryan and the anti-evolutionists claimed victory, and the Tennessee law would stand for another 42 years. The ACLU publicized scientific evidence for evolution. The verdict did have a chilling effect on teaching evolution in the classroom, however, and not until the 1960s did it reappear in schoolbooks. It continues as an issue in some states today.

The National School System in Kenya

Kenya has an educational system that is considered one of the best in the world. Education is controlled by the government and changes take time to make. Recently, Kenya made significant changes in the curriculum with a vision to make Kenya a leader in Africa by 2063, the next 40 years. “The overall aim of the new curriculum is to equip citizens with skills for the 21st century and hinges on the global shift towards education programs that encourage optimal human capital development. Education should be viewed in a holistic spectrum that includes schooling and the co-curriculum activities that nurture, mentor, and mold the child into productive citizens.”

There are advantages and disadvantages to both a national and federal system of education. Canada, Australia, and Germany have federal systems of education that might be compared to the United States. The majority of countries in the world have a national system similar to the one in Kenya. U.S. News & World Report published a study of the education in 87 countries. For discussion, consider if the goal of a well-developed educational system is to prepare students for higher education, support employment, educate citizens, teach values, access, efficiency of costs, etc. Another area for discussion could be if the purpose of education is the focus on the well-being and development of the individual or if the emphasis is on subject matter content.

Questions:

- Who should decide matters of content in the curriculum?

- Should parents have the authority to ‘opt out’ of lessons?

- Should teachers or assessments determine what is taught?

- What is the purpose of education?

- Is the primary purpose of education to teach skills, content, or to prepare children to be citizens?

- Should the U.S. government limit or empower the U.S. Department of Education in the area of curriculum?

The Scopes Trial (National Constitution Center)

The Scopes Trial (History Channel)

The Scopes Trial (Bill of Rights Institute)

Activity #2: Death of President Harding (1923) and Death of Vladimir Lenin (1924): The transfer of political power

On the evening of the president’s death, Herbert Hoover sent out the official news that the president had died of “a stroke of cerebral apoplexy.” But it was most likely a heart attack, that ended Harding’s life at the age of 58, two years more than the average life span for an American male in 1923 (56.1 years).

President Harding’s Vice President was Calvin Coolidge. He was from Massachusetts and at the time of Harding’s death he was visiting his family at their home in Plymouth, Vermont. He issued the following statement:

“Reports have reached me, which I fear are correct, that President Harding is gone. The world has lost a great and good man. I mourn his loss. He was my chief and my friend.

It will be my purpose to carry out the policies which he has begun for the service of the American people and for meeting their responsibilities wherever they may arise. For this purpose I shall seek the cooperation of all those who have been associated with the President during his term of office. Those who have given their efforts to assist him I wish to remain in office that they may assist me. I have faith that God will direct the destinies of our nation.

It is my intention to remain here until I can secure the correct form for the oath of office, which will be administered to me by my father, who is a notary public, if that will meet the necessary requirement. I expect to leave for Washington during the day.”

CALVIN COOLIDGE

Calvin Coolidge’s father was a notary public and administered the Oath of office at 2:47 a.m. in the middle of the night in his home. President Coolidge addressed Congress for the first time when it returned to Washington D.C. on December 6, 1923, expressing support for many of Harding’s policies and he continued with most of Harding’s advisors. The transfer of political power was orderly.

The Death of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin died at age 58 on January 21, 1924, less than six months after President Harding. He had suffered from three strokes and his death was expected. Lenin did not name a successor and the transition to power was contentious between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky.

Alexsei Rykov and V.M Molotov were technically the leaders of the Soviet Union. Joseph Stalin was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and Leon Trotsky was the Minister of War. As party secretary Stalin controlled appointees and used the position to install people loyal to him. Trotsky represented the faction that favored the spread of socialism in a world revolution. He believed this was necessary for the Soviet Union to develop a stronger economy. In contrast, Stalin did not see a world revolution as probable and favored the gradual economic development through a series of five-year plans with quotas and state ownership of land. Leon Trotsky was exiled to Mexico in 1928 and Josef Stalin became the de facto leader of the Soviet Union.

Questions:

- Is it likely that the death of an American president in this decade would result in an orderly transfer of power or would it be contentious between leaders within the Democratic and Republican Party?

- Should the successor of an American president be expected to continue with the appointed advisors and policies of the Administration, or should the new president be encouraged to develop policies consistent with his or her political views?

- Is Russia at risk of a contentious transition to a new government in the event of the unexpected death of Vladimir Putin?

- Is a parliamentary system of government more effective and efficient in the transfer of political power than the government of the United States, Russia, or China?

Activity #3: Palmer Raids and the OGPU in the Soviet Union

How does a government protect the equality and presumed innocence of individual citizens and also protect the general welfare and safety of the public? On May 1, 1919 (May Day), postal officials discovered 20 bombs in the mail of prominent capitalists, including John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan, Jr., as well as government officials like Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. A month later, bombs exploded in eight American cities. In 1919 and 1920, President Wilson’s attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, led raids on the Communist Party and the International Workers of the World.

In November 1919, Palmer ordered government raids that resulted in the arrests of 250 suspected radicals in 11 cities. The Palmer Raids reached their height on January 2, 1920, when government agents made raids in 33 cities. More than 4,000 alleged communists were arrested and jailed and 556 immigrants were deported.

OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate) in the Soviet Union

The secret police in the Soviet Union is sometimes called or associated with the Checka, Red Terror, Gulag, KGB, or state police. The Bolsheviks formed the Cheka when Vladimir Lenin was wounded in an assassination attempt in 1918. After the October Revolution in 1917, Russia was in a civil war. The OGPU was commissioned in November 15, 1923 and conducted mass shootings and hangings without trials. It is estimated that the revolutionary tribunals executed 100,000. The tribunals sanctioned purges of everyone including Russia’s imperial family, land-owning peasants, journalists, priests, scholars, and the homeless.

The operations of the OGPU reflected decisions of the Party leadership. It was directed to check on church activities, foreigners, and members of opposition parties. It supervised kept a watchful eye on the morale, loyalty, and efficiency or workers.

Questions:

- Do governments have a responsibility to secretly observe the activities of any of its people?

- How can a government responsibly protect its citizens from terrorist or subversive activities?

- Is the suspension of habeas corpus and individual liberties justified in times of war or civil unrest?

- In the United States does the federal government (President) have the authority to send the National Guard or armed forces into a city or state without the approval of the governor or state government?

Palmer Raids (Chronicling America)

The Red Scare (Digital History)

Bombing on Wall Street (You Tube, American Experience, PBS)

Authority of the President to Use the National Guard and Army to Control the Border (CRS)

Establishment of the OGPU (November 15, 1923)

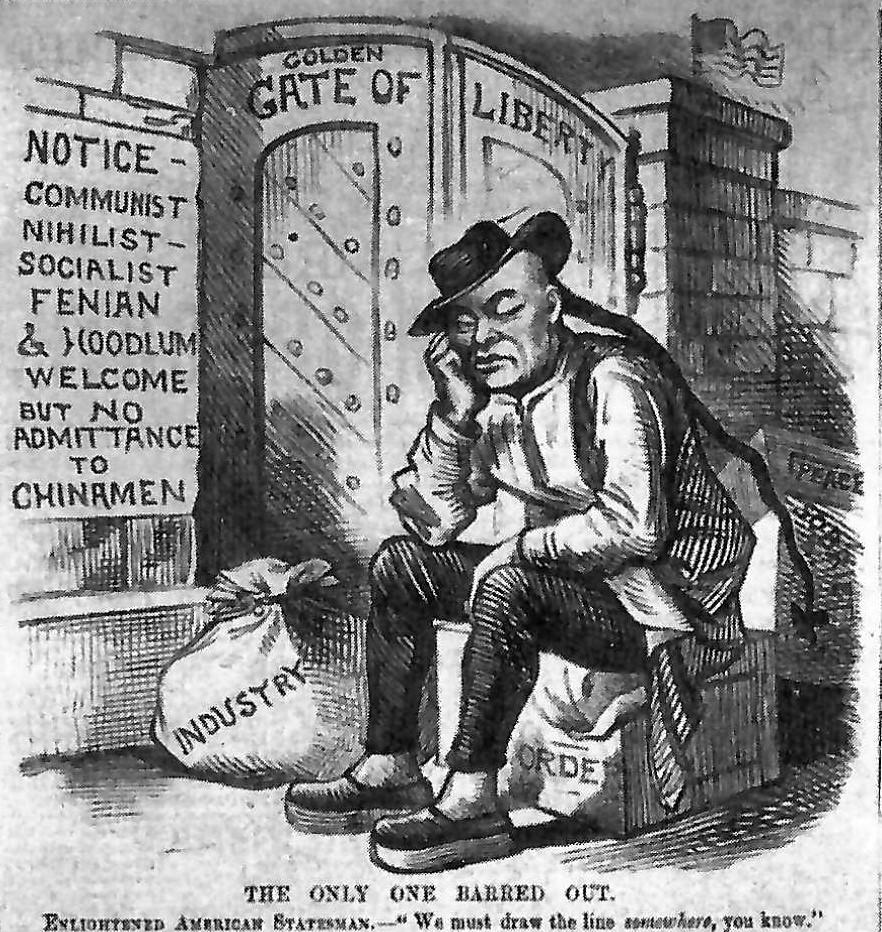

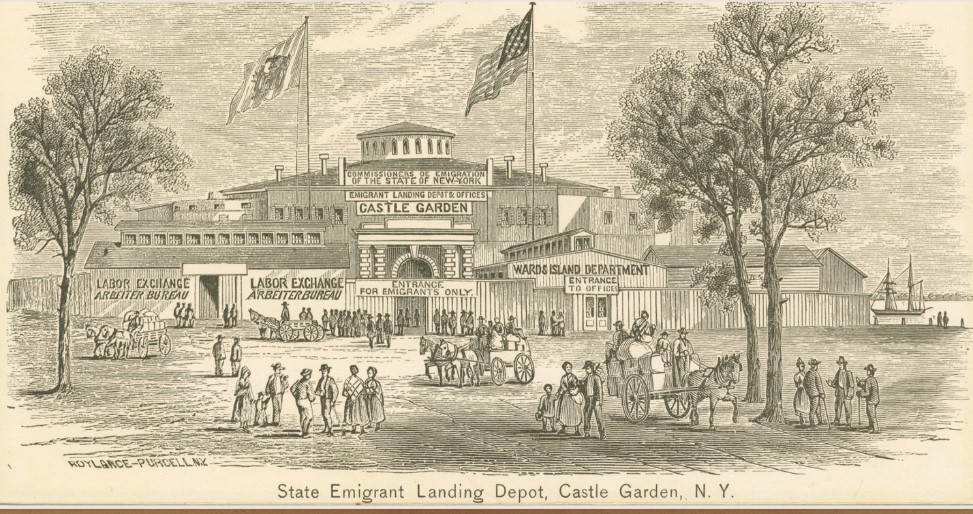

Activity #4: The Immigration Debate in the United States and Lithuania

Immigration in the United States

In 1965, the United States passed the Immigration and Nationality Act ending all quotas based on national origin and replacing them with a system of preferences based on family relations to US residents and labor qualifications. Total immigration was limited to 170,000 annually for the Eastern Hemisphere; and 120,000 for the Americas. The flow of immigrants to the southern border of the United States has exceeded this number for decades. It is now almost one million a year, with about 40% of this number coming from Central America and Mexico. It is also difficult to hire border patrol officers to process the requests for asylum and legal entry. The population of the United States is declining and immigration is the reason for the small increase. Immigrants also fill needed jobs. Most of the migrant population is living in six states.

Immigration in Lithuania

In 2021, political tensions between Lithuania and Belarus flared, precipitating a crisis at the borders during which more than 4 000 migrants largely from the Middle East and South Asia were stranded facing inadequate food, water, clothing, or shelter. Lithuania is a country of about 4 million people and the government did not welcome the surge of immigrants The Lithuanian Red Cross provided humanitarian assistance in the form of non-food items, medicine, and food, as well as mental health care. Since 2021, Lithuanian border guards have prevented around 20,000 people from crossing the border from Belarus. They check the documents of each individual and have permitted asylum seekers to enter.

“The protection of the right to life and the prohibition of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment provide the cornerstones of any human rights compliant response to border crossing and must be fully upheld at all times, including in emergency situations. I have received consistent worrying reports of patterns of violence and other human rights violations committed against migrants, including in the context of pushbacks at Lithuania’s border with Belarus. Parliament should contribute to putting a stop to these human rights violations and take the lead in guaranteeing a human rights compliant migration policy.” (European Union Commissioner on Human Rights, 2023)

The Lithuanian parliament adopted a law on Tuesday (25 April, 2023) legalizing the turning away of irregular migrants at the border under a state-level extreme situation regime or a state of emergency.

Questions:

- Do nations have the right to stop people from entering their country or does the need to provide humanitarian care take precedence?

- Many countries are facing large numbers of immigrants for economic and political reasons. How can countries manage this population movement?

- How would you define a humanitarian immigration policy?

- Which countries have the most humane and effective immigration policies?

https://www.cgdev.org/blog/which-countries-have-best-migration-policies