Lyddie the Mill Girl – An Interdisciplinary 7th Grade Unit

Natalie Casale, Dena Giacobbe, Amanda Nardo, and Jamie Thomas

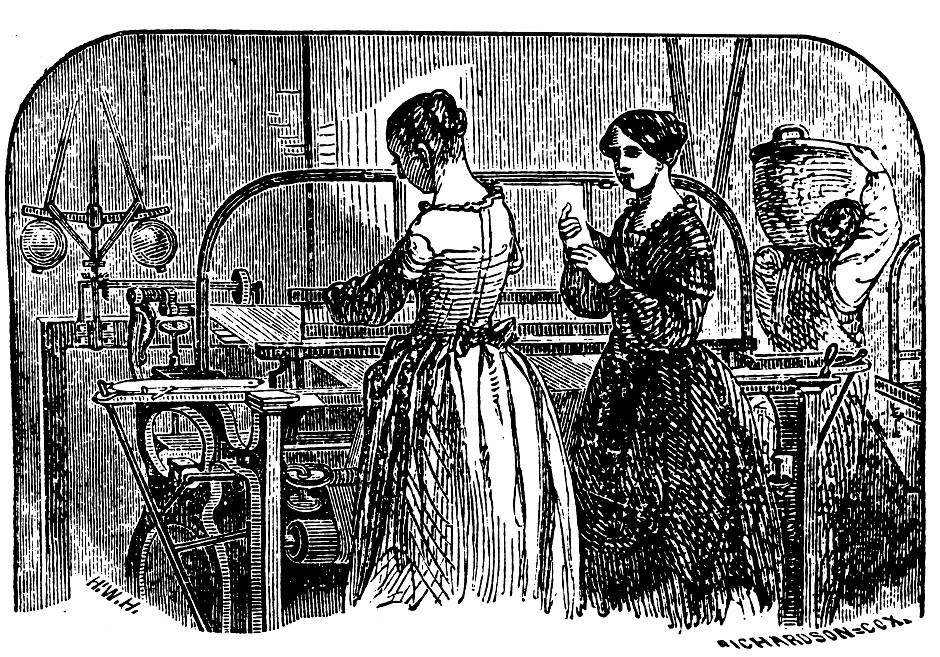

In these lessons, we will look back to the 19th century where workers were not protected and oftentimes had to work in awful conditions, like the young women who worked in the mills in Lowell, Massachusetts. These young women, known as mill girls, worked long hours and were often hurt by the machinery. If they were lucky enough to escape getting hurt by the machines, after working in the mills for a couple of years, the girls started to have respiratory health problems. The novel Lyddie is about a young girl who worked in the Lowell mills. By reading the book, the students have learned about what a typical day is like working at the mills and have read about Lyddie and her friends enduring horrible working conditions and getting hurt as a result. This lesson will explore what the conditions were like working in the mills in the 19th century. Students will examine a picture of a mill girl working the machinery and recall the effects the mills had on Lyddie and her friends. The students will then read about the Lowell mills and about one mill girl’s life, Sarah Bagley. Students will compare and contrast Lyddie and Bagley’s experiences in the mills. By the end of the lesson, the students will be able to describe what it is like to work in the mills and recommend what future mill girls should keep in mind when working in the mills. The students will be grouped homogeneously, working with partners throughout the lesson.

(A) Sarah George Bagley

Source: https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/historyculture/sarah-bagley.htm

https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/historyculture/the-mill-girls-of-lowell.htm

(A) Sarah George Bagley

Source: https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/historyculture/sarah-bagley.htm

Sarah George Bagley was born April 19, 1806 to Nathan and Rhoda Witham Bagley. Raised in rural Candia, New Hampshire, she came to the booming industrial city of Lowell in 1837 at the age of 31, where she began work as a weaver at the Hamilton Manufacturing Company. Though older than many of the Yankee women who flocked to Lowell’s mills, Bagley shared with them the shift from rural family life to the urban industrial sphere. While working in the Lowell mills, Sarah Bagley’s view of the world around her changed radically. While much of her life remains surrounded by questions, the record of Bagley’s experiences as a worker and activist in Lowell, Massachusetts, reveals a remarkable spirit. Condemned by some as a rabble rouser and enemy of social order, many have celebrated her as a woman who fought against the confines of patriarchal industrial society on behalf of all her sisters in work and struggle.

“Let no one suppose the ‘factory girls’ are without guardian. We are placed in the care of overseers who feel under moral obligation to look after our interests.” – Sarah Bagley, 1840

“I am sick at heart when I look into the social world and see woman so willingly made a dupe to the beastly selfishness of man.” – Sarah Bagley, 1847

While many found a sense of independence in coming to the city and earning a wage for the first time, the presence of paternalistic capitalism ensured that working women would never be “without guardian;” or as Bagley would later assert, that factory women would never experience true freedom. Bagley was initially inclined to accept the prescribed order in the Spindle City—she became an excellent weaver and began to write for the Lowell Offering, a literary magazine written by mill workers but overseen and partly funded by the mill corporations. Bagley’s 1840 essay entitled “The Pleasures of Factory Work,” which argued that cotton mill labor was congenial to “pleasurable contemplation” and other noble pursuits, was representative of the positive, proper image of the mills presented in the pages of the Offering.

Was it deteriorating conditions in the cotton factories or some internal shift in Sarah Bagley’s worldview that precipitated her transformation from “mill girl” to ground-breaking labor activist in the span of only a few short years? By 1840 the exploitation of Lowell mill workers was becoming increasingly apparent: the frequent speedups and constant pressure to produce more cloth drove Bagley from the weave room into the cleaner, more relenting dressing room. Here she oversaw the starching (or “dressing”) of the warp threads that constitute the framework for woven cloth.

By 1842 the pressures that Bagley had experienced as a weaver began to erupt in the form of labor conflict. In that year the Middlesex Manufacturing Company, one of Lowell’s textile giants, announced a speedup and subsequent 20% pay cut. In protest, seventy female workers walked out. All were fired and blacklisted. Lowell’s industrial capitalists made it very clear that they would not tolerate challenges to their authority, especially not by young female workers.

The walkout of 1842 did not instantly convert Sarah Bagley into a labor activist; several months after the unsuccessful strike by the Middlesex weavers, Bagley returned to weaving, this time as an employee of the Middlesex mills.

A radical change in Sarah’s own views of the world around her, however, was not far off. How exactly she became involved with the labor movement is uncertain. In 1844, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association (LFLRA) was founded, becoming one of the earliest successful organizations of working women in the United States, with Sarah Bagley as its president. Working in cooperation with the New England Workingmen’s Association (NEWA) and spurred by a recent extension of work hours, the organizations submitted petitions totaling 2,139 names to the Massachusetts state legislature in 1845. These petitions demanded the reduction of the workday to ten hours on behalf workers’ health as well as their “intellectual, moral and religious habits.” In response, the legislature called a hearing and asked Bagley, among eight others, to testify. Despite the efforts of Bagley and her colleagues, the legislators ultimately refused to act against the powerful mills.

While advocating for the ten-hour workday and against corporate abuses remained the cornerstones of the LFLRA’s activism under Bagley’s presidency, women’s rights issues quickly assumed a prominent role as well. Speaking at the first New England Workingmen’s Association convention at a time when public speaking represented a radical departure from acceptable feminine behavior, Bagley called on male workers to exercise their right to vote on behalf of female workers who lacked political representation.

The year 1845 also saw Sarah taking on new responsibilities as a writer and editor for the Voice of Industry, founded in 1844 by the New England Workingmen’s Association. In a July Fourth speech, Bagley—just named one of the NEWA’s five new vice presidents—condemned the Lowell Offering and its editor Harriet Farley as “a mouthpiece of the corporations,” voicing a deep transformation of her own views. The ensuing public feud belied Bagley’s own praise of the mill companies published in the Offering only five years prior.

1846 was a busy year for Bagley and the Female Labor Reform Association, as she and several associates traveled throughout New England recruiting workers and organizing chapters of the FLRA and the NEWA. She also served as a delegate to numerous labor conventions and associated with a wide variety of progressives beyond the immediate labor movement, from abolitionists to prison reformers. Having left mill work in early 1846, Bagley now considered labor reform her primary calling. 1846 also saw an increase in the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association’s activities, mounting a campaign against yet another speedup and piece rate reduction, establishing a lecture series for workers, and penning pamphlets exposing the contradictions of mill owner paternalism and decrying the “ignorance, misery, and premature decay of both body and intellect” caused by mill work.

These achievements, however, were tempered by continued frustration on the ten-hour front. A second petition, this time numbering 4,500 signatures, was submitted to the legislature and rejected. Perhaps in part owing to the lack of success in attaining this goal, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association began to shift its focus away from the militant labor activism espoused by Sarah Bagley. Around this time Bagley also came into conflict with the Voice of Industry’s new editor, John Allen, over the role of women in the newspaper’s production. In October of 1846 Bagley published her last piece in the Voice of Industry; in early 1847 she left the Female Labor Reform and Mutual Aid Society (formerly LFLRA) after three brief but influential years of radical activism.

Sarah Bagley once again defied expectations and gendered boundaries in the latter half of 1846 when she took a job as the nation’s first female telegraph operator, first in Lowell and then in Springfield, Massachusetts. Local newspapers were skeptical of both this new technology and of the ability of a woman to fill the position of telegraph depot superintendent—one paper mused, “Can a woman keep a secret?” However, Bagley proved well-suited to this work and through her example opened the new occupational field of telegraphy to women around the country.

Bagley remained employed at the telegraph depot until 1848, when Hamilton mill records show her mysteriously returning to work in the weave room for five months. Bagley had been out of the mills for two years; it must have been a melancholy return for the woman who had risen to fame as an activist against the corporations that she now for whatever reason had to rely upon once again. In September of 1848 she left Lowell to care for her sick father and never returned. At this point Bagley’s life lapses again into partial obscurity—some report that she moved to Philadelphia and worked as a social reformer before marrying and moving to upstate New York to practice homeopathic medicine. While there is some evidence to support this story, others have asserted that she in fact dropped completely from the historical record after 1848. Her date of death is unknown.

(B) The Lowell Mill Girls Go on Strike (1836)

by Harriet Hanson Robinson

Source: Harriet Hanson Robinson, Loom and Spindle or Life Among the Early Mill Girls (New York, T. Y. Crowell, 1898), 83–86. http://hti.osu.edu/sites/hti.osu.edu/files/Harriet-Robinson-account.pdf

A group of Boston capitalists built a major textile manufacturing center in Lowell, Massachusetts, in the second quarter of the 19th century. The first factories recruited women from rural New England as their labor force. These young women, far from home, lived in rows of boardinghouses adjacent to the growing number of mills. The industrial production of textiles was highly profitable, and the number of factories in Lowell and other mill towns increased. More mills led to overproduction, which led to a drop in prices and profits. Mill owners reduced wages and speeded up the pace of work. The young female operatives organized to protest these wage cuts in 1834 and 1836. Harriet Hanson Robinson was one of those factory operatives; she began work in Lowell at the age of ten, later becoming an author and advocate of women’s suffrage. In 1898 she published Loom and Spindle, a memoir of her Lowell experiences, where she recounted the strike of 1836.

One of the first strikes of cotton-factory operatives that ever took place in this country was that in Lowell, in October, 1836. When it was announced that the wages were to be cut down, great indignation was felt, and it was decided to strike, en masse. This was done. The mills were shut down, and the girls went in procession from their several corporations to the “grove” on Chapel Hill, and listened to “incendiary” speeches from early labor reformers.

One of the girls stood on a pump, and gave vent to the feelings of her companions in a neat speech, declaring that it was their duty to resist all attempts at cutting down the wages. This was the first time a woman had spoken in public in Lowell, and the event caused surprise and consternation among her audience.

Cutting down the wages was not their only grievance, nor the only cause of this strike. Hitherto the corporations had paid twenty—five cents a week towards the board of each operative, and now it was their purpose to have the girls pay the sum; and this, in addition to the cut in the wages, would make a difference of at least one dollar a week. It was estimated that as many as twelve or fifteen hundred girls turned out, and walked in procession through the streets. They had neither flags nor music, but sang songs, a favorite (but rather inappropriate) one being a parody on “I won’t be a nun.”

“Oh! isn’t it a pity, such a pretty girl as I-

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh ! I cannot be a slave,

I will not be a slave,

For I’m so fond of liberty

That I cannot be a slave.”

My own recollection of this first strike (or “turn out” as it was called) is very vivid. I worked in a lower room, where I had heard the proposed strike fully, if not vehemently, discussed; I had been an ardent listener to what was said against this attempt at “oppression” on the part of the corporation, and naturally I took sides with the strikers. When the day came on which the girls were to turn out, those in the upper rooms started first, and so many of them left that our mill was at once shut down. Then, when the girls in my room stood irresolute, uncertain what to do, asking each other, “Would you?” or “Shall we turn out?” and not one of them 1laving the courage to lead off, I, who began to think they would not go out, after all their talk, became impatient, and started on ahead, saying, with childish bravado, “I don’t care what you do, I am going to turn out, whether any one else does or not;‘’ and I marched out, and was followed by the others.

As I looked back at the long line that followed me, I was more proud than I have ever been since at any success I may have achieved, and more proud than I shall ever be again until my own beloved State gives to its women citizens the right of suffrage.

The agent of the corporation where I then worked took some small revenges on the supposed ringleaders; on the principle of sending the weaker to the wall, my mother was turned away from her boarding-house, that functionary saying,” Mrs. Hanson, you could not prevent the older girls from turning out, but your daughter is a child, and her you could control.”

It is hardly necessary to say that so far as results were concerned this strike did no good. The dissatisfaction of the operatives subsided, or burned itself out, and though the authorities did not accede to their demands, the majority returned to their work, and the corporation went on cutting down the wages.

And after a time, as the wages became more and more reduced, the best portion of the girls left and went to their homes, or to the other employments that were fast opening to women, until there were very few of the old guard left; and thus the status of the factory population of New England gradually became what we know it to be to-day.

Note: Harriet Robinson worked in the Lowell Mills intermittently from 1835 to 1848. She was 10 when she started at the mills and 23 when she left them to marry. Presumably, she wrote this account in the 1890s, for it was published in her Loom and Spindle; or, Life among the Early Mill Girls in 1898.

(C) Factory Girls Described by Harriet Hanson Robinson

Source: https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/robinsonfactgirls.html

“When I look back into the factory life of fifty or sixty years ago, I do not see what is called “a class” of young men and women going to and from their daily work, like so many ants that cannot be distinguished one from another; I see them as individuals, with personalities of their own. This one has about her the atmosphere of her early home. That one is impelled by a strong and noble purpose. The other,—what she is, has been an influence for good to me and to all womankind.

Yet they were a class of factory operatives, and were spoken of (as the same class is spoken of now) as a set of persons who earned their daily bread, whose condition was fixed, and who must continue to spin and to weave to the end of their natural existence. Nothing but this was expected of them, and they were not supposed to be capable of social or mental improvement. That they could be educated and developed into something more than work-people, was an idea that had not yet entered the public mind. So little does one class of persons really know about the thoughts and aspirations of another! It was the good fortune of these early mill-girls to teach the people of that time that this sort of labor is not degrading; that the operative is not only “capable of virtue,” but also capable of self-cultivation.

At the time the Lowell cotton-mills were started, the factory girl was the lowest among women. In England, and in France particularly, great injustice had been done to her real character; she was represented as subjected to influences that could not fail to destroy her purity and self-respect. In the eyes of her overseer she was but a brute, slave, to be beaten, pinched, and pushed about.

It was to overcome this prejudice that such high wages had been offered to women that they might be induced to become mill-girls, in spice of the opprobrium that still clung to this “degrading occupation.” At first only a few came; for, though tempted by the high wages to be regularly paid in “cash,” there were many who still preferred to go on working at some more genteel employment at seventy-five cents a week and their board.

But in a short time the prejudice against the factory labor wore away, and the Lowell mills became filled with blooming and energetic New England women. They were naturally intelligent, had mother-wit, and fell easily into the ways of their new life. They soon began to associate with those who formed the community in which they had come to live, and were invited to their houses. They went to the same church, and sometimes married into some of the best families. Or if they returned to their secluded homes again, instead of being looked down upon as “factory girls” by the squire’s or lawyer’s family, they were more often welcomed as coming from the metropolis, bringing new fashions, new books, and new ideas with them.

In 1831 Lowell was little more than a factory village. Several corporations were started, and the cotton-mills belonging to them were building. Help was in great demand; and the stories were told all over the country of the new factory town, and the high wages that were offered to all classes of work-people,—stories that reached the ears of mechanics’ and farmers’ sons, and gave new life to lonely and dependent women in distant towns and farmhouses. Into this Yankee El Dorado, these needy people began to pour by the various modes of travel known to those slow old days. The stage-coach and the canal-boat came every day, always filled with the new recruits for this army of useful people. The mechanic and machinist came, each with his home-made chest of tools, and oftentimes his wife and little ones. The widow came with her little flock of scanty housekeeping goods to open a boarding-house or variety store, and so provided a home for her fatherless children. Many farmers’ daughters came to earn money to complete their wedding outfit, or buy the bride’s share of housekeeping articles.

Women with past histories came, to hide their griefs and their identity, and to earn an honest living in the “sweat of their brow.” Single young men came, full of hope and life, to get money for an education, or to lift the mortgage from the home-farm. Troops of young girls came by stages and baggage-wagons, men often being employed to go to other States and to Canada, to collect them at so much a head, and deliver them to the factories….

These country girls had queer names, which added to the singularity of their appearance. Samantha, Triphena, Plumy, Kezia, Aseneth, Elgardy, Leafy, Ruhamah, Lovey, Almaretta, Sarepta, and Flotilla were among them.

Their dialect was also very peculiar. On the broken English and Scotch of their ancestors was ingrafted the nasal Yankee twang; so that many of them, when they had just come down, spoke a language almost unintelligible. But the severe discipline and ridicule which met them was as good as a school education, and they were soon taught the “city way of speaking”…

(D) Letter from Mary Paul to her Family (1845)

https://www.albany.edu/history/history316/MaryPaulLetters.html

“I received your letter on Thursday the 14th with much pleasure. I am well which is one comfort. My life and health are spared while others are cut off. Last Thursday one girl fell down and broke her neck which caused instant death. She was going in or coming out of the mill and slipped down it being very icy. The same day a man was killed by the [railroad] cars. Another had nearly all of his ribs broken. Another was nearly killed by falling down and having a bale of cotton fall on him. Last Tuesday we were paid. In all I had six dollars and sixty cents paid $4.68 for board. With the rest I got me a pair of rubbers and a pair of 50.cts shoes. Next payment I am to have a dollar a week beside my board. We have not had much snow the deepest being not more than 4 inches. It has been very warm for winter. Perhaps you would like something about our regulations about going in and coming out of the mill. At 5 o’clock in the morning the bell rings for the folks to get up and get breakfast. At half past six it rings for the girls to get up and at seven they are called into the mill. At half past 12 we have dinner are called back again at one and stay till half past seven. I get along very well with my work. I can doff as fast as any girl in our room. I think I shall have frames before long. The usual time allowed for learning is six months but I think I shall have frames before I have been in three as I get along so fast. I think that the factory is the best place for me and if any girl wants employment I advise them to come to Lowell. Tell Harriet that though she does not hear from me she is not forgotten. I have little time to devote to writing that I cannot write all I want to. There are half a dozen letters which I ought to write to day but I have not time. Tell Harriet I send my love to her and all of the girls. Give my love to Mrs. Clement. Tell Henry this will answer for him and you too for this time.”