The Day the Markets Roared: How A 1982 Forecast Sparked a Global Bull Market

By Henry Kaufman and David B. Sicilia

Book Review by Hank Bitten, NJCSS Executive Director

The lessons of history are very important for students to understand. The laws of economics and the functionality of markets are essential for understanding our current troubled century. Students taking U.S. History in New Jersey are required to learn the following in their study of the post-World War II economy.

• 6.1.12.EconNE.14.a: Use economic indicators to evaluate the effectiveness of state and national fiscal (i.e., government spending and taxation) and monetary (i.e., interest rates) policies.

• 6.1.12.EconNE.14.b: Use financial and economic data to determine the causes of the financial collapse of 2008 and evaluate the effectiveness of the government’s attempts to alleviate the hardships brought on by the Great Recession.

• 6.1.12.EconET.14.a: Use current events to judge what extent the government should intervene at the local, state, and national levels on issues related to the economy.

• 6.1.12.EconET.14.b: Analyze economic trends, income distribution, labor participation (i.e., employment, the composition of the work force), and government and consumer debt and their impact on society.

• 6.1.12.EconEM.14.a: Relate the changing manufacturing, service, science, and technology industries and educational opportunities to the economy and social dynamics in New Jersey.

The Day the Markets Roared is a concise economic history of the last 45 years. It is a personal account and perspective written by one of America’s top researchers on the economy with an understanding of the role of stocks and bonds in a dynamic global economy. In 1982, the American economy was faced with unprecedented debt, an unemployment rate of 10.8%, a double-digit rate of inflation, a strong dollar, and high-income tax rates.

“The economy entered 1982 in a severe recession and labor market conditions deteriorated throughout the year. The unemployment rate, already high by historical standards at the onset of the recession in mid-1981, reached 10 .8 percent at the end of 1982, higher than at any time in post-World War II history.

The current recession followed on the heels of the brief 1980 recession, from which several key goods industries experienced only limited recovery. Housing, automobiles, and steel, plus many of the industries that supply these basic industries, were in a prolonged downturn spanning 3 years or more and bore the brunt of the 1981-82 job cutbacks.

Unemployment rose throughout 1982 and, by September, the overall rate had reached double digits for the first time since 1941. A total of 12 million persons were jobless by yearend-an increase of 4.2 million persons since the prerecession low of July 1981.’ Unemployment rates for every major worker group reached postwar highs, with men aged 20 and over particularly hard hit.” Bureau of Labor Statistics

The book begins on a cloudy, humid Tuesday morning, August 17, 1982, in Wyckoff, New Jersey. As Henry Kaufman enters the Lincoln Town Car at 6:30 a.m. he is traveling to a meeting of the Salomon Brothers Executive Committee at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue in Manhattan. In the hour-long ride to the meeting, he is editing a memo to his office secretary, Helen Katcher that will be released to clients and the press shortly after 8:30 a.m. and before the opening of the bond markets at 9:00 a.m. and the stock markets in New York at 9:30 a.m.

The Reagan Recession of 1981-82

The first years of the Reagan presidency faced global insecurity with a Soviet arms buildup in Eastern Europe, Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, conflicts in Lebanon and the Middle East, Falkland Islands, Nicaragua, and Grenada, an unpopular grain embargo from the Carter Administration, and a rising federal deficit and debt due to military spending. These were difficult challenges requiring the monitoring of the M1 and M2 money supply accounts, bank balance sheets, and revolving credit expenses.

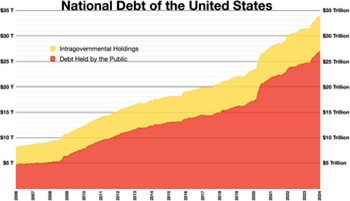

The current challenges for our economy and financial stability are the validity of information, the dependency of the federal government on the Federal Reserve System as either the lender of ‘last resort’ or ‘first resort,’ declining credit ratings of governments and corporations, and the fact that short-term liabilities are rarely paid off. The federal deficit of the United States government is 33 trillion dollars and increased borrowing for social security, Medicare, infrastructure improvements, and assistance from extreme weather events are hurricane force winds facing our economy.

As of June 2024, the federal debt is $34.55 trillion dollars and between 110% and 117% of our annual GDP with full employment and moderate inflation.

It is critical that social studies teachers integrate economic history into their lessons, encourage problem-solving and decision-based case studies, engage students in discussions with local financial experts in your community, an understanding of where money comes from, and the differences between the tax and money multipliers.

- What are the effects of a 10% protective tariff?

- How does a 1% change in the rate of inflation affect the federal budget?

- How do changes in the federal income tax structure affect the national economy?

- What are the implications of a decrease in the credit rating of the United States? Why does a credit rating change?

- Will the increased demands of the federal government to finance its debt through bonds lead to ‘crowding out’ for municipal, state, and private corporations?

- Who will be the effective borrowers in the next decade?

Students will also gain valuable lessons through engaging conversations through their analysis of excerpts from the classical economists of Adam Smith, David Riccardo, and Thomas Malthus. Perspectives of Karl Marx, Joseph Schumpeter, Frederick Hayek, Milton Friedman, Paul Samuelson, and others are important. Consider a dinner conversation, Madame Tussauds Wax Museum Hall of Fame, Press Conference, or digital video production. Here is an example of a reference in the book.

“Adam Smith remains a useful guide to the hallmarks of capitalism. In The Wealth of Nations (1776), he argued that humans innately strive for material progress, and the best way to get there is through unfettered competition, the division of labor, and free trade. Smith argued that the state should play a limited role in economic affairs. Governments should be properly confined to national security, the rule of law-including the protection of private property – and the provision of a few public goods which as education. He also cautioned against sharp class divisions that might idle rich people and exploit workers. ‘No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members is poor and miserable.’” (Kaufman, Page 167)’

One final observation about The Day the Markets Roared is the insights into the internal operations of businesses before the age of social media. The lessons of power, leadership, profit motive, media image, responding to a crisis, understanding how financial markets react to political changes are revealed in Chapters 3-7.

The book is easy to read, includes interesting insights and perspectives, and is one of the few books I am aware of that provide a concise and accurate economic history of the 1970s and 1980s.