Teaching with Documents: The 1892 Lynching of an African American Man in New York State

Alan Singer and Janice Chopyk

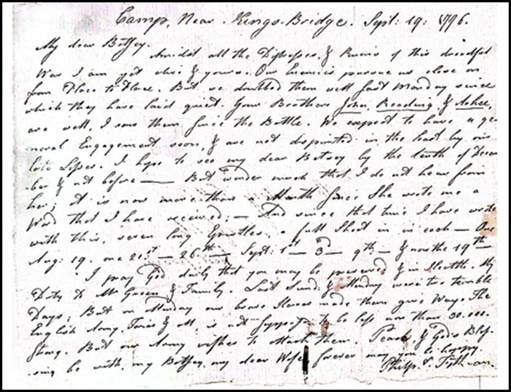

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama memorializes the over 4,000 African Americans murdered by vigilante terrorism in the American South between the end of Reconstruction in the United States in 1877 and 1950 and the more than 300 victims of racial terrorism in other states. Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia were the worst offenders, but there were also significant numbers of vigilante murders of African Americans in Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. Eight hundred steel columns hang from the ceiling at the Memorial, each with the name of a county where a lynching occurred with the names of victims engraved on it. The only lynching in New York State during this period occurred in the town of Port Jervis, Orange County in 1892. Port Jervis is located on the Delaware River at the border of New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. At the end of the 19th century, it was an important stop on the Delaware and Hudson Canal for barges transporting anthracite coal to Philadelphia and New York City from Scranton area coal mines and on the New York, Lake Erie and Western Railroad.

In his new book, A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022), Philip Dray documents racial violence in Port Jervis about sixty-five miles northwest of New York City. The story of what happened to Robert Lewis, a 28-year-old African American teamster and coach driver on Thursday June 2, 1892 was largely told through the eyes of white residents and white-owned newspapers. Unfortunately, there are no sources that address the Black perspective on the lynching of Lewis by a white mob. A coroner’s inquest was held with witness testimony, but there is no surviving transcript. At least one witness, Officer Simon Yaple, is known to have named some of the members of the murderous mob, but none were ever tried or convicted of crimes.

Robert Lewis, described in the press as a powerful man of about five feet seven and 170 pounds, was accused of assaulting and sexually abusing a 22-year-old white woman named Lena McMahon on a riverbank where the Cuddeback Brook meets the Neversink River before it flows into the Delaware River just south of Port Jervis. Participants in the mob attack on Lewis claimed that before he was murdered, Lewis confessed to the assault and implicated McMahon’s white boyfriend, Philip Foley as an accomplice. Lewis was then lynched on East Main Street, now U.S. Route 6.

Lena McMahon reported to authorities that she was approached by a heavy-set Black man with a light complexion who she did not know, although he appeared to know her. In her testimony about the assault, McMahon claimed that she was “terribly frightened” because her assailant had an “evil look in his eyes” and that after she rebuffed him he grabbed her shoulder and covered her mouth in an attempt to keep her from screaming. Local boys interrupted the attack on McMahon and her attacker, presumably Lewis, picked up fishing gear and left the scene. While McMahon initially reported that the man who attacked her was a “tramp,” one of the boys later identified Lewis as the assailant.

Robert Lewis was seized by a posse on the towpath of the D & H Canal while riding on a slow moving coal barge, not a very likely escape plan and Lewis made no effort to avoid capture. He had fishing gear with him and said he was planning to spend the night fishing. Sol Carley, part of the posse that captured Lewis, claimed that he questioned Lewis while they were bringing him back to Port Jervis. According to Carley, Lewis confessed to what had taken place, but claimed that Foley, who he knew from the hotel where he previously worked, told him McMahon would be receptive to a sexual encounter and if he wanted a “piece to go down and get it.” Lewis seemed to think that the entire situation could be resolved if they questioned Foley and Lewis had a chance to speak to McMahon’s father.

The initial police plan was to bring Lewis to the McMahon home to see if she could identify him, although Lena McMahon continued to maintain her attacker was a stranger, probably a tramp, who was camping in the woods. This plan was interrupted when a rumor spread that Lena McMahon had died from her wounds, dooming Robert Lewis. A crowd of over 300 white men was gathered in downtown Port Jervis. Upon hearing the rumor, it was transformed into an uncontrollable mob and murdered Lewis. Port Jervis’ small African American community, in defiance of white authority, insisted on a proper funeral for Lewis and contributed funds for burial at Laurel Grove cemetery, while at least some whites tried to steal souvenir relics from his body.

Students can read, compare, and discuss newspaper coverage of the events in Port Jervis. In the age of #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, it is difficult to dissect aspects of events that took place over a hundred years ago, especially where the surviving documentation is sporadic and clearly biased. How much of Lena McMahon’s story should be believed? Does questioning her account reflect what we now recognize as gender bias? On the other hand, how much of her story was colored by racism? We know from similar accusations made by white women against Black men that led to the arrest and imprisonment of the Scottsboro Boys and the murder of Emmett Till, that in a climate of intense racism, white women protected their reputations by fabricating stories of disrespect or assault. It is hard to believe that Robert Lewis did not know that a “confession” meant a death sentence. A compelling question for students to consider is: What do the events in Port Jervis and the newspaper coverage tell us about race and racism in New York State during this period? Teachers should alert students that there are overtly racist comments in the newspaper articles, but that “negro” was in common usage at the time to describe the group of people we now call African American and was not a racist term.

Documenting the Lynching of Robert Lewis at Port Jervis, New York

A. LYNCHED AT PORT JERVIS. ROBERT JACKSON, A COLORED MAN, HANGED BY A MOB. New York Times, June 3, 1892

Robert Jackson, a young colored man, was lynched in this village to-night, receiving swift retribution for an assault committed this morning on Miss Lena McMahon, daughter of John McMahon of this place. The crime occurred on the outskirts of the village, near the banks of the Neversink River. Two young negroes and a crowd of children were near by, but when the former tried to interfere Jackson kept them at bay with a revolver. He made his escape without trouble. Miss McMahon was left in an insensible condition. Her injuries may prove fatal. A posse started in pursuit of Jackson as soon as news of the assault spread . . . The capture of the fugitive was finally made at Cuddebackville, a small village on the Delaware and Hudson Canal about nine miles from Port Jervis, by Sol Carley, Duke Horton, and a man named Coleman. Jackson had borrowed a canal boat at Huguenot, and had reached Cuddebackville, when he was overtaken by the three men. On the way back to this village he confessed the crime, and implicated William Foley, a white man, who, he said, was in the conspiracy against Miss McMahon. Foley has been paying attention to the girl contrary to the wishes of her parents, and the feeling against him in this community is such that, should he be taken, a fate similar to that which has overtaken Jackson would probably be meted out to him. The news of the capture of Jackson soon spread through the town, and a large crowd of men collected about the village lock-up, awaiting the arrival of the prisoner. The word was whispered through the crowd “Lynch him, lynch him!” The suggestion spread like wildfire, and it was evident that the fate of the prisoner was sealed. On his arrival at the lock-up Jackson was taken in hand by the mob. The village police endeavored to protect him, but their efforts were unavailing. It was at first proposed to have Jackson identified by his victim before hanging him, in order to make sure of his guilt. With this object in view the mob tied a rope around his body and dragged him up Hammond and down Main Streets as far as the residence of E. G. Fowler, Esq. By this time the mob had reached a state of uncontrollable excitement, and it was decided to dispatch him without further ceremony. A noose was adjusted about his neck and he was strung up to a neighboring tree in the presence of over 1,000 people. For an hour the body hung from the tree, where it was viewed by crowds . . . Public sentiment on the subject of the lynching is divided, although a majority approve and openly applaud the work of the lynchers, declaring that a terrible warning was necessary to prevent future repetitions of the same offense.

Questions

- Where and when did these events take place?

- Who was Robert Jackson?

- What was Robert Jackson accused of?

- What happened to Robert Jackson?

- What is the attitude of the New York Times toward these events? What evidence from the text supports your conclusion?

B. Mob Murder at Port Jervis, Brooklyn Eagle, June 3, 1892, pg. 4

A negro was hanged by a mob in Port Jervis on Thursday night. He was charged with the crime of violence on a white girl, who is now said to be lingering between life and death. The crime was committed. The victim of it and two other witnesses charged the commission of it on a negro called by the name of the one who was lynched. The accused criminal was caught a long distance from the spot, while trying to run away. He was not, however, taken for identification before any of the persons who had accused him. A rumor prevails around Port Jervis that, after all, the wrong negro was captured and killed. Negroes are not easily distinguished from one another, unless by marks of identification carefully registered on scientific examination and then carefully compared when any man to whom they presumably refer is apprehended. There is very little doubt that the negro who was killed was the man who committed the crime, but there is some doubt that he was. That doubt, however slight, should harrow the memories and consciences of the men who lawlessly destroyed him. Aside from this fact, the offense of which the negro was accused but not convicted does not carry the punishment of death in this state by law. http://www.bethlehemchurch.com/admin/Law has found that capital punishment in cases of violence against women has been inflicted on innocent persons. The accusation is easily made. It is hard to disprove. A predisposition to believe it exists when it is brought against the lowly and the humble, the obscure or the repulsive. The pardoning power is not seldom required to rectify the errors of courts and juries in cases of violence to women. On these accounts the punishment has been reduced below the death penalty, to give time and government a chance to correct the wrongs of law. The event at Port Jervis, Thursday night, was a disgrace to the State of New York. The heinousness of the offense may explain but does not excuse the popular violence. This is supposed to be a government of law. Citizens are supposed to be law abiding. Moral culture and obedience to law are supposed to be an insurance that communities will not take the law in their own hands in any cases, and especially in cases which excite and inflame them. It may be roughly said, so far as lynch law is concerned in New York State, that the greater the provocation the less the excuse. The crime of which this negro was guilty cannot be overcharacterized, but there are worse crimes than it, by the definition of the law of the State of New York. A worse crime is murder. Murder is the destruction of a human being without warrant of law, with malice and premeditation, and not in self defense. The hanging of the negro in Port Jervis on Thursday night mates with that definition of the crime of murder. It was murder.

Questions

- Are there features in the Brooklyn Eagle article you would identify as racist? Explain.

- Compare coverage of the events in Port Jervis as reported in the Brooklyn Eagle the New York Times. How is it similar or different?

- In your opinion, are there errors of fact in the Brooklyn Eagle account? Explain.

C. Port Jervis Disgrace, The Daily Standard Union, June 3, 1892, pg. 2

Port Jervis has not added to her good name by the brutal murder of a negro, who was, no doubt, no less brutal than the white men who took the law into their own hands and inflicted the death penalty without sentence. Has the Empire State fallen so low that criminals cannot be punished by due process of law? . . . There is no reason why a Northern State inhabited by justice-loving people, should be Southernized by a few misguided men in a country town. A heinous crime was charged against the negro, but there was no sworn evidence that he was the guilty person. Sympathy was strong for the young woman who, it is said, suffered from the negro’s violence, and this sympathy was proper and creditable; but it does not justify killing by mass meeting. It is to be hoped that every one of the men who actually took part on compassing the negro’s death will be apprehended and made to feel the hand of the law he has outraged.”

Questions

- How is coverage of the events in Port Jervis in this article from the Daily Standard Union, a Brooklyn, New York newspaper, similar to and different from coverage in the New York Times and the Brooklyn Eagle?

- What is conspicuously missing from this excerpt from the article? In your opinion, what does that suggest about the viewpoint of the Daily Standard Union about the events?

D. Local Newspaper Coverage

Port Jervis Union: The Excitement in this village over the lynching of the negro, Robert Lewis has abated somewhat but further developments are awaited with the most intense interest. Attention is now centered upon the work of the coroner’s jury which was empanelled yesterday and whose duty it is not merely to investigate the manner of Lewis’ death but if possible to trace out the leaders and instigators of mob violence and to fix upon them the responsibility which belongs to them. Public sentiment and the honor and fair fame of the village demand that an earnest effort be made to do this. Now that the excitement attendant upon the awful events of Thursday has partially subsided a decided reaction has taken place in public sentiment and there are few who do not deplore and condemn the work of the mob. It is now generally admitted that the ends of justice would have been fully satisfied by leaving Lewis to be dealt with according to the regular forms of law, while our village would have escaped the world-wide notoriety which now attaches to it as the scene of one of the worst manifestations of mob-violence which has occurred in recent years. To be known as a community controlled and dominated by lawless elements is a penalty which we must now pay.

Middletown Daily Press: What a hard question to decide: the right or the wrong of Thursday night’s outrage in Port Jervis. One man, a father, and a county official, said: “It’s all right for some of us to moralize. But put yourself in that father’s place.” Another man, also a father: “Those men are worse than the negro. No matter how heinous the crime, can any human being think of a life being tugged along through public streets by a howling, half mad crowd which handled the rope, without saying ‘They’re brutes, and God does not sanction their work.’”

Middletown Argus: That the punishment so summarily meted out to the black ruffian who made Lena McMahon victim of his lust was more than merited, there is no division of sentiment . . . Lewis might better have been left to be dealt with by court and jury, inadequate though his punishment, if convicted, would be, but informal as was his exit from it, no one will say nay to it that the world is well rid of him.

Newburgh Daily Journal: The outbreak in Port Jervis is wholly without justification . . . The mob’s crime was an attack upon the cause of law and order. It remains with the criminal authorities to deal with the perpetrators of this crime as the law provides.

Questions:

- The Port Jervis Union is a weekly newspaper. This issue was published two days after the events and coverage is on page 3. What is the primary focus of the article? What does this suggest about local attitudes toward the event?

- What are the attitudes toward the events in Port Jervis expressed in newspaper coverage from neighboring towns?

E. The Dangers of Lynching (Editorial). New York Times, June 4, 1892

A considerable number of persons, some of them possibly very worth citizens in a general way and others pretty certainly nothing of the kind, united on Thursday in Port Jervis to hang a negro who had committed a criminal assault upon a white girl. The feeling that actuated the mob was doubtless the same that is cited as defense for like lynching in the Southern States. It is that the penalty prescribed by law is not sufficient for the offense which is punished by lynching. It is not to be denied that negroes are much more prone to this crime than whites, and the crime itself becomes more revolting and infuriating to white men, North as well as South, when a negro is the perpetrator and a white woman the victim . . . It is unlikely that such a change in the law would diminish the number of lynchings. These are commonly committed by crowds which are animated by so furious an indignation that they would not wait for the law to take its course, even though the punishment were capital and certain, but would insist upon themselves doing their prisoner to death rather than to wait for months, or even weeks, to have him done to death by the law. This lawless temper is not commendable, and it ought to be discouraged by the law. Although it is probable that the good citizens of Port Jervis sympathized with the mob when they first learned of its murderous work, it is also probable that they are by this time ashamed of it and of their sympathy with it, and regard the lynching as more of a disgrace to the town than the crime it avenged, for which only a single brute was responsible . . . [I]t is admitted that the mob, misled by one of the rumors that spread in times of excitement, came very near hanging the wrong man, and this is a danger that always attends the unlawful execution of justice . . . [T]he lynchers by their precipitation seem to have operated a defeat of justice almost as great as if they had hanged the wrong man. The negro not only confessed his crime, but declared that he had been instigated to commit it by a white man whom he named. . . . The greater criminal, if he be a criminal at all, is likely to go scot free because the people of Port Jervis have hastily and carelessly hanged a man who, if he had been spared, might have proved a valuable witness. This is a danger of lynching that the lynchers have incurred which they themselves must confess to be a serious drawback to the success of their method of doing justice.

Questions

- How does the New York Times describe the people who participated in the lynching of Robert Lewis?

- In the opinion of the New York Times, why is the incident regrettable?

- What evidence, if any, does the excerpt from the editorial suggest about the biases of the Times?

F. VERDICT AT PORT JERVIS, No One Held Responsible for the Lynching of Lewis. The Aspen Daily Chronicle, June 15, 1892, pg. 3

The coroner’s inquest over the lynching of Bob Lewis, the negro, terminated at 4:30 o’clock yesterday afternoon. The jury, after being out one hour, rendered the following verdict: “We find that Robert Lewis came to his death in the village of Port Jervis on June 2, 1892, by being hanged by some persons or person unknown to this jury . . . The thinking public doubts Miss McMahon’s story, as it also does Foleys . The circumstances are to conflicting. If the young woman had practically no knowledge of her surroundings from Wednesday to Thursday morning, then she must have been crazy. Not a living female would or could be hired to stay over night in Laurel Grove cemetery, as she stated she did. The stormy weather and the delicate physique of the girl would knock that story in the head. It is a fact that when Foley was arrested on the morning succeeding the assault of Miss McMahon, he trembled like a leaf and had to be supported. There is something back of the whole affair and those facts are held by Squire Mulley justice of the peace, who refuses to allow the contents of Foleys blackmailing letters addressed to Miss McMahon, to appear in print. Mr. Mulley says that the investigation of Miss McMahon and Foley will be strictly private.

Questions

- What was the verdict of the coroner’s inquest?

- What is the attitude of this newspaper to stories of the incident?

- This article appeared in a Colorado newspaper. What does that suggest about reaction to the lynching?

G. MISS M’MAHON WRITES A LETTER, SHE EXPLAINS WHAT HER RELATIONS WERE WITH FOLEY. New York Times, June 25, 1892:

To the Editor of the Daily Union:

Sir: As my name has been so freely circulated throughout the press of the country during he past few weeks in connection with the infamous scoundrel, Foley, who has been airing his ignorance and viciousness in frequent letters from the county jail, that I wish, once for all, in justice to myself, to refute and brand as malicious falsehoods the statements this person has seen fit to utter. I first became acquainted with Foley when he assumed to be a gentleman, through the introduction of a mutual friend. He paid me attention, and I was foolish, as other young girls have been, to believe in his professions of friendship, and when I, in the indiscretion of youth, had some trifling difficulty with fond and loving parents who endeavored to give me wise counsel and advice, resolved to leave home, this inhuman monster egged me on and endeavored to carry into execution his nefarious scheme to ruin and blacken my character forever. When I discovered “the wolf in sheep’s clothing,” the true character of the parody of manhood, I at all risks and perils resolved to prosecute him as he so richly deserves. That resolution I still maintain, and I wish to assure the public that the maudlin, sentimental outpourings from this person, who, relying upon the fact that I was once his friend, has seen fit to make me the victim of extortion and blackmail, have no effect whatever on me, and it will not be my fault if he does not receive the punishment he so richly deserves. There is nothing to prevent this man writing letters, and I do not consider it either wise or discreet to pay any attention to them. I simply desire to say that his insinuations and allegations are falsehoods; that my relations with him have been those only of a friend. God only knows how much I regret that. I cannot have my reputation as an honest, chaste, and virtuous girl assailed by this villain without a protest, and I ask all right-thinking people who possess these qualities to place themselves in my position and then ask if they would act differently than I have done. The evil fortune that has overtaken me has been no fault of my own, and I trust that the light of truth will reveal this man as he truly is, the author of all my misfortune. I do not intend to express myself again to the public concerning this matter, nor pay any attention to what this man may say or do. All I desire is peace, and the consideration and fair treatment that should be extended to one who has suffered untold misery, and whose whole life has been blighted by one whose heartlessness and cruelty is only equaled by his low cunning and cowardice. LENA M’MAHON.

Questions

- Who is Lena McMahon?

- What prompted her to write this letter?

- What is missing from the letter?

- What does the missing part tell us about events in Port Jervis?

H. Port Jervis Lynching Indictments. New York Times, June 30, 1892

The Grand Jury of Orange County to-day indicted nine persons in the Port Jervis lynching case. Two of these were officers of the village . . . Five of the indictments are for assault and the rest for riot.

Arrested for the Port Jervis Lynching. New York Times, July 1, 1892

Bench warrants for the arrest of five men indicted by the Grand Jury, and alleged to have been in the party who lynched the negro in this place, were issued to-day . . . The indictment is regarded as the weakest that could have been made.

Port Jervis Lynchers Not Indicted. New York Times, September 30, 1892

The Orange County Grand Jury reported to-day to Judge John J. Beattie. They said they had not indicted the Port Jervis lynchers of the colored man Robert Lewis. The reason was that the Port Jervis people had failed to give the evidence necessary to indict.

Questions

- What was the final resolution of the Port Jervis lynching?

- In your opinion, what does this tell us about race and justice in New York in this period?

References

Dray, Philip. 2022. A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022).