Teaching Controversial Issues: Teachers’ Freedom of Speech in the Classroom

Arlene Gardner

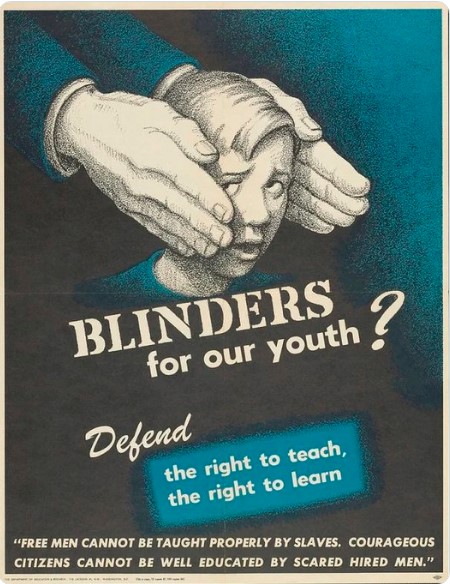

What is the purpose of education? The conventional answer is the acquisition of knowledge. Looking beyond this facile response, most people will agree that the true purpose of education is to produce citizens. One of the primary reasons our nation’s founders envisioned a vast public education system was to prepare youth to be active participants in our system of self-government. John Dewey makes a strong case for the importance of education not only as a place to gain content knowledge, but also as a place to learn how to live. In his eyes, the purpose of education should not revolve around the acquisition of a predetermined set of skills, but rather the realization of one’s full potential and the ability to use those skills for the greater good.

Democratic self-government requires constant discussions and decisions about controversial issues. There is an intrinsic and crucial connection between the discussion of controversial political issues and the health of democracy. If we want our students to become informed, engaged citizens, we need to teach them how to “do” democracy by practicing the skills of discussing controversial issues in the classroom and learning how to respectfully disagree.

Research has demonstrated that controversy during classroom discussion also promotes cognitive gains in complex reasoning, integrated thinking, and decision-making. Controversy can be a useful, powerful, and memorable tool to promote learning. In addition to its value in promoting skills for democracy, discussing current controversial public issues:

- Is authentic and relevant

- Enhances students’ sense of political efficacy

- Improves critical thinking skills

- Increases students’ comfort with conflict that exists in the world outside of the classroom

- Develops political tolerance

- Motivates students

- Results in students gaining greater content knowledge.

(Diana Hess, Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion (2009); Nel Noddings and Laurie Brooks, Teaching Controversial Issues: The Case for Critical Thinking and Moral Commitment in the Classroom (2017); “Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools” (2011); Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, University of Michigan at https://crlt.umich.edu/tstrategies/tsd).

Yet, teachers may consciously (or unconsciously) avoid controversial issues in the classroom because of the difficulty involved in managing heated discussions and/or for fear that parents will complain or that the school administration will admonish or punish them for “being controversial.” These concerns are certainly not groundless. How well are teachers protected from negative repercussions if they address controversial issues in their classrooms? How extensive are teachers’ First Amendment rights to free speech? How can heated disagreements among students be contained in the classroom?

Two different legal issues exist regarding free speech rights of teachers: The First Amendment directly protects a teacher’s personal right to speak about public issues outside of the classroom and “Academic Freedom” protects a teacher’s right and responsibility to teach controversial issues in the classroom. However, both have certain limitations.

First Amendment protection of public speech by teachers

Although the First Amendment free speech protection is written in absolute terms (“Congress shall make no law…”), the courts have carved out several exceptions (for national security, libel and slander, pornography, imminent threats, etc.). The courts have also carved out a limited “government employee” exception based on the rationale that a government employee is paid a salary to work and contribute to an agency’s effective operation and, therefore, the government employer must have the power to prevent or restrain the employee from doing or saying things that detract from the agency’s effective operation. Thus, the government has been given greater latitude to engage in actions that impose restrictions on a person’s right to speak when the person is a governmental employee, which includes teachers who work in public schools.

Some of the earliest threats to the free speech rights of public school teachers were the loyalty oaths that many states imposed on government employees during the ‘‘red scare’’ and early ‘‘cold war’’ years of American history. In Adler v. Board of Education (1952), the Supreme Court in a 6-3 decision rejected First Amendment claims and upheld a New York statute designed to enforce existing civil service regulations to prevent members of subversive groups, particularly of the Communist Party, from teaching in public schools. The Supreme Court effectively overturned this ruling in the 1960s and declared several loyalty oath schemes to be unconstitutional because they had chilling effects on individuals which violated their First Amendment rights (Baggett v. Bullitt (1964); Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction (1961); and Keyishian v. Board of Education (1967)).

Much of the reasoning regarding the “government employee” exception to the First Amendment outlined in Adler was abandoned altogether in the 1968 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Pickering v. Board of Education. Teacher Marvin Pickering had written a letter complaining about a recently defeated school budget proposal to increase school taxes. The school board felt that the letter was “detrimental to the efficient operation and administration of the schools” and decided to terminate Pickering, who sued claiming his letter was protected speech under the First Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court held that Pickering’s dismissal violated his First Amendment right to free speech because public employees are entitled to the same measure of constitutional protection as enjoyed by their civilian counterparts when speaking as “citizens” and not as “employees.”

In Mt. Healthy City School District v. Doyle (1977), non-tenured teacher Fred Doyle conveyed the substance of an internal memorandum regarding a proposed staff dress code to a local radio station, which released it. When the board of education refused to rehire him, Doyle claimed that his First and Fourteenth Amendment rights had been violated. The court developed a “balancing test” that required the teacher to demonstrate that the speech act was a ‘‘substantial’’ or ‘‘motivating factor’’ in the administration’s decision and gave the school board the opportunity to demonstrate, based on the preponderance of the evidence, that the teacher’s speech act was not the ‘‘but for’’ cause of the negative consequences imposed on the teacher by the school board. Finally, the court would “balance” the free speech interests of the teacher and the administrative interests of the school district to determine which carried more weight. Based on this test, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the teacher’s call to the radio station was protected by the First Amendment, that the call played a substantial part in the board’s decision not to rehire Doyle, and that this action was a violation of Doyle’s rights under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

In a 5/4 decision in Connick v. Meyers (1983), the U.S. Supreme Court held that speech by public employees is generally only protected when they are addressing matters of public concern, not personal issues. Sheila Meyers was an Assistant District Attorney who had been transferred. She strongly opposed her transfer and prepared a questionnaire asking for her co-workers views on the transfer policy, office morale and confidence in supervisors. She was terminated for insubordination. Meyers alleged her termination violated her First Amendment right to free speech. The district court agreed and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. However, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed because Meyer’s speech only dealt with personal not public issues. “When a public employee speaks not as a citizen upon matters of public concern, but instead as an employee upon matters only of personal interest, absent the most unusual circumstances, a federal court is not the appropriate forum in which to review the wisdom of a personnel decision taken by a public agency allegedly in reaction to the employee’s behavior.” Although the case involved an Assistant District Attorney, it is applicable to all public employees: teachers must demonstrate that their speech is of public concern.

This was confirmed in Kirkland v. Northside Independent School District (1989) where the school district did not rehire non-tenured teacher Timothy Kirkland because of poor performance and substandard teaching evaluations. Kirkland filed a lawsuit in federal district court against Northside, claiming that he was not rehired in violation of his First Amendment rights after he gave his students a reading list that was different from Northside’s list. Northside argued that Kirkland had no right to substitute his list without permission or consent and he had failed to obtain either. The district court ruled in favor of Kirkland and Northside appealed. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and dismissed Kirkland’s complaint, holding that Kirkland’s “speech” did not infringe on any matter of public concern and was in fact “private speech.” If the nature of the speech is purely private, such as a dispute over one employee’s job performance, judicial inquiry then comes to an end, and the question of whether the employee’s speech was a substantial or motivating factor in the decision not to rehire him need not even be reached. The U.S. Supreme Court denied cert, leaving this decision in place.

Academic freedom

Although primarily used in the context of university faculty rights, “Academic Freedom” protects a teacher’s ability to determine the content and method of addressing controversial issues in the classroom. This is more limited at the K-12 level because the courts have long held the view that the administration of K-12 public schools resides with state and local authorities. Primary and secondary education is, for the most part, funded by local sources of revenue, and it has traditionally been a government service that residents of the community have structured to fit their needs. Therefore, a teacher’s “Academic Freedom” is limited to his or her content and method of teaching within the policies and curriculum established by the state and local school board. By finding no First Amendment violation, the court in Kirkland implicitly held that he had no right to substitute his own book list for the one approved by the district without permission or consent, which he failed to obtain.

In an early case, following the end of World War I, Nebraska had passed a law prohibiting teaching grade school children any language other than English and Robert Meyer was punished for teaching German at a private Lutheran school. The court held that the Nebraska law was an unnecessarily restrictive way to ensure English language learning and was an unconstitutional violation of the 14th Amendment due process clause (the 14th Amendment had not yet applied the First Amendment to the states until Gitlow v. New York in 1925) that exceeded the power of the state (Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923).

“The Fourteenth Amendment, as now applied to the States, protects the citizen against the State itself and all of its creatures-Boards of Education not excepted. These have, of course, important, delicate, and highly discretionary functions, but none that they may not perform within the limits of the Bill of Rights. That they are educating the young for citizenship is reason for scrupulous protection of Constitutional freedoms of the individual, if we are not to strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of our government as mere platitudes.” Justice Jackson in West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnett (1943)(holding unconstitutional a requirement that all children in public schools salute the flag).

The Supreme Court has more than once instructed that “[t]he vigilant protection of constitutional freedoms is nowhere more vital than in the community of American schools” (Shelton v. Tucker (1960)). In Epperson v. Arkansas (1968)(a reprise of the famous 1927 “Scopes Trial”), the Arkansas legislature had passed a law prohibiting teachers in public or state-supported schools from teaching, or using textbooks that teach, human evolution. Sue Epperson, a public school teacher, sued, claiming that the law violated her First Amendment right to free speech as well as the Establishment Clause. A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court declared the state law unconstitutional. The Court found that “the State’s undoubted right to prescribe the curriculum for its public schools does not carry with it the right to prohibit, on pain of criminal penalty, the teaching of a scientific theory or doctrine where that prohibition is based upon reasons that violate the First Amendment.” Seven members of the court based their decision on the Establishment Clause, whereas two concurred in the result based on the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment (because it was unconstitutionally vague) or the Free Speech clause of the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court, however, has not clearly defined the scope of academic freedom protections under the First Amendment, and commentators disagree about the scope of those protections. (See, e.g., William W. Van Alstyne, “The Specific Theory of Academic Freedom and the General Issue of Civil Liberty,” in The Concept of Academic Freedom 59, 61-63 (Edmund L. Pincoffs ed., 1972); J. Peter Byrne, “Academic Freedom: A ‘Special Concern of the First Amendment’,” 99 Yale L.J. 251 (1989); and Neil Hamilton, Zealotry and Academic Freedom: A Legal and Historical Perspective (New Brunswick, 1998).

Whatever the legal scope, it is clear that the First Amendment protection of individual academic freedom is not absolute. For example, in Boring v. Buncombe County Board of Education (1998), the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals held that a teacher could be reprimanded (in this case transferred) because she sponsored the performance of a play that school authorities subsequently deemed inappropriate for her students and inconsistent with the curriculum developed by the local school authorities. This judicial deference toward K through 12 institutions often can be seen in cases involving teachers who assert that their First Amendment rights were violated when school administrators imposed punishments on them for engaging—while they taught their classes—in some form of expressive activity that the administrators disapproved.

The content

While cases about academic freedom, such as Epperson, involved state laws that limited or prohibited certain content being taught (in this case prohibiting teachers in public or state-supported schools from teaching, or using textbooks that teach, human evolution); New Jersey has taken a very broad approach to classroom content. Since 1996, New Jersey has established state standards (currently called “Student Learning Standards”) that set a framework for each content area. Unlike many other states, New Jersey does not establish a state curriculum but rather leaves this to local school boards. Subject to applicable provisions of state law and standards set by the State Department of Education, district school boards have control of public elementary and secondary schools. How much protection do New Jersey teachers have when they address controversial topics? Most First Amendment education cases in New Jersey involve students’ rights rather than teachers’ rights (e.g., school dress, vulgar language, threats, religious speech, equal access, See http://www.njpsa.org/documents/pdf/lawprimer_FirstAmendment.pdf). However, several recent cases from the Third Circuit (which includes New Jersey) provide some parameters.

In Edwards v. California University of Pennsylvania (3rd Cir. 1998), a tenured professor in media studies sued the administration for violating his right to free speech by restricting his choice of classroom materials in an educational media course. Instead of using the approval syllabus, Edwards emphasized the issues of “bias, censorship, religion and humanism.” Students complained that he was promoting religious ideas in the class. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the Third Circuit’s summary judgement against Edwards, holding that a university professor does not have a First Amendment right to choose classroom materials and subjects in contravention of the University’s dictates.

A very recent decision regarding a New Jersey teacher confirms the fact that the First Amendment does not provide absolute protection for teachers in public schools to decide the content of their lessons if it is not within the curriculum set by the school district. In Ali v. Woodbridge Twp. School District (3rd Cir. April 22, 2020) a non-tenured public high school teacher at Woodbridge High School was teaching Holocaust denial to his students and was posting links to articles on the school’s website saying things such as, “The Jews are like a cancer” and expressing conspiracy theories accusing the United States of planning a 9/11-style attack. When the Board of Education fired Ali, he sued claiming that his employment was terminated on the basis of his race and religion, and that defendants had violated his rights to free speech and academic freedom, among other claims. The District Court rejected all of Ali’s claims, awarding summary judgment to the school board, and the Third Circuit affirmed.

These are extreme cases where a teacher is addressing issues that are NOT within the curriculum set by the university or within the state social studies standards and the local school district’s curriculum. When teachers are teaching a controversial topic that is included in the New Jersey Student Learning Standards for Social Studies and their school district’s social studies curriculum, the existing case law seems to support the fact that they would be protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, unless they are violating school policies that require teaching in a neutral, balanced manner that does not seek to indoctrinate students.

For example, what if a teacher wants to assign a research paper about the Stonewall Riots or the Lavender Project? Since the history of LGBT rights is in the state standards and supposed to be included in local school district social studies curriculum, the Stonewell Riots and Lavender Project would be part of this history. This is not a situation like Ali where the materials were beyond the scope of the local curriculum (as well as being taught in an indoctrinating manner—see below). If the teacher fears that the topics will be controversial with the community, he or she should make the school administration aware of what he or she is planning to do. Since here, what the teacher plans to teach is within the state standards and the local school district curriculum, the school administration should support the teacher. If parents object, the real issue is one of policy (Should LGBT history be taught?), which is decided by the state and local boards of education, not the teacher. Therefore, the parents’ argument should be with the state and local boards of education.

What if a teacher wants to show scenes of an R-rated movie in the classroom (i.e. Revolutionary War scenes from The Patriot or D-Day from Saving Private Ryan?) Obviously, the American Revolution and World War II are part of the state standards for U.S. History and in every local school district’s curriculum. The movie scenes would need to relate to the district curriculum and the teacher should get prior administrative and parental approval if some movie scenes are going to be very graphic.

How should a teacher prepare lessons on Nazi Germany during the 1930s? Nazi Germany is also part of the state history standards and every school district’s curriculum. It should be taught in a way so that students can understand how the Nazis came to power and the prejudices they carried. Some of the World War II footage and movies may be shocking but our students will not be able to become informed, engaged citizens if we hide the past from them.

An ounce of prevention beforehand will help. Before starting, teachers should be clear about the goal of their lesson: The classroom activities should encourage critical thinking. You are not trying to convince students of any particular point of view. Preview any materials, especially visual media which may be very powerful or provocative. Be aware of the biases of the sources of information that will be used by students.

Teaching Tolerance suggests in Civil Discourse in the Classroom that “Teachers can effectively use current and controversial events instruction to address a wide variety of standards and even mandated content. To do so, however, teachers must work carefully and incrementally to integrate this new approach in their classrooms.” The University of Michigan’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching offers guidance for how instructors (offered for college instructors but applicable for K-12) can successfully manage discussions on controversial topics. See Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, University of Michigan at https://crlt.umich.edu/tstrategies/tsd). The “Statement on Academic Freedom and Tenure” of the American Association of University Professors, suggests that teachers should be careful to avoid controversial matters that are unrelated to the subject discussed.

Before engaging students in an activity or discussion involving a controversial subject, tell your supervisor and/or principal what you are planning on teaching and, if necessary, reference the district policy on teaching controversial issues, explain the lesson’s connection with the district social studies curriculum and explain the goal and value of what you plan to do. Then, consider the demographics of your community. If you anticipate that the topic of your lesson will be controversial with the community, send a note and/or talk with your students’ parents and/or the Parent Teacher Organization.

In an informative piece titled “Do You Have the Right to be an Advocate?,” published by EdWeek, Julie Underwood, a professor of law and educational leadership and policy analysis at the School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison, explains that the “district or the state can regulate employee speech during school hours or at school-sponsored activities to protect their own interests in instruction and political neutrality.” Despite the ambiguity in the laws protecting a teacher’s freedom of speech, Underwood concludes: “If it relates to the in class instruction and is age appropriate there is a good rationale for having a political discussion”.

Teaching in a Neutral or Balanced Manner

If the teacher has created a supportive, respectful classroom climate and built tolerance for opposing views, it will be easier to consider controversial topics. For example, considering historical controversies might be good background as practice for looking at current controversies. Establish a process and rules of adequate evidence or support so that the discussion is based on facts rather than simply opinions. To help maintain classroom order even when students are having heated disagreements, set clear rules for discussions or use activities that require students to use active listening skills when considering controversial issues, such as:

- Continuum/Take a Stand

- Civil Conversations

- C3 Inquiries

- Guided discussions

- Socratic Smackdown

- Moot courts—structured format for considering constitutional issues

- Philosophical Chairs discussion

- Legislative hearings—structured format for considering solutions to problems

Carefully consider how students are grouped if they are to work cooperatively. Provide closure (which may be acknowledging the difficulty of the issue).

School boards work primarily through policies which set guidelines for principals, teachers, parents and students, as well as the district curriculum. To avoid a problem afterwards, the teacher should make sure that the controversial topic is within the state standards and the curriculum adopted by their local school board. Then the teacher should consult the school district’s policy regarding the teaching of controversial issues. Most school districts have a policy (usually #2240) that supports and encourages the teaching of controversial issues and sets guidelines for teaching controversial issues, including a process for dealing with challenges. Although the language may differ, policies dealing with controversial issues generally focus on the need for the classroom lesson to be balanced, unprejudiced, fair, objective, and not aimed at indoctrinating students to a particular point of view.

Clearly, the type of indoctrination attempted by the teachers in the Edwards or Ali cases is beyond protected speech. In addition to avoiding indoctrination, teachers should avoid telling a joke in the classroom that might imply a negative characterization of an ethnic group, religion or gender. A “joke” that might be a put down of any ethnic group, religion or gender told in the classroom to students is never a good idea. It is not even a good idea for a teacher to post such a “joke” on Facebook because such speech might be considered as not addressing a matter of public concern and would not be protected by the First Amendment. However, using an historical photo, engraving or picture that included a negative image of an ethnic, racial or religious group might be okay in the context of examining what was seen as humor in the past and understanding the prejudice that existed during a particular time period. For example, when teaching about the Holocaust, a teacher might carefully use Nazi cartoons to demonstrate the high level of prejudice at the time. Another example might be using images of blackface or corporate ad campaigns to show racial attitudes when teaching about Jim Crow. The teacher does not need many examples to make the point. Know your audience. Choose carefully and be aware that certain advertising images from the Jim Crow era may offend some students in the class. The purpose of using controversial issues is important. At the core of deciding what a teacher should or should not say or do in the classroom is good judgment.

Should a teacher share his or her viewpoint on a controversial issue with the students?

Whether a teacher should share his or her opinion or viewpoint on a controversial issue will depend on the age of the students, if the opinion was requested by the students, and the comfort-level of the teacher. A teacher’s opinion may have too much influence on younger students and should probably be avoided. What if a middle or high school student specifically asks for your opinion? Such “natural disclosures” in response to a direct question by a student should be accompanied by a disclaimer, such as “This is my view because…” or “Other people may have different views”. If you prefer not to disclose your view, explicitly state that and explain why. Remember, the goal is to help students develop their own well-informed positions. Be mindful of your position as the “classroom expert” and the potential impact on the students. If you decide to disclose your own view, do it carefully and only after the students have expressed their views. Unrequested disclosures may be seen as preachy, or may stop the discussion. (See Hess, Controversy in the Classroom)

So, for example, should a teacher take a position on climate change? In terms of content, climate change is in the state standards and should be in the local school curriculum. If parents disapprove of this topic, this disagreement is really with the curriculum set by the school board, not with the teacher. However, the teaching strategy is important. Rather than taking a position, which may be seen as indoctrination or may simply stop the classroom inquiry, the better approach might be to have the students examine the issue and let the facts speak for themselves. Let students use the facts that exist to construct their own arguments about whether or not climate change is the result of mankind’s use of fossil fuels in industry and transportation. If the topic is presented in a balanced, neutral, non-indoctrinating manner, the teacher should not be subject to discipline. Objections by parents should be referred to the school administration because it is a matter of policy (Should climate change be taught?), which is decided by the state and local boards of education, not the teacher.

How should teachers address questions from students regarding Black Lives Matter and racial inequality? The ACLU in the state of Washington prepared a short online article, “Free Speech Rights of Teachers in Washington State” (NJ’s ACLU only has a publication about students’ rights) with a related hypothetical: The teacher is instructed not to discuss personal opinions on political matters with students. In a classroom discussion on racial issues in America, the teacher tells the class that he/she has recently participated in a Black Lives Matter demonstration. Revealing this is the same as giving an opinion and may not be protected speech. Teachers can be disciplined for departing from the curriculum adopted by the school district and this would be a departure.

Can a teacher state that New Jersey is a segregated state when it comes to communities? Is the teacher stating this as a personal opinion or as a fact related to a topic of learning? There is no reason to simply state that NJ is segregated unless it is in the context of helping students understand and appreciate the history of segregation in NJ consistent with state standards and district curriculum. (For example, see “Land Use in NJ” and “School Desegregation and School Finance in NJ” for history, context and facts at http://civiced.rutgers.edu/njlessons.html).

Is a teacher permitted to take a stand on the issue of removing public monuments? Assuming that this is part of a current events lesson, it would be better if the teacher remained neutral and let the students’ voice differing views. If the students all have one position, perhaps the teacher can take a position as “devil’s advocate,” but it should be made clear that this is what the teacher is doing.

Can a teacher assign blame to protests to specific groups or left or right extremist groups? Assigning blame is the same as a teacher giving his or her personal opinion. The better approach would be to have students look at the actions of specific groups and determine their appropriateness.

Can a teacher assign blame to Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett regarding a Supreme Court decision that is 5-4 and against the teacher’s preference (i.e. Affordable Care Act, marriage, etc.). Assuming that this is part of a classroom lesson about the Supreme Court, the teacher should refrain from “assigning blame” because this is expressing his or her opinion, but should instead let the students consider the reasoning and impact of the decisions.

Is a teacher permitted to criticize or defend the government’s policies or actions on immigration? Outside the classroom, a teacher has a first amendment right to express his or her views on public issues. As part of a classroom lesson about immigration, rather than criticizing or defending the government’s policies or actions on immigration, the better approach would be to present or let students research the history of immigration policy and its impact and let the students discuss and draw their own conclusions (For example, see “Immigration Policy and its impact on NJ” at http://civiced.rutgers.edu/njlessons.html).

Can a teacher show a video clip from a specific news station (Fox, CNN) or assign students to watch a specific news program as an assignment? As long as the purpose is not indoctrination to any particular point of view and the assignments are balanced. If the teacher wants students to see and compare various media views on the same topic, that would be a valuable classroom activity. (For example, see “Educating for Informed, Engaged Citizens” virtual workshop, for background on helping students understand bias in news, at the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies website at http://www.njcss.org/; also see Choices Program at Brown University: Teaching with the News at https://www.choices.edu/teaching-with-the-news/; and Constitutional Rights Foundation Fake News at https://www.crf-usa.org/images/pdf/challenge/Understanding-Fake-News1.pdf and https://www.crfusa.org/images/pdf/challenge/Tackling-Fake-News.pdf).

Conclusions

A teacher has a personal right under the First Amendment to share his view on public policy issues in public but NOT in the classroom. A teacher sharing his opinion or viewpoint in the classroom may be seen as indoctrination. So, for example, teachers should avoid sharing personal views on one’s sexual preference, regarding a particular candidate, President Trump’s taxes, a decision by a Grand Jury, prosecutor, FBI on racial issues, etc. Your school district may even have an explicit policy that teachers should not discuss personal views on political matters in the classroom, in which case, this policy should be followed. Everything a teacher says or does in the classroom should be considered based on the possible impact on the students.

This does not mean that teachers should avoid having students examine and discuss controversial topics. Encouraging the development of civic skills and attitudes among young people has been an important goal of education since the start of the country. Schools are communities in which young people learn to interact, argue, and work together with others, an important foundation for future citizenship. Since the purpose of social education is to prepare students for participation in a pluralist democracy, social studies classes NEED to address controversial issues. Teachers have the right and the responsibility to help their students understand controversial topics and to develop critical thinking skills. However, the controversial topics should relate to the broad scope of subjects included in the NJ Student Learning Standards and the local school district curriculum. And controversial subjects should be addressed in a neutral or balanced manner, without any effort to indoctrinate students, but rather to help them develop the knowledge and skills they will need as workers, parents and citizens in a democratic society.

Background Materials

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923)

West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnett, 319 U.S. 624 (1943)

Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U.S. 485 (1952)

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960)

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278 (1961)

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360(1964)

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967)

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968)

Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968)

Mt. Healthy City School District Board of Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977)

Connick v. Meyers, 461 U.S. 138 (1983)

Kirkland v. Northside Independent School District, 890 F.2d 694 (5th Cir. 1989), cert. denied (1990)

Bradley v. Pittsburgh Bd. of Educ., 910 F.2d 1172 (3d Cir.1990)

Boring v. Buncombe County Board of Education, 136 F.3d 364 (4th Cir. 1998)

Edwards v. California University of Pennsylvania, 156 F.3d 488 (3rd Cir. 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1143 (1999)

Ali v. Woodbridge Twp. School District, 957 F.3d 174 (3rd Cir. April 22, 2020)

Keith Barton and Linda Levstik, Teaching History for the Common Good (Erlbaum, 2004)

Diana E. Hess, Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion (New York: Routledge, 2009)

Nel Noddings and Laurie Brooks, Teaching Controversial Issues: The Case for Critical Thinking and Moral Commitment in the Classroom (New York: Teacher’s College Press, 2017).

William W. Van Alstyne, “Academic Freedom and the First Amendment in the Supreme Court of the United States:

An Unhurried Historical Review,” 53 Law and Contemp. Probs. 79 (1990)

ACLU-Washington at https://www.aclu-wa.org/docs/free-speech-rights-public-school-teachers-washington-state

American Association of University Professors, “Academic Freedom of Professors and Institutions,” (2002) at https://www.aaup.org/issues/academic-freedom/professors-and-institutions

Center for Research on Instruction and Teaching, University of Michigan at https://crlt.umich.edu/tstrategies/tsd

Choices Program at Brown University: Teaching with the News at https://www.choices.edu/teaching-with-thenews/

Constitutional Rights Foundation at https://www.crf-usa.org/

EdSurge at https://www.edsurge.com/news/2018-01-17-why-we-need-controversy-in-our-classrooms

Facing History at https://www.facinghistory.org/educator-resources

Find Law at https://www.findlaw.com/education/teachers-rights/teachers-different-freedoms-and-rightsarticle.html

John Goodlad, “Fulfilling the Public Purpose of Schooling: Educating the Young in Support of Democracy May Be Leadership’s Highest Calling,” School Administrator, v61 n5 p14 May 2004.

Jonathan Gould, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Peter Levine, Ted McConnell, and David B. Smith, eds. “Guardian of

Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools,” Philadelphia: Annenberg Public Policy Center, 2011

Amanda Litvinov, “Forgotten Purpose: Civic Education in Public Schools, NEA Today, Mar 16, 2017 at https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/forgotten-purpose-civics-education-publicschools#

New Jersey Center for Civic Education (New Jersey lessons) at http://civiced.rutgers.edu/njlessons.html

New Jersey Law Journal at https://www.law.com/njlawjournal/2020/06/28/as-woodbridge-teachers-case-showsfacts-do-matter/?slreturn=20200929134110

New Jersey Principals and Supervisors Association at http://www.njpsa.org/documents/pdf/lawprimer_FirstAmendment.pdf

Phi Delta Kappa, “Do you have the right to be an Advocate?, at https://kappanonline.org/underwood-schooldistricts-control-teachers-classroom-speech/

Poorvu Center, Yale University at https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/teaching/ideas-teaching/teaching-controversialtopics

Teaching Tolerance at https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/publications/civil-discourse-in-theclassroom/chapter-4-teaching-controversy

Texas Association of School Boards at https://www.tasb.org/services/legal-services/tasb-school-lawesource/personnel/documents/employee_free_speech_rights.aspx

The First Amendment Encyclopedia at https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/973/rights-of-teachers U.S. Civil Liberties at https://uscivilliberties.org/themes/4571-teacher-speech-in-public-schools.html