Origin and Meaning of Critical Race Theory

Alan Singer

On a November 2021 CNN broadcast, host Chris Cuomo interviewed comedian/commentator Bill Maher about a supposed leftwing peril threatening the United States, feeding him a series of softball questions and responding with “Oh my God” facial expressions. After acknowledging “I’m not in schools” and “I have no interaction with children,” Maher announced that he has heard from people all over the country that “kids are sometimes separated into groups, oppressor and oppressed” and being taught “racism is the essence of America.” He derided this practice as “just silly, it’s just virtue-signaling” and accused people advocating for curriculum revision of being “afraid to acknowledge progress,” a psychological disorder he alternately labeled “wokeness” and “progressophobia.” Maher’s comments on “wokeness” and “progressophobia” reminded me of a 19th century medical condition described by Dr. Samuel Cartwright from Louisiana in DeBow’s Review in 1851 as “Drapetomania, the disease causing Negroes to run away from slavery.”

- https://nypost.com/2021/11/18/bill-maher-rails-against-critical-race-theory-argues-its-just-virtue-signaling/

- https://twitter.com/CuomoPrimeTime/status/1461162923259215877

I kept waiting for Chris Cuomo to ask Maher to provide an example, any example, to support his claims, but Cuomo never did and Maher never felt compelled to offer any evidence. On his television show, Maher promotes a group of contrarians that want to start their own college where they will be free to present offensive ideas and dismiss objections without having to provide supporting evidence or answer to anyone. Cuomo never asked Maher about that either.

- https://nypost.com/2021/11/18/bill-maher-rails-against-critical-race-theory-argues-its-just-virtue-signaling/

- https://twitter.com/CuomoPrimeTime/status/1461162923259215877

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t33pow_AK4E

- https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/11/17/university-austin-bari-weiss-pinker-culture-politics-522800

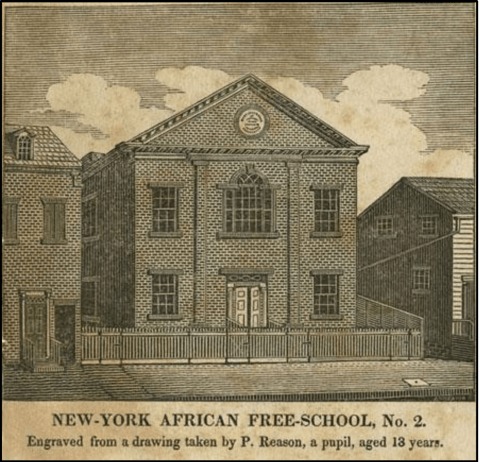

In August 2021, the Brookings Institute reported that at least eight states had passed legislation banning the teaching of Critical Race Theory, although only Idaho actually used the phrase. The modern iteration of Critical Race Theory began in the 1980s when legal scholars followed by social scientists and educational researchers employed CRT as a way of understanding the persistence of race and racism in the United States. Kimberlé Crenshaw, who teaches law at UCLA and Columbia University and was an early proponent of critical race theory, described it as “an approach to grappling with a history of white supremacy that rejects the belief that what’s in the past is in the past, and that the laws and systems that grow from that past are detached from it.” Basically, Critical Race Theory disputes the idea of colorblindness or legal neutrality and argues that race and racism have always played a major role in the formulation of American laws and the practices of American institutions. It is a study of laws and institutions that sifts through the surface cover to look for underlying meaning and motivation. In my work as a historian, I traced the current debate over “citizen’s arrest” back to its implementation in the South during the Civil War when it was used to prevent enslaved Africans from fleeing bondage. It essentially empowered any white person to seize and hold any Black person they suspected of a crime, stealing white property by stealing themselves As an academic discipline CRT does not claim that everything about the United States is racist or that all white people are racist. The CRT lens examines laws and institutions, not people, certainly not individual people.

What has come to be known as a CRT approach to understanding United States history and society actually has much deeper roots long before the 1980s. A 19th century French observer of American society, Alexis De Tocqueville, in the book Democracy in America published in 1835, wrote: “I do not believe that the white and black races will ever live in any country upon an equal footing . . . But I believe the difficulty to be still greater in the United States than elsewhere . . . [A]s long as the American democracy remains at the head of affairs . . . [I]t may be foreseen that the freer the white population of the United States becomes, the more isolated will it remain.

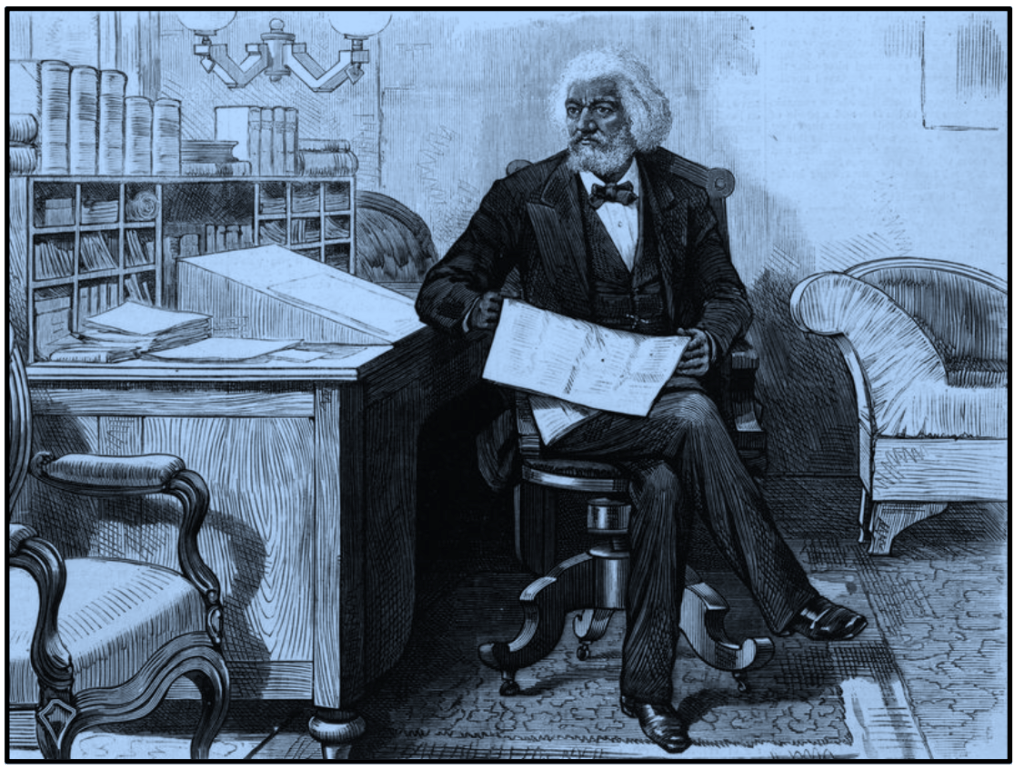

In an 1852 Independence Day speech delivered in Rochester, New York, Frederick Douglass rhetorically asked, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Douglass then answered his own question. “The blessings in which you this day rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence [given] by your fathers is shared by you, not by me . . . What to the American slave is your Fourth of July? I answer, a day that reveals to him more than all other days of the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass-fronted impudence; our shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

In the 19th century, a reverse CRT lens was openly used by racists to justify the laws and institutions derided by Alexis De Tocqueville and Frederick Douglass. In the majority opinion of the Supreme Court in its 1857 Dred Scott decision, Chief Justice Roger Taney claimed, and the Court ruled, that “A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a ‘citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States” because “When the Constitution was adopted, they were not regarded in any of the States as members of the community which constituted the State, and were not numbered among its ‘people or citizens.’ Consequently, the special rights and immunities guaranteed to citizens do not apply to them.”

The deep roots of racism were recognized by the United States Congress when it drafted the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments after the American Civil War. Abolitionist and civil rights proponent Congressman Thaddeus Stevens issued a warning in December 1865. “We have turned, or are about to turn, loose four million slaves without a hut to shelter them or a cent in their pockets. The infernal laws of slavery have prevented them from acquiring an education, understanding the common laws of contract, or of managing the ordinary business of life. This Congress is bound to provide for them until they can take care of themselves. If we do not furnish them with homesteads, and hedge them around with protective laws; if we leave them to the legislation of their late masters, we had better have left them in bondage. If we fail in this great duty now, when we have the power, we shall deserve and receive the execration of history and of all future ages.” Stevens was right. Enforcement legislation was gutted by the Supreme Court making way for Jim Crow segregation, Klan terrorism, and the disenfranchisement of Black voters for the next 100 years. The power of racism was so great that in 1903, W.E.B. DuBois wrote in the forethought to The Souls of Black Folk that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

The legal system recognizing the legitimacy of racial distinction was affirmed by the Supreme Court in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Although the Supreme Court reversed itself with the Brown v. Topeka Kansas ruling in 1954, legal action to change American society really started with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both designed to enforce the 14th Amendment prohibition that states could not make or enforce laws that “abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended in 1982, outlawed laws and practices that had the result of denying a racial or language minority an equal opportunity to participate in the political process, even if the wording of the law did not expressly mention race. A racist result was racism.

The New York State Court of Appeals also argued that under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act a law could be challenged as discriminatory if the “practice has a sufficiently adverse racial impact–in other words, whether it falls significantly more harshly on a minority racial group than on the majority . . . Proof of discriminatory effect suffices to establish liability under the regulations promulgated pursuant to Title VI.” Governments have the obligation to demonstrate that “less discriminatory alternatives” were not available. This is the modern origin of Critical Race Theory.

According to the Texas Tribune, the “new Texas law designed to limit how race-related subjects are taught in public schools comes with so little guidance, the on-the-ground application is already tying educators up in semantic knots as they try to follow the Legislature’s intent.” In one Texas district, a director of Curriculum and Instruction notified teachers that they had to provide students with “opposing” perspectives on the World War II era European Holocaust, presumably Holocaust-denial voices. It remains unclear if science teachers will now have to legitimize social media claims that the COVID-19 virus arrived on Earth from outer space.

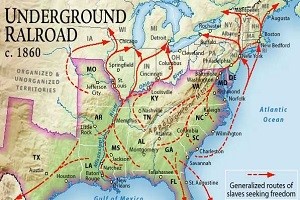

In her blog, Heather Cox Richardson, an American historian and professor of history at Boston College, focused on subjects that were crossed out of the law, which listed topics permissible to teach. The dropped topics included the history of Native Americans, the writings of founding “mothers and other founding persons,” Thomas Jefferson on religious freedom, Frederick Douglass articles in the North Star, William Still’s records for the Underground Railroad, the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, documents related to women’s suffrage and equal rights, and documents on the African American Civil Rights movement and the American labor movement, including Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” and his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech. The Texas legislature also crossed out from the list of topics that are permissible to teach the “history of white supremacy, including but not limited to the institution of slavery, the eugenics movement, and the Ku Klux Klan, and the ways in which it is morally wrong.”

What caught my attention more though was what the Texas legislators decided to include on the permissible list, documents that they apparently had never read. The “good” topics and documents include the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, the Federalist Papers “including essays 10 and 51,” excerpts from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, and the transcript of the first Lincoln-Douglas debate from 1858 when Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas ran against each other for Senator from Illinois. When you read these documents through a Critical Race Theory lens or any critical lens, they expose the depth of racism in America’s founding institutions.

The Declaration of Independence includes a passage that has stuck with me since I first read it as a high school student in the 1960s. “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” I was always impressed by the vagueness of the passage. Who has the right to abolish a government? Did they mean the majority of the people, some of the people, or did the decision have to approach near unanimity? Did enslaved Africans share this right to rebel? Very unlikely.

The words “slave” and “slavery” do not appear in the United States Constitution until passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865 that banned slavery. However, a number of clauses in the original document were intended to protect the institution. The three-fifths compromise, which refers to “other Persons,” gave extra voting strength to slave states in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College. Another clause forbade Congress from outlawing the trans-Atlantic slave trade for at least twenty years. A fugitive slave clause required that freedom-seekers who fled slavery to states where it was outlawed had to be returned to slavery if they were apprehended. The Constitution also mandates the federal government to suppress slave insurrections and the Second Amendment protected the right of slaveholders and slave patrols to be armed.

Both Federalists 38 and 54, which were most likely written by future President James Madison, himself a slaveholder, justified slavery. Madison first mentioned slavery in Federalist 38 where he defended the right of the national government to regulate American participation in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In Federalist 54, Madison explained the legitimacy of the Constitution’s three-fifths clause and of slavery itself. According to Madison, “In being compelled to labor, not for himself, but for a master; in being vendible by one master to another master; and in being subject at all times to be restrained in his liberty and chastised in his body, by the capricious will of another, the slave may appear to be degraded from the human rank, and classed with those irrational animals which fall under the legal denomination of property. In being protected, on the other hand, in his life and in his limbs, against the violence of all others, even the master of his labor and his liberty; and in being punishable himself for all violence committed against others, the slave is no less evidently regarded by the law as a member of the society, not as a part of the irrational creation; as a moral person, not as a mere article of property. The federal Constitution, therefore, decides with great propriety on the case of our slaves, when it views them in the mixed character of persons and of property.”

In the first Lincoln-Douglas debate on August 21, 1858, Stephen Douglas accused Lincoln of trying to “abolitionize” American politics and supporting a “radical” abolitionist platform. Lincoln responded that he was “misrepresented.” While Lincoln claimed to hate slavery, he did not want to “Free them, and make them politically and socially our equals? My own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not . . . We cannot, then, make them equals . . . anything that argues me into his idea of perfect social and political equality with the negro, is but a specious and fantastic arrangement of words . . . I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists.” Lincoln then added in words that show the depth of American racism, “I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality.”

The real question is why the big outrage about Critical Race Theory today? A group of traditional historians was infuriated by claims in the New York Times 1619 Project that race and racism have played a significant role in throughout American history, including as a motivation for the War for Independence. Whatever you think about that claim in the 1619 Project, I don’t think anyone seriously believes that opposition by a small group of historians is the basis for the assault on CRT. The much-criticized opening essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones does not even mention Critical Race Theory.

I believe the public attacks on Critical Race Theory, including in school board meetings, are a rightwing response to challenges to police actions following the murder of George Floyd and to the Black Lives Matter movement’s demands for racial justice. They have nothing to do with what or how we teach.

CRT became controversial when President Trump denounced it in an effort to rally his supporters during his re-election campaign. Trump declared, without any evidence, that “Critical race theory is being forced into our children’s schools, it’s being imposed into workplace trainings, and it’s being deployed to rip apart friends, neighbors and families.” According to Professor Crenshaw, acknowledging racism was being defined by President Trump and his supporters as racism. Racial equity laws and programs were called “aggression and discrimination against white people.”

We don’t teach CRT in the Pre-K to 12 curriculum because we don’t teach theory. We certainly don’t teach children to hate themselves or this country. What we do teach is critical thinking, and a critical race theory approach is definitely part of critical thinking.

Critical thinking means asking questions about text and events and evaluating evidence. It is at the core of Common Core and social studies education. I like to cite the conservative faction of the Supreme Court that claims to be “textualists,” meaning they carefully examine the text of laws to discover their meaning. Because they will need to become active citizens defending and extending democracy in the United States, we want young people to become “textualists,” to question, to challenge, to weigh different views, to evaluate evidence, as they formulate their own ideas about America’s past, the state of the nation today, and the world they would like to see.

The Texas anti-CRT law also includes more traditional social studies goals, “the ability to: (A) analyze and determine the reliability of information sources; (B) formulate and articulate reasoned positions; (C) understand the manner in which local, state, and federal government works and operates through the use of simulations and models of governmental and democratic processes; (D) actively listen and engage in civil discourse, including discourse with those with different viewpoints; (E) responsibly participate as a citizen in a constitutional democracy; and (F) effectively engage with governmental institutions at the local, state, and federal levels.” It also includes an appreciation of “(A) the importance and responsibility of participating in civic life; (B) a commitment to the United States and its form of government; and (C) a commitment to free speech and civil discourse.”

Given these very clearly stated civics goals, I recommend that Texas social studies teachers obey the civics legal mandate by organizing with their students a mass campaign to challenge restrictions in the Texas law, including classroom “civil disobedience” by reading the material that was crossed out of the law. Maybe someday Texas students can share Martin Luther King’s “dream.”

AIM: How enlightened was the European Enlightenment? A CRT Lens Lesson

This lesson on the European Enlightenment is for the high school World History curriculum. The European Enlightenment is one of the first topics explored in the New York state 10th grade social studies curriculum. This lesson uses a CRT lens to build on understandings about the Scientific Revolution and the trans-Atlantic slave trade that were studied in the 9th grade. It establishes themes that reemerge in units on European Imperialism in Africa and Asia and lessons on Social Darwinism. Many scholars credit the European Enlightenment with establishing modern ideas like liberty and democracy. But it also defended gender inequality and attempted to establish a scientific basis for racism. Students are asked to take a closer look and decide: “How enlightened was the European Enlightenment?”

Do Now: The European Enlightenment is often known as the Age of Reason because Enlightenment thinkers tried to apply scientific principles to understand human behavior and how societies work. Many of the earliest Enlightenment thinkers were from England, Scotland, and France but the idea of using reason and a scientific approach spread to other European countries and their colonies. In the United States, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin are considered Enlightenment thinkers. While there are no firm dates, most historians argue that the European Enlightenment started in the mid-17th century building on the Scientific Revolution, and continued until the mid-19th century. Some historians have pointed out that the Age of Reason in Europe was also the peak years of the trans-Atlantic slave trade when millions of Africans were transported to the Americas as unfree labor on plantations.

One of the first major European Enlightenment thinkers was John Locke of England. Read the excerpt from Locke’s Second Treatise on Civil Government, written in 1690, and answer questions 1-4.

| John Locke: “Liberty is to be free from restraint and violence from others . . . Good and evil, reward and punishment, are the only motives to a rational creature: these are the spur and reins whereby all mankind are set on work, and guided . . . Man . . . hath by nature a power . . . to preserve his property – that is, his life, liberty, and estate – against the injuries and attempts of other men . . . The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom . . . All mankind . . . being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions.” |

Questions

- According to Locke, what is the most important human value?

- How does Locke believe this value is preserved?

- What document in United States history draws from Locke? Why do you select that document?

- In your opinion, why is John Locke considered a European Enlightenment thinker?

Activity: You will work with a team analyzing a quote from one of these European Enlightenment thinkers and answer the following questions. Select a representative to present your views to class. After presentations and discussion, you will complete an exit ticket answering the question, “How enlightened was the European Enlightenment?”

Questions

- Where is the author from? What year did they write this piece?

- What is the main topic of the excerpt?

- What does the author argue about the topic?

- Why is this author considered a European Enlightenment thinker?

- In your opinion, what do we learn about the European Enlightenment from this except?

| David Hume (Scotland, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, 1779): “What truth so obvious, so certain, as the being of a God, which the most ignorant ages have acknowledged, for which the most refined geniuses have ambitiously striven to produce new proofs and arguments? What truth so important as this, which is the ground of all our hopes, the surest foundation of morality, the firmest support of society, and the only principle which ought never to be a moment absent from our thoughts and meditations? . . . Throw several pieces of steel together, without shape or form; they will never arrange themselves so as to compose a watch. Stone, and mortar, and wood, without an architect, never erect a house.” |

| Baron de Montesquieu (France, The Spirit of the Laws, 1748): “Political liberty in a citizen is that tranquility of spirit which comes from the opinion each one has of his security, and in order for him to have this liberty the government must be such that one citizen cannot fear another citizen. When the legislative power is united with the executive power in a single person or in a single body of the magistracy, there is no liberty, because one can fear that the same monarch or senate that makes tyrannical laws will execute them tyrannically. Nor is there liberty if the power of judging is not separate from legislative power and from executive power. If it were joined to legislative power, the power over life and liberty of the citizens would be arbitrary, for the judge would be the legislator. If it were joined to executive power, the judge could have the force of an oppressor. All would be lost if the same man or the same body of principal men, either of nobles or of the people exercised these three powers: that of making the laws, that of executing public resolutions, and that of judging the crimes or disputes of individuals.” |

| Marquis de Lafayette (France, The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, 1789): “Therefore the National Assembly recognizes and proclaims, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following rights of man and of the citizen: Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.” |

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau (France, Emile, or Education, 1762): “Women have ready tongues; they talk earlier, more easily, and more pleasantly than men. They are also said to talk more; this may be true, but I am prepared to reckon it to their credit; eyes and mouth are equally busy and for the same cause. A man says what he knows, a woman says what will please; the one needs knowledge, the other taste; utility should be the man’s object; the woman speaks to give pleasure. There should be nothing in common but truth . . . The earliest education is most important and it undoubtedly is woman’s work. If the author of nature had meant to assign it to men he would have given them milk to feed the child. Address your treatises on education to the women, for not only are they able to watch over it more closely than men, not only is their influence always predominant in education, its success concerns them more nearly, for most widows are at the mercy of their children, who show them very plainly whether their education was good or bad.” |

| Mary Wollstonecraft (England, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792): “Till women are more rationally educated, the progress in human virtue and improvement in knowledge must receive continual checks . . . The divine right of husbands, like the divine right of kings, may, it is to be hoped, in this enlightened age, be contested without danger . . . It would be an endless task to trace the variety of meannesses, cares, and sorrows, into which women are plunged by the prevailing opinion that they were created rather to feel than reason, and that all the power they obtain, must be obtained by their charms and weakness . . . It is justice, not charity, that is wanting in the world. . . . How many women thus waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practiced as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to which it at first gave lustre.” |

| Immanuel Kant (Germany, 1761, quoted in Achieving Our Humanity): “All inhabitants of the hottest zones are, without exceptions, idle . . . In the hot countries the human being matures earlier in all ways but does not reach the perfection of the temperate zones. Humanity exists in its greatest perfection in the white race. The yellow Indians have a smaller amount of Talent. The Negroes are lower and the lowest are a part of the American peoples . . . The race of the Negroes, one could say, is completely the opposite of the Americans; they are full of affect and passion, very lively, talkative and vain. They can be educated but only as servants (slaves), that is they allow themselves to be trained. They have many motivating forces, are also sensitive, are afraid of blows and do much out of a sense of honor.” |

| Thomas Jefferson (British North America, Preamble, Declaration of Independence, 1776): “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” |

| Thomas Jefferson (Virginia, Notes on the State of Virginia, 1785): “The first difference which strikes us is that of colour. Whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarf-skin, or in the scarf-skin itself; whether it proceeds from the colour of the blood, the colour of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and cause were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races? Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions of every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immovable veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race? . . . Their griefs are transient. Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them. In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection . . . Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous.” |

Exit ticket: “In your opinion, how enlightened was the European Enlightenment?”

What did Thomas Jefferson Buy in October 1803?

The Louisiana Purchase is generally presented to students as a land deal between the United States and France. Napoleon’s hope for a French New World empire collapsed when formerly enslaved Africans on the western third of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola defeated French forces and established an independent republic. The United States was anxious to purchase the French port of New Orleans near the mouth of the Mississippi River to open up the river to U.S. settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains. Napoleon made a counter-offer and for $15 million the U.S. acquired over 800,000 square miles of land stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. Or did it?

In middle school, students generally trace the expansion of American territory on maps and may read a biography of explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their First Nation guide and translator Sacagawea. Sacagawea was a Shoshone woman who had been kidnapped by another tribe. At the time of the expedition, she was married to a French fur-trapper and pregnant. Her baby, a son, was born during the expedition.

In high school students often examine the constitutional debate surrounding the purchase. President Thomas Jefferson was generally a strict constructionist who believed in limited federal authority. Although the Constitution did not expressly authorize the federal government to purchase territory, Jefferson and his special envoy James Monroe argued it was permissible under the government’s power to negotiate treaties with foreign powers. Parts or all of the present day states of Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Minnesota, New Mexico, Texas, and Louisiana, were acquired by the United States.

However, despite claims to the territory between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains by both Spain and France, there were very few European settlers in the region outside of the area near New Orleans where the non-native population was about 60,000 people, including 30,000 enslaved Africans. During the expedition west, Lewis, Clark, and Sacagawea encountered members of at least fifty different Native American tribes, some of whom had never met Europeans before, most of whom had never heard of France or Spain, and none of whom recognized Spanish, French, or American sovereignty over their homelands. The Native American population of the region included the Quapaw and Caddo in Louisiana itself, and the Shoshone, Pawnee, Osages, Witchitas, Kiowas, Cheyenne, Crow, Mandan, Minitari, Blackfeet, Chinook, and different branches of the Sioux on the Great Plains.

The reality is that for $15 million the United States purchased French claims to land that belonged to other people and was not France’s to sell and then used military force to drive the First Nations into restricted areas and instituted policies designed to destroy their cultures. Middle school students should consider how they would you feel if someone from someplace else who they had never met knocked on their door and told their family that they all had to leave because a King across the ocean or a President thousands of miles away gave them ownership over their house and the land it stood on? High school students should discuss whether Manifest Destiny, American expansion west to the Pacific, was a form of imperialism, and how it was similar or different from European colonization in the Americas, Africa, and Asia? High school students should also discuss whether United States treatment of the First Nations constitutes genocide and what would be an appropriate recompense for centuries of abuse.

As many areas of the United States shift from celebrating Columbus Day to Indigenous People’s Day, a good question to start with is to ask students exactly what did Thomas Jefferson buy in October 1803?