Museums in New York and New Jersey

New York and New Jersey are home to many historical landmarks and sites, some better known than others. Below are several such sites which may not be as familiar to teachers and students.

Raynham Hall Museum

30 West Main Street

Oyster Bay, NY 11771

Video tour: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tSZVM6-qEbw

In 1740, 23-year-old Samuel Townsend purchased the property now known as Raynham Hall, moving from his father’s place in nearby Jericho. His move to Oyster Bay allowed him easier access to the waterfront and benefited his growing shipping business, co-owned with his brother, Jacob, who moved in next door on Main Street. Samuel’s property consisted originally of a four-room frame house on a sizable plot of land, with an apple orchard across the street, hundreds of acres of nearby pasture and woodlands for his livestock, and a meadow leading down to the harbor, where he and Jacob kept their ships.

In short order, Samuel had enlarged the house to eight rooms by building a lean-to addition on the north side, creating a saltbox-style house. This property, then known simply as “The Homestead,” would have been a hub of activity during the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, and was home to Samuel, his wife Sarah Stoddard Townsend, their eight children, and 20 enslaved people.

By 1769, Samuel and his brother Jacob owned five ships, which sailed to Europe, Central America, and the West Indies. They traded in an impressive range of goods, including most importantly logwood (which was and continues today to be a crucial ingredient in the dyeing of textiles), tea, lumber, molasses, sugar, china, wine, textiles, dye and rum. In addition to the shipping business, Samuel operated a general store, providing local access to a wide variety of imported wares. He was an active member of local and state government, as Oyster Bay’s Justice of the Peace and Town Clerk, a member of the New York Provincial Congress from 1774 to 1777, and, after the Revolution, a New York State Senator from 1786 to 1790.

Although most of Oyster Bay sided with the British during the American Revolution, Samuel’s sympathies were with the Patriots, despite the far greater risks those sympathies posed to his position, family and fortune. Following the Patriots’ decisive defeat in 1776 at the Battle of Long Island, British forces occupied all of New York City and Long Island, often brutally. Many people in the area who ran afoul of British authorities were confined to prison ships on which more than 12,000 people would die of illness or starvation by the end of the war in 1783, at a time when Manhattan’s entire population was around 20,000. The Townsend family, unlike many Patriots who fled, decided to stay in their home throughout the occupation.

Typical of wealthy New York families, the Townsends of Raynham Hall held many enslaved people who labored to maintain the house and grounds, the livestock and the fields, as well as possibly working on the Townsends’ ships. Samuel Townsend’s business interests also were intertwined with the economics of slavery, including, as they did, trade in such products as logwood, sugar, rum and tobacco.

The earliest slave record concerning the Townsends is a receipt of the purchase of a man bought by Samuel in 1749 for 37 pounds. No name is listed on the receipt. A Bible in Raynham Hall Museum’s collection contains entries from 1769 to 1795 recording the names, births and deaths of seventeen people held enslaved by the Townsends, as well as a partial genealogy. The record lists first names only, including Hannah, Violet, Susannah, Jeffrey, Susan, Catherine, Lilly, Harry, Gabriel and Jane. When the oldest Townsend son, Solomon, married his cousin Anne in 1782, they were given two people, Gabriel and Jane, as wedding presents. Gabriel and Jane’s children, Nancy, Kate, Jim and Josh, also became enslaved to Solomon, as did several others not listed in the Bible, named Charles, Shadwick, Pricilla, and her unnamed son. Additionally, letters show Samuel also owned a young woman named Elizabeth, who escaped Oyster Bay with the British Queen’s Rangers when they decamped in 1779. Samuel’s daughter Audrey and her husband Capt. James Farley owned a woman named Rachel Parker, and Audrey’s sister Phebe’s husband Ebenezer Seeley held a man named Amos Burling as his property. Interestingly, Robert Townsend was a member of the New York Manumission Society, founded in 1785, which worked towards the abolition of slavery.

Other enslaved people from the Oyster Bay area are recorded as having come to the Townsends’ store to purchase goods for their masters or for themselves, and a ledger now in the collection of the New-York Historical Society, but kept back in the day by sons William and David, records many purchases made during the 1760s and 1770s. In 2015, Raynham Hall Museum’s historian Claire Bellerjeau discovered a document at the New-York Historical Society that was revealed to be the sixth known poem by Jupiter Hammon, the first published African-American author in America, also an enslaved person owned by the Lloyds of Lloyd Harbor.

In September of 1776, British soldiers came to Samuel Townsend’s home in Oyster Bay to arrest him for his outspoken Patriotic beliefs, and to imprison him on one of the notorious prison ships in New York Harbor, where horrendous conditions would result in the deaths of over 12,000 captives by the end of the war. According to the recollection of family members, a British officer in the home smashed a hunting rifle that was mounted above the mantle, declaring that a rebel had no right to possess such a weapon, and then motioned to a portrait of the Townsends’ oldest son, Solomon, demanding to see him as well. When told that Solomon was at sea, he expressed regret that they could not arrest him as well. Outside the house, wife Sarah and daughters Sally and Phebe were frantic, afraid they might never see Samuel again.

Samuel was led away through the village and towards Jericho, traveling up the long hill in Pine Hollow. Coming down the hill in the opposite direction were Thomas Buchanan and his wife Almy, Samuel’s brother Jacob’s daughter, riding in a Phaeton carriage, with Samuel’s daughter Audrey alongside on horseback. Though he was considered a Tory, Buchanan was very close to the Townsends. He was also in the shipping business with the Townsends and had hired Samuel’s oldest son Solomon to captain his merchant ship, the Glasgow.

According to family history, when Buchanan saw Samuel being led away, he took Audrey’s horse and followed the soldiers to Jericho, where he paid a huge sum of money — several thousand pounds — to secure Samuel’s freedom. To the great relief of family and friends in Oyster Bay, Samuel returned home, unharmed, though he was then compelled to sign an oath of allegiance to the king, foreclosing any overt action against the crown. Following the end of the war in 1783, when all British were required to evacuate, Thomas Buchanan’s great loyalty and friendship were remembered, and he was allowed to stay and continue his successful merchant business in New York, unlike many Loyalists who were forced to emigrate, forfeiting their property.

For a six-month period from 1778 to 1779, the Townsend home served as headquarters for a regiment of over 300 British troops called the Queen’s Rangers, and their commander, Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe, who quartered himself in the house, alongside the family. Daily officers’ meetings were held in the front parlor, and the presence of British officers in the house became an everyday fact of life. In March of 1779, Simcoe was visited for several weeks by a close friend, British officer and intelligence chief Maj. John André, who would later be hanged as a spy for his role in helping Benedict Arnold turn traitor in 1780. André, by all accounts a remarkable charismatic person, and an accomplished amateur artist, was 29 years old at the time of his death. After the war, Lt. Col. Simcoe founded the city of Toronto, where he served as Governor of Upper Canada.

At the time he accepted to join George Washington’s intelligence network in 1779, Robert Townsend operated a Manhattan-based merchant shipping firm with his brother William and cousin John. Using his work as a merchant as a cover, Robert could move about the coffee houses, social events, shops and docks of Manhattan, eavesdropping and observing British troop movements, without arousing suspicion.

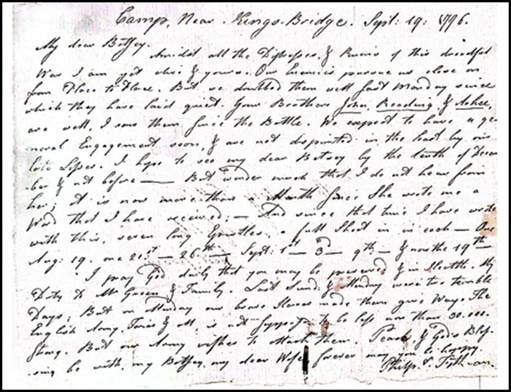

Under the code name “Culper Junior,” Robert formed the first link in a chain of agents who came to be known as the Culper Spy Ring. Using a special invisible ink formula, invented by John Jay’s brother Sir James Jay, as well as an elaborate numeric code, the spies supplied Washington with critical information about New York City and Long Island.

Robert Townsend served his country well, and at great risk to himself and his family. Though he moved back to Raynham Hall following his father’s death in 1790 and lived for years with his sisters Sarah and Phebe, he kept his involvement in the Culper Spy Ring a total secret from his family and friends for the remainder of his life. Indeed, Robert’s involvement in the Culper Spy Ring was not uncovered until the 1930s, when historian Morton Pennypacker hired a well-known handwriting analyst to prove the true identity of Culper Junior.

Liberty Hall at Kean College

1003 Morris Avenue

Union, NJ 07083

In 1760, when lawyer William Livingston, a member of the prominent Livingston family, was planning to build a country home, he bought 120 acres in what was then sleepy bucolic Elizabethtown, New Jersey, just across the river from his New York home. For the next twelve years, Livingston developed the extensive grounds, gardens and orchards. and oversaw the building of a beautiful fourteen-room Georgian-style home. In 1774, Livingston and his wife, the former Susannah French of New Brunswick, moved to Liberty Hall on a full-time basis with their children and the several people he and his family enslaved. The peace and quiet Livingston sought was short-lived. From 1774 to 1776, Livingston put his retirement on hold and served as a member of the First and Second Continental Congress and as Brigadier General of the New Jersey militia. On August 31, 1776, Livingston became New Jersey’s first elected governor. The ensuing war years were difficult ones for the governor, who spent them on the run from British troops. Finally, after the war in 1783, he was able to return to his home, which was heavily damaged by both British and American troops. Livingston also signed the United States Constitution, in addition to chairing two major committees at the Constitutional Convention. While juggling the demands of governing, Livingston also managed to pursue his great love of gardening and agriculture, utilizing the labor of free and enslaved individuals. Governor Livingston served as governor for fourteen years until his death on July 25, 1790. He is credited with making the New Jersey governorship one of the strongest.

At Liberty Hall, our goal is to deepen our visitors’ understanding of history and nature through the lens of the people who lived and worked in our over 250-year history. We strive to engage with our broader community by providing entertaining and educational programming that will inspire curiosity about the world around them and how that world has changed over time.

Liberty Hall stands at the center of the American Revolution and academic excellence. Home to trailblazing governors, congressmen, senators, assembly persons, philanthropists, and entrepreneurs, its plush gardens have spurred civic change and social innovation for centuries. Inhabited by William Livingston, New Jersey’s first elected governor and a signer of the United States Constitution, the 14-room Georgian-style home evolved over time into a 50-room Victorian mansion.

Liberty Hall began welcoming the public to experience its history and participate in its future in the year 2000. The museum has hosted educational programs, community events, civic ceremonies, and holiday celebrations.

The site is not just home to the stories of public servants and bold industrialists, its magnificent grounds also include an elegant English parterre garden and maze. Visit to view the scenery or explore the collections of antique furniture and decorative artifacts collected by the seven generations, including both the Livingston and Kean families, who called Liberty Hall home.

Macculloch Hall Historical Museum

45 Macculloch Ave. Morristown, NJ 07960

Newly arrived British immigrants George and Louisa Macculloch built Macculloch Hall in 1810. They expanded their Federal-style mansion in 1812 and 1819, tripling its size, as their family’s prominence in local, state, and national affairs grew. Come explore the largest collection of original work of political cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840-1902), art, and American history where it happened.

In 1810 George and Louisa Macculloch purchased a 26-acre parcel of land on which they built Macculloch Hall. The Maccullochs cultivated the land primarily to feed their family, planting a traditional kitchen garden as well as apple and pear orchards. George Macculloch (1775-1858) loved the gardens and kept meticulous journals. From them we know what was planted when and where, how crops did and what the family ate. Some of Louisa Macculloch’s (1785-1863) recipes are among the family’s papers in the Museum’s Archives. Modern adaptations of many of them are under “Interactive Activities.”

In the span of five generations, the Macculloch/Miller/Post family members went from owning enslaved men, women, and children to donating land for one of Morristown’s first Black churches, to speaking out on the national stage against the expansion of slavery, to commanding Civil War African American soldiers, and to raising money to support an African American industrial school in Georgia—all while the family lived at Macculloch Hall. George and Louisa Macculloch arrived in Morristown in 1810 with their daughter Mary Louisa and son Francis. They also brought with them three enslaved adults: Cato, Susan, and Betty, as well as a toddler, Emma. Since no legal requirements existed to record slave sales, it is not known when or where George purchased them. The Morris County manumission records have not survived, so there is no record of their being freed.

We know from the family Bible the names of the children born into slavery at Macculloch Hall: William (1811), Henry (1814), and Helen (1817). Their Bible does not name the parents. However, there is some additional information in birth certificates filed with the county clerk. This registration was required by the 1804 Gradual Emancipation Act. On January 8, 1812, George Macculloch registered the births of Emma “on or about September 1809, mother Susan”, and William “April 18, 1811, mother Susan”. No record is noted about the father. It also seems that Henry and Helen’s birth were not registered.

Very little is known about the enslaved men, women, and children at Macculloch Hall. With one exception, they are not mentioned in the surviving archive of family letters and documents. Although not mentioned, we know that their forced servitude, together with the paid labor of men and women in the area, enabled the Maccullochs to run their house and farm. Mary Louisa Macculloch Miller (1804-1888), George and Louisa’s daughter, spent her entire life at Macculloch Hall. She and her husband Senator Jacob Miller raised their nine children there. The fact that her family had owned enslaved men, women, and children and that Mary Louisa grew up in a house with enslaved servants, did not preclude her from supporting the African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the first independent Black churches in Morristown.

Jacob W. Miller (1800-1862), a lawyer from Long Valley, N.J., married Mary Louisa Macculloch in 1825. In 1838 he was sent to the New Jersey Legislature and was elected to the U.S Senate in 1840 where he served two terms as a member of the Whig party. After his defeat in 1852, he joined the newly formed Republican party. Although never a full-fledged abolitionist, he remained a staunch supporter of the Union and was opposed to the extension of slavery into the territories. Views he shared in common with Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s. His feelings on the burning issues of the day were expressed in speeches he delivered on the annexation of Texas, the Mexican War, the Wilmot Proviso, and the Compromise of 1850.

On May 23, 1844, Miller delivered a speech in the Senate opposing the annexation of Texas because it would give an advantage to the slave states. He also saw a danger in the Mexican War arguing that President Polk’s…” conquered peace in Mexico will become the fierce spirit of discord at home.” Following the end of the war in 1846, he supported the Wilmont Proviso that would have prohibited slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico. This proposal never passed into law.

In 1850, Henry Clay attempted to seek a compromise and avert a crisis between North and South on the issue of slavery. Senator Miller opposed the combination of Clay’s recommendations into a single Omnibus bill, but he did support several of these measures when split into separate bills. His speeches on these matters reveals the complex nature of his views on slavery and emancipation reflecting the fact that many anti-slavery advocates opposed the western expansion of slavery, but had little interest in the fate of enslaved people in the South. Miller voted to admit California as a free state, abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, and prohibit slavery in Utah and New Mexico. The results were mixed. California was admitted, Utah and New Mexico could be organized with no restrictions on slavery, and in the District of Columbia slavery was permitted, but the slave trade was outlawed.

In the vote on the Fugitive Slave Act, Miller abstained. However, in the debates he revealed what many of his fellow New Jerseyans thought about the plight of the runaways by stating:

Macculloch Hall Historical Museum’s Historic Archives contain materials from five generations of the descendants of George (1775-1858) and Louisa (1785-1863) Macculloch, United States Senator Jacob Welch Miller (1800-1862), political cartoonist and illustrator Thomas Nast (1840-1902), and museum founder W. Parsons Todd (1877-1976). Garden highlights include the wisteria trellised along the rear porch, given to the Maccullochs by Commodore Matthew Perry in 1857; the sundial on the upper lawn installed in 1876; the sassafras tree at the far end of the lawn, believed to be the second oldest and largest sassafras tree in New Jersey; and many varieties of heirloom roses, meaning their cultivars date to before 1920. Mrs. Macculloch paid Francis Cook $1.00 to plant the first roses in 1810.