African American & Labor History Timeline

Prepared by the Queens, New York Public Library and the University of Minnesota, Carlson School of Management

Every facet of the United States has been affected by the labor and inventions of African Americans. Discover some of the men and women who created the inventions that improved daily life, fought for fair wages, safety, equal rights, and justice for Black workers. These are just some of the important milestones in the history of Black Labor in America. To learn more, visit your local library during Black History Month—and beyond!

1500s-1865: Transatlantic Slave Trade through the American Civil War

1500s: Transatlantic Slave Trade

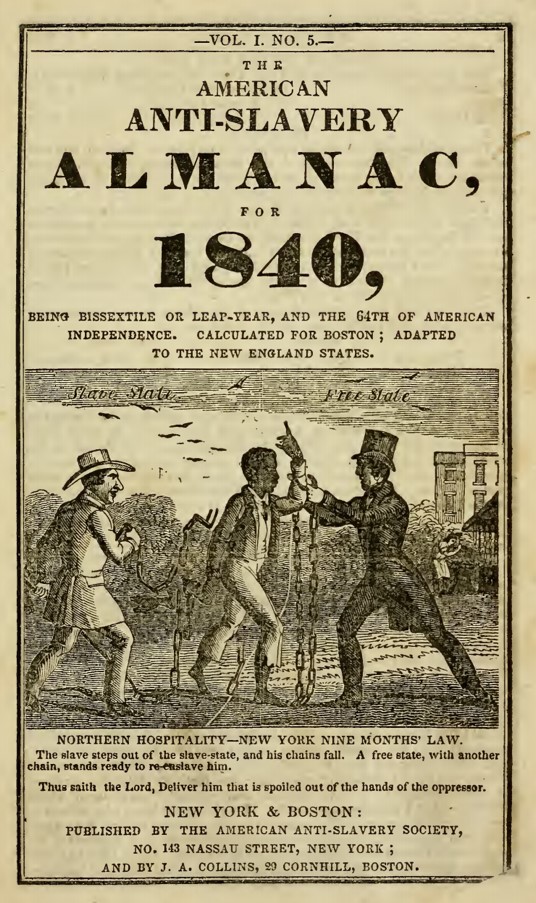

The largest oceanic forced migration in history, the Transatlantic Slave Trade began in the late 1500s when over 12.5 million African men, women and children were removed from the continent and transported to the Americas, Brazil and the Caribbean to work on plantations and live their lives in servitude. As a result, many slave rebellions erupted throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, constituting some of the first organizing and labor-related actions in the Americas.

1739: Traditional African drumming is banned

Enslaved Africans were prohibited from playing traditional drums, as European enslavers feared that drumming could facilitate communication across fields, uplift weary spirits, comment on oppressive masters, and incite rebellions. In response, Black people developed alternative forms of musical expression, such as hand clapping and percussive stomping, which became the foundation of work songs and spirituals. These musical forms later evolved into genres like the blues and jazz and are integral to today’s African American music.

c.1763-c.1826: Artist Joshua Johnson

Recognized as one of the earliest professional African American artists, Johnson was born into slavery near Baltimore around 1763 and gained his freedom in 1782. He described himself as a “self-taught genius” and painted portraits of families, children, and prominent residents of Maryland.

1786: The Tignon Law

This Louisiana law was enacted to regulate the appearance of free women of color to “establish public order and proper standards of morality,” and subjection to undesirability. Women were prohibited from going outdoors without wrapping their natural hair with a Tignon cloth. As a symbol of rebellion, Black women reappropriated Tignon production into a major fashion statement, form of self-expression and business by embellishing the headscarves with decorative fabrics, feathers and jewels.

1859: Author Harriet E. Wilson

Our Nig; or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black is considered the first novel by an African American woman. It gave insight into the supposed “Free North,” challenging the idea that the North was a safe have providing peace and equality for African Americans

1865: 13th Amendment Outlaws Slavery

The official end to slavery was perhaps the greatest labor victory in U.S. history. Yet the struggle for equal rights and fair wages was far from over; the same year that Congress adopted the 13th Amendment, the white supremacist terrorist organization and hate group, the Ku Klux Klan, was formed.

1865-1900: Reconstruction and the Gilded Age

1865-1877: Reconstruction

In the decade following the Civil War, Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau to help African Americans with food, housing, education, political rights and negotiating labor agreements. This period is thought to be one of expanding freedom for the formerly enslaved but in the South they were subjected to violence and new forms of mistreatment.

1872: Frederick Douglass

Douglass was elected president of the “Colored” National Labor Union, and his The New National Era became the union’s official newspaper. Douglass was one of America’s most important champions of equality and the right to organize a union.

1880s: Knights of Labor

The St. Paul Minnesota Trades & Labor Assembly was founded with the assistance of the Knights of Labor Assembly in1883. The Knights of Labor were known for their inclusiveness for accepting women and African American members, however they also supported the Chinese Exclusion Act.

1883: Lucy Parsons (c. 1851 – 1942)

Lucy Parsons and her husband, Albert Parsons, a former Confederate soldier turned anarchist, founded the International Working People’s Association. In 1886, they led the city’s first May Day parade, which called for an eight-hour workday.

1900s-1950s

1901: Up from Slavery

Booker T. Washington, a major voice for economic self-reliance and racial uplift, publishes his autobiography discussing his life and thoughts on race relations.

1905-1960: The Great Migration

In the first half of the 20th century, a mass migration of more than six million Black people took place from the South to the North. Many left to escape overt Southern racism, only to encounter racial tensions in the North as whites viewed them as a threat to their jobs. The Migration Series is a group of paintings by African American painter Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) which depicts the migration of African Americans to the Northern U.S. from the South. It was completed in 1941 and was conceived as a single work rather than individual paintings. Lawrence wrote captions for each of the sixty paintings. Viewed in its entirety, the series creates a narrative in images and words that tells the story of the Great Migration.

1909: National Training School for Women and Girls

Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879-1961) was a suffragist, educator and organizer, as well as a mentor to the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who worked to integrate labor reform into the movement for voting rights. Burroughs established the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1909 to combat labor exploitation through education, helping to improve working conditions and expand career pathways for Black women. She also launched the National Association of Wage Earners in 1921, a labor union for Black domestic workers.

1910s-1930s: The Harlem Renaissance

A period of flourishing of African American art, literature, and performance art saw the rise of iconic figures like author Langston Hughes, trumpeter Louis Armstrong, pianist Duke Ellington, and vocalists Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. Langston Hughes was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance. A major poet, Hughes also wrote novels, short stories, essays, and plays.

1910: The Foster Photoplay Company

William D. Foster founds the first film production company established by an African American. It features all African American casts. The Railroad Porter (circa 1913) was the first film produced and directed by an African American.

1917: East St. Louis Race Riot

During World War I, thousands of Blacks moved to the St. Louis area to work in factories fueling the war effort. When the largely white workforce at the Aluminum Ore Company went on strike, hundreds of Blacks were hired as strikebreakers. Tensions erupted, and thousands of whites, many of them union members, attacked African Americans and set fire to their homes. Between 100 and 200 Blacks are estimated to have been killed and were 6,000 left homeless.

1919: Red Summer

Racial tensions were inflamed during the September 1919 Steel Strike, when workers shut down half of the nation’s steel production in an effort to form a union. Bosses replaced them with some 40,000 African American and Mexican American strikebreakers, an action made possible by AFL unions that excluded people of color from union jobs and membership.

1921: Tulsa Race Massacre (May 31-June 1, 1921)

The Tulsa Race Massacre was a 1921 attack on Tulsa’s Greenwood District, an affluent African American community whose thriving business and residential areas were known as “Black Wall Street.” In response to a May 31 newspaper report of alleged black-on-white crime, white rioters looted and burned Greenwood in the early hours of June 1. The governor of Oklahoma declared martial law, and National Guard troops arrived and detained all Black Tulsans not already interned. About 6,000 Black people were imprisoned, some for as long as eight days. In the end, 35 city blocks lay in ruins, more than 800 people were injured, and as many as 300 people may have died. The Massacre was largely omitted from local, state, and national histories until the Tulsa Race Massacre Commission convened in 1997 to investigate the event. Today, memorials, historical exhibits, and documentaries are some of the ways that the Massacre has been acknowledged and the history of “Black Wall Street” kept alive.

1925: Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

The first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor. African American porters performed essential passenger services on the railroads’ Pullman sleeper cars and the union played a key role in promoting their rights. In the summer of 1925, A. Philip Randolph (1889-1979) met with porters from the Chicago-based Pullman Palace Car Company. The mostly Black Pullman workforce were paid lower wages than white railway workers and faced harsh conditions and long working hours. Randolph worked with these workers to form and organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. When the union was finally recognized in 1935, it became the first predominantly Black labor union in the nation. As the union’s founder and first president, A. Philip Randolph became a leader in the Civil Rights Movement.

1930s: The Great Depression

African Americans primarily worked as sharecroppers on white-owned land, and tenant farmers in the south. They continued migrating to the north in search of better opportunities, but due to racism, they often found work as domestics, in factories, and as seasonal traveling migrant farmers. New Deal programs provided some relief, but they still faced unequal access to programs like the Works Progress Administration due to racial segregation and violence.

1934: Dora Lee Jones (1890-1972)

Jones helped found the Domestic Workers Union (DWU) in Harlem in 1934 in defiance of New York City’s “slave markets,” as they were known. With few options during the Depression, Black women would gather daily in the morning at certain locations and wait for white middle-class women to hire them, typically for low wages. The DWU eventually affiliated with the predecessor to today’s Service Employees International Union.

1940s: Women Fill Wartime jobs

During World War II, African American women contributed significantly to the war effort by taking on industrial factory jobs and working in shipyards and other war production facilities. Referred to as “Black Rosie’s.” They worked as welders, machinists, assemblers and more. They also served in the military as nurses, in the Women’s Army Corps, and in the all-Black 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, responsible for clearing the backlog of overseas mail.

1941: Fair Employment Practices Committee

Under pressure from labor leader A. Philip Randolph, who planned a march of 250,000 Black workers in Washington, D.C., to demand jobs, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee. The order banned racial discrimination in any defense industry receiving federal contracts and led to more employment opportunities for African Americans.

1944: Admission to the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen Union. African Americans who maintained railroad locomotive engines had to sue the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen all the way to the Supreme Court to gain admission to the union in 1944.

1945: Maida Springer Kemp (1910-2005)

Kemp worked as a labor organizer in the garment industry and became the first Black woman to represent the U.S. labor movement overseas when she visited post-war Britain on a 1945 labor exchange trip. She went on to spend many years liaising between American and African labor leaders as a member of the AFL-CIO and became affectionately known as “Mama Maida” for her work. Throughout her life, she advocated for civil rights and women’s rights in America and internationally.

1946: Operation Dixie

Encouraged by massive growth in union membership (including African Americans) during the 1930s and 1940s, the Operation Dixie campaign launched an effort to organize the largely non-union Southern region’s textile industry and strengthen the power of unions across the United States. Spearheaded by the Congress of Industrial Organizations, in concert with civil rights organizations, the campaign covered 12 states. Operation Dixie failed because of racial barriers, employer opposition and anti-Communist sentiment that labeled anyone who spoke out as an agitator. In 1947, the Taft-Hartley Act was enacted, allowing states to adopt so-called “Right to Work” laws that limited union power.

1948: Zelda Wynn Valdes (1905-2001)

Fashion and costume designer Zelda Wynn Valdes was the first Black designer to open her own shop and business on Broadway in New York City. Her designs were worn by entertainers including Dorothy Dandridge, Josephine Baker, Marian Anderson, Ella Fitzgerald, Mae West, Ruby Dee, Eartha Kitt, and Sarah Vaughan.

1950s-2000s

1950s: Post-War Era

Despite some gains during World War II, African Americans still experienced high unemployment rates compared to white workers and faced significant barriers to upward mobility in the workforce. Labor was largely confined to low-wage, segregated jobs, primarily in service industries like domestic work, with limited access to skilled trades and significant discrimination within unions. These struggles fueled the developing Civil Rights movement and pushed for greater labor equality.

1953: Clara Day (c.1923-2015)

As a clerk at Montgomery Ward, she resented the segregation of white and Black employees, which led her to push for change. Clara Day first began organizing co-workers at Montgomery Ward in 1953 and went on to hold several roles in the Teamsters Local 743. She also helped found the Coalition of Labor Union Women and the Teamsters National Black Caucus. A passionate advocate for labor, civil rights and women’s rights, she helped bring attention to issues like pay equity and sexual harassment.

1954: Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926-2012)

In 1954, Norma Merrick Sklarek became the first Black woman to become a licensed architect in New York. Her projects included the United States Embassy in Tokyo, Japan in 1976 and the Terminal One station at the Los Angeles International Airport in 1984.

1950s-1970s: The Era of Social Movements. The three decades after World War Il saw the emergence of many movements in American society for equal rights, most notably the Civil Rights Movement. One milestone for this movement was passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, a landmark civil rights and labor law in the U.S., outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

1950s-1970s: Social Movements

During the Civil Rights Movement, African American artists like Nina Simone, and Harry Belafonte used their music and performances to advocate for social change. One significant event happened when Eartha Kitt was invited to Lady Bird Johnson’s “Women Doers Luncheon” in 1968. During the event, Kitt publicly spoke out against the Vietnam War and criticized several of President Johnson’s policies, consequentially derailing her U.S. career for more than a decade.

1963: Bayard Rustin (1912-1987) and Anna Arnold Hedgeman (1899-1990) Plan the March on Washington

While the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. made headlines with his “I Have a Dream” speech, it was Rustin who worked closely with the labor movement behind the scenes, planning and organizing the massive March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, one of the largest nonviolent protests ever held in the United States. As an openly gay man, Rustin’s crucial role in the March on Washington was often diminished and forgotten. As a member of the executive council of the AFL-CIO and a founder of the AFL-CIO’s A. Philip Randolph Institute, Rustin fought against racism and discrimination in the labor movement. Hedgeman was a civil rights activist, educator and writer who helped organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. She was a lifelong advocate for equal opportunity and employment.

1968: Poor People’s Campaign

This multiracial campaign, launched by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference under the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Rev. Dr. Ralph Abernathy, recognized that civil rights alone did not lift up African Americans. The campaign called for guaranteed, universal basic income, full employment and affordable housing. Dr. King said, “But if a man doesn’t have a job or an income, he has neither life nor liberty, nor the possibility for the pursuit of happiness. He merely exists.”

1968: Memphis Sanitation Strike

African American sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, represented by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), went on strike to obtain better wages and safety on the job, winning major contract gains. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the strike’s most influential supporter, was assassinated on April 4 as he was leaving his hotel room to address striking workers. Today, AFSCME produces the I AM STORY podcast, which follows the history of the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike as told by those who experienced it firsthand.

1969: League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW)

Established in Detroit, Michigan, the LRBW united several revolutionary union movements across the auto industry and other sectors. A significant influential Black Power group, the LRBW had a tremendous influence on the left wing of the labor movement. Their activism played a pivotal role at the intersection of race and class in the ‘post-civil rights’ era.

1970: Melnea Cass (1896-1978)

Known as the ‘First Lady of Roxbury,’ community organizer and activist Melnea Cass helped provide social services, professional training and labor rights education that empowered Boston’s most vulnerable workers. One of many examples is a program she co-created that provided childcare for working mothers. Her advocacy helped achieve a major legislative victory in 1970 when Massachusetts passed the nation’s first state-level minimum wage protections for domestic workers since the Great Depression.

1970s: Workforce and Unemployment

By 1970, about nine million African American men and women were part of the workforce in the United States. This workforce included the steel, metal fabricating, meatpacking, retail, railroading, medical services and communications industries, numbering one third to one half of basic blue-collar workers. Yet, at that time, the African American unemployment rate was still two to three times more than that of whites.

1970: Dorothy Bolden (1923-2005)

Future president Jimmy Carter presents a Maids Day Proclamation to Dorothy Bolden. Dorothy Bolden began helping her mother with domestic work at age 9. She was proud of her work, but also knew how hard it could be and wanted domestic workers to be respected as part of the labor force. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., her next-door neighbor, encouraged her to take action. In 1968, she founded the National Domestic Workers Union, helping organize workers on a scale never seen before in the United States. The union taught workers how to bargain for higher wages, vacation time and more. She also required that all members register to vote, helping to give workers a stronger voice both on the job and in Georgia policy.

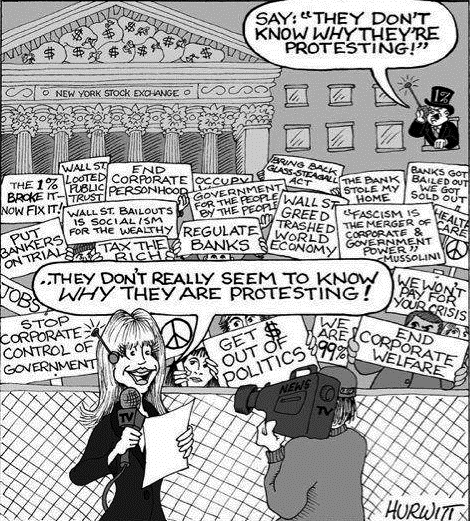

1979: Wage Decline Begins

Hourly wages for many American workers stagnated or dropped beginning in 1979, except for a period of strong across-the-board wage growth in the late 1990s. Researchers have found a correlation between the decline of unions and lower wages, and between lower wages and a growth in economic and social inequality, resulting in African Americans and Latino workers facing greater wage stagnation than white workers.

1980s: Declines and Milestones

During the 1980s, African American labor continued to face significant challenges including high unemployment rates, disproportionate job displacement due to industrial decline, and the widening wage gap compared to white workers. Particularly impacted were African American women, and blue-collar African American workers who relied heavily on shrinking union jobs during this period. Despite this, some progress was made with an increased Black union membership among men, affecting barriers to full equality in the workforce due to earlier civil rights movements.

1990: Hattie Canty (1933-2012)

Hattie Canty lived in Nevada and worked several jobs as a maid, a school janitor, and eventually a room attendant on the Las Vegas Strip. She became active in her union, was elected to the executive board of the Culinary Workers Union (CWU) in 1984 and became union president in 1990. She was the first Black woman and the first room attendant elected to this position in CWU. During her tenure, she brought together workers from several nations, helped push forward racial justice within the industry and her union, and founded the Culinary Training Academy, which helps people of color obtain better jobs in the hospitality industry.

1990: Americans with Disabilities Act

Inspired by the Civil Rights Act, and signed into law by President George H.W. Bush, Congress passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, prohibiting discrimination against all people living with developmental and physical disabilities in the workplace, transportation, public accommodations, state and local government services and telecommunications.

Recent History

2008: Smithfield Packing Plant Workers

Smithfield workers join the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW). After 16 years of organizing by African American, Latino, and Native American workers, the Smithfield Packing Plant in Tar Heel, North Carolina finally succeeded in joining the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union. Despite years of intimidation, violence, and illegal firings by the company’s management, the new local union was chartered as UFCW Local 1208. Today, there is a mural of civil rights leaders on the wall of the union hall.

2008: Barack Obama (1961- )

Barack Obama was elected to the first of his two terms as the 44th President of the United States becoming the first African American president in U.S. history. During his first two years in office, he signed many landmark bills into law, including his very first piece of legislation, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which impacted the labor movement. Obama also reduced the unemployment rate to the lowest it had been in more than eleven years.

2012: #BlackLivesMatter

Formed after the 2012 murder of a young African American man in Florida, Trayvon Martin, the Black Lives Matter movement grew as protests mounted against other killings, including the 2020 slaying of George Floyd in Minneapolis. In several communities, labor unions have built ties with #BLM chapters to address chronic issues of dehumanization, inequality, and exploitation.