Two Sides of the Same Coin: An Observance of the Strategies Utilized in the Women’s Suffrage Movement in 20th Century America

Cathleen Kane

On a brisk January morning in 1917, a group of one dozen women shifted on aching feet as they stood on hot bricks wrapped in newspapers in order to keep themselves warm. The women were united in front of one of the most important buildings in not only the United States, but the world. With chattering teeth, they held firmly onto their banners that were whipping in the wind and directed them toward the man who held their rights in his hands. Further downtown in the nation’s capital, groups of women worked in cozy offices planning how they would engage with the man in the White House. They worked together to write to members of some of the highest offices of the United States, the United States Congress, as well as devised letters to hand out to civilians advocating for their cause. These women, though separated by mere blocks, displayed just a few of the many strategies utilized by suffragists throughout the United States during the 20th century. These women worked toward justice and equal rights. These women worked toward winning their right to vote.

With the right to vote as the goal, what were the kinds of strategies utilized by suffragists in 20th century America, and why did these strategies make the difference? Two suffragist organizations, the National American Woman’s Association and the National Woman’s Party, used various strategies to gain the federal Nineteenth Amendment, granting the vote to women in the United States.[1] Through the will to push the limits of American society and government, greater access to resources including wealthy individuals supporting the cause, and stronger leadership from both suffrage groups, the 20th century was undeniably the time for women to gain the right to vote in America.

Historiography

The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, passed over one hundred years ago in the year 1920, denies states the ability to prohibit citizens from voting based on the account of sex.[2] However, when discovering how the amendment came to be, historians have primarily observed the beginnings of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States. Historians have discussed major figures including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and analyzed how it ended – women gaining the right to vote. While limited research has been written about the strategies used and the reasons why the 20th century was the time women were bound to gain suffrage in the United States, several works address various strategies used by 20th century suffragists and display why the 20th century was the century for women.

Beginning with Carmen Heider, the article ““Farm Women, Solidarity, and the Suffrage Messenger’: Nebraska Suffrage Activism on the Plains, 1915-1917” depicted a strategy, newspapers, used to keep women up to date and involved in the suffrage movement despite being thousands of miles from Washington D.C. Heider described that the strategy of utilizing suffrage newspapers, specifically The Suffrage Messenger, a Nebraska newspaper under the guidance of NAWSA, appealed to overlooked and underrepresented women of the suffrage movement in the 20th century, which included farm women.[3] Similarly to Heider, author James J. Kenneally discussed in his work women who are often overlooked and forgotten by historians, women who were arrested for the sake of suffrage. In his article “‘I Want to Go to Jail’: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919”, Kenneally discussed one of the strategies utilized by the NWP, women willingly being arrested and jailed to demonstrate their commitment to the suffrage cause. Kenneally also discussed how NAWSA displayed their commitment to President Woodrow Wilson through their support on the home front during World War I.[4]

In Joan Marie Johnson’s article, “Following the Money: Wealthy Women, Feminism, and the American Suffrage Movement”, the author made a bold argument regarding suffrage in America and the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment. Johnson argued that “women’s suffrage passed when it did because of the significant influx of these enormous donations [given by wealthy donors who supported the cause], as well as the leadership and shaped the strategies, priorities and success of the [suffrage] movement”[5]. In her article, Johnson also argued against the common conception held by historians that the wealthy women were controlling due to being the ones with the funds to give to the national organizations.[6]

In Jean H. Baker’s work, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, the author depicted the stories of some of the impactful suffragists in American history including Alice Paul with the intention of “recover[ing] the lost lives of these sisters of suffrage and through that development to understand why the suffrage movement developed when it did”.[7] Focusing on Baker’s fifth chapter, “Endgame: Alice Paul and Woodrow Wilson”, the author described Paul’s life, the strategies she administered during her time in NAWSA and the founder of the NWP, that included parades and picketing[8].

In the next two works, A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot authored by Mary Walton, and Alice Paul: Claiming Power written by J.D. Zahniser and Amelia R. Fry, the three authors depicted a biography of one of the most influential and yet forgotten American figures of the 20th century, Alice Paul. Walton argued the importance of Paul’s theory and practice of political protest. Paul modeled peaceful protest behaviors that influenced others to act in a similar manner throughout the 20th century. Walton described that Paul established legal precedents that protected future generations during civil protests.[9] Through Zahniser and Fry’s work, Zahniser intended to finish Fry’s mission to remember Alice Paul who “helped propel the suffrage cause to victory”.[10]

The final work utilized was Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, authored by Ellen Carol DuBois. In her work, DuBois depicted the women’s suffrage movement during the 20th century, focusing on various individuals including Carrie Chapman Catt. In her work, DuBois argued that suffragism was not a “single issue movement”. DuBois stated that women of various backgrounds and races fought not only for the right to vote, but also for birth control and peace during the 20th century. [11]

When the women’s suffrage movement in America is discussed by historians, they tend to focus on the beginnings of the suffrage movement, with events such as the Seneca Falls Convention, or the end of the movement, in which women gained the right to vote. Historians also focus on major figures throughout the movement such as Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Burns. However, this paper takes a deeper look at the women’s suffrage movement and focuses primarily on the strategies utilized during the 20th century that aided women in gaining the right to vote. In addition, this paper recognizes the impact made by the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association and the National Woman’s Party to the suffrage movement and the strategies utilized by the two parties rather than focusing on individual women involved in the movement.

Strategies implemented and utilized in the women’s suffrage movement during the 20th century were the first of their kind to be used by women. Strategies that were utilized included the use of open-air speeches, suffragist newspapers, lobbying, parades, and picketing, all of which will be the main strategies focused on in this paper. The strategies implemented and utilized by the women of NAWSA and the NWP, in which the organizations consisted of mostly white, middle-class women, displayed that American women were not handed the right to vote, rather with these strategies, they fought for the right to vote. Were it not for the brave women sacrificing their time, money, and for some, their freedom, countless women throughout the country would not have the fundamental right given to them as American citizens.

Suffrage in the 20th century

Before parades of suffragists donned in purple, white, and gold, marched down Pennsylvania Avenue or before open air speeches were shouted to the public, there was the suffrage movement at the beginning of the 20th century. 1900, a new century for women to make their voices heard had appeared, but the suffrage movement in America had come to a standstill. While there had been some progress in women’s education and work outside of the home, there were not “many changes in the legal status of women”[12] according to Jean H. Baker. Women were still not allowed to sit on juries during a legal trial, with wages that married working women earned still being controlled by their husbands, and divorce laws favoring men, women needed the vote to change their legal status.[13] Gaining the vote was also at a standstill when the new century began in the United States as some of the largest organizations for suffrage, including NAWSA, “had run out of ideas”.[14] While NAWSA did present new committees that would draw groups of women into the suffrage movement, such as the working class with the implementation of the Committee on Industrial Work, the strategies used by NAWSA remained in the 19th century.[15]NAWSA strategies already established included holding annual conventions, such as the 1906 convention in Baltimore, and testifying before Congress with promises that “women throughout the country will come from generation to generation, just so long as necessary” however, these strategies were aged, overused, and in desperate need for a change.[16]

A new century did not mean new support for the suffragists either as “many legislators yawned, cleaned their nails, turned their backs, and otherwise displayed their silent contempt for the women” during NAWSA’s yearly lobbying.[17] The start of the 20th century also did not place a national amendment for women’s enfranchisement any higher on legislators list of top priorities because, according to Baker, before the debate of a national amendment, “three other amendments – the income tax, direct election of senators, and prohibition – had taken precedence”.[18] Finally, if matters could not be any more dire for a call to action at the start of the 20th century, the founders of the suffrage movement in America were meeting their demise as Lucy Stone died in 1893 with Elizabeth Cady Stanton to follow in 1902.[19] Death came for all of the great leaders as even Susan B. Anthony who promised to continue the fight for suffrage “‘as long as [she was] well enough to do the work’”[20] passed away on March 13, 1906.[21] The 20th century needed new leaders and strategies quickly. Enter two of the most prominent figures of the suffrage movement, Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul, two individuals who would go on to lead two suffrage organizations that embraced various strategies, which included the use of newspapers and picketing, to gain the vote for women in the 20th century.

Emerging leaders and held beliefs

Being one of the most powerful suffrage organizations in the United States going into the 20th century, the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association carried forth their traditional strategies established by previous suffragists, including Anthony and Stanton. Carrie Chapman Catt was at the helm of the organization as NAWSA’s President at the beginning of the century, 1900 to 1904, and again at the end of the battle for the ballot, resuming her position as President from 1915 to 1920.[22] From NAWSA’s founding and throughout Catt’s first term as president, the organization focused on a state-to-state approach.[23] A state-to-state approach involved NAWSA suffragists traveling the country to advocate for the legalization of women’s enfranchisement in a particular state, such as Colorado, rather than focusing on a federal amendment guaranteeing women across the country the right to vote. NAWSA would continue this state-to-state approach until 1915 when the reinstated President Catt saw how difficult of a task she faced, especially with a state-to-state approach. Catt realized that she would be in charge of “reorganizing the thousands of members of NAWSA into an orderly suffrage army” and “keep state chapters from flying off on their own”, therefore she needed to have a changed viewpoint in how women were to gain suffrage.[24] Catt also witnessed the failure of a state-to-state approach after attempting to convince the voting men of New York state to enfranchise women in the state.[25] After countless hours and resources, including advocating suffragists going door to door, New York women were still not able to vote as “only six of the state’s sixty-one counties voted in favor [of women’s enfranchisement]”.[26] If that were not enough, Catt understood that World War I was raging in Europe with hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children being killed or injured. Catt used these unspeakable strategies to further the cause of a national amendment as she described that with full political rights, including voting, “[women] would find a way to settle disputes without killing fathers, husbands and sons”.[27]

Catt’s changing viewpoints of a national amendment and the tactics that would follow to gain the amendment would become known as her “Winning Plan”. According to author Joan Marie Johnson, Catt’s “Winning Plan” was to gain the national amendment through campaigning in certain states, such as New York and Oklahoma, as well as lobbying Congress.[28] Campaigning in certain states and lobbying would give momentum to pass the national amendment while also gaining women in the campaigned states suffrage.[29] Catt made her “Winning Plan” and viewpoints known throughout her term as President as on December 15, 1915, to a crowd of five hundred suffragists, she explained that “all of NAWSA’s resources would be concentrated on winning a federal constitutional amendment”.[30]

Besides their belief in the state-to-state approach, and the eventual approach of gaining a national amendment, NAWSA strongly endorsed its members to support the Democratic President standing in their way of the vote, Woodrow Wilson. The women supported the President in multiple ways throughout his time in the Oval Office and during the First World War. From providing First Lady Edith Wilson with flowers during the President’s visit to Boston in 1917 to endorsing women to participate in war efforts during the First World War which included “end[ing] its suffrage efforts and encourag[ing] its members to replace suffrage work activism with war work”, NAWSA supported the President.[31] As a result of their efforts, President Wilson had “‘great and sincere admiration of the action taken’” by the women of NAWSA, therefore, to the organizations satisfaction, gaining some support to their efforts to win the amendment.[32]

With a new century calling for new strategies, one young woman from Moorestown, New Jersey by the name of Alice Paul was ready to answer the call and experiment with new strategies to gain women the right to vote in the United States.[33] After finding her commitment to suffrage when overseas in England, Paul came back to the United States and joined the NAWSA in 1910[34]. Paul worked with NAWSA for two years as the leader of the Congressional Congress, “a committee of NAWSA responsible for lobbying Congress”.[35] However, Paul’s commitment to NAWSA began to take a turn when in “mid-April” 1913, “Alice stunned the leadership [of NAWSA] with the news that she had formed a membership organization, the ‘Congressional Union’”[36]. The Congressional Union, according to author Mary Walton, would “push for a federal amendment”, something that NAWSA did not currently align with in 1913 as they were focused on the state-to-state strategy until 1915.[37] The Congressional Union that Paul formed was the predecessor of one of the most radical suffragist organizations to have swept the country. With radical tactics that included women picketing in front of the White House and voluntarily being arrested for the cause of suffrage, the Congressional Union would go on to be called the National Woman’s Party, and its leader would become no other than Alice Paul.

Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party also held certain unpopular and unpatriotic beliefs as well as their belief in the national amendment. Unlike the women of NAWSA who supported President Wilson and the Democratic Party, Paul did not support the President, rather she held great anger against him. According to Baker, Paul “meant to hold Wilson and his Democratic Party responsible for the failure to get a suffrage amendment passed by Congress”.[38] Paul would hold the President responsible throughout the suffrage movement and the women of the NWP would show their discontent to the President through committing “unpatriotic” acts. These “unpatriotic” acts, included interrupting his speech on July 4, 1916 as Mabel Vernon, executive secretary of the NWP, questioned the President on if he cared about the interest of all people, why did he oppose the national amendment.[39] This kind of action was met with high criticism including being bashed in newspapers.[40] Paul remained frustrated that throughout the United States’ involvement in World War I, the President relied on the women back home to aid in the war efforts, something NAWSA did not mind doing, but in return they received nothing. Paul also questioned throughout the war that if Wilson was fighting for the world to be “made safe for democracy”, then why is there still a lack of democracy on the home front considering that women were not allowed to partake in America’s democracy.[41] Alice Paul had the goal of convincing President Woodrow Wilson that the vote for women needed to be guaranteed across the country, and through the various strategies used by both Paul’s National Woman’s Party and Catt’s National American Woman’s Suffrage Association, the 20th century would be the century for women.

The strategies used by the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association speeches

One of the most powerful tools that a person has is their voice. The human voice can do extraordinary tasks including convince people to join a cause. One of the various strategies that NAWSA used to gain the federal amendment in the 20th century was the use of speeches. According to historian and editor Susan Ware in the work, American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776 – 1965, NAWSA, after decades of lobbying and gathering petitions, decided to take a new approach to making their suffrage message heard and create new interest in their cause, the use of open-air meetings.[42]. An open-air meeting required participating women to stand outside of buildings and project their message of suffrage to “the average human being, busy and tired”.[43] The practice of utilizing open-air speeches was best described by student turned suffragist, Florence H. Luscomb, who recounted in her work, “Our Open-Air Campaign”, the process of openly speaking and campaigning to the general public on the topic of women’s enfranchisement.[44]Luscomb described that as a member of the VOTES FOR WOMEN COMMITTEE in Boston, she and her fellow suffragists spoke to diverse crowds who might have not been well-informed of the suffrage movement with listeners including children and police officers.[45] The speakers would travel from town to town across a state to stand outside on the “busiest corner of the town square” with a “borrow[ed] Moxie box” to stand on, and begin to speak on the topic of suffrage to anyone who would listen.[46] These open-air speeches were modeled after the English suffragettes who had much success with the strategy, and the goal was to “make it [the message of suffrage] picturesque” and to “make it easy” as the general public may already had preconceived thoughts on suffrage or little knowledge on the matter.[47]

The demonstration of open-air speeches was one of the various strategies utilized that reinforced that the 20th century was undeniably the time for women to gain the right to vote because it aided women in gaining a new audience of potential supporters. In the 19th century, NAWSA mainly focused on projecting their message and gaining the support of politicians, such as Congressmen, through lobbying. However, with the new 20th century strategy of open-air speeches, women were advocating their enfranchisement “not to a small body of lawmakers, but to a large body of the people, those who elect the lawmakers”.[48] Women were no longer standing in the heart of the Capitol Building having their cries for fulfillment of democracy fall onto the deaf ears of bored Congressmen, rather, they were out in the streets of major cities to express their message to those who might not be aware of the cause. By addressing the public, suffragists were given the chance to inspire others to not only join the movement, even if it just meant supporting the idea of women voting, but to also advocate for the public to use their vote and voice to elect those who do support the women’s cause during the next election.

Newspapers and other readings

Another strategy utilized by NAWSA to gain the federal amendment in the 20th century was through the creation and distribution of newspapers as well as other materials. Throughout the 20th century NAWSA distributed newspapers nationwide, including the Woman Citizen, and regional newspapers, an example being The Suffrage Messenger, which was published in Nebraska.[49] Newspapers did not just simply update women around the country or regionally with the latest suffrage news, these newspapers brought women together. According to historian Carmen Heider, suffrage newspapers served a much larger purpose than to be picked up, read, and then tossed aside; rather, through the columns of suffrage newspapers, women who were overlooked in the suffrage movement were represented, an example being the rural farmers of Nebraska. According to Heider, The Suffrage Messenger of Nebraska, “served as the primary means through which Nebraska activists reached out to their audiences”, inviting the women of the grandest cities to the rural plains to write to the newspapers about their suffrage experience and any questions that they may have about the movement.[50] By reaching out through newspapers in the 20th century, activists were also reaching out to women who may not have been considered to be potential members of the suffrage movement in the previous century, women in rural communities.[51] Newspapers provided more information to these women who were somewhat isolated from the movement, due to their large distances from cities including New York City or Washington D.C., and with suffrage newspapers, farmer’s wives could be involved in the movement. With more knowledge to a community comes more support, and with more support comes the chance to make a difference sooner.

Newspapers not only brought women together, but they also encouraged women to join the fight, including rural women of the plains, through advocating the raising of funds for the cause. The Suffrage Messenger promoted an interesting fundraising event that involved women from all around Nebraska, including women of rural areas as they could understand and appreciate the so-called “suffrage pig movement”.[52] According to Heider, the fundraiser began in Louisiana and continued across the West due to farm women wanting to contribute to the suffrage cause, but having no money, so instead, they offered what they did have, pigs.[53] The Suffrage Messenger ran with the idea and the women of the plains had the opportunity to present their pigs and have the animals featured on the weekly “Suffrage Pig Honor Roll ”, to promote others to donate pigs rather than money.[54] The pigs presented by the farm women would eventually be sold to the highest bidder with the funds going toward the suffrage cause.[55] Through bringing women together from all points of the country to write to newspapers and to entice the raising of funds for the suffrage movement in unique ways, the strategy of using newspapers allowed underrepresented women of the suffrage movement to be active participants in the fight toward women’s enfranchisement during the 20th century.

The Woman Citizen and The Suffrage Messenger were thriving examples of how NAWSA brought citizens of the United States not only news on suffrage, but also various opportunities to participate in the battle to get women to the polls in the 20th century, such as through fundraising events. However, newspapers were not the only pieces of literature being distributed by NAWSA in the 20th century as they also distributed other variations of works to be read and understood. According to historian and author Joan Marie Johnson, “They [suffragists] published everything from tracts to weekly newspapers to full-scale books focused on documenting the movement, organizing workers, and converting the public to the cause”.[56] One of the prime examples of these various kinds of works published by NAWSA was the book, Your Vote and How to Use It, authored by NAWSA member Gertrude Foster Brown.[57] After the women of New York state received the right to vote in 1917, NAWSA and Brown decided that it was time to publish a work in regards to how to vote. The work would be geared toward the “average” woman, whether she was working or tending to her home as a wife or mother, because it was essential for women to understand how to utilize their vote.[58]Throughout the work, Brown described major points of information for new voters to learn about including what government was and the business of government, which were topics that women may have had little to no experience with or knowledge about before receiving the right to vote.[59]

Through the use of other literary materials, including books, NAWSA enlightened women on how to utilize their vote and the importance of voting as the 20th century progressed. NAWSA was emphasizing to New York women that they had the opportunity that very few other women had, therefore, they needed to utilize it in order to display to other voters, especially male, that the decision to give women the vote was the correct one. With more women rushing to the polls on election day, due in part thanks to literature published by NAWSA, women displayed that they were not only enthusiastic about the vote, but women had the ability to vote for representatives that fought for national suffrage.

Lobbying

As the 19th century progressed into the next, NAWSA, while the organization implemented new strategies to gain the federal amendment, remained true to one of their original strategies, lobbying. The act of lobbying consisted of groups of women seeking support from a politician on the issue of women’s suffrage as this would possibly lead to the politician gaining favor for the issue at the highest level, such as in Congress. During the 19th century, NAWSA’s lobbying efforts relied on the “uncompensated devotion of its adherents”, however, as the United States entered the 20th century, women had the desire to become paid for their efforts, therefore if they were to keep up with lobbying, NAWSA needed to find funds, and fast.[60] In May 1917, the women’s desires for payment would come true as NAWSA received its first check from a wealthy donor named Mrs. Frank Leslie who left over one million dollars to NAWSA’s suffrage fund to be used any way President Carrie Chapman Catt saw fit.[61] With the outrageous funds, Catt not only paid some of the women for their time, but with more money now available, she saw that a new century meant a new way to lobby.

Lobbying transformed in the 20th century and helped lead the way for the federal amendment to pass as the practice no longer became a disorganized group of volunteers annoying Congressmen, rather, it became a well-oiled machine. With Maud Wood Park leading NAWSA’s congressional lobbying efforts in March of 1917, the organization soon had twenty-five regular lobbyists, almost all of whom were volunteers.[62] The twenty-five women lived and worked in Washington D.C. in order to get into contact with 435 members of Congress and 96 senators sitting in Washington D.C. at one time in the year 1917.[63] The lobbyists also worked with state congressional chairmen who represented NAWSA’s state branches to, according to historian and editor Susan Ware, put the idea of suffrage into the minds of those in the highest positions of power in the country.[64] Director Maud Wood Park also received guidance on the new, 20th century tactic of “Front Door Lobbying” from Helen Hamilton Gardener, a NAWSA member who had close relationships with powerful Democratic politicians including Speaker of the House Champ Clark and even Woodrow Wilson himself.[65] Under the leadership of Wood and the guidance of Gardener, the NAWSA lobbyists of the 20th century learned the “delicacies of effective lobbying” which they did not implement in the previous century.[66] These “delicacies” consisted of methods that were lady-like which included “don’t nag, boast, [or] lose your temper”, but methods that also showed the Congressmen that they were determined with methods that included “overstay[ing] your welcome and allow[ing] yourself to be overheard”.[67] Working together as one unit, the lobbying women and the state congressional chairmen needed to “compel this army of lawmakers to see woman suffrage, to talk woman suffrage every minute of every day until they heed our plea” as this was to be the woman’s hour and century.[68]

The strategies used by The National Woman’s Party Parades

Before being expelled from NAWSA and establishing the Congressional Union in 1914, which would become the National Woman’s Party, suffrage leader Alice Paul took part in developing one of the grandest strategies established during the 20th century to gain the federal amendment, parades. Parades were a new concept to women’s suffrage fight and it was a unique way to not only engage women to participate in the ongoing fight, but to also present to the American public the message of the suffragists. With the occurrence of a parade, the possibilities in broadcasting a message to a national audience were great with one of the most famous examples of a parade occurring the day before President Wilson’s inauguration. Wanting to make themselves and their message of suffrage memorable, Alice Paul and the women of NAWSA had the idea of marching down the traditional parade route that the newly inaugurated President would travel on, including Pennsylvania Avenue.[69] Paul understood the importance of the parade route being down Pennsylvania Avenue as it would send the message that “women stood at the gateway of American politics, willing and able to stand alongside men as full-fledged citizens”, therefore adding to the visual reasoning of the parade.[70]

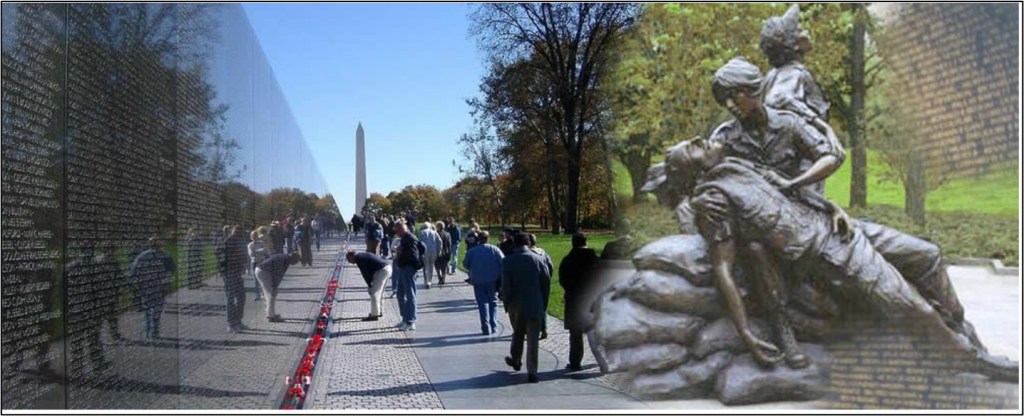

On March 2, 1913, the day before President Woodrow Wilson was to be inaugurated, more than eight thousand women marched down the streets of Washington D.C. led by Alice Paul with a crowd of 250,000 onlookers gazing at the spectacle before them.[71] The parade offered participants from all around the country and from all walks of life including “social workers, teachers, business women, and librarians”, to join the walk for suffrage.[72] With this 20th century strategy, women were brought together to speak as one voice to demand “an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of the country”.[73] Through the display of the parade, the women were also entertaining the public through interesting visual displays, but they were displaying to the American public and government that most women stood united on the issue of suffrage. They showed the crowds that women’s suffrage is no longer just a few hundred women gathering to speak, rather it was thousands of women seeking their enfranchisement.

While the 20th century strategy of parades drew in mass crowds of suffragettes to participate, so too did it draw in large crowds of spectators, including those who were not too happy to see the women marching for suffrage. Shortly after the parade began, “spectators challenged suffragists’ right to the street” as crowds full of rowdy and drunk men began to surround the women on all sides, blocking them from continuing forward on their route.[74] After storming the streets, the men proceeded to act in rude and dangerous ways as described in the March 3, 1913 issue of the Woman’s Journal and Suffrage News. The front page of the newspaper, published a day after the event occurred, described how “women were spit upon, slapped in the face, tripped up, pelled with burning cigar stubs and insulted by jeers and obscene language too vile to print or repeat”.[75] Though these actions were disturbing and awful to the women, Alice Paul and the other leaders of NAWSA “recognized that a publicity coup awaited them” as a result of these violent acts.[76] After these vicious attacks, newspapers, including The Woman’s Journal and Suffrage News, published the accounts of several women including Anna Howard Shaw who not only described the bite that she received but how she was never “so ashamed of our national capital before”.[77] Through describing their accounts and feelings of what happened during the parade, suffragists drew attention, and more so, sympathy from the American public and government officials in regards to what occurred. With this newfound attention and sympathy, the suffrage movement was not only discussed, but it showed to the American public and government that the women were brave to fight off these men, therefore, they deserved the vote.

Picketing

On January 9, 1917, the women of the Congressional Union, soon to become the National Woman’s Party, gathered in their Washington D.C. headquarters to scheme.After delivering yet another speech to President Wilson that same afternoon about women’s enfranchisement, suffragist Maud Younger expressed her concerns to the group. They already “‘had speeches, meetings, parades, campaigns, organizations’’ to show American society and government that they desired the vote, but she questioned what new method could be utilized by the women to draw attention to their cause.[78] The new method was created by Alice Paul and Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of one of the founders of the suffrage movement in the United States, Elizabeth Cady Stanton.[79] The 20th century strategy would not only impact the women’s movement moving forward, but the way that Americans protest.[80] The strategy involved picketing in front of the most important building in America, the White House. The strategy utilized in the 20th century, made headlines as it was the first documented time in American history that a group, male or female, picketed in front of the White House, therefore forcing the attention of President Wilson and making him consider the idea of women suffrage.[81]

The protest-altering practice of picketing began in the early morning of January 12, 1917, as NWP members braced for the cold with their winter coats, while “their torsos were bisected by purple, white and gold sashes”, the colors of the National Woman’s Party.[82] Unlike in the past century, the suffragists were not clamoring to meet with the President and speak on the subject of suffrage through speeches or lobbying, rather, the ladies of the 20th century were silent as they allowed for their strongly worded picket signs and banners to do the talking, therefore putting pressure on the President to act. Day in and day out for nearly three months, January to March 1917, the silent sentinels of the National Woman’s Party would stand outside of the prestigious institution with signs that bore messages directly toward President Wilson with phrases including “MR. PRESIDENT, WHAT WILL YOU DO FOR WOMAN SUFFRAGE?”.[83] With the 20th century strategy of picketing, the women not only attempted to gain the attention of the President, but also the media. After they saw women standing outside of the White House with “unpatriotic” banners and signs, newspapers went on a feeding frenzy, including the New York Times, as they found their new story.

Published on “January 11”, The New York Times claimed that the members of the NWP created “organized harassment of the President” and the newspaper bashed the women by calling their act petty and a monstrosity.[84] The article continued as The Times tried to influence its readers that if women were given the vote, the government would be overrun with voters who believe that the act of picketing in front of the White House was “natural and proper” for them to do as well, therefore creating “political danger”.[85] The New York Times was not the only organization to disapprove of the suffragists actions, but so too did NAWSA’s president, Carrie Chapman Catt look on with disdain as she described the picketing as “‘a childish method of appeal” and one that “will never bring a result’”.[86] Although they were bashed in newspapers across the country and by Catt, the suffragists’ message was out, newspapers across the country were talking about women’s enfranchisement. With more discussions came more support, donations, and supplies to continue the campaign including “thermoses of coffee, and sometimes mittens or fur pieces” from individuals supportive of the cause.[87] The 20th century strategy of picketing not only drew support and attention to the suffrage cause, but it enhanced the pressure on Woodrow Wilson as he had two options, “he could remove the pickets. Or he could give them the ballot”[88]. Through the immense pressure put on Wilson and their determination to hold out for as long as possible, the 20th century would end in women gaining the right to vote.

Conclusion

After years of pushing the limits of American society and government, the women’s suffrage movement had a major victory with the Nineteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution, being ratified on August 18, 1920. Unfortunately, the fight for suffrage was not over for all women because despite their enormous efforts throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, various groups of women, including African American women, did not immediately receive the right to vote. Due to Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation and through states placing obstacles at the polls, including poll taxes and literacy tests, it became increasingly harder for women of color to vote.[89] African American women and women of color would continue the fight for women’s suffrage until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law on August 6, 1965. The act outlawed discriminatory voting practices, including the imposition of prerequisites including poll taxes or literacy tests, therefore allowing African American women and women of color to enact their right to vote as citizens of the United States without the worry of obstacles standing in their way.[90]

While the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association and the National Woman’s Party utilized different strategies to gain women the right to vote, these two organizations both held the belief and fought for women’s suffrage, making them two sides of the same coin. Throughout the 20th century, NAWSA and the NWP transgressed the boundaries put in place for women during the century, including the idea that women needed to allow male voters and politicians to decide if and when women’s enfranchisement would be enacted.

While there were great strides and victories made by the suffragists of the 19th century, 20th century suffragists understood that with changing times came changing strategies and adapted their methods to make their message of suffrage heard. Suffragists of the 20th century had a greater will to push American society and government, greater access to resources including wealthy individuals, and stronger leadership in the forms of Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul. With these ideals along with their strategies of developing suffragist newspapers, new tactics of lobbying, and publicity stunts including parades and picketing in front of the White House, the 20th century was undeniably the time for women to gain the vote in America.

A note for teachers

The work presented above is my senior capstone project in which I developed for the conclusion of my history major. As a secondary education and history major, therefore a future history teacher, I strive to make little known stories of history told, especially in my classroom. Not having had learned about the women’s suffrage movement until my first year of college, I have developed a passion for the history of the movement, not only because I am woman, therefore I owe great thanks to the women who fought for my right to vote, but also because I never learned about the subject in middle school or high school. It is vital that as history teachers, we teach all history, including the history that represents the students in our classroom. Although my work focuses primarily on NAWSA and the NWP, two organizations in which white women were primarily members, there are countless African American women and women of color that were featured in the suffrage movement. I encourage you to look into the suffrage movement and teach your students to research the movement before falling into the preconceived notions of the women’s suffrage movement including that white woman, especially middle-class women, were the only ones fighting for suffrage.

Another preconceived notion to consider and to teach your students the truth about is that women were “given” the right to vote. In my work above I describe the strategies used by women in the 20th century; these strategies were implemented by women for women as they had to fight for their rights, they were not just handed to them. I encourage you to look into other strategies utilized throughout the 19th and 20th centuries as there are countless more including women being arrested for the sake of suffrage and various women developing enthralling speeches. From these strategies, whether you research them or your students research them, countless examples of peaceful protests can be found, and these strategies developed during the women’s suffrage movement inspired other peaceful protest strategies utilized throughout major movements of the 20th century such as the Civil Rights Movement.

I understand that as teachers we must adhere to the curriculum presented to us, and that curriculum may sometimes leave out topics of historical significance, such as the women’s suffrage movement. However, you can incorporate the suffrage movement and women’s history overall, into your lessons based around the curriculum you were given as I have done it in my own lessons that I have taught so far in my field work. The first way that you can incorporate women’s history into your lessons is by incorporating women into your examples. When I was in my field observations this fall, the class I was observing, United States History I, was learning about the Gilded Age and its philanthropists. My cooperating teacher wanted to dive deeper into history and not just present the well-known names of Rockefeller and Carnegie, rather, she wanted to find new names that could serve as inspiration for our students. This led her to learn about Madam C.J. Walker, an African American philanthropist who became one of the wealthiest female entrepreneurs of the Gilded Age and of all time. This was so simple for her to do; she did some quick research on famous women of the time period, and it made a huge impact on those in the class, therefore I encourage you to take a few minutes and do the same.

Researching for examples of women of the time period is not the only great way to bring women’s history into your classroom as there is another way that I implemented during my field work this fall, creating a lesson around women’s history. While we just finished the Gilded Age and still had a few lessons before we would briefly touch on the women’s suffrage movement, my cooperating teacher encouraged me to develop my own lesson, and he was enthusiastic at the idea of me doing a lesson on women’s history. I decided to do my women’s history lesson not on the women’s suffrage movement, rather I wanted to give myself a challenge and I wanted to give a review to my students. Another way that you could implement women’s history into your lessons is through developing a lesson around women’s history in the time periods that you already covered. For example, in our class, we covered the colonies, the American Revolution, the Civil War, and the Oregon Trail, therefore, I found female historical figures involved during those time periods and developed my lesson around them. I developed my own and utilized others’ worksheets around Phillis Wheatley, women of the American Revolution, Sojourner Truth, women of the Civil War, and women of the Oregon Trail. For all of the subjects I utilized articles from various historical websites as well as primary sources. This lesson only took one class period, and my students, after completing the activities, expressed how much they enjoyed learning about the women of these time periods and some students even expressed that they have never even had the chance to learn about the women I included in the lesson. This lesson can be implemented during any time period in which you are teaching and it is a great, and easy, way to implement women’s history into your classroom.

Women’s history is an often forgotten subject. There are countless women that have made their mark in history, including Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt, but it is up to us, history teachers, to keep their stories alive. The women’s suffrage movement is also a topic that is not discussed in-depth in high school history classes, but this topic provides the opportunity to dive into various subjects including the peaceful protest strategies first developed during the movement, and the various women that worked together to fight for a tremendous accomplishment. I encourage you to take the chance, even if it’s just by implementing women into examples, or by creating a lesson revolving around women’s history to try to implement this little known history, along with many others in your classroom as all stories deserve to be told and these stories can impact and inspire countless students.

References

Primary Sources

Florence H. Luscomb. “Our Open-Air Campaign” in American Women’s Suffrage edited by Susan Ware. United States: Library of America, 2020: 307 – 314.

Gertrude Foster Brown. “From Your Vote and How to Use It” in American Women’s Suffrage edited by Susan Ware. United States: Library of America, 2020: 565 – 568.

Maud Wood Park. “To NAWSA Congressional Chairmen” in American Women’s Suffrage edited by Susan Ware. United States: Library of America, 2020: 520-524.

Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Front page of the “Woman’s journal and suffrage news” with the headline: “Parade struggles to victory despite disgraceful scenes” showing images of the women’s suffrage parade in Washington, March 3, 1913. Washington D.C., 1913. Photograph.

The Library of America. (2020). American Women’s Suffrage. Edited by Susan Ware. United States: Library of America.

The New York Times. “Silent, Silly, and Offensive” in American Women’s Suffrage edited by Susan Ware. United States: Library of America, 2020: 525 – 527.

Secondary Sources

Baker, Jean H. Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists. New York: Hill and Wang: (1st), 2005.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020.

Harris & Ewing. Cameron House or “Little White House.” Congressional Union Convention headquarters showing glimpse of Cosmos Club at left, Belasco theater at right and glimpse of U.S. Treasury building in background. United States Washington D.C, 1916. [Jan] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000438/.

Heider, Carmen. “Farm Women, Solidarity, and the Suffrage Messenger Nebraska Suffrage Activism on the Plains, 1915-1917”. Great Plains Quarterly (2012). *FARM WOMEN, SOLIDARITY, AND THE SUFFRAGE MESSENGER NEBRASKA SUFFRAGE ACTIVISM ON THE PLAINS, 1915-1917 (unl.edu)

Johnson, Joan Marie. “Following the Money: Wealthy Women, Feminism, and the American Suffrage Movement”. Journal of Women’s History 27, no. 4 (2015): 62-87. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/605149/pdf

Kenneally, James J. “’I Want to Go to Jail’: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919”. Historical Journal of Massachusetts, (Winter 2017): 103-133. https://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/I-Want-to-Go-to-Jail.pdf

National Archives, “Voting Rights Act 1965”, Milestone Documents, February 8, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act.

United States Congress, “The Constitution of the United States: The Nineteenth Amendment”, Constitution Annotated, U.S. Constitution – Nineteenth Amendment | Resources | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress

Walton, Mary. A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Zahniser, J.D. and Fry, Amelia R. (2014). Alice Paul: Claiming Power. The United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2014.

[1] The National American Woman’s Association and the National Woman’s Party will be abbreviated throughout the work as “NAWSA ” and the “NWP ”, respectively.

[2] United States Congress, “The Constitution of the United States: The Nineteenth Amendment”, Constitution Annotated, U.S. Constitution – Nineteenth Amendment | Resources | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress

[3] Carmen Heider, “Farm Women, Solidarity, and the Suffrage Messenger: Nebraska Suffrage Activism on the Plains, 1915 – 1917”, Great Plains Quarterly (2012): 115.

[4] James J. Kenneally, “‘I Want to Go to Jail’: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919”, Historical Journal of Massachusetts 45, no. 1 (2017): 103-127.

[5]Joan Marie Johnson, ““Following the Money: Wealthy Women, Feminism, and the American Suffrage Movement”, Journal of Women’s History 27, no. 4 (2015): 63.

[6] Ibid, 2,3.

[7] Jean H. Baker. Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists. (Hill and Wang: New York. (1st), 2005), 11.

[8] Ibid, 183-230.

[9] Mary Walton, A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, (Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2010), 252.

[10] J.D. Zahniser and Amelia R. Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, (Oxford University Press: The United States of America, 2014), 4.

[11] Ellen Carol DuBois, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, (Simon and Schuster: New York, 2020), 3-5.

[12] Baker, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, 188.

[13] Ibid, 189.

[14] Ibid, 189.

[15] DuBois, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, 161.

[16] Ibid, 161.

[17] Baker, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, 189.

[18] Ibid, 190.

[19] Ibid, 190.

[20] DuBois, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, 165.

[21] Ibid, 165.

[22] Johnson, “‘Following the Money’: Wealthy Women, Feminism, and the American Suffrage Movement”, 66.

[23] Johnson describes that from the 1880s to the early 1910s, NAWSA focused on a state to state approach to suffrage. (Ibid, 65).

[24] DuBois, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, 205-206.

[25] Ibid, 202.

[26] Ibid, 203.

[27] Ibid, 207.

[28] Johnson, “’Following the Money’: Wealthy Women, Feminism, and the American Suffrage Movement”.

[29] Ibid, 68.

[30] DuBois, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, 206.

[31] Kenneally, “‘I Want to Go to Jail’: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919”, 113. Heider, “Farm Women, Solidarity, and the Suffrage Messenger: Nebraska Suffrage Activism on the Plains, 1915-1917”, 115.

Baker, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, 215.

[32] DuBois, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, 223.

[33] Zahniser and Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, 5.

[34] Baker, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, 197.

[35] Ibid, 206.

[36]Walton, A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, 84.

[37]Ibid, 84.

[38] Baker, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, 206.

[39] Walton, A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, 135

[40] Ibid, 135.

[41] Ibid, 160.

[42] Susan Ware, American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776 – 1965, (Literary Classics of the United States, Inc.: New York, 2020), 307.

[43] Ibid, 307.

[44] Florence H. Luscomb, “Our Open-Air Campaign”, in American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776 – 1965, ed. by Susan Ware (Literary Classics of the United States, Inc.: New York, 2020), 307-314.

[45] Ibid, 308.

[46] Ibid, 310.

[47] Ibid, 307.

[48] Ibid, 307.

[49] Heider, “Farm Women, Solidarity, and the Suffrage Messenger: Nebraska Suffrage Activism on the Plains, 1915-1917”, 115.

[50] Ibid, 114, 116.

[51] Ibid, 114.

[52] Ibid, 119.

[53] Ibid, 119.

[54] Ibid, 119.

[55] Ibid, 119.

[56] Johnson, “‘Following the Money’: Wealthy Women, Feminism, and the American Suffrage Movement”, 69.

[57]Gertrude Foster Brown, “Your Vote and How to Use It”, in American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776 – 1965, ed. by Susan Ware (Literary Classics of the United States, Inc.: New York, 2020), 565.

[58] Ibid, 565.

[59] Ibid, 566-67.

[60] DuBois, “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote”, 219.

[61] Ibid, 219-220.

Johnson, “‘Following the Money: Wealthy Women, Feminism, and the American Suffrage Movement”, Journal of Women’s History 27, no. 4 (2015): 70

[62] DuBois, “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote”, 220.

Maud Wood Park,, “To NAWSA Congressional Chairmen”, in American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776 – 1965, ed. by Susane Ware, (Literary Classics of the United States, Inc.: New York, 2020), 520.

[63]Ware and The Library of America, American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776 – 1965, 520.

[64] Ibid, 520.

[65] DuBois, “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote”, 222.

[66] Ibid, 222.

[67] Ibid, 222.

[68] Carrie Chapman Catt. “The Crisis”, ed. by Susan Ware (Literary Classics of the United States, Inc.: New York, 2020), 495.

[69] Zahniser and Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, 135.

[70] Ibid, 136.

[71]Baker, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, 183-85.

[72] Walton, A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, 72-73.

[73] Ibid, 72.

[74] Zahniser and Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, 146.

[75] Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Front page of the “Woman’s journal and suffrage news” with the headline: “Parade struggles to victory despite disgraceful scenes” showing images of the women’s suffrage parade in Washington, March 3, 1913. Washington D.C., 1913. Photograph.

[76] Zahniser and Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, 149.

[77] Ibid, 149.

[78] Walton, A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, 147.

[79] Ibid, 147.

[80] Ibid, 147.

[81] Baker, The Lives of America’s Suffragists, 214.

[82] Ibid, 148.

[83] Ibid, 148.

[84] The New York Times, “Silent, Silly, and Offensive” and “Militants Get 3 Days; Lack Time to Starve”, American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776 – 1965, ed. by Susan Ware (Literary Classics of the United States, Inc.: New York, 2020), 525.

According to historian and editor Susan Ware, the New York Times published an article the day after the women’s first picket in front of the White House, which was on January 12, 1917. The editors were offering a hypothetical situation of a socialist group picketing in front of the White House and that this “impossible piece of news” being printed “tomorrow morning”, indicating that it would be printed on January 12.

[85] Ibid, 526.

[86] Carrie Chapman Catt, “Carrie Chapman Catt to Frances M. Lane, 14 February 1917”, in A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, ed. by Mary Walton, (Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2010), 154.

[87] Walton, A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, 153.

[88] Ibid, 152.

[89] National Archives, “Voting Rights Act 1965”, Milestone Documents, February 8, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act.

[90] Ibid.