Unseen Fences: How Chicago Built Barriers Inside its Schools

Emily Nicholson

Northern public schools are rarely ever centered in national narratives of segregation. Yet as Thomas Sugrue observes, “even in the absence of officially separate schools, northern public schools were nearly as segregated as those in the south.”[1] Chicago Illustrates this, despite the Jim Crow laws, the city developed a racially organized educational system that produced outcome identical to those segregated in southern districts. The city’s officials celebrated equality while focusing on practices that isolated black students in overcrowded schools. The north was legally desegregated and was not pervasive but put into policies and structures of urban governance.

This paper argues that Chicago school segregation was intentional. It resulted from a coordinated system that connected housing discrimination, political resistance to integration, and targeted policies crafted to preserve racial separation in public schools. While Brown v. Board of Education outlawed segregation by law, Chicago political leaders, school administration, and networks maintained it through zoning, redlining, and administrative manipulation. Using both primary source, newspapers NAACP records, and a great use of historical scholarship, this paper shows how segregation in Chicago was enforced, defended, challenged, and exposed by the communities that it harmed.

Historiography

The historical context outlined above leads to several central research questions that guide this paper. First, how did local governments and school boards respond to the Brown v. Board of Education decision, and how did their policies influence the persistence of segregation in Chicago? Second, how did housing patterns and redlining contribute to the continued segregation of schools? Third, how did the racial dynamics of Chicago compare to those in other northern cities during the same period?

These questions have been explored by a range of scholars. Thomas Surgue’s Sweet Land of Liberty provides the framework for understanding northern segregation as a system put in the local government rather than state law. Sugrue argues that racism in the north was “structural, institutional, and spatial rather than legal, shaped through housing markets, zoning decisions, and administrative policy. His work shows that northern cities constructed segregation through networks of bureaucratic authority that were hard to challenge. Sugrue’s analysis supports the papers argument by demonstrating that segregation in Chicago was not accidental but maintained through everyday decisions.

Philip T.K. Daniel’s scholarship deepens this analysis of Chicago by showing how school officials resisted desegregation both before and after Brown v. Board. In his work A History of the Segregation-Discrimination Dilemma: The Chicago Experience, Daniel shows that Chicago public school leaders manipulated attendance boundaries, ignored overcrowding schools, and defended “neighborhood schools” as the way to preserve racial separation. Daniel highlights that “in the years since 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, research have repeatedly noted that all black schools are regarded inferior.”[2] Underscoring the continuing of inequality despite federal mandates. Daniel’s findings reinforce these papers claim that Chicago’s system was made intentional, and the local officials played a high role in maintaining segregation.

Dionne Danns offers a different perspective by examining how students, parents, and community activists responded to the Chicago public school’s discriminatory practices. In Crossing Segregated Boundaries, her study of Chicago’s High School Students Movement, Danns argues that local activism was essential to expose segregation that officials tied to hide. She shows that black youth did not just fix inequalities of their schools but also developed campaigns, boycotts, sit-ins, which challenged Chicago Public School officials and reshaped the politics of education. Danns’ work supports the middle portion of this paper, it analyzes how community resistance forced Chicago’s segregation practices in a public view.

Paul Dimond’s Beyond Busing highlights how the court system struggled to confront segregation in northern cities because it did not connect with the law. Dimond argues that Chicago officials used zoning, optional areas, intact busing, and boundaries to maintain separation while avoiding the law. He highlights that, “the constant thread in the boards school operation was segregation, not neighborhood,”[3] showing that geographic justification was often a barrier for racial intent. Dimond’s analysis strengthens the argument that Chicago’s system was coordinated and on purpose, built through “normal” administrative decisions.

Jim Carl expands the scholarship into the time of Harold Washington, showing how political leadership shaped the educational reform. Carl argues that Washington believed in improving black schools not through desegregation but through resource equity and economic opportunities for black students. This perspective highlights how entrenched the early segregation policies were, reformers like Washington built a system that was made to disadvantage black communities. While Carl’s focus is later in the Papers period, his work provides the importance of how political structure preserved segregation for decades.

Regional and National Context

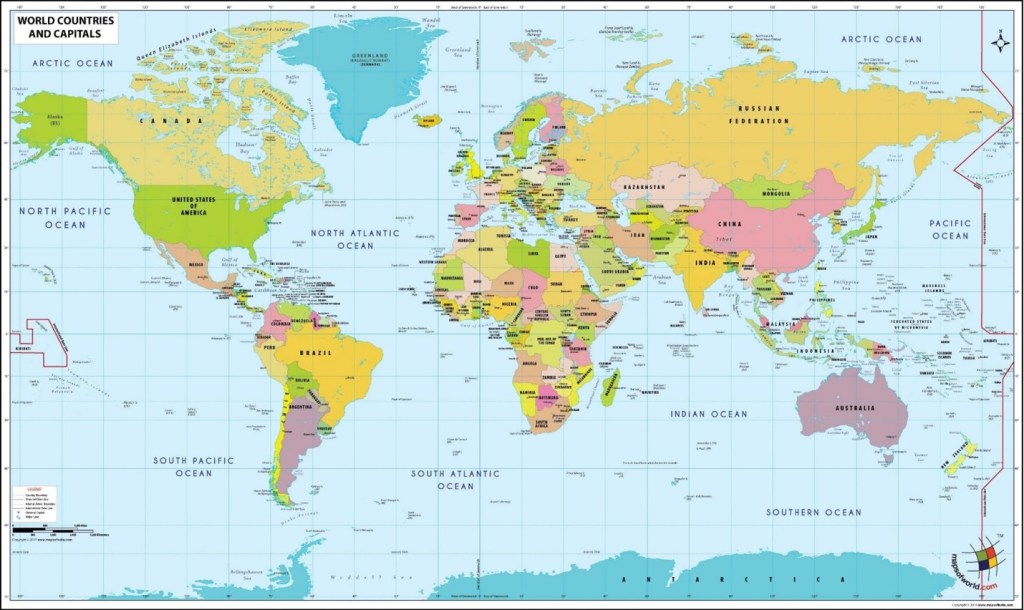

Chicago’s experience with segregation was both typical and different among the northern cities. Cities like Detroit, Philadelphia, and New York faced similar challenges. Chicago’s political machine created these challenges. As Danns explains in “Northern Desegregation: A Tale of Two Cities”, “Chicago was the earliest northern city to face Title VI complaint. Handling the complaint, and the political fallout that followed, left the HEW in a precarious situation. The Chicago debacle both showed HEW enforcement in the North and West and the HEW investigating smaller northern districts.”[4] This shows how much political interest molded the cities’ approach to desegregation, and how federal authorities had a hard time holding the local systems responsible. The issue between the local power and federal power highlighted a broader national struggle for civil rights in the north, and a reminder that racial inequality was not only in one region but in the entire country. Chicago’s challenge highlights the issues of producing desegregation in areas where segregation was less by the law, and more by policies and politics.

Local policy and zoning decisions made segregation rise even more. In Beyond Busing, Paul R. Dimond says, “To relieve overcrowding in a recently annexed area with a racially mixed school to the northeast, the Board first built a school in a white part and then rejected the superintendent’s integrated zoning proposal to open new schools…. the constant thread in the Board’s school operations was segregation, not neighborhood.”3 These decisions show policy manipulation, rather than the illegal measures that maintained separation.

Dimond further emphasizes the pattern: “throughout the entire history of the school system, the proof revealed numerous manipulations and deviations from ‘normal’ geographic zoning criteria in residential ‘fringes’ and ‘pockets,’ including optional zones, discontinuous attendance areas, intact busing, other gerrymandering and school capacity targeted to house only one race; this proof raised the inference that the board chose ‘normal’ geographic zoning criteria in the large one-race areas of the city to reach the same segregated result.”3 These adjustments were hard but effective in strengthening segregation by making sure even when schools were open, the location, and resource issuing meant that black students and white students would have different education environments. The school board’s actions show a bigger strategy for protecting the status quo under the “neighborhood” schools and making it understandable that segregation was not an accident but a policy.

On the other hand, Carl highlights the policy solutions that are considered for promoting integration, other programs which attract a multiracial, mixed-income student body. Redraw district lines and place new schools to maximize integration… busing does not seem to be an issue in Chicago…it should be obviously metro wide, because the school system is 75 percent minority.” [5]. This approach shows the importance of system solutions that go beyond busing, and integration requires addressing the issue of racial segregation in schools. Carl’s argument suggests that busing itself created a lasting change. By changing district lines, it is not just about moving the children around, but to change the issues that reinforce segregation.

Understanding Chicago’s segregation requires comparing northern and southern practices. Unlike the south, where segregation was organized in law, northern segregation was de facto maintained through residential patterns, local policies, and bureaucratic practices. Sugrue explains, “in the south, racial segregation before Brown was not fundamentally intertwined with residential segregation.”1. This shows how urban geography and housing discrimination shaped educational inequality in northern cities. In Chicago, racial restrictive, reddling, confined black families to specific neighborhoods, and that decided which school the children could attend. This allowed northern officials to say that segregation was needed more than as a policy.

Southern districts did not rely on geographic attendance zones to enforce separation; “southern districts did not use geographic attendance zones to separate black and whites.”1. In contrast, northern cities like Chicago used zones and local governance to achieve smaller results. Danns notes, “while legal restrictions in the south led to complete segregation of races in schools, in many instances the north represented de facto segregation, which was carried out as a result of practice often leading to similar results”4. This highlights the different methods by segregation across regions, even after the legal mandates for integration. In the south, segregation was enforced by the law, making the racial boundaries clear and intentional.

Still, advocacy groups were aware of the nationwide nature of this struggle. In a newspaper called “Key West Citizen” it says, “a stepped-up drive for greater racial integration in public schools, North and South is being prepared by “negro” groups in cities throughout the country.” Resistance for integration could take extreme measures, including black children to travel long distances to go to segregated schools, while allowing white children to avoid those schools. In the newspaper “Robin Eagle” it notes, “colored children forced from the school they had previously attended and required to travel two miles to a segregated school…white children permitted to avoid attendance at the colored school on the premise that they have never been enrolled there.” [6] These examples show how resistance to integration represents a national pattern of inequality. Even though activist and civil rights groups fought for the educational justice, the local officials and white communities found ways to keep racial segregation. For black families, this meant their children were affected by physical and emotional burdens of segregation like, long commutes, bad facilities, and reminder of discrimination. On the other hand, white students received help from more funding and better-found schools. These differences show how racial inequality was within American education, as both northern and southern cities and their systems worked in several ways.

Understanding Chicago’s segregation requires comparing northern and southern practices. Unlike the south, where segregation was organized in law, northern segregation was de facto maintained through residential patterns, local policies, and bureaucratic practices. Sugrue explains, “in the South, racial segregation before Brown was not fundamentally intertwined with residential segregation.”1. This shows how urban geography and housing discrimination shaped educational inequality in northern cities. In Chicago, racial restrictive, reddling, confined black families to specific neighborhoods, and that decided which school the children could attend. This allowed northern officials to say that segregation was needed more than as a policy.

Southern districts did not rely on geographic attendance zones to enforce separation; “southern districts did not use geographic attendance zones to separate black and whites.”1 In contrast, northern cities like Chicago used zone and local governance to achieve smaller results. Danns notes, “while legal restrictions in the south led to complete segregation of races in schools, in many instances the north represented de facto segregation, which was carries out as a result of practice often leading to similar results”.4 This highlights the different methods by segregation across regions, even after the legal mandates for integration. In the South, segregation was enforced by the law, making the racial boundaries clear and intentional.

Yet the advocacy groups were aware of the nationwide nature of this struggle. In a newspaper called “Key West Citizen” it says, “a stepped-up drive for greater racial integration in public schools, North and South is being prepared by “negro” groups in cities throughout the country.” Resistance for integration could take extreme measure, including black children to travel long distances to go to segregated schools, while allowing white children to avoid those schools. These examples show how resistance to integration represents a national pattern of inequality. Even though activist and civil rights groups fought for educational justice, the local officials and white communities found ways to keep racial segregation. For black families, this meant their children were affected by physical and emotion burdens of segregation like, long commutes, bad facilities, and reminder of discrimination. On the other hand, white students received help from more funding and better-found schools. These differences show how racial inequality was within American education, as both northern and southern cities and their systems worked in several ways.

The policies that shaped Chicago schools in the 1950’s and 1960’s cannot be understood without looking at key figures such as Benjamin Willis and Harold Washington. Benjamin Willis, who was a superintendent of Chicago Public Schools from 1953 to 1966 and became known for his resistance to integration efforts. Willis’ administration relied on the construction of mobile classrooms, also known as “Willis wagons,” to deal with the overcrowding of Black schools. Other than reassigning students to nearby under-enrolled schools, Willis placed these classrooms in the yards of segregated schools. As Danns explains, Willis was seen by Chicagoans as the symbol of segregation as he gerrymandered school boundaries and used mobile classrooms (labeled Willis Wagons) to avoid desegregation.”4 . His refusal to implement desegregation measures made him a target of protest, including boycotts led by families and students.

On the other hand, Harold Washington, who would become Chicago’s first black mayor, represented a shift towards community-based reform and equality-based policies. Washington believed that equality in education required more than racial integration, but it needed structural investment in Black schools and economic opportunities for Black students. Jim Carl writes, Washington’s approach, “Washington would develop over the next thirty-three years, one that insisted on adequate resources for Black schools and economic opportunities for Black students rather than viewing school desegregation as the primary vehicle for educational improvement.”5 His leadership came from the earlier civil rights struggles of the 1950’s and 1960’s with the justice movements that came in the post-civil rights era.

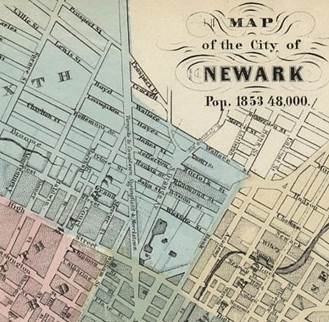

How Chicago Built Segregation

Chicago’s experience in the mid-twentieth century provides an example of how racial segregation was maintained through policy then law. In the postwar era, there was an increase in Chicago’s population. Daniel writes, “this increased the black school population in that period by 196 percent.”4. By the 1950’s, the Second Great Migration influenced these trends, with thousands of Black families arriving from the south every year. As Sugrue notes, “Blacks who migrated Northern held high expectations about education.” 1. There was hope the northern schools would offer opportunities unavailable in the South. Chicago’s public schools soon became the site of racial conflict as overcrowding; limited resources, and administrative discrimination showed the limits of those expectations.

One of the features of Chicago’s educational system is the era of the “neighborhood schools” policy. On paper, this policy allowed students to attend schools near their homes, influencing the community. In practice, it was a powerful policy for preserving racial segregation. Sugrue explains, “in densely populated cities, schools often within a few blocks of one another, meaning that several schools might serve as “neighborhood”.”1. Because housing in Chicago was strictly segregated through redlining, racially restrictive areas, and de facto residential exclusion, neighborhood-based zoning meant that Black and white students were put into separate schools. This system allowed city officials to claim that segregation reflected residential patterns rather than intentional and avoiding the violation of Brown. A 1960 New York Times article called, “Fight on Floor now ruled out” by Anthony Lewis, revealed how Chicago officials publicly dismissed accusations of segregation while internally sustaining the practice. The article reported that school leaders insisted that racial imbalance merely reflected “neighborhood conditions” and that CPS policies were “not designed to separate the races,” even as Black schools operated far beyond capacity.”[7] This federal-level visibility shows that Chicago’s segregation was deliberate: officials framed their decisions as demographic realities, even though they consistently rejected integration measures that would have eased overcrowding in Black schools.

The consequences of these policies became visible by the 1960’s. Schools in Black neighorhoods were overcrowded, operating on double shifts or in temporary facilities. As Dionne Danns describes in Northern Desegregation: A Tale of Two Cities, she says, “before school desegregation, residential segregation, along with Chicago Public School (CPS) leaders’ administrative decisions to maintain neighbor-hood schools and avoid desegregation, led to segregated schools. Many Black segregated schools were historically under-resourced and overcrowded and had higher teacher turnover rates.”[8] The nearby white schools had empty classrooms and more modern facilities. This inequality sparked widespread community outrage, setting up the part for the educational protest that would define Chicago’s civil rights movement.

The roots of Chicago’s school segregation related to its housing policies. Redlining, the practice by which federal agencies and banks denied loans to Black homebuyers and systematically combined Black families to certain areas of the city’s south and west sides. These neighborhoods were often shown by housing stock, limited public investment, and overcrowding. Due to this policy, school attendance zones were aligned with neighborhood boundaries, these patterns of residential segregation were mirrored with the city’s schools. As historian Matthew Delmont explains in his book, Why Busing Failed, this dynamic drew the attention of federal authorities: “On July 4, 1965, after months of school protest and boycotts, civil rights groups advocated in Chicago by filing a complaint with the U.S. Office of Education charging that Chicago’s Board of Education violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”[9] This reflected how much intertwined housing and education policies were factors of racial segregation. The connection between where families could live and where their children could attend school showed how racial inequality was brought through everyday administrative decisions, and molding opportunities for generations of black Chicagoans.

These systems, housing, zoning, and education helped maintain a racial hierarchy under local control. Even after federal courts and civil rights organizations pushed for compliance with Brown, Chicago’s officials argued that their schools reflect demographic reality rather than discriminatory intent. This argument shows how city planners, developers, and school administrators collaborated. School segregation was not a shift from southern style Jim Crow, but a defining feature of North governance.

Resistance and Exposure

Chicago’s struggle with school segregation was not submissive. Legal challenges and community activism were tools in confronting inequalities. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund filed many lawsuits to challenge these policies and targeted the districts that violated the state’s education law. Parents and students organized boycotts and protests and wanted to draw attention to the injustices. Sugrue notes, “the stories of northern school boycotts are largely forgotten. Grassroots boycotts, led largely by mothers, inspired activists around the country to demand equal education”1. The boycotts were not symbolic but strategic; community driven actions targeted at the system’s resistance to change. These movements represented an assertion of power from communities that had to be quiet by discriminatory policies. Parents, especially black mothers, soon became figures in these campaigns, using their voices, and organizing ways to demand responsibility from school boards and city officials. Their actions represented the change that would not come straight from the courtrooms, but from the people affected by injustice. The boycotts interrupted the normal school system and forced officials to listen to the demands for equal education.

Danns emphasizes the range of activism during this period, writing in Chicago High School Students’ Movement for Quality Public Education: “in the early 1960’s, local and prominent civil rights organizations led a series of protests for school desegregation. These efforts included failed court cases, school boycotts, and sit-ins during superintendent Benjamin Willis administration, all which led to negligible school desegregation”[10]. Despite the limited success of these efforts, the activism of the 1960’s was important for exposing the morals of northern liberalism, and the continuing of racial inequalities outside the South. Student-led protests and communities organizing, not only challenged the policies of the Chicago Board of Education but also influenced the new generation for young people to see education as a main factor in the struggle for civil rights.

Legal tactics were critical in enforcing agreements. An article from the NAACP Evening Star writes, “on the basis of an Illinois statute which states that state-aid funds may be withheld from any school district that segregated based on race or color.” [11]The withholding of state funds applied pressure on resistant boards, showing that legal leverage could have consequences. When the board attempted to deny black students’ admission, the NAACP intervened. In the newspaper “Evening Star”, They reported, “Although the board verbally refused to admit negro students and actually refused to do so when Illinois students applied for admission, when the board realized that the NAACP was going to file suit to withhold state-aid funds, word was sent to each student who had applied that they should report to morning classes.” [12]This shows how legal and financial pressure became one of the effective ways for enforcing desegregation. The threat of losing funds forced the school boards to work with the integration orders, highlighting the appeals were inadequate to undo the system of discrimination. The NAACP’s strategy displayed the importance of defense with legal enforcement, using the courts and states’ statutes to hold them accountable. This illustrated that the fight for educational equality required not only the protest, but also the legal base to secure that justice was to happen. This collaboration of legal action and grassroots mobilization reflects the strategy that raised both formal institutions and community power, showing the northern resistance to desegregation was far from being unchanged.

Long-Term Consequences

Chicago’s segregated schools had long-lasting effects on Black students, particularly through inequalities in the education system. Schools in Black neighborhoods were often overcrowded, underfunded, and provided fewer academic resources than their white counterparts. These disparities limited educational opportunities and shaped students’ futures. The lack of funding meant that schools could no longer afford placement courses, extracurricular programs, or even resources for classrooms, this shaped a gap in the quality of education between and black and white students. Black students in these kinds of environments were faced with educational disadvantages, but also less hope on their future.

Desegregation advocates sought to address both inequality and social integration. Danns explains, “Advocates of school desegregation looked to create integration by putting students of different races into the same schools. The larger goal was an end to inequality, but a by-product was that students would overcome their stereotypical ideas of one another, learn to see each other beyond race, and even create interracial friendships”4. While the ideal of desegregation included fostering social understanding, the reality of segregated neighborhoods and schools often hindered these outcomes. Even when legal policies aimed to desegregate schools, social and economic blockades continued to bring separation. Many white families moved to suburban districts to avoid integration. This created more classrooms to be racially diverse and left many of the urban schools attended by students of color.

The larger society influenced students’ experiences inside schools, despite efforts to create inclusive educational spaces. Danns explains, “In many ways, these schools were affected by the larger society; and tried as they might. Students often found it difficult to leave their individual, parental, or community views outside the school doors”9 Even when students developed friendships across racial and ethnic lines, segregated boundaries persisted: “Segregated boundaries remained in place even if individuals had made friends with people of other racial and ethnic groups”4. The ongoing influence of social norms and expectations meant that schools were not blinded by the racial tensions that existed outside their walls. While the teachers and administration may have tried to bring a more integrated environment, the racial hierarchies and prejudices in the community often influenced the students’ interactions. These hurdles were not always visible, but they shaped the actions within the school in fine ways. Despite the efforts at inclusion, the societal context of segregation remained challenging, and limited the integration and equality of education.

Beyond the social barriers, the practical issue of overcrowding continued to affect education. Carl highlights this concern, quoting Washington: “In interest, Washington stated that the issue ‘is not “busing,” it is freedom of choice. Parents must be allowed to move their children from overcrowded classrooms. The real issue is quality education for all’5. The focus on “freedom of choice” underscores that structural inequities, rather than simple policy failures, were central to the ongoing disparities in Chicago’s schools.

Overcrowding in urban schools was a deeper root to inequality. Black neighborhoods were often left with underfunded and overcrowded schools, while the white schools had smaller classes, and more resources. The expression of “freedom of choice” was meant to show that parents in marginalized communities should all have the same educational opportunity as the wealthier neighborhoods. However, this freedom was limited by residential segregation, unequal funding, and barriers that restricted many within the public school system.

The long-term impact of segregation extended beyond academics into the social and psychological lives of Black students. Segregation reinforced systemic racism and social divisions, contributing to limited upward mobility, economic inequality, and mistrust of institutions. Beyond the classroom, these affects shaped how the black students viewed themselves and where they stand in society. Psychologically, this often resulted in lower self-esteem and no academic motivation. Socially, segregation limited interactions between the different racial groups, and formed stereotypes. Overtime, these experiences came from a cycle in the issue of educational and government institutions, as black communities struggled with inequalities continuously.

Black students were unprepared for the realities beyond their segregated neighborhoods, “Some Black participants faced a rude awakening about the world outside their high schools. Their false sense of security was quickly disrupted in the isolated college towns they moved to, where they met students who had never had access to the diversity they took for granted”9. This contrast between the relative diversity within segregated urban schools and the other environments illustrates how deeply segregation shaped expectations, socialization, and identity formation.

Even after desegregation policies were implemented, disparities persisted in access to quality education. Danns observes that, decades later, access to elite schools remained unequal: “After desegregation ended, the media paid attention to the decreasing spots available at the city’s top schools for Black and Latino students. In 2018, though Whites were only 10 percent of the Chicago Public Schools population, they had acquired 23 percent of the premium spots at the top city schools”7. This statistic underscores the enduring structural and systemic inequalities in the educational system. These inequalities show how racial privilege and access to resources favored by certain groups and disadvantaged others. Segregation has taken new ways, through economic and residential patterns rather than laws. This highlights the policy limitations, and brings out the need for more social, economic, and institutional change to achieve the goal of educational equality.

Segregation not only restricted access to academic resources but also had broader psychological consequences. By systematically limiting opportunities and reinforcing racial hierarchies, segregated schooling contributed to feelings of marginalization and diminished trust in public institutions. The experience of navigating a segregated school system often left Black students negotiating between a sense of pride in their communities and the constraints imposed by discriminatory policies. The lasting effects of these psychological scars were there long after segregation ended. The pain from decades of separation made it hard for many black families to believe in change that brought equality. Segregation was not an organized injustice, but also an emotional one; shaping how generations of students understood their worth, and connection to a system that let them down before.

The structural and social consequences of segregation were deeply intertwined. Overcrowded and underfunded schools have diminished educational outcomes, which in turn limit economic and social mobility. Social and psychological barriers reinforced these disparities, creating a cycle that affected multiple generations. Yet the activism, legal challenges, and community efforts described earlier demonstrate that Black families actively resisted these constraints, fighting for opportunities and equality. Their fight not only challenged the system’s injustice, but also laid a foundation for more civil rights reforms, and influencing future movements.

By examining Chicago’s segregation in the context of broader northern and national trends, it becomes clear that local policies and governance played an outsized role in shaping Black students’ experiences. While southern segregation was often codified in law, northern segregation relied on policy, zoning, and administrative practices to achieve similar results. The long-term impact on Chicago’s Black communities reflects the consequences of these forms of institutionalized racism, emphasizing the importance of both historical understanding and ongoing policy reform.

Conclusion

Chicago’s school segregation was not accidental or demographic, it was a product of housing, political and administrative decisions designed to preserve racial separation. The city’s leaders made a system that mirrored the thinking behind Jim Crow Laws and its legal framework, making northern segregation more challenging to see. Through policies made in bureaucratic language, Chicago Public Schools and city officials made sure that children got unequal education for decades.

The legacy of Chicago’s segregation exposes the character of educational inequality. Although activists, parents, and students fought to expose the challenges and the discrimination they created in the mid-twentieth century to continue to shape educational output today. Understanding the intentional design behind Chicago’s segregation is essential to understanding the persistence racial inequalities that defines American schooling. It is also a call to action reformers today to confront the historical and structural forces that have made these disparities. The fight for equitable education is not just about addressing the present-day inequalities but also dismantling the policies and systems that were built with the purpose of maintaining racial separation. The struggle for equality in education remains unfinished, and by acknowledging the choices that lead to the situation can be broken down by structures that continue to limit opportunities for future generations.

References

Primary Sources

Evening Star. (Washington, DC), Oct. 23, 1963. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83045462/1963-10-23/ed-1/.

Evening Star. (Washington, DC), Oct. 22, 1963. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83045462/1963-10-22/ed-1/.

Evening Star. (Washington, DC), Sep. 8, 1962. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83045462/1962-09-08/ed-1/.

Naacp Legal Defense and Educational Fund. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Records: Subject File, -1968; Schools; and States; Illinois; School desegregation reports, 1952 to 1956, undated. – 1956, 1952. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss6557001591/.

The Robbins eagle. (Robbins, IL), Sep. 10, 1960. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn2008060212/1960-09-10/ed-1/.

The Key West citizen. (Key West, FL), Jul. 9, 1963. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83016244/1963-07-09/ed-1/.

Secondary Sources

Carl, Jim. “Harold Washington and Chicago’s Schools between Civil Rights and the Decline of the New Deal Consensus, 1955-1987.” History of Education Quarterly 41, no. 3 (2001): 311–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/369199.

Dionne Danns. 2020. Crossing Segregated Boundaries: Remembering Chicago School Desegregation. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=a82738b5-aa61-339b-aa8a-3251c243ea76.

Danns, Dionne. “Chicago High School Students’ Movement for Quality Public Education, 1966-1971.” The Journal of African American History 88, no. 2 (2003): 138–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3559062.

Danns, Dionne. “Northern Desegregation: A Tale of Two Cities.” History of Education Quarterly 51, no. 1 (2011): 77–104. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25799376.

Matthew F. Delmont; Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation

Philip T. K. Daniel. “A History of the Segregation-Discrimination Dilemma: The Chicago Experience.” Phylon (1960-) 41, no. 2 (1980): 126–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/274966.

Philip T. K. Daniel. “A History of Discrimination against Black Students in Chicago Secondary Schools.” History of Education Quarterly 20, no. 2 (1980): 147–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/367909.

Paul R. Dimond. 2005. Beyond Busing: Reflections on Urban Segregation, the Courts, and Equal Opportunity. [Pok. ed.]. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=76925a4a-743d-3059-9192-179013cceb31.

Thomas J. Sugrue. Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten struggle for Civil Right in the North. Random House: NY.

[1] Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York: Random House, 2008),

[2] Philip T. K. Daniel, “A History of the Segregation-Discrimination Dilemma: The Chicago Experience,” Phylon 41, no. 2 (1980): 126–36.

[3]Paul R. Dimond, Beyond Busing: Reflections on Urban Segregation, the Courts, and Equal Opportunity (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005)

- [4]Dionne Danns, Crossing Segregated Boundaries: Remembering Chicago School Desegregation (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020)

[5] Jim Carl, “Harold Washington and Chicago’s Schools between Civil Rights and the Decline of the New Deal Consensus, 1955–1987,” History of Education Quarterly 41, no. 3 (2001): 311–43.

[6] The Robbins Eagle (Robbins, IL), September 10, 1960,

[7] The New York Times, “Fight on the Floor Ruled out,” July 27, 1960, 1.

[8] Dionne Danns, “Northern Desegregation: A Tale of Two Cities,” History of Education Quarterly 51, no. 1 (2011): 77–104.

[9] Matthew F. Delmont, Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

[10] Dionne Danns, “Chicago High School Students’ Movement for Quality Public Education, 1966–1971,” Journal of African American History 88, no. 2 (2003): 138–50.

[11] NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Subject File: Schools; States; Illinois; School Desegregation Reports, 1952–1956, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress,

[12] Evening Star (Washington, DC), September 8, 1962,