New York’s Education Wars a Century Ago Show How Content Restrictions Can Backfire

Bill Greer

Reprinted with permission from https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/185878

Matthew Hawn, a high school teacher for sixteen years in conservative Sullivan County, Tennessee, opened the 2020-21 year in his Contemporary Issues class with a discussion of police shootings. White privilege is a fact, he told the students. He had a history of challenging his classes, which led to lively discussions among those who agreed and disagreed with his views. But this day’s discussion got back to a parent who objected. Hawn apologized – but didn’t relent. Months later, with more parents complaining, school officials reprimanded him for assigning “The First White President,” an essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates, which argues that white supremacy was the basis for Donald Trump’s presidency. After another incident in April, school officials fired him for insubordination and unprofessional behavior.

Days later, Tennessee outlawed his teaching statewide, placing restrictions on what could be taught about race and sex. Students should learn “the exceptionalism of our nation,” not “things that inherently divide or pit either Americans against Americans or people groups against people groups,” Governor Bill Lee announced. The new laws also required advance notice to parents of instruction on sexual orientation, gender identity, and contraception, with an option to withdraw their children.

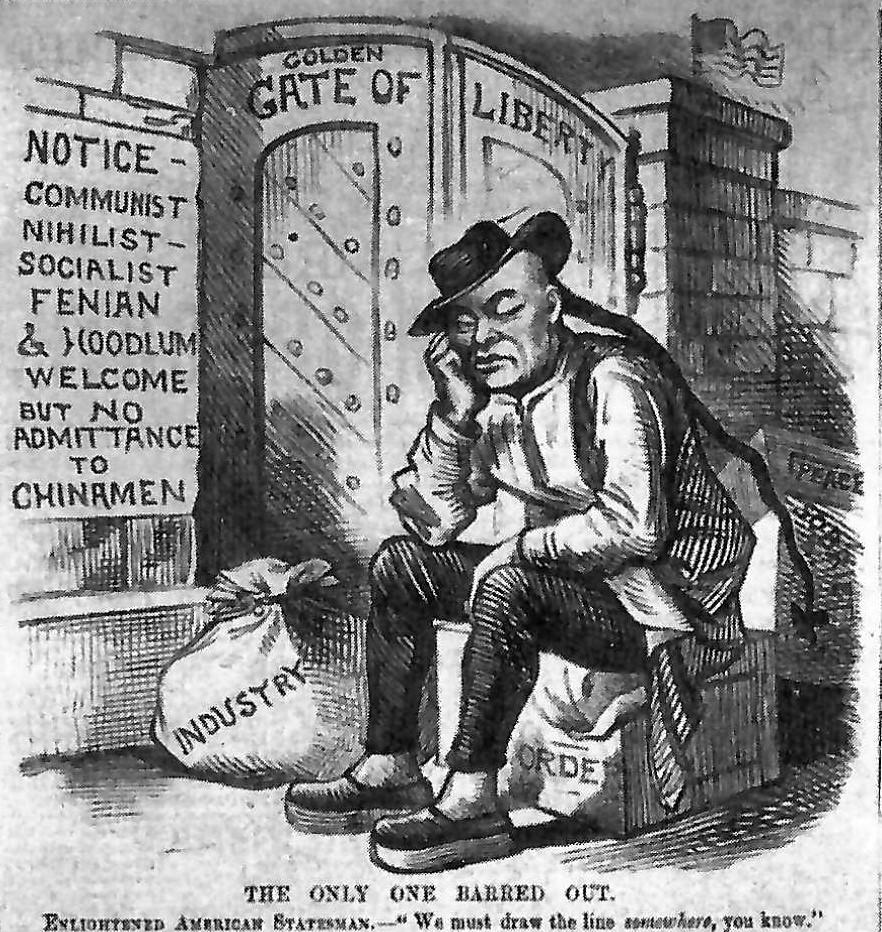

Over the past three years, at least 18 states have enacted laws governing what is and is not taught in schools. Restricted topics mirror Tennessee’s, focusing on race, gender identity, and sexual orientation. In some cases, legislation bans the more general category of “divisive concepts,” a term coined in a 2020 executive order issued by the Trump administration and now promoted by conservative advocates. In recent months, Florida has been at the forefront of extending such laws to cover political ideology, mandating lessons that communism could lead to the overthrow of the US government. Even the teaching of mathematics has not escaped Florida politics, with 44 books banned for infractions like using race-based examples in word problems.

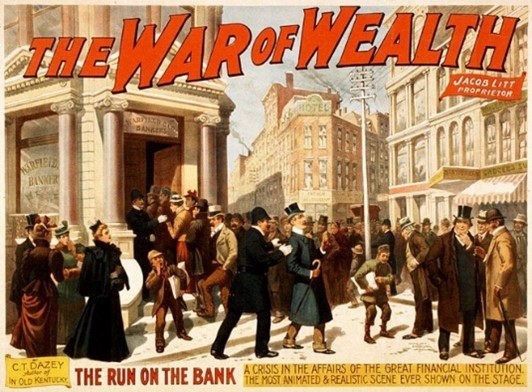

In a sense the country is stepping back a century to when a similar hysteria invaded New York’s schools during the “Red Scare” at the end of World War I, when fear of socialism and Bolshevism spread throughout the US. New York City launched its reaction in 1918 when Mayor John Francis Hylan banned public display of the red flag. He considered the Socialist Party’s banner “an insignia for law hating and anarchy . . . repulsive to ideals of civilization and the principles upon which our Government is founded.”

In the schools, Benjamin Glassberg, a teacher at Commercial High School in Brooklyn, was cast in Matthew Hawn’s role. On January 14, 1919, his history class discussed Bolshevism. The next day, twelve students, about one-third, signed a statement that their teacher had portrayed Bolshevism as a form of political expression not nearly so black as people painted it. The students cited specifics Glassberg gave them – that the State Department forbade publishing the truth about Bolshevism; that Red Cross staff with first-hand knowledge were prevented from talking about conditions in Russia; that Lenin and Trotsky had undermined rather than supported Germany and helped end the war. The school’s principal forwarded the statement to Dr. John L. Tildsley, Associate Superintendent of Schools, who suspended Glassberg, pending a trial by the Board of Education.

Glassberg’s trial played out through May. Several students repeated the charges in their statement, while others testified their teacher had said nothing disrespectful to the US government. Over that period, the sentiments of school officials became clear. Dr. Tildsley proclaimed that no person adhering to the Marxian program should become a teacher in the public schools, and if discovered should be forced to resign. He would be sending to everyone in the school system a circular making clear that “Americanism is to be put above everything else in classroom study.” He directed teachers to correct students’ opinions contrary to fundamental American ideas. The Board of Education empowered City Superintendent William Ettinger to undertake an “exhaustive examination into the life, affiliations, opinions, and loyalty of every member” of the teachers union. Organizations like the National Security League and the American Defense Society pushed the fight against Bolshevism across the country.

After the Board declared Glassberg guilty, the pace picked up. In June, the city’s high school students took a test entitled Examination For High Schools on the Great War. The title was misleading. The first question was designed to assess students’ knowledge of and attitude toward Bolshevism. The instructions to principals said this question was of greatest interest and teachers should highlight any students who displayed an especially intimate knowledge of that subject. The results pleased school officials when only 1 in 300 students showed any significant knowledge of or leaning toward Bolshevism. The “self-confessed radicals” would be given a six-month course on the “economic and social system recognized in America.” Only if they failed that course would their diplomas be denied.

In September, the state got involved. New York Attorney General Charles D. Newton called for “Americanization,” describing it as “intensive instruction in our schools in the ideals and traditions of America.” Also serving as counsel to the New York State Legislative Committee to Investigate Bolshevism, commonly known as the Lusk Committee after its chairman, Newton was in a position to make it happen. In January 1920, Lusk began hearings on education. Tildsly, Ettinger, and Board of Education President Anning S. Prawl all testified in favor of an Americanization plan.

In April, the New York Senate and Assembly passed three anti-Socialist “Lusk bills.” The “Teachers’ Loyalty” bill required public school teachers to obtain from the Board of Regents a Certificate of Loyalty to the State and Federal Constitutions and the country’s laws and institutions. “Sorely needed,” praised the New York Times, a long-time advocate for Americanization in the schools. But any celebration was premature. Governor Alfred E. Smith had his objections. Stating that the Teacher Loyalty Bill “permits one man to place upon any teacher the stigma of disloyalty, and this even without hearing or trial,” he vetoed it along with the others. Lusk and his backers would have to wait until the governor’s election in November when Nathan L. Miller beat Smith in a squeaker. After Miller’s inauguration, the Legislature passed the bills again. Miller signed them in May despite substantial opposition from prominent New Yorkers.

Over the next two years, the opposition grew. Even the New York Times backed off its unrelenting anti-Socialist stance. With the governor’s term lasting only two years, opponents got another chance in November, 1922, in a Smith-Miller rematch. Making the Lusk laws a major issue, Smith won in a landslide. He announced his intention to repeal the laws days after his inauguration. Lusk and his backers fought viciously but the Legislature finally passed repeal in April. Calling the teacher loyalty law (and a second Lusk law on private school licensing) “repugnant to the fundamentals of American democracy,” Smith signed their repeal.

More than any other factor, the experience of the teachers fueled the growing opposition to the Teachers’ Loyalty bill. After its enactment, state authorities administered two oaths to teachers statewide. That effort didn’t satisfy Dr. Frank P. Graves, State Commissioner of Education. In April 1922, he established the Advisory Council on Qualifications of Teachers of the State of New York to hear cases of teachers charged with disloyalty. He appointed Archibald Stevenson, counsel to the Lusk committee and arch-proponent of rooting out disloyalty in the schools, as one member. By summer the Council had earned a reputation as a witch hunt. Its activities drew headlines such as Teachers Secretly Quizzed on Loyalty and Teachers Defy Loyalty Court. Teachers and principals called before it refused to attend. Its reputation grew so bad that New York’s Board of Education asked for its abolishment and the President of the Board told teachers that they need not appear if summoned.

A lesson perhaps lies in that experience for proponents of restrictions on what can be taught today. Already teachers, principals, and superintendents risk fines and termination from violating laws ambiguous on what is and is not allowed. The result has been a chilling environment where educators simply avoid controversial issues altogether. Punishing long-time and respected teachers – like Matthew Hawn, whom dozens of his former students defend – will put faces on the fallout from the laws being passed. How long before a backlash rears up, as it did in New York over Teachers’ Loyalty?