Documenting the 250th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence

Prepared by Fabrizio Caruso and Sofia Sanchez

- Common Sense by Thomas Paine (1776)

- Remember the Ladies by Abigail Adams (1776)

- Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776

- Preamble to the United States Constitution (1787)

- Declaration of the Rights of Man, August 26, (1789)

- Celebrating the Declaration of Independence by John Q. Adams (1821)

- Speech on the Oregon Bill by John C. Calhoun (1848)

- Declaration of Sentiments (1848)

- What to the Slave is the Fourth of July by Frederick Douglass (1852)

- Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln (1863)

- Thirteenth Amendment (1865)

- The New Colossus by Emma Lazarus (1883)

- Release from Woodstock Jail by Eugene V. Debs (1895)

- Nineteenth Amendment (1920)

- Four Freedoms Speech by Franklin Roosevelt (1941)

- The Struggle for Human Rights by Eleanor Roosevelt (1948)

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

- Declaration of Conscience by Senator Margaret Chase Smith (1950)

- Farewell Address by Dwight D. Eisenhower (1961)

- Nation’s Space Effort by John F. Kennedy (1962)

- I Have a dream by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1963)

- Civil Rights Act (1964)

- Bicentennial Ceremony by Gerald R. Ford (1976)

- The Hill We Climb by Amanda Gorman (2021)

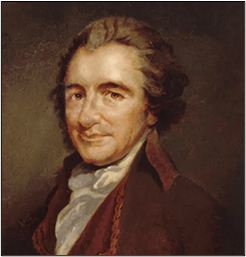

Common Sense – Thomas Paine, January 10, 1776

Thomas Paine published Common Sense anonymously in a pamphlet in 1776. In it, he called for independence from Great Britain, which was a foreign idea at the time. He argued that his claims were common sense and that breaking away from the rule of Great Britain was a necessity for the good of the colonists.

In the following pages I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense…

I have heard it asserted by some, that as America has flourished under her former connection with Great-Britain, the same connection is necessary towards her future happiness, and will always have the same effect. Nothing can be more fallacious than this kind of argument. We may as well assert that because a child has thrived upon milk, that is never to have meat, or that the first twenty years of our lives is to become a precedent for the next twenty. But even this is admitting more than is true; for I answer… that America would have flourished as much, and probably much more, had no European power taken any notice of her. The commerce by which she hath enriched herself are the necessaries of life, and will always have a market while eating is the custom of Europe.

But she has protected us, say some… We have boasted the protection of Great Britain, without considering, that her motive was interest not attachment… This new World hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe… As Europe is our market for trade, we ought to form no partial connection with any part of it…

Europe is too thickly planted with Kingdoms to be long at peace, and whenever a war breaks out between England and any foreign power, the trade of America goes to ruin, because of her connection with Britain… There is something absurd, in supposing a Continent to be perpetually governed by an island…

Where, say some, is the king of America? I’ll tell you, Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the royal brute of Great Britain… So far as we approve of monarchy… in America the law is king…

A government of our own is our natural right… Ye that oppose independence now, ye know not what ye do: ye are opening the door to eternal tyranny. . .

Questions:

- How does Paine compare America to a child? How does this compare to the situation of America wanting independence?

- Why is Great Britain protecting America, according to Paine?

- What happens to America whenever Great Britain is at war? Why?

- According to Paine, who is the king of America?

- What does Paine say of people who are opposing independence?

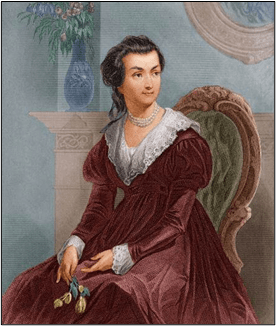

“Remember the Ladies” – Abigail Adams, March 31, 1776

Abigail Adams was the wife of revolutionary and second president John Adams. She herself fought for the rights of colonists and advocated for equal rights for women in a time where this was uncommon. In one of her frequent letters to John Adams, she urged him to “remember the ladies” as he was working on the initial draft to the Declaration of Independence. Ultimately, the wording of the Declaration of Independence was exclusionary and women did not receive equal rights until the twentieth century.

Tho we felicitate ourselves, we sympathize with those who are trembling least the Lot of Boston should be theirs. But they cannot be in similar circumstances unless pusillanimity and cowardise should take possession of them. They have time and warning given them to see the Evil and shun it. — I long to hear that you have declared an independancy — and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies, we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex. Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness.

Questions:

- What is Abigail Adams asking of John Adams?

- What does Abigail Adams believe of all men?

- Why must men pay attention to the ladies, according to Adams?

Declaration of Independence – July 4, 1776

On July 4, 1776, the most important foundational document in the history of the United States was approved by the Second Continental Congress. The Declaration of Independence, penned by Thomas Jefferson, outlined a formal “declaration” of the 13 colonies as an independent, sovereign state that had broken away from the British Crown and listed various grievances that the new country had against the King. Jefferson scattered the document with political and social ideological thought that would become ingrained principles of American government and society.

“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government…”

Questions:

- What are the three “unalienable Rights” Thomas Jefferson identifies?

- According to Jefferson, what must the people do if a government fails to safeguard these unalienable Rights?

- In your opinion, has the U.S. government upheld the message and liberties outlined in the Declaration of Independence. Explain.

Preamble to the Constitution, 1787

Once the United States declared its independence from Great Britain, the nation’s founders needed a stronger, more structured set of laws for government. The initial Articles of Confederation were weak and did structure the government in a way that would be sustainable. Thus, the Constitution was formed after deliberation at the Constitutional Convention. The Preamble serves as the introduction to the Constitution as a whole and establishes the tone and goals for this new budding nation.

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Questions:

- What is the importance of the first three words of the Constitution?

- List the six goals outlined in the Constitution.

- Why was it important for the United States to write the Constitution after the Articles of Confederation?

- Select one of the goals of the Constitution. Why do you think the authors believed it was important to include the goal that you chose?

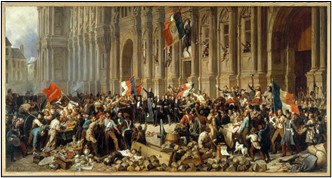

“Declaration of the Rights of Man” – National Assembly of France, August 26, 1789

Just a few years after the end of the American Revolution, France was experiencing a revolution of their own. The Third Estate had become overwhelmingly frustrated by the poverty, stagnant economic growth, inept leadership, and poor quality of life they faced while the First and Second Estates lived in luxury and prosperity. The newly formed National Assembly released the Declaration of the Rights of Man in the midst of this violent revolution.

“The representatives of the French people, organized as a National Assembly, believing that the ignorance, neglect, or contempt of the rights of man are the sole cause of public calamities and of the corruption of governments, have determined to set forth in a solemn declaration the natural, unalienable, and sacred rights of man, in order that this declaration, being constantly before all the members of the Social body, shall remind them continually of their rights and duties…Therefore the National Assembly recognizes and proclaims, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following rights of man and of the citizen:

Articles:

1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

2. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, and security, and resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

…7. No personal shall be accused, arrested, or imprisoned except in the cases and according to the forms prescribed by law. Any one soliciting, transmitting, executing, or causing to be executed, any arbitrary order, shall be punished.

…9. As all persons are held innocent until they have been declared guilty…

10. No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.

11. The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights…

Questions:

- According to the preamble, what is the purpose of this declaration?

- In the context of the French Revolution, why is the wording of “equal in rights” significant?

- Discuss the extent in which this declaration compares to the Declaration of Independence?

- How do the two declarations define the rights guaranteed to all men?

“Celebrating the Declaration of Independence” –John Quincy Adams, July 4, 1821

While serving as Secretary of State under President James Monroe, John Quincy Adams was invited to Congress to give a speech to commemorate the 45th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Adams spends much of this speech praising the Declaration and commending the Founding Fathers’ bravery and triumph over the British Crown in establishing the new nation. This speech has become synonymous with the idea of “American exceptionalism.”

“…In the long conflict of twelve years which had preceded and led to the Declaration of Independence, our fathers had been not less faithful to their duties, than tenacious of their rights. Their resistance had not been rebellion. It was not a restive and ungovernable spirit of ambition, bursting from the bonds of colonial subjection; it was the deep and wounded sense of successive wrongs, upon which complaint had been only answered by aggravation, and petition repelled with contumely, which had driven them to their last stand upon the adamantine rock of human rights.

…It was the first solemn declaration by a nation of the only legitimate foundation of civil government. It was the cornerstone of a new fabric, destined to cover the surface of the globe. It demolished at a stroke the lawfulness of all governments founded upon conquest. It swept away all the rubbish of accumulated centuries of servitude.

…It will be acted o’er [over], fellow-citizens, but it can never be repeated. It stands, and must forever stand alone, a beacon on the summit of the mountain, to which all the inhabitants of the earth may turn their eyes for a genial and saving light, till time shall be lost in eternity, and this globe itself dissolve, nor leave a wreck behind. It stands forever, a light of admonition to the rulers of men; a light of salvation and redemption to the oppressed…so long shall this declaration hold out to the sovereign and to the subject the extent and the boundaries of their respective rights and duties; founded in the laws of nature and of nature’s God. Five and forty years have passed away since this Declaration was issued by our fathers; and here are we, fellow-citizens, assembled in the full enjoyment of its fruits.”

Questions:

- What does John Quincy Adams say the Declaration of Independence was the “first” declaration to do?

- Why does Adams call the American Revolution a “resistance,” not a “rebellion?”

- Why does Adams call the Declaration a “beacon on the summit of the mountain?”

- Do you agree with Adams’ perspective of the revolution and the Declaration? Explain.

“Speech on the Oregon Bill” – Senator John C. Calhoun, June 27, 1848

As the nation crept closer to an impending Civil War, American politics became engulfed over the issue of slavery. One of the leading voices of the pro-slavery movement was South Carolina Democrat senator John C. Calhoun. After serving as Andrew Jackson’s vice president, he ended his career in the Senate. There, he was one of the Democratic Party’s most outspoken supporters for “states’ rights” to defend and uphold slavery within its borders. This speech was in response to the Oregon Bill, which was set to outlaw slavery practices in the new Oregon territory.

“The proposition to which I allude, has become an axiom in the minds of a vast majority on both sides of the Atlantic, and is repeated daily from tongue to tongue, as an established and incontrovertible truth; it is, that “all men are born free and equal.” I am not afraid to attack error, however deeply it may be entrenched, or however widely extended, whenever it becomes my duty to do so, as I believe it to be on this subject and occasion.

Taking the proposition literally (it is in that sense it is understood), there is not a word of truth in it. It begins with “all men are born,” which is utterly untrue. Men are not born. Infants are born. They grow to be men. And concludes with asserting that they are born “free and equal,” which is not less false. They are not born free. While infants they are incapable of freedom, being destitute alike of the capacity of thinking and acting, without which there can be no freedom. Besides, they are necessarily born subject to their parents, and remain so among all people, savage and civilized, until the development of their intellect and physical capacity enables them to take care of themselves…

If we trace it back, we shall find the proposition differently expressed in the Declaration of Independence. That asserts that “all men are created equal.” The form of expression, though less dangerous, is not less erroneous…

… [G]overnment has no right to control individual liberty beyond what is necessary to the safety and well-being of society. Such is the boundary which separates the power of government and the liberty of the citizen or subject in the political state, which, as I have shown, is the natural state of man—the only one in which his race can exist, and the one in which he is born, lives, and dies.”

Questions:

- What does Senator Calhoun say about the phrase “all men are created equal?”

- According to Calhoun, how should the government’s role be limited?

- What is the connection that Senator Calhoun makes between liberty and race? What does this mean about his message in this speech?

Declaration of Sentiments – Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention, 1848

At the Women’s Rights Convention in 1848, 68 women and 32 men signed the “Declaration of Sentiments”, which was essentially a Bill of Rights for women. The document called for equal social, civil, and political liberties for women, which included the right to vote, equal education opportunities, and more legal protections. Elizabeth Cady Stanton served as the primary author as well as Lucretia Mott and Martha Coffin Wright. The Declaration of Sentiments was modeled after the Declaration of Independence, which was written just 72 years prior.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. […]

“The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world. He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise. He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice. He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men – both natives and foreigners. Having deprived her of this first right as a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides. He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead. He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns. […]

“Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation, – in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.”

Questions:

- What other document is the introduction to the Declaration of Sentiments modeled after?

- What is the purpose of this excerpt of the Declaration of Sentiments?

- List two of the grievances that the authors included.

- Do you believe that this declaration is convincing enough to help women gain equal rights? What would you change if anything?

“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” – Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland in 1818. He escaped slavery in 1838 and used his tutoring of the English language to become a renowned orator and writer. He used the strength of his words to call for the abolition of slavery and worked to ensure freedom for all enslaved people. This speech was written to encourage people to think about what the Fourth of July means for those in America who are not free and who do not experience the same rights and opportunities as their White counterparts.

“This, for the purpose of this celebration, is the 4th of July. It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom . . . There is consolation in the thought that America is young […] The simple story of it is, that, 76 years ago, the people of this country were British subjects . . . You were under the British Crown . . . But, your fathers . . . They went so far in their excitement as to pronounce the measures of government unjust, unreasonable, and oppressive, and altogether such as ought not to be quietly submitted to […] Citizens, your fathers made good that resolution. They succeeded; and to-‐day you reap the fruits of their success. The freedom gained is yours; and you, therefore, may properly celebrate this anniversary. The 4th of July is the first great fact in your nation’s history—the very ring-‐bolt in the chain of your yet undeveloped destiny.

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour. Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the every day practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival […]

“Allow me to say, in conclusion . . . I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation, which must inevitably, work the downfall of slavery. “The arm of the Lord is not shortened,” and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.”

Questions:

- What words does Douglass use that show he does not align with free Americans?

- How is the fourth of July different for enslaved people and free people? Use one example from the text.

- How does Douglass conclude his speech? Why do you think he feels this way?

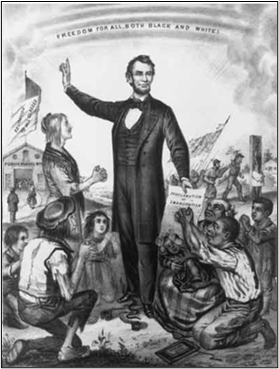

“Gettysburg Address” – Abraham Lincoln, November 19, 1863

Between July 1 and 3, 1863, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War took place in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Both the Union and Confederacy faced catastrophic losses, with casualties totaling over 50,000 men. The Battle of Gettysburg remains the deadliest battle of American history. Four months later, President Abraham Lincoln arrived at Gettysburg to declare the battlefield as a national cemetery. Many in the crowd were anticipating a long speech from President Lincoln, however this famous address only lasted about 3 minutes. Nevertheless, the Gettysburg Address would become enshrined as one of Lincoln’s, and U.S. history’s, most powerful speeches.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

…But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate–we can not consecrate–we can not hallow–this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us–that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion–that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain–that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom–and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Questions:

- According to Lincoln, what is the “proposition” that the nation was founded on?

- What is this civil war “testing?”

- What is Lincoln’s tone throughout the speech? Use at least two pieces of textual evidence to support your response.

- How does President Lincoln use ideas from the Declaration of Independence in this speech? To what extent is it effective? Use at least two pieces of textual evidence to support your response.

Thirteenth Amendment, 1865

The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States. Slavery had been an institution in the United States since the first ship holding enslaved people arrived from the shores of Africa in 1619. Prior to the entire United States abolishing slavery, some states had already dismantled the system of slavery. Many became champions for the abolition of slavery and helped enslaved people escape to freedom. The amendment was ratified in December 1865 after being passed by Congress in January 1865. The Thirteenth Amendment serves as the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments. While it ended legal slavery, Southern states later used the “punishment for crime” clause to create “Black Codes”, which prevented Black people from voting and limited their rights.

“Section 1

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

“Section 2

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Questions:

1. What did the thirteenth amendment accomplish?

2. Where is involuntary servitude still legal?

3. Who has the power to enforce the thirteenth amendment?

4. Do you believe that it is justified for involuntary servitude to be used for criminal offenders? Why or why not?

The New Colossus – Emma Lazarus, 1883

Emma Lazarus was an American poet who wrote the poem “The New Colossus” in 1883. When writing this sonnet, she was inspired by the Statue of Liberty and what the statue represents. In 1903, this poem was engraved onto a bronze plaque and is now on the base of the Statue of Liberty in New York.

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Questions:

- How does Emma Lazarus describe the Statue of Liberty in the poem? Use one line from the text that supports your answer.

- What group of people might lines 10-14 be referring to? How do you know?

- Why is it appropriate that Emma Lazarus’s poem “The New Colossus” appears on the base of the Statue of Liberty?

“Speech on Release from Woodstock Jail” – Eugene V. Debs, November 22, 1895

Eugene V. Debs was one of the nation’s leading critics of big business and corporations. He was an adamant socialist and sought to educate workers to unionize to combat malicious business practices by their employers. In 1893, there was a massive strike organized against the Pullman Sleeping Car Company. Debs helped organize a boycott with the American Railway Union. President Grover Cleveland had sent the U.S. military to handle the strike, and Debs was later arrested for federal contempt and conspiracy charges.

“Manifestly the spirit of ‘76 still survives. The fires of liberty and noble aspirations are not yet extinguished. I greet you tonight as lovers of liberty and as despisers of despotism. I comprehend the significance of this demonstration and appreciate the honor that makes it possible for me to be your guest on such an occasion. The vindication and glorification of American principles of government, as proclaimed to the world in the Declaration of Independence, is the high purpose of this convocation.

Speaking for myself personally I am not certain whether this is an occasion for rejoicing or lamentation. I confess to a serious doubt as to whether this day marks my deliverance from bondage to freedom or my doom from freedom to bondage…It is not law nor the administration of law of which I complain. It is the flagrant violation of the Constitution, the total abrogation of law and the usurpation of judicial and despotic power, by virtue of which my colleagues and myself were committed to jail, against which I enter my solemn protest; and any honest analysis of the proceedings must sustain the haggard truth of the indictment.

In a letter recently written by the venerable Judge Trumbull that eminent jurist says: “The doctrine announced by the Supreme Court in the Debs case, carried to its logical conclusion, places every citizen at the mercy of any prejudiced or malicious federal judge who may think proper to imprison him.”. .

The theme tonight is personal liberty; or giving it its full height, depth, and breadth, American liberty, something that Americans have been accustomed to eulogize since the foundation of the Republic, and multiplied thousands of them continue in the habit to this day because they do not recognize the truth that in the imprisonment of one man in defiance of all constitutional guarantees, the liberties of all are invaded and placed in peril.

Questions:

- What ideas is Debs referencing when he says “the spirit of ‘76 still survives?”

- What rights does Debs claim the government has taken away from him and/or denied?

- Do you agree with Debs’ analysis of the situation he faced during the Pullman Strike? Explain your answer using evidence from the speech.

Nineteenth Amendment, 1920

From the founding of the United States, women have been championing for equal rights and the ability to vote. From Abigail Adams calling for John Adams to “remember the ladies” to the suffragettes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, women and their allies had been calling for equal opportunities since America’s inception. In 1920, the nineteenth amendment was ratified and women were guaranteed the right to vote.

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

“Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Questions:

- What did the nineteenth amendment accomplish?

- Who holds the power to enforce this amendment?

Do you think that any women were prevented from voting following the 19th amendment? Who? Why?

“Four Freedoms Speech” – President Franklin D. Roosevelt, January 6, 1941

As World War II engulfed Europe, President Roosevelt and the U.S. government navigated the tightrope of effective foreign policy. The United States had long held a strong position of isolationism, and many Americans were firmly opposed to any involvement in Europe’s second world war. However, the U.S. government had shifted away from its isolationism by the end of the 1930s. FDR’s State of the Union address in 1941 echoed a new dawn of American interventionism, as he outlined the four freedoms everybody in the world was entitled to.

“Since the permanent formation of our Government under the Constitution, in 1789, most of the periods of crisis in our history have related to our domestic affairs. Fortunately, only one of these–the four year War Between the States–ever threatened our national unity. Today, thank God, one hundred and thirty million Americans, in forty-eight States, have forgotten points of compass in our national unity.

…In like fashion from 1815 to 1914–ninety-nine years–no single war in Europe or in Asia constituted a real threat against our future or against the future of any other American nationf…In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression–everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way–everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want–which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants–everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear–which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor–anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very anthesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.”

Questions:

- What does FDR say has been the reason for (most) periods of crisis in U.S. history? Why is the current situation in Europe (World War II) different?

- What are the four freedoms FDR lists in this speech?

- In your opinion, do people “everywhere in the world” experience the four freedoms today? Explain your answer.

“The Struggle for Human Rights” – Eleanor Roosevelt, 1948

Eleanor Roosevelt was the first lady of the United States from 1933-1945 while her husband, Franklin D. Roosevelt, was president. She redefined the role by speaking out often and calling attention to important social issues. Her speech “The Struggle for Human Rights” was given at the United Nations, to which she served as a delegate to its General Assembly, where she served as chair of the commission that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

We must not be confused about what freedom is. Basic human rights are simple and easily understood: freedom of speech and a free press; freedom of religion and worship; freedom of assembly and the right of petition; the right of men to be secure in their homes and free from unreasonable search and seizure and from arbitrary arrest and punishment. We must not be deluded by the efforts of the forces of reaction to prostitute the great words of our free tradition and thereby to confuse the struggle. Democracy, freedom, human rights have come to have a definite meaning to the people of the world which we must not allow any nation to so change that they are made synonymous with suppression and dictatorship…

The basic problem confronting the world today, as I said in the beginning, is the preservation of human freedom for the individual and consequently for the society of which he is a part. We are fighting this battle again today as it was fought at the time of the French Revolution and at the time of the American Revolution. The issue of human liberty is as decisive now as it was then. I want to give you my conception of what is meant in my country by freedom of the individual…

Indeed, in our democracies we make our freedoms secure because each of us is expected to respect the rights of others and we are free to make our own laws…

Basic decisions of our society are made through the expressed will of the people. That is why when we see these liberties threatened, instead of falling apart, our nation becomes unified and our democracies come together as a unified group in spite of our varied backgrounds and many racial strains…

It is my belief, and I am sure it is also yours, that the struggle for democracy and freedom is a critical struggle, for their preservation is essential to the great objective of the United Nations to maintain international peace and security…

The future must see the broadening of human rights throughout the world. People who have glimpsed freedom will never be content until they have secured it for themselves. In a true sense, human rights are a fundamental object of law and government in a just society. Human rights exist to the degree that they are respected by people in relations with each other and by governments in relations with their citizens.

Questions:

- What are the basic human rights that Eleanor Roosevelt claims are “simple and easily understood”?

- What does Roosevelt say makes freedom secure?

- In your opinion, why are freedom and democracy essential for all people?

“Universal Declaration of Human Rights” – United Nations, December 10, 1948

Following the end of World War II, the victorious European powers and the United States created a new global organization to govern international affairs. The United Nations was created to replace the failed League of Nations, and serve as the leading world institution to maintain peace, protect human rights, and prevent future wars and conflict. One of the first declarations of the United Nations was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Below are Articles 1 through 7 of the UDHR.

Article 1

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and the security of person.

Article 4

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Article 5

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Article 6

Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

Article 7

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

Questions:

- Identify three (3) rights that are guaranteed by the UDHR.

- According to Article 2, what kinds of “distinctions” are prohibited from deny people their rights?

- Which phrases of ideas in the UDHR connect to the Declaration of Independence?

- How does the UDHR expand on the phrase “all men are created equal?”

- In your opinion, does the world today uphold these human rights? Explain.

Declaration of Conscience – Senator Margaret Chase Smith (1950)

In June 1950, in the midst of an anti-communist campaign identified with Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin), Senator Margaret Chase Smith (R-Maine) spoke out against “selfish political exploitation” targeting innocent people and threatening basic American rights.

“I would like to speak briefly and simply about a serious national condition. It is a national feeling of fear and frustration that could result in national suicide and the end of everything that we Americans hold dear. It is a condition that comes from the lack of effective leadership either in the legislative branch or the executive branch of our government. … I speak as a Republican. I speak as a woman. I speak as a United States senator. I speak as an American. … I think that it is high time for the United States Senate and its members to do some real soul searching and to weigh our consciences as to the manner in which we are performing our duty to the people of America and the manner in which we are using or abusing our individual powers and privileges. I think that it is high time that we remembered that we have sworn to uphold and defend the Constitution. I think that it is high time that we remembered that the Constitution, as amended, speaks not only of the freedom of speech, but also of trial by jury instead of trial by accusation.”

Whether it be a criminal prosecution in court or a character prosecution in the Senate, there is little practical distinction when the life of a person has been ruined.

“The Basic Principles of Americanism”

Those of us who shout the loudest about Americanism in making character assassinations are all too frequently those who, by our own words and acts, ignore some of the basic principles of Americanism –

The right to criticize.

The right to hold unpopular beliefs.

The right to protest.

The right of independent thought.

The exercise of these rights should not cost one single American citizen his reputation or his right to a livelihood nor should he be in danger of losing his reputation or livelihood merely because he happens to know someone who holds unpopular beliefs. Who of us does not? Otherwise none of us could call our souls our own. Otherwise thought control would have set in.

The American people are sick and tired of being afraid to speak their minds lest they be politically smeared as “Communists” or “Fascists” by their opponents. Freedom of speech is not what it used to be in America. It has been so abused by some that it is not exercised by others. The American people are sick and tired of seeing innocent people smeared and guilty people whitewashed.”

Questions:

1. What is the national feeling identified by Senator Smith?

2. What does she want American leaders to do?

3. What basic rights does Senator Smith believe are threatened?

4. In your opinion, why did Senator Smith focus on “The Basic Principles of Americanism”?

Farewell Address – President Dwight D. Eisenhower, January 17, 1961

On January 17, 1961, President Eisenhower delivered a ten-minute farewell to the American people on national television from the Oval Office of the White House. In the speech, Eisenhower warned that a large, permanent “military-industrial complex,” an alliance between the military and defense contractors, posed a threat to American democracy.

“We now stand ten years past the midpoint of a century that has witnessed four major wars among great nations. Three of these involved our own country. Despite these holocausts America is today the strongest, the most influential and most productive nation in the world. Understandably proud of this pre-eminence, we yet realize that America’s leadership and prestige depend, not merely upon our unmatched material progress, riches and military strength, but on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.”

Throughout America’s adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations. To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people. Any failure traceable to arrogance, or our lack of comprehension or readiness to sacrifice would inflict upon us grievous hurt both at home and abroad.

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction. … Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United State corporations. … This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence – economic, political, even spiritual – is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted.”

Questions:

1. According to President Eisenhower, why does the United States need to maintain a strong military?

2. Why is President Eisenhower concerned about a “military-industrial complex”?

3. What does President Eisenhower alert the American people to do?

“The Nation’s Space Effort” – President John F. Kennedy, September 12, 1962

Five years prior, the Soviet Union had successfully launched Sputnik 1 into orbit, sparking the beginning of the Space Race between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. The United States quickly sought to catch up to the Soviet Union’s many “firsts” in the Space Race (first satellite, first man in space, first man to orbit the Earth, etc.). Then, in September 1962, President Kennedy gave a speech at Rice University discussing the new goal for America’s space program: put a man on the Moon before the end of the decade.

“…We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war. I do not say the we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.

There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again. But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.”

Questions:

- Why does President Kennedy say it is important to “set sail on this new sea?”

- What justification does President Kennedy give that the United States should be the first nation to conquer space?

- How does Kennedy’s vision for space reflect the ideals in the founding documents?

“I Have a Dream” (from the March on Washington) — Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., August 28, 1963

On August 28, 1963, in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, civil rights leaders and organizations planned a momentous rally in Washington, D. C. Officially known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, over 200,000 people gathered to protest and advocate for the end of segregation and guarantee of civil rights for African Americans. At the end of the march, at the Lincoln Memorial, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., one of the Civil Rights Movement’s most influential leaders, delivered his most famous speech.

“…It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual…

…We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only…

…So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.”

Questions:

- How does Dr. King describe the current situation of African Americans in 1963?

- Why does Dr. King call 1963 “not an end, but a beginning?”

- What founding document does Dr. King reference in this speech? Why does he reference this document?

- In your opinion, has the “dream” described in this speech been achieved? Explain.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

On July 2, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. This act called for desegregation of public spaces, schools, and made voting free and fair for all. This was the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. The act made segregation illegal but it also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to enforce laws that prohibit discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability, or age in hiring, promoting, firing, setting wages, testing, training, apprenticeship, and all other terms and conditions of employment.

To enforce the constitutional right to vote, to confer jurisdiction upon the district courts of the United States to provide injunctive relief against discrimination in public accommodations, to authorize the Attorney General to institute suits to protect constitutional rights in public facilities and public education, to extend the Commission on Civil Rights, to prevent discrimination in federally assisted programs, to establish a Commission on Equal Employment Opportunity, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That this Act may be cited as the “Civil Rights Act of 1964”.

TITLE I: No person acting under color of law shall … apply any standard, practice, or procedure different from the standards, practices, or procedures applied under such law or laws to other individuals within the same county, parish, or similar political subdivision who have been found by State officials to be qualified to vote; deny the right of any individual to vote in any Federal election because of an error or omission on any record or paper relating to any application, registration, or other act requisite to voting … employ any literacy test as a qualification for voting in any Federal election unless (i) such test is administered to each individual and is conducted wholly in writing…

TITLE II: All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, and privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any place of public accommodation, as defined in this section, without discrimination or segregation on the ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.

All persons shall be entitled to be free, at any establishment or place, from discrimination or segregation of any kind on the ground of race, color, religion, or national origin, if such discrimination or segregation is or purports to be required by any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, rule, or order of a State or any agency or political subdivision thereof…

Questions:

- What era of history led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964?

- What does Title I of the Civil Rights Act pertain to?

- What caused Title I to be necessary?

- What is the goal of Title II?

- Why do you believe that the Civil Rights Act was essential?

Bicentennial Ceremony at the National Archives – President Gerald R. Ford, July 2, 1976

On August 9, 1974, President Richard Nixon had resigned from the presidency following the disastrous Watergate scandal. Gerald Ford, Nixon’s vice president, assumed the office immediately and pardoned Nixon one month later. The entire Watergate scandal and Nixon’s resignation created great disdain against the U.S. government. Many Americans became extremely untrustworthy of elected officials and had little faith in the government. Becoming President during the bicentennial of the U.S., Ford dealt with difficult challenges both domestically and abroad.

“The Declaration is the Polaris of our political order–the fixed star of freedom. It is impervious to change because it states moral truths that are eternal.

The Constitution provides for its own changes having equal force with the original articles. It began to change soon after it was ratified, when the Bill of Rights was added. We have since amended it 16 times more, and before we celebrate our 300th birthday, there will be more changes…

Jefferson’s principles are very much present. The Constitution, when it is done, will translate the great ideals of the Declaration into a legal mechanism for effective government where the unalienable rights of individual Americans are secure. In grade school we were taught to memorize the first and last parts of the Declaration. Nowadays, even many scholars skip over the long recitation of alleged abuses by King George III and his misguided ministers. But occasionally we ought to read them, because the injuries and invasions of individual rights listed there are the very excesses of government power which the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and subsequent amendments were designed to prevent…

But the source of all unalienable rights, the proper purposes for which governments are instituted among men, and the reasons why free people should consent to an equitable ordering of their God-given freedom have never been better stated than by Jefferson in our Declaration of Independence. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are cited as being among the most precious endowments of the Creator–but not the only ones.”

Questions:

- What role does President Ford say the Constitution has in relation to the Declaration?

- Why does President Ford say it is important to read the grievances listed against King George III in the Declaration?

- Do you agree with President Ford that the Declaration is unchanging while the Constitution changes over time? Explain your answer.

“The Hill We Climb” – Amanda Gorman, 2021

This poem was read at the inauguration of President Joseph Biden in 2021 by its author, Amanda Gorman. She is a poet, activist, and author who wrote this poem for the inauguration under the theme of “America United”.

…We, the successors of a country and a time where a skinny black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother can dream of becoming president only to find herself reciting for one. And, yes, we are far from polished, far from pristine, but that doesn’t mean we are striving to form a union that is perfect, we are striving to forge a union with purpose, to compose a country committed to all cultures, colors, characters and conditions of man.

So we lift our gazes not to what stands between us, but what stands before us. We close the divide because we know to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside. We lay down our arms so we can reach out our arms to one another, we seek harm to none and harmony for all…

That is the promise to glade, the hill we climb if only we dare it because being American is more than a pride we inherit, it’s the past we step into and how we repair it. We’ve seen a force that would shatter our nation rather than share it. That would destroy our country if it meant delaying democracy, and this effort very nearly succeeded. But while democracy can periodically be delayed, but it can never be permanently defeated.

In this truth, in this faith, we trust, for while we have our eyes on the future, history has its eyes on us, this is the era of just redemption we feared in its inception we did not feel prepared to be the heirs of such a terrifying hour but within it we found the power to author a new chapter, to offer hope and laughter to ourselves, so while once we asked how can we possibly prevail over catastrophe, now we assert how could catastrophe possibly prevail over us. We will not march back to what was but move to what shall be, a country that is bruised but whole, benevolent but bold, fierce and free, we will not be turned around or interrupted by intimidation because we know our inaction and inertia will be the inheritance of the next generation, our blunders become their burden. But one thing is certain: if we merge mercy with might and might with right, then love becomes our legacy and change our children’s birthright.

So let us leave behind a country better than the one we were left, with every breath from my bronze, pounded chest, we will raise this wounded world into a wondrous one, we will rise from the golden hills of the West, we will rise from the windswept Northeast where our forefathers first realized revolution, we will rise from the lake-rimmed cities of the Midwestern states, we will rise from the sunbaked South, we will rebuild, reconcile, and recover in every known nook of our nation in every corner called our country our people diverse and beautiful will emerge battered and beautiful, when the day comes we step out of the shade aflame and unafraid, the new dawn blooms as we free it, for there is always light if only we’re brave enough to see it, if only we’re brave enough to be it.

Questions:

- Why does Amanda Gorman urge readers to look towards the future?

- What does Gorman believe that being an American includes?

- What is the overall tone of the poem? Cite two quotes that support your answer.