The Forgotten Lessons: The Teaching of Northern Slavery

Andrew Greenstein

In the winter of 2021, a dark discovery took Rider University by storm and sparked a revelation amongst many of the students in attendance. After over a century of being hidden in the darkness, the secret that Rider University was once a slave-owning plantation was revealed to the world. A place of advanced education and diversity was once an institution of oppression. The university has since changed the name of the building from the name of the slave owner, Van Cleve, to the Alumni House. It is important that history not be forgotten, but instead brought to the forefront. The university will not erase the history but rather use it as a way to teach about the complicated history of slavery in the state of New Jersey[1]. To many of the students attending the university, this came as a surprise. The students who were history majors were astonished by the fact that slavery occurred in the state of New Jersey, let alone on Rider University’s property. The reason for this lack of information stems from the collective lack of education on the subject.

With a basic understanding of American history, one would be led to believe that slavery was a southern issue and continues to be a contentious history when taught in those states. The reality was that slavery was a nationwide institution. Though schools in the south are vocal about the unwillingness to teach the subject, schools in the north are silent. There is continuous hypocrisy in deflecting all discussions of the matter to the south while ignoring what happened in their own backyards. Walking through any school teaching U.S. history, one may hear a line like “The north were free states and the south were slave states.” Similarly, worded statements can be found within schools in New Jersey all across the state. It implies that Northern states had no slaves at the time of the civil war and were actively fighting the good fight. When the 14th Amendment comes into discussion, one may have the impression that it directly pertained to the freeing of enslaved people in the south, rather than the north as they were already free. This simplification of the issue is far from the truth. To this day, many students will never learn that slavery took place in the north at all, let alone that New Jersey was the last state to abolish the practice. The nation now celebrates Juneteenth to “commemorate an effective end of slavery in the United States”[2]. The stark reality is that slavery persisted after Juneteenth in the state of New Jersey legally for almost a full year, and illegally for another year. That dark history is often forgotten within classrooms throughout the state of New Jersey and the nation.

The lack of national attention to this critical issue does beg the question of how it happened. Many historians argue that the lack of discussion on the institution of northern slavery was due to the racist beliefs of historians in the 19th and 20th centuries.[3] The voices of those early historians often get blamed for creating the view that slavery was only relevant when discussing the civil war as it was undeniably a major cause[4]. As time progressed, one would assume the material on northern slavery would become more prevalent, however, that is not the case. As the discussion both in the classroom and by historians on the institution of slavery has expanded, northern slavery still remains for the most part absent. The question remains: did this critical part of the establishment of the nation go untaught? The only way to answer that question is by examining the teaching of slavery in New Jersey and the Tri-state area. This will open that gateway to a deeper understanding of how this history could be erased from the collective memory.

Before proceeding, it is imperative to understand what the discussion of the education on northern slavery has been. Though the discussion on northern slavery began in the late 1940s alongside the civil rights movement, the conversation about its absence in the classroom does not begin until 1991 due to a shocking discovery in Manhattan, New York[5]. As the federal government was constructing a 275 million dollar project, they stumbled upon “the largest and oldest collection of colonial-era remains of free and enslaved Africans in the United States, according to the National Park Service”. This discovery of the cemetery caused massive protests to fight the city to halt the construction and the removal of the bodies from the site[6]. Following this event, the New York City public schools began to look for a way to incorporate the material into the class and teach this reality that was just revealed to them[7]. This started a growing push from schools across the nation to try to incorporate this reality.

The conversation on northern slavery would continue over a decade later when Professor Alan Singer of Hofstra University would guest teach in New York City public schools. When teaching less than a mile away from the enslaved African cemetery, most of the students were completely oblivious to the reality that not only were slaves in New York but how the reality of slavery was visible in their own community[8]. Though many decisions on how to tackle such an issue were made to teach this material, over a decade later the students still had no idea about northern slavery. The discussions on the material did not translate into the classroom to a sufficient extent. The debate on how to successfully teach northern slavery in the classroom ensued and ultimately lead to the discussion on how to teach this history appropriately.

The content of northern slavery required a restructuring in order to successfully teach the material. Previously, slavery was only taught at the establishment of European colonies in the New World and before the American Civil War. What this divide does is creates the material into another unit, a separate event rather than a continuous struggle. The 2016 book Understanding and Teaching American Slavery by Bethany Jay and Cynthia Lyerly attempt to illustrate the best organization for discussing the topic and the history of the institution of slavery in classrooms. In their analysis of the history of teaching the institution of slavery, they regard the idea of teaching slavery exclusively at those points during early American Colonization and the Civil War to “severely hinder its importance.”[9] What is the best way to teach the institution of slavery is discussing the enslaved perspective threw out the development of the nation.[10] The benefits of this method allow the longevity of the issue and the hardships faced by those affected to be well articulated amongst the students. This is due to its constant presence and the reminder that liberty and freedom were not for all[11]. This revelation in adding the enslaved perspective to early American history would spark further development in tools and resources to bring northern slavery into the classroom.

An initiative would be enacted to bring northern slavery and the massive scope of the institution of slavery to the forefront. This would come in the form of The New York Times 1619 Project. This resource marks an incredible stride in the conversation on teaching northern slavery. The project’s purpose is “to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative”[12]. This comes out of a series of historians and teachers discussing how the realities and the true institution of slavery were untaught to them in the classroom. The project’s aim is to bring these lost lessons of slavery such as its true cruelty and its widespread adoption throughout the nation, not just exclusively in the south. It is built off of the ideals proposed in Understanding and Teaching American Slavery and other books with the same idea tofollow this notion that slavery is an integral part of the nation as a whole, rather than at specific points in U.S. history[13]. The combination of all these ideas paints a picture of the flaws of the teaching of slavery threw out the nation. The current discussion’s main focus is looking at what is absent in the current classroom. The smaller conversation that pertains to the material taught in the past primarily revolves around racism and the Klan[14]. The discovery of a 1904 textbook that details the brutality of northern slavery pushes back on this notion[15]. It begs the question of whether the subject was truly untaught or if another force was responsible for its absence. Looking at the material present in the classroom in the past may prove an insight into northern slavery’s appeared absence.

An analysis of the classroom material available to students is key to understanding the absence of northern slavery. To find these answers, understanding what material was being taught in classrooms from the 1860s and beyond. A method to understand the content of the classroom is by looking at textbooks. Many school notes and lesson plans have been lost to time, but what remains are textbooks. The work of Dr. Pearcy shows the indicator tool that can be used to understand their effect on the content being taught in schools. He states clearly in his article, “Textbooks are, ultimately, tools, for student use. Their utility can only be measured by the degree to which they offer teachers the opportunity to build student-centered inquiry”[16]. From this notion, we can conclude that textbooks are just an object and a tool for students to use. Their content is meaningless unless given a purpose by the teacher. Everything learned in the classroom is under the teachers’ control and they possess the option to use or discard the textbook. However, textbooks do tell us something else depending on where they are. His research looks at ten different U.S. history textbooks of different authors that are widely adopted and compares their tellings of the Battle of Fort Sumter[17]. After analyzing each of the tellings, an interesting trend occurs. This trend is in the bias of the author and how they pick and choose what details to keep and leave out of the telling of the event. This bias could affect the leanings of anyone reading and coerce their perspective of the events that unfolded. These different depictions of the conflict in different areas can have effects on the material discussed in class or reflect it. Companies such as Pearson publish multiple textbooks by different authors to capitalize mainly on the market, however, what market are they capitalizing on?

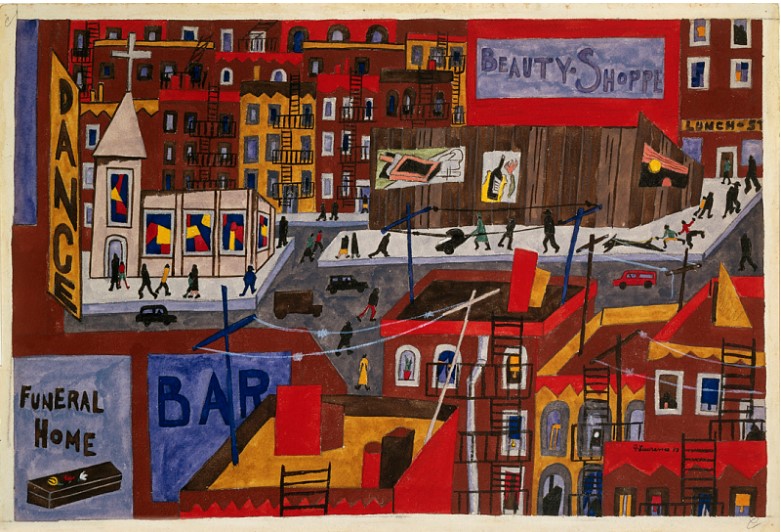

Looking at the rationale behind the variation of textbooks based on location can assist in understanding why certain content is missing. The findings by Goldstein in his article Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories sheds light on the issue of why these publishing companies hire multiple historians and interpretations of the same material. This article focuses on eight different textbooks found within the states of Texas and California. The issues arise when looking at the same textbook in multiple states. The textbooks are by the exact same author but have different versions for each state. The variations were created by request of school districts or even the book’s own editor. These individuals remove or request additions of material to allow the book to be adopted in a particular area[18]. The best evidence to illustrate this divide between locations is that of the Harlem Renaissance. Examples of this are found in Pearson’s United States History: The Twentieth Century 19th edition. On the subject of the Harlem Renaissance, the Californian edition features a section on the debate within the African American community over its overall impact on them and the nation as a whole. The Texas version only includes the line “some critics ‘dismissed the quality of literature produced’”[19]. What these two distinct changes, along with many more, indicate is the presence of the political atmosphere of the area and the belief of the people the textbook is serving to reinforce. The textbook adopted by a particular state or district reflects the information a school is teaching in the classroom.

With an understanding of the behind-the-scenes crafting of textbooks, there can be the formulation of the content of northern slavery in school. Combining the findings of Dr. Pearcy and Goldstein, textbooks can provide insight into the classroom. The selection of the historian and the version adopted by the school reflect what the administration desired its teachers to instruct in the classroom. Though it may not be a perfect indicator of what was taught in classrooms, as it’s a tool for teachers to use, it gives an idea of what is being taught in the classroom. Examining textbooks from the past used in classrooms within the Tristate area can reveal if northern slavery was taught, and to what extent.

Examining the earliest textbook may yield an understanding of the lack of teaching, not only about northern slavery but slavery as a whole. An example of the content of what was taught in the classroom after the Civil War and in the years following can be found in The New England Primer. This book originated in 1690 and was a fixture in the classroom until the 1930s, a well over 200-year run. The textbook served as the basis of elementary education instruction. By looking at these textbook translations, historians get a sense of what was required of the majority of students at this time, along with what was taught in classrooms. Looking at the 1802 edition, the book opens with an alphabet chart. This gets taught through prayers that become progressively more complex as they go[20]. This information indicates that understanding the alphabet was key. Depending on the quantity available, the school could have focused on reading and potentially writing to utilize this book. Within the context of these prayers, one learns about the calendar and days of the week, counting and basic mathematics, and a small amount of history[21]. This stresses the importance of religion in the classroom at this time. The underlying message throughout the book is that God is more important than any other subject or material in the classroom. The small amount of history included is more biblical in nature but does include the basics of the American government system[22]. The addition of the U.S. system of government is the only change from the 1773 edition, replacing prayers outlining the functions and structure of the parliament system[23]. What this shows is that history was really not a focus in this era of education. Only those who would exceed the basic knowledge of the time would learn about more advanced information. With the perpetuation of this book into the 20th century, this basic education would be what was taught to many poor American individuals and black Americans. More fortunate areas would receive new textbooks and educational material, phasing this material out or relying on it less exclusively. Those less fortunate areas would be using this information exclusively until the 1930s. The New England Primer is referred to as the “Bible of one-room schoolhouse education”[24]. The lack of history not only assists in the loss of the knowledge of northern slavery but of the entire institution of slavery as a whole. These individuals would want the history they learned as children in school. A slow creep of this altered history would make its way to the north.

Movements were made to suppress and remove the teaching of not only northern slavery but all of black history. The most prominent of these would be “The Lost Cause”, the movement to honor the legacy of the confederacy. This movement would begin in the 1870s as reconstruction would begin to fail. The lost cause mentality would paint the black community as unable to attain the same equality as white individuals due to the efforts attempting to create equality failed[25]. This gave rise to the notion that the confederates were noble in their sacrifice to fight for slavery. It rewrites the telling of the history that “there was nothing ‘lost’ about the southern cause”[26]. This was due to the mindset that black Americans were only good at being servants to white men. Monuments and memorials to honor the confederacy would be constructed such as the statues of Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, and Robert E. Lee. By the 1890s this movement would sink its teeth into the education system of the north. The goal was to rewrite history books to reflect the southern perspective and preserve its honor. This movement is regarded as a reunion of America’s racist mentality as it proposed the Civil War was caused by other factors, not slavery. It also created this idea of the “happy slave”, the idea that there were enslaved individuals that loved slavery and serving the white man[27]. Women’s organizations and the state department of education were the ones in charge of advocating for approving educational material for schools. Many became strong supporters of the lost cause and by the 1920’s it would be integrated into schools across the north and especially in New Jersey[28].

Before the alteration of the history would appear, strides were made to bring the history of northern slavery to the forefront. In the 1870s history books began to include slavery within their content. The oldest examined history textbook to bear mention of slavery is the Condensed History of The United States from 1871. This book was used in a classroom in Norristown, Pennsylvania, as demonstrated by the address of the school on the front cover pages with the initial date of October 31, 1888. On the page adjacent, student names are written, with the last one being 1899, giving the text an eleven-year confirmed usage in the classroom. The cover pages are full of notes made by students long past, however, one stands out amongst the rest. This particular note is a prayer, one found word for word from the 1812 edition of the New England Primer. This detail establishes that in this classroom, the two books were in fact utilized together. This class was learning American history alongside the basics in the New England Primer. The town had the economic resources present to invest in its youth’s education. The students within this town received a higher quality of education than those of poorer communities. However, what did these students learn about not only northern slavery but the institution of slavery as a whole?

This history tells a very interesting version of America’s past, but what is interesting is what is left out. There is no mention of slavery until what they call the “War of Secession” is discussed[29]. The book starts with the discovery of the new world and the establishment of each American state at the time of its publication, but not one mention of slavery till that point. The book does establish that there was northern slavery by directly stating “At the time of adoption of the Constitution, slavery existed in the Northern as well as the Southern States”[30]. It provides an impressive analysis for its time detailing the various legal cases pertaining to slavery such as Dred Scott v. Sanford. There is a fascinating inaccuracy with the passing of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments; as the book details that Johnson was president for their passing. It details that the passing of these amendments was the cause of the issues between the President and the other two branches, rather than Reconstruction. In fact, the only mention of Reconstruction at all is Johnson vetoing the Reconstruction Act of 1865 rather than discussing any of the programs created by it[31]. This alteration to history has two possible reasons for the inaccuracy. The first is more innocent, being in the title of the book “condensed”. Reconstruction not only is a long process and would officially end in 1877. The book was written in 1874 meaning that reconstruction was still ongoing at the time. Writing on its effects could be taken as more speculatory and not factual information as the book attempts to stick exclusively to. The second is the seed of the lost cause making its way into the material. The ideology of the lost cause deemed Reconstruction a failure and did not warrant time discussion. Its omission is telling that this influence was seeping into the education of these students. However, what is most interesting is what it says about how slavery ended in the north. After detailing the increase of southern populations due to the cotton gin, it stated, “In the North, on the other hand, where slave labor was not profitable, slavery soon died out”[32]. It leads to the idea that in the 1850s slavery was extinct in the north, however, the reality was quite different. Slavery was very much alive in the north during the 1850s.

Looking at the history of just New Jersey alone, there is a far different reality of northern slavery from this telling in the textbook. Starting as far back as the 1790s, New Jersey was split over the issue of slavery. Quakers were strongly against it; they interpreted enslaved people as people due to the wording of the constitution. The three-fifths compromise of 1787 also reinforced their claim that enslaved individuals were people. The opposition viewed freedom as an economic catastrophe. The labor force for the majority of the state’s highest-grossing markets were nearly entirely enslaved or indentured servant individuals. They saw that liberation would make the industries of agriculture, ironworking, and factory manufacturing unprofitable. The debate over a compromise began in 1797 but would reach its conclusion in 1804 with the gradual abolition act, also referred to as the “free womb” act[33]. This legislation gave freedom to all enslaved individuals born after July 4th, 1804 on their 21st birthday[34]. This allowed slave owners to have the labor force they needed to make up for the economic loss of abolition and granted enslaved people their freedom at a set point. The average life expectancy of an enslaved individual in New Jersey at this time was forty-one years. This meant that they would likely have had only half their life to live if they even made it to freedom. The act was filled with loopholes that allowed the continuation of slavery in the state well after the projected period of total abolition. The idea was to have all enslaved individuals freed by the 1830s. The issue was with the clause that allowed children born while in the period of the enslavement term were to be placed in the care of the local principality[35]. Principalities were the townships and counties that reside within the State of New Jersey. Many of the individuals in charge of managing the treatment of these children would give them right back into the hands of their masters, making them slaves till their 21st birthday. This is how the enslaved population grew far larger than it was in 1804 by the 1860s[36].

The inaccuracies of the teaching of northern slavery would have disastrous consequences to its very existence by later generations. The pervasive belief that slavery was all but extinct in the north by the 1860s is evidence of the start of the “the amnesia of slavery”[37]. This is a term coined by historian James Gigantino II in his book The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865-1941. What he seeks to illustrate is how Northern states such as New Jersey with such a large and prosperous enslaved population forgot that slavery even occurred in their own backyards. The reason for this was that slavery was looked at as an “insignificant sideshow” in the state. Many northern slaveowners owned only one or two slaves, thus making the reminders of an enslaved past virtually nonexistent to those that were not directly affected by it[38]. What the Condensed U.S. History textbook shows us is this amnesia occurring. In a time when enslaved individuals and their children were very much still alive, their suffering is being forgotten. There is no active backlash as those with the ability to change the material have little to no interest. This early removal of teaching about what occurred beneath these students’ feet will send shockwaves to later generations and reach into the modern classroom.

There would be a push to expand the teaching of northern slavery upon the turn of the century before the influence of the Klan would take hold. This is evident in the textbook Stories of New Jersey by Frank R. Stockton. This book was published in 1896 and the copy analyzed was printed in 1904. The inside cover indicates the book originated from a Princeton classroom before finding its way into the Library of Congress. It is worth noting that this book is back in reproduction and the Amazon description of the book reads that it was “so popular over the years in NJ schools that it has in itself become a part of New Jersey’s history”[39]. This book possesses a unique feature that is exclusive to this book and none other, even textbooks today. This feature is an entire chapter dedicated to the history of enslaved individuals in the state from 1626-1867[40]. What this chapter says about slavery in the state is incredibly unique, especially for its time of publication. The section begins with Dutch settlers bringing enslaved individuals over with them in 1626 to develop the inhospitable land and form their colony. Enslaved individuals were expendable and would do the labor that would normally require a far more physical toll on the body. They became the largest group of workers in the booming iron industry, logging, and of course, the plantations popping up across the land. In 1664, the Dutch surrendered their colonies to the English empire. In this exchange, many changes would appear in the lives of those original settlers, but slavery was not changed[41]. Slavery remained in this state for over 200 years after this point. This early slavery history even includes an entire section on how Perth Amboy, New Jersey, was the slave trade capital in the north and distributed enslaved individuals throughout the northern colonies[42]. This was all true. While other texts around this period ignore this history, this book sought to put a spotlight on it. Following details of the atrocious conditions the enslaved people in the state faced and the lack of large plantations like the south, it noted that large numbers of individuals owned one or two enslaved individuals[43]. This kept slavery as a pivotal force in the community and essential to its economy. If this text was utilized in the classroom to the fullest, many students would have learned a genuine and dark history of the establishment of the state’s institutions. However, this very insightful history becomes inaccurate regarding the abolition of slavery.

The first half of the telling of northern slavery from Stories of New Jersey is remarkable with its depiction of northern slavery for its time, but that narrative falls apart when reaching the abolition of slavery in the state. While it does portray an accurate picture, much of it is far from the truth. The first comes in the debates over the gradual abolition act of 1804. The book describes it as Quakers becoming abolitionists; the three-fifths compromise made their view under the law that these were people, not property, and entitled to the same rights. The opposition saw slavery as an economic necessity as the work they were doing was dangerous. These were undesirable jobs no one wanted to do in their society. This debate over the issue does remain close to the reality that transpired. The text makes a crucial error in stating the gradual abolition bill that allowed the abolition of slavery on one’s twenty-first birthday passed in 1820 rather than 1804[44]. This alteration of the date creates a precedent that the abolition of slavery was far faster and more efficient. It creates the idea that New Jersey’s policy was successful and had no issues with its implementation. Further errors found in the section support this idea that the solution the state implemented was successful. When discussing the results of the act it directly states, “in 1840 there were still six-hundred and seventy-four slaves in the state, and by 1860 only eighteen slaves remained, and these must have been very old”[45]. These numbers couldn’t be further from the truth as slavery was still going strong by the 1850s.

What is missing from the Stories of New Jersey textbook are those who were wrongfully enslaved. The text leaves out the dark reality that a percentage of slavery occurring in the state was children who were supposed to be free. The 1804 Gradual abolition act forced some of the children born to enslaved mothers into a life of enslavement until their twenty-first birthday. The census of children being born from 1804-1835 to exclusively enslaved mothers shows five hundred and forty-one documented children. It is estimated that in the year 1850, while documentation may say two hundred and thirty-six, far more were illegally in service. The text also does not acknowledge the abolition of slavery in its entirety in 1866. The wording makes it appear it ended gradually by 1860 citing the success of the gradual abolition act[46]. This misinformation will impact generations to come as it was the definitive history of the state. It took until 2008 for the New Jersey government to finally formally apologize for its slave-owning past and its failure to step in and end its illegal perpetuation[47]. Though it may not be the most perfect telling of the history, it’s evidence that people were trying to teach the injustice that happened within their state. Slavery was not relegated to a small part of the civil war, rather it merited its own chapter dedicated to the hardships and debate over its abolishment. While this book is making its way into classrooms, so is the Klan. The Klan would attempt to rapidly spread in the education field and in the coming decades as part of its resurgence. This growth would ultimately transform the history of northern slavery.

The Klans’ takeover of northern education and purging of the history of not just northern slavery, but the entire institution is seen within the textbooks of the 1920s. The 1924 textbook An Elementary History of New Jersey by Earle Thomson is dramatically different from the textbook from 1904. What distinguishes this book aside is absolutely no mention of slavery of any kind. This textbook was definitely used within the state, as in the preface the author thanked superintendents and principals who commissioned a book to express their shared view of the truly important history and to add tools that would enhance student understanding[48]. The schools this particular book was used in included Union, Hackensack, Newark, and Westfield[49]. There may have been more schools adopting this book, however, those are unmentioned by the author, and no indication is left on any of the Library of Congress documentation. The book directly states that “children should be taught in some detail the history of their own state and of its part in the development and progress of the country” while omitting a major part of their history[50]. The larger shocking piece is that only the conflict of the Civil War is discussed. There is no lead-up; it just dropped the reader right into the conflict[51]. It appears that only the victory of the war was significant, but not what they were fighting for or even the amendments that followed. This text is pivotal to understanding the shift in the classroom. The lost cause ideology had reached the apex of its hold on the classroom. The removal of all mention of slavery or black Americans was done to illustrate how unimportant the black community was and how futile any action to promote equality was. However, its removal may have been far more purposeful than just a desire to push this lost cause ideology.

The Klan had far larger ambitions than just the omission of slavery from educational material during the 1920s. The book The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition by Linda Gordon sheds light on this exact time period. The Klan was a notorious hate group created in the aftermath of the Civil War but it saw a resurgence in the 1920s. This revived Klan was stronger in the North than in the southern states of the nation and focused on the education system of the time[52]. Their priority was the recruitment of white American youth to continue their organization into the coming generations. This involved integration of the Klan into the material taught in schools. The Klan and those associated with them edited the material to reflect the beliefs of the organization. This makes recruitment easier as the Klan reflects the morals and values secretly supplanted into the minds of susceptible students[53]. This was most evident in the teaching of history in the classroom. Klansmen in positions of authority in schools such as superintendents used their influence to alter texts found in the classroom. This involved the recreation of textbooks to fit their nefarious agenda[54]. The lack of a mention of slavery or even the leadup or aftermath of the civil war in the 1924 textbook is evidence of known involvement. It’s unclear if any of the principals or superintendents credited in the textbook are Klansmen, but the influence is quite evident. The textbook states, “This book is in no sense a complete history of New Jersey, the author hopes that its study may prove an inspiration to the purple to become an upright citizen of his community or state”[55]. The absence of this major time period in the state’s history is done in a way to not invoke question. Unless there is other supplemental material taught in the classroom, the dark history of the state and the nation are removed from the collective memory. This book directly shows how “the amnesia of slavery”[56] occurred not only in the state of New Jersey but across northern states. With the widespread recruitment push for new Klansmen, anyone learning in schools around this time would have no recollection of northern slavery’s existence. All the work in the decades past to bring this history into the classroom has been completely undone. Any book touching on the subject would have to start from scratch if the goals of those behind the book were successful.

Following the end of the Second World War, the U.S. would revisit the teaching of northern slavery. The post-war U.S. began to enter a period of civil rights and reforms as the Truman administration began to assist in the abolishment of segregation. This gets reflected in the 1947 U.S. history textbook American History by Howard Wilson and Wallice Lamb. This textbook is fascinating due to its creation. The book states that the author’s intentions for writing the textbook were to “include history and perspectives from this great nation that have been forgotten or removed over the years”[57]. This indicates that the creation of the book was to teach a history that includes information removed by the Klan and other parties. The authors attempted to devise a history from the ground up that includes lost information including slavery. It kept its promise by including a simplified version of the slave trade and the quantity of forced labor employed. The text also looked into how the institution of slavery was a fundamental part of colonization in the Americas[58]. It may not be the most perfect of tellings as it leaves the atrocities that faced the enslaved individuals out. This is significant as it leaves out the horrors that faced enslaved individuals. It creates the notion that this was a great injustice on the part of the colonists but was not as horrific as the reality of the situation. It keeps the reader, most likely a white student, separated from the event allowing no remorse for the actions of their forefathers to the black community. This was the last instance of slavery mentioned till the causes of the Civil War. There are two chapters dedicated to the development of agriculture and industry in the northern states and the southern states, but there is no mention of slavery whatsoever[59]. What this does is reinforces the idea that slavery was there, but it wasn’t important in the continued development of the nation. The practice of slavery was only significant in establishing a foothold on the land. It makes the institution and the horrors faced by the enslaved people insignificant to economic development. However, coverage of the Civil War period possessed an interesting take on the content.

The 1947 textbooks’ stance on the Civil War and its aftermath indicate a deviation from the stranglehold of the Klan in education. The period leading up to the war has an interesting take on slavery. The text neither condemns nor supports either side of the debate on slavery. It creates this awkwardly neutral state when describing the situation that caused the suffering of so many[60]. This is important as the goal appears to not anger those with sentiment in support of slavery. The author appears to be holding back their opinion on the matter and not getting into depth on the horrific reality. The text does have an allusion to the idea that the northern states either abandoned or abolished the practice. It describes this trope of the north being “abolitionist”, that there was no one within the state that opposed slavery. Following the end of the war, it does something unique to this text. The textbook described the reconstruction period in a way to appear successful rather than what happened in reality. The book described Reconstruction as establishing property in the south with 40 acres and a mule proposition. It describes how many would remain in the south as they were given property. What is also interesting is that it discusses the surge of newly freed black individuals getting into office as they finally received the right to vote. The book describes the downfall of the reconstruction as due to irresponsible spending of tax dollars and the creation of the Klan forcing black Americans to stay out of government and politics[61]. The text portrays the Klan as the villain in reconstruction. It signifies a shift in public opinion and the elimination of their grasp on the education system. Information that pushes back on the lost cause narrative by showing that Reconstruction was sabotaged is making its way into schools. The neutral dialog however does indicate their presence is still there. The Klans’ limited presence is also indicated by the book leaving out many important details such as lynchings, or even the Great Migration of Black Americans to the north for work. These events had the potential to paint the Klan that existed at this time rather than the early organization during the reconstruction era in a negative light. The Klan may not have been as strong as they were in the previous decades, but was still a prominent organization throughout the nation, especially in the north. The textbooks telling of slavery does reinforce the notion that slavery was exclusively a southern problem, but this is not the first time this will occur.

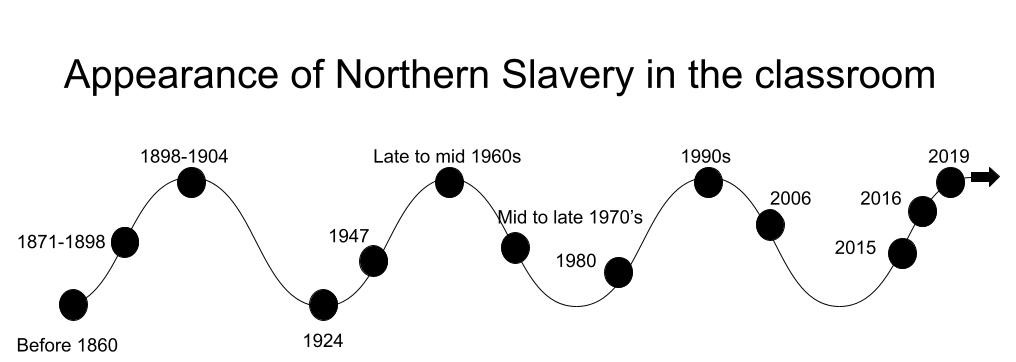

Northern slavery’s absence in the classroom may not have been excluded due to racist involvement in the material. The relegation to slavery being exclusively southern is an issue that perpetuates to this modern day. This trend is one that Mr.Vikos, a former high school history teacher is very familiar with the pattern of returning to relegating slavery to exclusively the south. Mr. Vikos taught in Brooklyn from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. His insight into the teaching of northern slavery illustrates how racism is not the only factor in the removal of this information. In the late 60s, his school was facing a large influx of black students due to the end of segregation in 1963. The school would become nearly 100% black by 1975 and the teachers wanted to teach material that reflected the classroom’s demographics. This involved teaching northern slavery when the pre-Civil War era would arise in the classroom. “Students did enjoy the content at first, but as the years went on there were an increasing number of issues. The first was general confusion as students would get confused on what side slavery was on during the actual conflict. The second and most important issue was the lack of care. The students had no interest in learning about slavery that occurred here (New York)”[62]. Eventually the teaching of northern slavery would be reduced as issues with the content would arise. “Readings on northern slavery were present in the classroom, but the likelihood anyone of the students remembered them a decade later is highly unlikely”[63]. The teaching of northern slavery was present, but students would be the driving factor in its reduction. Eventually, the material would return to the idea that the north were free states and the south was slave states. There is a cycle of the subject of northern slavery appearing and then disappearing. The topic becomes introduced, it reaches a height where the issue is really focused on, and then an outside force acts, reducing the discussion back to the beginning. This trend can be seen between the textbooks from 1874 to 1924 with the Klan removing the material and again from 1947 to the 1970s when student interest would reduce its discussion. This trend would continue into the modern day. This becomes evident with the current lack of understanding of northern slavery even though the material is now present in almost every classroom in northern schools. The decades from the 1980s to the mid-2010s only serve to continue this trend.

To prove this theory of the teaching of northern slavery being a cycle, the decade of the 1980s serves as a point to see the material reintroduced. The 1980 textbook American History Review Text by Irving Gordon illustrates an interesting trend in the telling of history. This book was used in Port Richmond High School in Staten Island, New York throughout the 1980s and into the early 90s. The textbook immediately began with the colonization of America and the triangle trade after establishing a background on the New World. It also does a fantastic job of illustrating the population differences between the enslaved population and the white Europeans[64]. This detail is that “slavery was found as a common practice throughout all English thirteen colonies”[65].Through discussing early American slavery, the inclusion that it existed within the entirety of the nation does allow the student reading to understand that the institution of slavery was in fact present in the north. Continuing the traditional organization structure, the textbook only mentions slavery only at the colonization of America and prior to the Civil War. This structure continues to assist in undermining the severity and longevity of the institution of slavery. When it begins to discuss the pre-Civil war era, it does call out hypocrisy. Though it may be two paragraphs, it sheds light on the hypocrisy of northern slavery[66]. This hypocrisy was the north participating in slavery while simultaneously vilifying the south for participating in the exact same practice. This is significant as this is the first textbook examined to touch upon this issue. Not only does it bring to light northern slavery, but the textbook condemns the north for criticizing southern slavery before it abolished the practice fully within its states. Upon reaching the point of reconstruction, the textbook’s messages begin to shift.

Though time long since passed the time of Klan involvement, the telling of the history still bears its scars. The language of the text leads to assumptions with the vocabulary used to describe the black community at different points. In the beginning, they were described as “Africans” who then transitioned into being referred to as “enslaved” individuals. In the years during reconstruction, they are referred to as “Black”. However, once reconstruction ends they become “negros”[67]. What this shows is the perpetuation of the lost cause mentality through the vocabulary. The idea of referring to black individuals as “negros” in this text is to establish the notion that the black community during the point of reconstruction and after are two different kinds of people. There also are present many allusions to what is going on in the north but the reality is vastly different. An example of this is the education system constructed in the south during Reconstruction. It stated “Negros, as well as whites, were guaranteed free compulsory public education by the reconstruction constitutions of the southern states. However, after the southern whites regained control, Negros received schooling that was segregated and inferior”[68]. This line does highlight the notion that there was segregation and inferior education in the south but makes it appear that it was not a problem in the north. Segregated schools were prominent in the north as well and in some cases persisted far longer than they were legally able to. What this wording does that becomes commonplace is make the south sound like a racist and discriminatory place and paint the northern states in a light that is far from the reality that existed. The textbook does a decent job of illustrating the regression of the discussion of northern slavery. It may establish the institution existed in the north, but it lacks descriptions of the conditions. The text also regresses to race-charged wording linking its connection to the history of previous Klan-influenced textbooks. This would change as the nation entered the 1990s.

The discussion on northern slavery would continue due to its prioritization. The 90s would be a point where the material on northern slavery would begin to grow once again. Starting in 1996, Mr.Vikos would be responsible for approving textbooks for schools in the central headquarters. When asked about the criteria for what textbooks got approved, he would respond with the topic of slavery. He recalled how “many textbooks would just have a paragraph or two on the subject of slavers as a whole. It is impossible to cover all of the slavery in a single book, how do you do it in one paragraph? A textbook would only get passed if it discussed the social, political, and economic factors of both the north and the south”[69]. He would stress the economic section as this would be the deciding factor of slavery’s perpetuation for both the north and the south. What was illustrated was a reinvigoration of the content. This was an individual who was passionate about bringing this information to the classroom and was in a place to do so. With the discovery of the massive burial of enslaved individuals in Manhattan a few years prior, there was a draw into teaching northern slavery.

As time progresses into the modern day, the pattern of the rise and fall of northern slavery’s discussion in the classroom only becomes more rapid of a cycle. Three different versions of the American Pageant textbook by Thomas Bailey, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen illustrate the perpetuation of the rise and fall of northern slavery in the classroom. The editions in question are the 2006, 2013, and 2016 versions. What makes these books unique is that they are currently in use in schools in New Jersey. The ones examined were in the possession of students actively using them in the classroom. What makes this even more interesting is the parts that were changed. The beginning chapters detail the triangle trade and the enslavement of the native American populations and the African populations. It even includes how slavery reach the American colonies in 1619 from captured slaves en route to Spanish colonies diverted to Virginia[70]. The wording is almost exactly word for word between editions, so uniform it’s almost conspicuous. The differences become starkly relevant when the discussion of American slavery comes to question.

The three discussed American Pageant textbooks present differences that illustrate the increase and decline of the topic of northern slavery. Each book possessed a section dedicated to slavery between the founding of the nation and the civil war, slavery prior to the civil war, and a chapter on reconstruction. The differences become apparent in the first few paragraphs of the section. The 2006 edition was altered to include a deeper perspective of northern slavery following the revelation that attempts to include the material were unsuccessful. This is evident as the edition remarked that in the north there was freedom being attained, but there was more hatred of black Americans than in the south[71]. This gets reinforced by the story of an individual who was born enslaved in the south, sold in New York City, and was eventually freed after eight years of servitude and the conditions she lived in after gaining freedom. The textbook accurately portrayed the conditions of slavery, and by covering the north before the south in the description of slavery, it gives the impression that slavery was equally horrible in practice throughout the nation[72]. The 2013 edition states that northern slavery was just small farms with no large-scale plantations. It goes into detail about how New York abolished all of its slavery and possessed far better-living conditions than the south[73]. This entirely changes the established narrative that slavery was a horrible practice. The text almost glorifies the practice of slavery in the state of New York. The 2016 edition resolves these issues by taking the best aspects of the two together. It largely emphasizes the story of the enslaved woman by giving it its own dedicated page[74]. It includes an interesting insight into the northern slavery perspective. It does an excellent job of discussing how “few northerners were prepared for the outright abolition of slavery”. It goes in-depth at looking at the economic issues facing the north if it were to abolish slavery and the general view of the population wanting reform rather than abolition[75]. The description of the popular view of the time feeds into a clearer understanding of the northern hypocrisy. This being the desire to abolish slaves in the south rather than within their own borders. The combining of the best of the two prior editions is the greatest strength of the sixteenth edition. Due to its publication date, the revised text containing a large amount of northern slavery material could be due to the political climate in 2016. The contentious political election sought to reinvigorate the discussion of slavery, especially that of northern states. This may be only speculation due to the recentness of this change, but outside forces like that are indicators of material like this being reintroduced based on the previously analyzed patterns in the earlier textbooks discussed. The three different textbooks indicate a falling point in the 2006 edition due to the reinvigoration in the 90s, a low point in 2015 as northern slavery was no longer in style, and then a spike in 2016 due to a shifting political climate.

What the analysis of these texts indicate is a disturbing trend of periodically increasing and decreasing the teaching of northern slavery in the northern states. There are large and periodic appearances of this under-discussed material and it appears to almost be predictable.

We begin to see it untaught in the classroom in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War[76]. This was due to the material being largely sourced from the New England Primer, a book that focused on basic language, mathematics, and civic education[77]. The exclusivity of this textbook would fuel the “lost cause” ideology. This ideology was the belief that the south was justified in fighting for slavery as reconstruction failed, proving black individuals could never be equal to their white counterparts[78].The discussion of northern slavery begins to increase in the mid-1870s based on the material from Condensed U.S. History from 1874. Though the description of events leads much of the history of northern slavery out, it does make its appearance known[79]. Entering the 20th century we see a boom in the discussion of the material. In the textbook of the history of New Jersey, Stories of New Jersey, there is a detailed history of slavery in the state. It goes as far back as the Dutch and only gets slightly inaccurate in the end with the eventual abolition of the institution[80]. This revolutionary discussion of the material comes crashing down in the 1920s. This is illustrated by the 1924 textbook An Elementary History of New Jersey[81]. Its lack of not only the discussion of slavery in the north, but the absence of the entire practice is the ultimate goal of the “lost cause”. It indicates the idea of the Klan using education as a way to indoctrinate young and new members, and this came at the price of editing textbooks to reflect their views on society[82]. Textbooks and educational material would bear the scars from this alteration for dedicated to come.

The coming age of civil rights reform would attempt to distance itself from the past. The restructuring of this discussion of northern slavery is illustrated in the 1947 textbook American History[83]. Its limited appearance shows that the topic once again rose into the discussion. From the perspective of a history teacher from the late 60s to the mid-1970s, coverage began to increase once again to a clear point in the late 60s as schools finally began to become more diverse due to an end of segregation. Northern slavery’s discussion then began to fall in the 70s as the civil rights movement would lose its ground in the years following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination[84]. The discussion on northern slavery would reach a low in the 1980s and gets illustrated by the 1980 history textbook American History Review Text. It may call out the North but it shows clear evidence of promoting the “lost cause” mentality due to its racially charged language[85]. The 90’s would see a rise in the discussion of northern slavery again as the discovery of the largest enslaved cemetery in the nation would be found under Manhattan. The depth of the discussion on northern slavery reached a height in 2006 with the American Pageant 13th edition. It includes a detailed section on slavery in New York and that the horrors of slavery were present in the north. It even details how northerners viewed the practice as unjust but did little to nothing to end it within their states while criticizing the south[86]. From this height there is a dramatic fall in the 2013 edition of the same textbook. It led to the idea that slavery was small in the north and that it was far better in conditions than in the south. It also creates the illusion that it was abolished by the 1860s rather than continuing throughout the civil war[87]. Lastly, we see a jump in the discussion emerging in 2016. The American Pageant textbook’s 16th edition rectifies this issue of a decrease in the discussion. It adds material from the 2006 edition and expands on the practice and conditions of northern slavery[88]. It’s unclear what the cause of this shift could be, but one could only speculate it was done out of a response to the changing climates and the increased national discussion on the longevity of the impacts the institution of slavery had on the nation.

With these trends highlighted, it’s important to note that there has never been a steady teaching of the material. Teachers have struggled with finding ways to get the material across without creating unnecessary confusion. The importance of this subject is unparalleled as its atrocities have never truly been righted[89]. The perpetuation of these trends creates a lost history of the horrifying events that unfolded beneath the feet of students. They can adequately describe the atrocities that happened in distant states but are oblivious to the same atrocities that happened only a few miles away. The lack of a focus or understanding of what happened in the backyards of both teachers and students alike truly creates and perpetuates the “the amnesia of slavery”[90].

There is hope however that this continuous issue does get brought to light in the classroom. The awareness on the part of the students and teachers alike can see an end to its repetition. Teachers bringing this issue to the forefront and explaining to students that slavery happened here, and that it goes undiscussed, may inspire students to speak up when this topic is left out. Activism on this issue is key to maintaining its presence in the classroom and that these forgotten lessons never become forgotten again.

References:

Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 13th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2006.

Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 15th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2013.

Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 16th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2016.

Blight, David W. Race, and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001.

Ellis, Nicole. “How the Discovery of an African Burial Ground in New York City Changed the Field of Genetics.” The Washington Post. WP Company, December 20, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/12/20/how-discovery-an-african-burial-ground-new-york-city-changed-field-genetics/.

Gigantino II, James J. “The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865-1941.” New Jersey Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 35–55. 2020, Academic Search Premier doi:10.14713/njs.v6i1.188. Accessed 9/28/22.

Gigantino II, James J. The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey, 1775-1865. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Gigantino II, James J.“‘’The Whole North Is Not Abolitionist’’.” Journal of the Early Republic 34 (3): 411–37. 2014, Academic Search Premier doi:10.1353/jer.2014.0040. Accessed 9/28/22

Goldstein, Dana. “Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories.” The New York Times. The New York Times, January 12, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/01/12/us/texas-vs-california-history-textbooks.html.

Gordon, Irving L. Review Text in American History. New York, NY: AMSCO School Publications, 1980.

Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Jay, Bethany, and Cynthia Lynn Lyerly. Understanding and Teaching American Slavery. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2016.

Lapsansky-Werner, Emma J., Peter B. Levy, Randy Roberts, Alan Taylor, and Kathy Swan. United States History: The Twentieth Century. 19th ed. California. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc., 2019.

Lapsansky-Werner, Emma J., Peter B. Levy, Randy Roberts, Alan Taylor, and Kathy Swan. United States History: The Twentieth Century. 19th ed. Texas. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc., 2019.

Mydland, Leidulf. “The Leg of One-Room Schoolhouses: A Comparative Study of the AME…” European journal of American studies. European Association for American Studies, February 24, 2011. https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/9205.

New Jersey. Laws, Statutes, Etc. An act for the gradual abolition of slavery … Passed at Trenton . Burlington, S. C. Ustick, printer 1804. Burlington, 1804. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.0990100b/.

Nix, Elizabeth, What Is Juneteenth?, History.com, A&E Television Networks, June 19th, 2015, Accessed October 31st, 2022, https://www.history.com/news/what-is-juneteenth

Pearcy, Mark, “We Are Not Enemies”: An Analysis of Textbook Depictions of Fort Sumter at the beginning of the Civil War, The History Teacher, Volume 52 Number 4, Society for History Education, August 2019

Pender, Tori, Slaveowner’s name removed from campus’ alumni house, The Rider News, Rider University, November 17th, 2021, Accessed October 31st, 2022, https://www.theridernews.com/slaveowners-name-removed-from-campus-alumni-house/

Samuel Wood & Sons, Publisher. Beauties of the New-England primer. [New York: Published by Samuel Wood & Sons, 261 Pearl-Street, 1818] Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/10011910/.

Stewart, Nikita. “Why Can’t We Teach Slavery Right in American Schools?” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 19, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/slavery-american-schools.html.

Stockton, Frank R. “Stories of New Jersey.” Amazon. OUTLOOK VERLAG, 2020. https://www.amazon.com/Stories-New-Jersey-Frank-Stockton/dp/0813503698.

Stockton, Frank R. Stories of New Jersey. American book company, 1896. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/01007755/.

Swinton, William. Swinton’s Condensed United States: A Condensed School History of the United States: Constructed for Definite Results in Recitation and Containing a New Method of Topical Reviews. New York, Chicago: Ivinson, Blakeman & Co., 1871.

The Associated Press.“Teachers Shed Light on Slavery in the North.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, March 18, 2006. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna11883116.

The New York Times. “The 1619 Project.” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html.

Thomson, Jay Earle. An elementary history of New Jersey. [New York, Philadelphia, etc. Hinds, Hayden & Eldredge, inc, 1924] Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/24011186/.

Vikos, George and Greenstein, Andrew. Conversation at Marina Cafe, Staten Island NY, November 14th, 2022

Westminster Assembly. The New England primer improved: for the easy attaining the true reading of English, to which is added, the Assembly of Divines, and Mr. Cotton’s catechism. Boston: Printed for and sold by A. Ellison, in Seven-Star Lane, 1773. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/22023945/.

Wilson, Howard E, and Wallice E Lamb. American History. Schoharie, NY: American Book Company, 1947.

Wolinetz, Gary K., When Slavery Wasn’t a Dirty Word in NJ, New Jersey Lawyer, February 15th, 1999

[1] Pender, Tori, Slaveowner’s name removed from campus’ alumni house, The Rider News, Rider University, November 17th, 2021, Accessed October 31st, 2022, https://www.theridernews.com/slaveowners-name-removed-from-campus-alumni-house/

[2] Nix, Elizabeth, What Is Juneteenth?, History.com, A&E Television Networks, June 19th, 2015, Accessed October 31st, 2022, https://www.history.com/news/what-is-juneteenth

[3]Wolinetz, Gary K., When Slavery Wasn’t a Dirty Word in NJ, New Jersey Lawyer, February 15th, 1999

[4] Wolinetz, When Slavery Wasn’t a Dirty Word in NJ

[5] Wolinetz, When Slavery Wasn’t a Dirty Word in NJ

[6] Ellis, Nicole. “How the Discovery of an African Burial Ground in New York City Changed the Field of Genetics.” The Washington Post. WP Company, December 20, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/12/20/how-discovery-an-african-burial-ground-new-york-city-changed-field-genetics/.

[7]Stewart, Nikita. “Why Can’t We Teach Slavery Right in American Schools?” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 19, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/slavery-american-schools.html.

[8] The Associated Press.“Teachers Shed Light on Slavery in the North.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, March 18, 2006. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna11883116.

[9] Jay, Bethany, and Cynthia Lynn Lyerly. Understanding and Teaching American Slavery. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2016. p.32

[10] Jay, Lyerly. Understanding and Teaching American Slavery p.11

[11] Jay, Lyerly. Understanding and Teaching American Slavery p.14-17

[12] The New York Times. “The 1619 Project.” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html. P.1

[13] Jay, Bethany, and Cynthia Lynn Lyerly. Understanding and Teaching American Slavery. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2016.

[14] Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001.

[15] Stockton, Frank R. Stories of New Jersey. American book company, 1896. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/01007755/.

[16]Pearcy, Mark, “We Are Not Enemies”: An Analysis of Textbook Depictions of Fort Sumter at the beginning of the Civil War, The History Teacher, Volume 52 Number 4, Society for History Education, August 2019, p.611

[17] Pearcy, “We Are Not Enemies”: An Analysis of Textbook Depictions of Fort Sumter at the beginning of the Civil War, p.596

[18] Goldstein, Dana. “Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories.” The New York Times. The New York Times, January 12, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/01/12/us/texas-vs-california-history-textbooks.html.

[19] Goldstein, “Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories.”

[20]Samuel Wood & Sons, Publisher. Beauties of the New-England primer. [New York: Published by Samuel Wood & Sons, 261 Pearl-Street, 1818] Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/10011910/.p.1-32

[21] Samuel Wood & Sons, Beauties of the New-England primer p.4-21

[22] Samuel Wood & Sons, Beauties of the New-England primer p.22-30

[23]Westminster Assembly. The New-England primer improved: for the more easy attaining the true reading of English, to which is added, the Assembly of Divines, and Mr. Cotton’s catechism. Boston: Printed for and sold by A. Ellison, in Seven-Star Lane, 1773. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/22023945/ ,p.29-31

[24]Mydland, Leidulf. “The Legacy of One-Room Schoolhouses: A Comparative Study of the AME…” European journal of American studies. European Association for American Studies, February 24, 2011. https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/9205.

[25]Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001.p.255

[26]Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory p.257

[27]Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory p.287

[28] Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory p.283

[29]Swinton, William. Swinton’s Condensed United States: A Condensed School History of the United States: Constructed for Definite Results in Recitation and Containing a New Method of Topical Reviews. New York, Chicago: Ivinson, Blakeman & Co., 1871, p. 235

[30] Swinton, Swinton’s Condensed United States: A Condensed School History of the United States p. 236

[31] Swinton, Swinton’s Condensed United States: A Condensed School History of the United States p. 288-291

[32] Swinton, Swinton’s Condensed United States: A Condensed School History of the United States p. 237

[33] Wolinetz, When Slavery Wasn’t a Dirty Word in NJ

[34] New Jersey. Laws, Statutes, Etc. An act for the gradual abolition of slavery … Passed at Trenton . Burlington, S. C. Ustick, printer 1804. Burlington, 1804. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.0990100b/.

[35] New Jersey, An act for the gradual abolition of slavery.

[36] Gigantino II, James J. “The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865-1941.” New Jersey Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 35–55. 2020, Academic Search Premier doi:10.14713/njs.v6i1.188. Accessed 9/28/22.

[37] Gigantino II, James J. “The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865-1941.” p.36

[38] Gigantino II, James J. “The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865-1941.” p.37

[39] Stockton, Frank R. “Stories of New Jersey.” Amazon. OUTLOOK VERLAG, 2020. https://www.amazon.com/Stories-New-Jersey-Frank-Stockton/dp/0813503698.

[40] Stockton, Frank R. Stories of New Jersey. American book company, 1896. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/01007755/.p. 6

[41] Stockton, Stories of New Jersey, p.84-85

[42] Stockton, Frank R. “Stories of New Jersey.” p. 86

[43] Stockton, Frank R. “Stories of New Jersey.” p. 86-89

[44] Stockton, Frank R. “Stories of New Jersey.” p. 92

[45] Stockton, Frank R. “Stories of New Jersey.” p. 92

[46] Stockton, Frank R. “Stories of New Jersey.” p. 92

[47] Gigantino II, James J.“‘’The Whole North Is Not Abolitionist’’.” Journal of the Early Republic 34 (3): 411–37. 2014, Academic Search Premier doi:10.1353/jer.2014.0040. Accessed 9/28/22, P.38

[48]Thomson, Jay Earle. An elementary history of New Jersey. [New York, Philadelphia etc. Hinds, Hayden & Eldredge, inc, 1924] Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/24011186/. P.iv

[49] Thomson, An elementary history of New Jersey P.v

[50] Thomson, An elementary history of New Jersey P.ix

[51] Thomson, An elementary history of New Jersey P.150

[52]Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018. p.2

[53] Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition p.65

[54] Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition p.67

[55] Thomson, An elementary history of New Jersey P.iv

[56] Gigantino II, James J. “The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865-1941.” p.36

[57] Wilson, American History p.iv

[58]Wilson, Howard E, and Wallice E Lamb. American History. Schoharie, NY: American Book Company, 1947. p.27-29

[59] Wilson, American History p. 209-236

[60] Wilson, American History p.249-257

[61] Wilson, American History p. 280-286

[62] Vikos, George and Greenstein, Andrew. Conversation at Marina cafe, Staten Island NY, November 14th, 2022

[63] Vikos, Conversation at Marina cafe, Staten Island NY, November 14th, 2022

[64]Gordon, Irving L. Review Text in American History. New York, NY: AMSCO School Publications, 1980 p.21-25

[65] Gordon, Review Text in American History p.22

[66] Gordon, Review Text in American History p.157

[67] Gordon, Review Text in American History p.184

[68] Gordon, Review Text in American History p.186

[69] Vikos, Conversation at Marina cafe, Staten Island NY, November 14th, 2022

[70] Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 13th ed., 15th ed, 16th ed, Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2006, 2013, 2016.

[71]Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 13th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2006. p.356

[72] Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 13th ed. p.357-358

[73]Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 15th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2013 p.341-344

[74] Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 16th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2016. p.352

[75] Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 16th ed. p.355-359

[76] Gigantino II,“‘’The Whole North Is Not Abolitionist’’, P.46

[77] Samuel Wood & Sons, Beauties of the New-England primer

[78]Blight,Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory .P.255

[79] Swinton, Swinton’s Condensed United States: A Condensed School History of the United States p. 236-291

[80] Stockton, Stories of New Jersey, p.84-85

[81] Thomson, An elementary history of New Jersey P.4-157

[82] Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition p.2-47

[83] Wilson, American History p.27-29, 209-257

[84] Vikos, George. Conversation at Marina cafe, Staten Island NY, November 14th, 2022

[85] Gordon, Review Text in American History p.21-25, 157-186

[86] Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 13th ed. p.356-462

[87] Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 15th ed. p.341-442

[88] Bailey, Thomas, David Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen. The American Pageant. 16th ed. p.343-435

[89] Jay, Lyerly. Understanding and Teaching American Slavery p.9

[90] Gigantino II, James J. “The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865-1941.” p.36