Herman P. Levine: A Brooklyn School Teacher in the Mexican Revolution

Dan La Botz

This article was adapted from the author’s book, This Riding with the Revolution: The American Left in the Mexican Revolution: 1900-1925 (Leiden: Brill, 2024).

Herman Levine, a Brooklyn public school teacher, was a Socialist, an anti-war activist, and on June 5, 1917, his personal and political convictions led him to refuse to register for the draft—and he said so publicly. The result was a series of conflicts with the draft board, the school board, and the courts that propelled him to seek refuge in Mexico, then in the midst of revolution. He would spend several years there, organizing the Industrial Workers of the World until he was deported back to the United States.

Born in 1893, Levine had grown up in in Brooklyn. He attended Public School 84 in Brooklyn, graduated with honors, and then went on to Brooklyn Boys’ High School and later took courses at City College of New York where he was an outstanding student. In 1913 he won the college’s first annual oration contest with a speech titled: “War—What For?”1 Like many Jewish immigrant children, Levine aspired to become a professional, in his case an educator.1 In 1914 Levine became a schoolteacher, taking a job at Public School 160 at Rivington and Suffolk streets on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and became active in his profession. “He originated a series of departmental conferences in which he wrote and lectured extensively,” wrote a newspaper reporter. “This system was made the subject of a special borough teachers’ conference in September 1916.”2 While

teaching, the intellectually ambitious Levine also took courses in history and government at Columbia University.

1 “Draft Opponent,” The Call, 13 June 1917; “Draft Slackers,” The Call 7 June 1916.

2 ‘Draft Opponent May Be Jailed’, The Call, 13 June 1917.

In addition to his teaching and studies, Levine was active in the Socialist Party and a member of the Addison Socialist Club in Brooklyn. One of the Socialist Party’s principal activities was anti-war

work, and Levine was also an anti-war activist. In early April of 1917 he participated in a lobbying effort as part of a peace delegation to the U.S. Congress in Washington, D.C. He also served as a

delegate from the Addison Socialist Club to the First American Conference for Democracy and Terms of Peace, which had been organized by the newly formed People’s Council.

Twenty-three years old when the U.S. began conscription on 5 June 1917, Levine was required to register. “He surrendered himself to authorities after registration day, declaring that he was opposed to war and therefore was compelled by his principle to refuse to register, as to do so would mean acquiescence in the war,” reported the Socialist newspaper The Call.3 Levine reported voluntarily on 6 June to United States Marshal James M. Power, announcing that he had not registered and did not intend to. Not having $1,000 bail, he spent the night in the Raymond Street jail. On 7 June he appeared for arraignment in federal court in Brooklyn with his attorney Winter Russell.4 In short order Levine was tried and found guilty of violating the conscription law.

On 18 June Levine appeared in court again, this time for sentencing. United States Judge Chatfield offered him one more chance to register. His parents and sisters begged him to take it. “Levine replied that he believed the war to be unjust, and that as his principles forbade him to fight, he would not register.”5

3 “Draft Opponen,” The Call,’ 13 June 1917.

4 “Kramer Trial,” The Call,8 June 1917.

5 “Limit of Law,”The Call, 14 June 1917; “Get’s Law’s Limit,” The New York Times,14 June 1917.

6 ‘Levine Dismissed,” The Call, 13 July 1917; “Board Dismisses Levine,” The New York Times,12 July 1917.

The Judge then sentenced Levine to serve 11 months and 29 days—the maximum penalty less one day. The judge stipulated that the sentence had to be served in jail with no time off for good behavior.

Before leaving the courtroom, Levine was involuntarily registered for the draft by the

authorities.

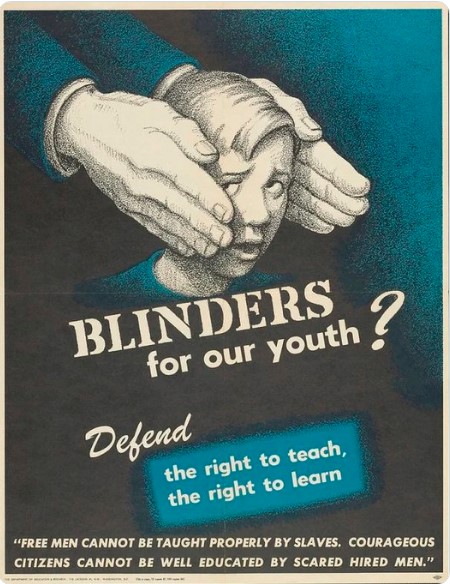

Apparently, a prison term was not enough punishment, for Levine was also fired from his job. The state commissioner of education deprived Levine of his license to teach, and the school board at a meeting on 11 July 1917 dismissed him from his teaching position at Public School 160.6 The state and the school board made it impossible for Levine to practice his profession in his native state, and no doubt this became another factor in driving him into exile.7

While in jail, Levine was duly notified that he would still have to appear for his mandatory physical examination. Standing on his principles, he wrote from jail to The Call, rather sententiously, “I shall…not raise any technicality, but offer myself as a sacrifice, if need be, to the greedy, exploiting and devastating system of capitalism.”8 As Levine’s statement makes clear, he was a conscientious objector to the war because he was a socialist opposed to capitalist wars.

In Minneapolis, Minnesota on 21 September 1919 the board of education dismissed D.J. Amoss from his teaching job at Central high school because of his alleged membership in the Industrial Workers of the World.

7 “Minneapolis Teacher,” The Call, 22 September 1917, p. 9.

8 “Levine Refuses Physical Test,”, The Call, 9 August 1917.

He asserted, “My life will affirm what my mind and heart dictate. I have refused to do their bidding by refusing. Such actions were not uncommon at the time.to register. I will refuse to do their bidding in the future.”9 Levine’s statements published in The Call, thus also served, as he surely realized, as anti-draft and anti-war propaganda. His own intransigence might serve an inspiration to other young men to resist.

Levine also wrote a letter from jail to a friend who then passed it on to be published in The Call:

My fate is by no means sad. What can be higher than to oppose that barbaric and inhuman process of killing our fellow men whom we have never seen and against whom we bear no hatred. I cannot be really sad, and if gloomy moments do appear, they are hurried off by the gleam of the coming day.10

“The coming day,” as his friend and the readers of The Call would have understood, was an allusion to the coming socialist revolution. Levine advised his correspondent, apparently, another socialist

conscientious objector, to stick to his principles.

9 “Levine Dismissed by School Board,” The Call, 40; “Teacher Who Resisted Draft Content in Jail,” The Call, 3 September 1917.

10 ‘Teacher Who’ 3 September 1917.

Having been registered against his will in prison, when Levine finished his prison sentence, he was still subject to the draft, and, if he refused, to imprisonment. Evidently preferring his freedom, he must have left for Mexico immediately upon release in June 1918. Levine reached

Mexico City shortly thereafter, and adopted two aliases and identities: Mischa Poltiolevsky, claiming to be a Russian immigrant, and Martin Paley, an American schoolteacher. Levine’s experience in jail and prison must have hardened his radical convictions, for when he left and fled to

Mexico, he continued his political activity, though now as a leftist labour organiser rather than as an anti-war activist.

A Brooklyn school teacher in Tampico

Levine’s decision to go to Mexico was not unique. Americans didn’t go to Canada because it was part of the British Empire which was already at war. Mexico credate no barriers to American war resisters who wanted to enter the country, and what began as a trickle became a steady stream, and

soon, some would claim, a flood. The New York Times reported in June of 1920—a year and a half after the end of the war—that an estimated 10,000 draft evaders still remained in Mexico.11 Senator Albert Bacon Fall told the Associated Press that an estimated thirty thousand Americans had crossed into Mexico to evade the draft law.12 American politicians and the press called them “slackers,” a derogatory term that the war resisters adopted as a badge of honor.

Many American war resisters went to Mexico City, but Levine went to Tampico in the state of Tamaulipas, a city that was then a center of the relatively new oil industry dominated by British and American companies. He eventually found work as a clerk there set about re-organizing the local

chapter of the Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the Wobblies.

Tampico, the principal port for the Mexican oil industry, had developed rapidly beginning with the outbreak of the war in Europe in 1914. With the expansion of industry there was also a rapid growth in the number of oil workers, stevedores and seamen. These workers, often led by Spanish anarchists or sometimes American Wobblies, formed unions which grew rapidly in size, strength, and militancy.

11 ‘Ask Mexico to Send Draft Dodgers Back,” The New York Times, 7 June 1920, p. 9.

12 Linn A.E. Gale, “They Were Willing,” Gale’s Magazine, March 1920, p. 1. 3

Labor unionism in Tampico had begun during the first years of the twentieth century when workers had established a variety of unions, such as the Moralizing Union of Carpenters (Unión Moralizadora

de Carpinteros). By 1915, the major anarcho-syndicalist labor federation, the House of the World Worker, had reached Tampico, and began organizing both trades and industrial workers. The practice of striking to improve wages and working conditions became widespread and frequent among workers in Tampico.13

The Industrial Workers of the World already had a foothold in Tampico before Levine arrived. While it remains unclear if the IWW had any specific strategic plan for Tampico, in general the IWW organized unions of workers in a particular industry with the goal of affiliating them eventually into a national and then a worldwide industrial union, the One Big Union, as they sometimes called it.14

13 Gruber, Adelson, Steven Lief 1982, “Historia Social de Ios Obreros Industriales de Tampico, 1906 1919,” (Doctoral dissertation, 1982, Colegio de México), pp. 424–70.

14 Cole, Peter, David Stuthers, and Kenyon Zimmer 2017, Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW.

In the United States, the IWWs strategy led it to organize oil workers, copper miners, lumberjacks in the spruce forests, and agricultural workers in the wheat fields: all strategic wartime industries (spruce wood was used to build airplanes). Following capital and heavy industry over the border to the south, Wobblies found themselves working in Mexican mines and oil fields, as well as on

Mexican docks and on ships of various nations. There they would employ the same strategy of industrial unionism and direct action.

One group of the Industrial Workers of the World arrived in Tampico in force in 1916 when the C.A. Canfield arrived in port. The crew of the Canfield belonged to the IWWs Marine Transport Workers (IWW MTW), and many were Spanish speaking. They recruited Mexican seamen to their union, which probably also gained a foothold among the stevedores. Pedro Coria, a Mexican IWW organizer from Arizona arrived in Tampico in January 1917 and organized Local #100 of IWW-MTW.15 Workers in Tampico had many grievances, (London: Pluto Press, 2017), pp. 124 but one of their major complaints was that they were paid in varying worthless currencies, so they demanded pay in gold or silver. In 1917 there was a series of strikes that began over this issue, culminating in a

great general strike in the Tampico area involving petroleum workers and stevedores from both the House of the World Worker and the IWW.16 The US Embassy sent a note to the Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs in October of 1917 on ‘The Tampico Situation’, which gives an impression of the

US government’s concerns. The note reads:

Reports from Tampico indicate that place is quiet but that labor leaders are agitating for a general

strike to which the Germans and Industrial Workers of the World are disposed to lend support. It is

reported that the National Socialist Congress to which delegates from the United States and Cuba have been invited is now in session. A great many of the delegates are said to be anarchists, and the situation seems charged with danger.17

On 8 January 1919, Excelsior, a Mexico City newspaper, repeated a story that had apparently originated in New York that there were “secret soviets” in Tampico, organized by the IWW.18

15 Norman Caulfield, “Wobblies and Mexican Workers in Mining and Petroleum, 1905-1924,”

International Review of Social History, April 1995, Vol. 40, No. pp. 51-751995), p. 57.

15 Cole et all, Wobblies, pp. 124–39. 16 Cole et all, Wobblies, pp. 124–39.

17 US Embassy to Mexican Secretary of Foreign Relations, unsigned, ‘Memorandum: The

Tampico Situation’, 13 October 1917, Expediente 18-1-146, SRE.

18 Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Los Bolshevikis: Historia narrativa de los orígenes del communism en Mexico: 1919

By the time Levine arrived in Tampico in 1919 or 1920, the IWW was an established organization among industrial workers with a legendary militancy. Levine joined in the work of the IWW as editor of the group’s newspaper. In 1920, US intelligence agents reported that Mischa Poltiolevsky—they apparently believed this was Levine’s real name—”is working in Tampico under the name of M. Paley. He is a very active agent/”19 They were correct.

Levine had become one of the most dynamic leaders of the Tampico IWW organizing among stevedores and oil industry workers. The former socialist Levine had undergone a conversion experience: he had given up his membership in the Socialist Party and had joined the IWW. During the period between 1917 and 1919, he rethought his political ideals, rejecting his belief in socialism and espousing instead revolutionary syndicalism. In a letter to the Industrial Workers of the World headquarters in Chicago, he explained his personal situation and his political views:

I have never learned a trade, nor am I a manual worker, and this I regret, for I recognize that the workers on the job must prepare themselves to run industry, and the workers on the job must determine radical tactics during the struggle to attain their aim, because they alone are surrounded by that environment from which real radical measures surge. I am opposed to political action. An

industrial administration must be prepared for industrially. Political action wastes energy that could be used in the class struggle—on the job. I intend to learn a trade as soon as possible, so that my views may arise in the proper environment. Until then, I shall suggest nothing— but shall affirm that radicals on the job, in the factory, on the farm, in the mine—theirs is the final voice.

1925 (Mexico: Joaquin Mortiz, 1986), p. 32.

19 Memo of 26 May 1920 from the military attaché of the American Embassy to the Director

of Military Intelligence, G.S., Washington, D.C. on the subject of Bolshivist [sic] propaganda,

Record Group 165, Box 2290, USMID, USNA.

Levine concluded his letter, “I was a member of the Socialist party, Local Kings [County], N.Y., but sent in my resignation last May [1919].” In a hand-written postscript he added, “As soon as I become a worker on the job, I intend to join the IWW. But for the present as an office worker, I cannot do so.”20

Why did Levine leave the Socialist Party? Perhaps because so many prominent figures in the party had supported the war and even gone to work for the Wilson administration. Or maybe Levine had fallen under the influence of American or Mexican Wobblies who had convinced him of their

revolutionary syndicalist principles and strategy. Or perhaps his own experience as a slacker had simply driven him to the left, and, at the time, the far left was the IWW.

20 Letter (unsigned) by Levine to Whitehead, November (date scratched out), 1919, Record Group 165, Box 2290, USMID, USNA. 21 A number of copies of El Obrero Industrial can be found in Record Group 165, USMID, US

In any case, though he did not have an industrial job—or perhaps precisely because he did not have such a job—Levine, using the name M. Paley, became the editor of the Tampico IWW newspaper, El Obrero Industrial (The Industrial Worker). The newspaper was just one or two tabloid size sheets of paper folded into four or at most eight pages, written in Spanish it was aimed at the Tampico oil workers and stevedores. Its articles advocated direct action and industrial unionism and called for the use of the general strike to create a workers’ government.21 Levine’s newspaper and his

organizing activities became a serious concern to the US Military Intelligence Division (USMID). The USMID officer in Laredo, Texas wrote to his superiors in July 1920:

The [US] Government is receiving copies of “The Industrial Worker” [El Obrero Industrial] paper being printed in Tampico, which in its editorials is spreading the doctrine of Lenine and Trotzky. The paper says the strikers will not cease until they have accomplished their purpose. Reports also state that at their meetings the strikers have red flags and that the cry ‘Vive la Russia’ [sic] can be heard. The oil companies told the laborers that the pay will not be increased one cent, as they claim

they are paying the best salary in the country.22

National Archives. The newspaper reported on local activities in Tampico, but its main political ideas were identical to those of the IWW of the United States: direct action, industrial unionism the general strike.

At the time many IWWs were supporters of the Russian Revolution and the Soviet government, and some were attracted to the Bolsheviks, who were in the process of organizing the Communist International. As editor of El Obrero Industrial Levine, like other Wobblies, followed the Russian

Revolution with sympathy and offered it his support from afar. Later he would join in the foundation of the Mexican Communist Party (PCM).

The writer B. Traven, whose real name was Ret Marut and who was a German revolutionary refugee of the post-war conflicts in that country, lived in Tampico in the early 1920s. Traven spent some time

with members of the Industrial Workers of the World and left a picture of the American radicals in his novels Die Baumwollpflucker (The Cottonpicker) and Der Wobbly (The Wobbly). In his fictional account of a strike Traven gives us some idea of Levine’s Tampico:

in this country [they] do not suffer from a clumsy, bureaucratic apparatus. The union secretaries do not regard themselves as civil servants. They are all young and roaring revolutionaries. The trade unions here have only been founded during the last ten years, and they have started in the most modern direction. They absorbed the experience of the Russian Revolution, and they embody the

explosive power of a young radical force and the elasticity of an organization which is still searching

for its form and changes it tactics daily.23

22 Report from Intelligence Officer, Laredo, Texas, to department Intelligence Officer, Fort

Sam Houston, Texas, 23 July 1920, Record Groups 165, in Box 2291, USMID, USNA.

23 Heidi Zogbaum, B. Traven: A Vision of Mexico (Wilmington, DE: SR Books,

Traven’s stories and novels caught the spirit of Tampico’s Wobblies and other radical unionists.

The employers took the matter of what they saw as the foreign-inspired labor unions in Tampico quite seriously.

R.D. Hutchinson, of the British ‘El Águila’ Oil Company told the Bulletin of the National

Chambers of Industry that the Tampico general strike of 1920 represented a “giant step toward the dictatorship of the proletariat,”

He went on: Mexican workers have unionized with the goal of imposing themselves on capital in Tampico and they have done it at the insistence of two different kinds of agitators: some foreigners, who, preaching Bolshevik ideas, have done a profound job, a deep job among the proletarians of the oil zones; and the others, Mexican politicians, who pursuing, if not identical goals, disrupt the peace by attacking the established interests at this crucial moment.24

As both Traven’s novel and this company manager’s remarks suggest, Levine, Coria and other slackers together with the Mexican workers had constructed a powerful, radical industrial union movement in Tampico that threatened the existing order.

Scholarly Resources Inc., 1992), p. 14, citing B. Traven, , Die Baumwollpflucker. (Hamburg. 1962),

p. 72. Wobbly movement.

The British government was also alarmed at the growth of the IWW in Tampico and other cities. The British Ambassador, H.A.C. Cummins reported to Lord Curzon at the Foreign Office in London in April of 1921, “The I.W.W. organization obtained some influence here during the war, an influence which has not lessened, and it is known that the confederated labor unions [CROM] are being directed by these dangerous extremists, and that they are laying plans with a view to establishing a Soviet administration in Mexico.”25 As Cummins’s communication indicates, in Tampico both

the IWW and the more moderate state sponsored CROM unions carried out militant campaigns against the employers.

While both foreign employers and foreign consuls sometimes exaggerated the threat from the IWW, their exaggerations were based on the very real, and quite formidable Wobbly Movement.

24 “Las Últimas Huelgas Según Seis Industriales Prominentes,” Boletín de la Confederación de Cámaras

The fight within the Mexican IWW

There are always fights between people in business and politics and the 1910s and 20s were a period of particularly ferocious struggles everywhere. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson fought the Socialist Party and the IWW, severely weakening the former and virtually destroying the latter. The Republicans fought the Democrats and defeated them leading to the reactionary and corrupt President Warren G. Harding. In Russia, Joseph Stalin fought and defeated Leon Trotsky. In America Socialists fought Communists and the AFL fought the IWW. So it is not surprising that here was also a fight in the Mexican IWW.

In Mexico, it became a personal fight between slackers Herman Levine and Linn A.E. Gale over the question of who represented the real IWW in Mexico. Gale was a small-town journalist, a former low level, local politician from New York, facing criminal prosecution for his debts and also fearing he might be drafted fled to Mexico with his wife Magdalena, a secretary who worked to support him. He published Gale’s Magazine which combined socialism and spiritual and promoted himself as the leading American leftwing intellectual and activist in Mexico, mailing his magazine to influential American radicals.

Industriales, (August 1920) , pp. 10 25 Bourne n.d., p. 307.

While Levine worked in Tampico organizing petroleum workers into the IWW, Gale, with the political backing of Mexican President Venustiano Carranza’s Minister of the Interior, Manuel Aguirre Berlanga published article s supporting Carranza’s notoriously corrupt and avaricious government, claiming it was progressive or even potentially socialism. At the same time, Gale claimed to be the leader of the Mexican IWW, and though he didn’t do much organizing, he gave out

IWW membership cards and photographs of the American Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs.

The situation was complicated by the fact that Gale also claimed to be the head of the Communist Party of Mexico (PCdeM), made up of the same clique that formed his IWW, while Levine sympathized with the rival Mexican Communist Party (PCM) that had been established by American slacker Charles Francis Phillips, Indian Manabendra Nath Roy, and Russian Bolshevik (Communist) Mikhail Borodin. All of this was taking place at a brief moment when revolutionary syndicalists around the world were briefly attracted to the Communist movement, just as they were in Mexico.

We know Levine’s opinion of Gale and his IWW group from a long letter (eight single-spaced pages) in which Levine wrote to “Fellow Worker Whitehead,” that is, Thomas Whitehead, the secretary-treasurer of the IWW in the United States. Whether or not a copy ever reached Whitehead is unclear, because the letter was intercepted by USMID. Levine portrayed Gale as the

antithesis of a genuine labor organizer. The letter gives us a great deal of insight into

Levine’s political principles and his notion of the proper role as an American revolutionary and labor organizer in Mexico and it is worth reviewing in some detail.26

26 The following several citations come from this letter. Letter (unsigned) to Whitehead from Levine, date November (date scratched out) 1919. Box 2290, Record Group 165, US National Archives.

Levine wrote, ‘He [Gale] is a businessman seeking political preferment and social position’, while Gale’s Magazine is ‘not a radical nor socialist organ’. He went on:

The name characterizes it admirably. It is Gale’s magazine—to boost Gale, first, last and all the time. No sincere radical ever did nor ever will launch a magazine with his name in the title. Levine claimed that Gale had had little contact with Mexican workers, but that those few Gale had met had been disgusted by him.27

Levine was particularly critical of Gale’s praise of Carranza and Berlanga.

“The Mexican government is a government of the government, by the government and

for the government,” wrote Levine. “They are not frank in their statements—but they are brutally frank in their acts; force, brute force being the rule and Berlanga is the official in charge of such proceedings”.

27 Letter (unsigned) to Whitehead from Levine, date November (scratched out) 1919. Box 2290,

Record Group 165, US National Archives. The following several citations come from this letter.

Levine pointed out to Whitehead that it was Berlanga who had quashed the teachers’ strike of 1919.

In general, Levine was critical of Gale’s notion that the Mexican government was a radical government moving toward socialism. What had the peasants and workers gained? asked Levine. “The worker’s reward? The right to have the military forces used against him when he goes on strike, printing presses seized, union halls closed.” Levine gave the examples of the suppression of the Mexico City teachers strike in May and of the Tampico oil workers strike in November of 1919.

“What is the essence of the Mexican Government?” asked Levine rhetorically. “It is an incipient capitalist state.” Carranza, Levine argued, had ‘tried to establish industry on a firm capitalist basis’, inviting the Chambers of Commerce of Dallas, Chicago and other US cities to come to Mexico to help:

Carranza invited them to invest capital in Mexico, but denied them any special privilege. He wants

Mexico to develop on a capitalist basis, without intervention of foreign capitalist governments. “Mexico for the Mexican Capitalists, for the Mexican Government” is his slogan.

Most modern historians would agree with Levine’s assessment of the Carranza regime. Levine argued that Gale’s call for support of Mexico against foreign intervention missed the point that the Mexican government actually supported foreign economic investment and protected foreign investors.

Tampico oil is in the hands of foreign exploiters. But when workers go on strike, the union halls are

closed down, printing presses seized despite specific constitutional provisions to the contrary, right of assembly denied—by whom? Not by foreigners, but by the military officials of that very government which we are asked to defend. Levine lumped Gale together with

Gompers as foreigners meddling in Mexican workers’ affairs:

Mexican radical policy will be determined by Mexicans. The Mexican working class is fighting its

fight where it ought to be fought—on the job. It [the Mexican working class] is not revolutionary—but it becomes aroused over the right to organize—as is proved by the Orizaba [textile] strike now before the public eye. Mexican Labor is too conservative, its leaders and organizations being bound up with the American Federation of Labor. But there are radical elements, and it is to them that we must look for action.

Interestingly, while he and other American slackers participated in the Mexican labor movement, Levine clearly believed that Mexican workers should ultimately determine its policies. Levine concluded his critique by arguing that:

Radicals should fight intervention, not by praising and supporting the Mexican Capitalist Government—but by denouncing the war as capitalist in its origin, by refusing to fight for the American Capitalist and his Mexican counterpart, and by demonstrating that the only sane

solution for Intervention is Workingclass [sic] Revolution.

American radicals should fight against American Capitalism; Mexican Comrades should fight their

own exploiters. The class struggle— cannot—will not— be sidetracked.

The letter ended: “cooperation with [Gale] by the IWW is dangerous to the Wobbly movement.” Levine clearly believed that genuine labor organizers would work not with Mexico’s capitalist government, but with the “radical elements” among the industrial workers in the organization of the class struggle. Levine, as this letter makes clear, held Gale in utter contempt.28

28 Letter (unsigned) to Whitehead from Levine, date November (date scratched out) 1919. Box

2290, Record Group 165, US National Archives.

The fight for the backing of the American IWW

The battle between the American slackers for control of the Mexican Industrial Workers of the World was fought both in Mexico and in the pages of the IWW magazine and newspapers in the United

States. Both slacker groups in Mexico wanted the endorsement of the Chicago headquarters of the IWW, and each wrote long articles arguing its point of view and attacking the opposition. The imprimatur of the Chicago office of the IWW was just as important for the slacker unionists as the

endorsement of the Moscow headquarters of the Communist International was for the slacker Communists.

As usual, Linn Gale struck the first blow with an article titled ‘The War Against Gompersism in Mexico’ published in November 1919 in The One Big Union Monthly, the magazine of the IWW

executive committee in the United States. He recounted the first national congress of the Mexican Socialist Party and attacked M.N. Roy for voting to admit Gompers. He also attempted to discredit.

The Indian revolutionary M.N. Roy. Gale wrote that the ‘Hindu’ (M.N. Roy) is “said by some to be a

spy for the American government. As to the truth of this I do not know.” He claimed that during the congress Roy had been “working hand-in-hand with [Luis N.] Morones,” the corrupt leader of the CROM. Gale explained that “Roy voted in favor of seating Morones, casting the deciding vote!!!” Consequently, Gale explained, he and others had withdrawn from the Socialist Party and formed Communist Party of Mexico, a tiny group headed by Gale, which was “in favor of Industrial Unionism.”

The following several citations come from this letter.

The editor of The One Big Union Monthly observed that,

“Not knowing the condition in Mexico, we publish the above with some mental reservation, insofar as we believe that the I.W.W. men of Mexico may take a different view of cooperation with the new Communist party.”29 In the same issue there appeared an excerpt from Gale’s Communist Party of Mexico manifesto, obviously sent to the paper by Gale, endorsing the IWW, denouncing the AFL,

calling for the use of strikes, boycotts and sabotage, and looking forward to the eventual establishment of the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat.” The manifesto also called for a “Constant and intelligent co-operation between the Communist Party and the industrial unions of Mexico and the Communist Parties and industrial unions of other countries.”.30

29 Linn A.E. Gale, “The War Against Gompersism in Mexico’, The One

Big Union Monthly, November 1919, pp. 23–5.

30 “I.W.W. in Mexico,” The One Big Union Monthly, November 1919, p. 50.

The other slacker faction was not long in responding in the American Wobbly press. Irwin Granich [Mike Gold] wrote a long article, “Sowing Seeds of One Big Union in Mexico,” in which he described political, economic, and social conditions, and rebutted Gale’s attack. Granich gave his

own report on the first national congress of the Mexican Socialist Party, and his own interpretation of events. First, he argued that the Socialist Party congress really functioned as a kind of IWW convention. As he put it:

The Socialist party, dominated by I.W.W. elements, had called the congress because there was no union able to call it. It was called for the purpose of bringing to the workers the message of One Big Union and to help them create a national body based on industrial lines.

The Mexican Socialist Party congress, said Granich, succeeded in doing so despite the sabotage of Luis Morones and Linn Gale. He described Gale as “an American adventurer and labor provocateur

who has a shady past and has just organized a so-called Communist party of six or seven members for some sinister ends.” Gale “is really a nonentity, dangerous only because he is trying to bleed the movement for money, and because he is of the type that will ultimately sell out and turn spy—if he

has not already achieved this profitable end, as the Soviet Bureau in New York believes.” Granich asserted that despite Morones and Gale, the congress had been a success and the delegates had launched two new magazines, El Soviet in Mexico City and El Obrero Industrial in Veracruz.31

31 Irwin Granich, Irwin [pseud. of Michael Gold], “Sowing the Seeds of One Big Union in Mexico,” The One Big Union Monthly January 1920 , pp. 36–7.

In the March 1920 issue of The One Big Union Monthly, the editor felt obliged to explain why he was continuing to print letters from the rival slacker factions in Mexico, and his explanation bears citation because it shows the American IWW’s interest in establishing continental industrial

unionism. “First,” wrote the editor,” it is just as important for us to be familiar with conditions down in Mexico as it is for us to know conditions in Canada. The question of direct cooperation between the One Big Union of Canada, of United States and of Mexico is bound to come up in the near

future, and for that reason it is necessary that we should be somewhat conversant with men and condition[s] in Mexico as well as in Canada.”

“Second,” wrote the OBU editor, “we want our members to know the state of affairs down in Mexico City when they get down there, so they do not act blindly.” Finally, said the editor, the IWW rejected

political parties, whether Socialist or Communist. “We enjoy to see the politicians destroy one another before an audience of wage workers,” because “it fills the workers with disgust for the political game and makes them turn to industrial organization.” So he let the debate in the pages of his magazine continue.32 The editor asked that future articles respond to a number of specific questions, namely a history and survey of the Mexican labor movement, a discussion of the experiments in the Yucatan, a discussion of the roles of Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, and a

survey of Mexican industry with statistics.

32 John A. Jutt, “The Mexican Administration of the I.W.W,”

José Refugio Rodríguez, Secretary of Gale’s IWW organization, took up the offer and wrote an article on “The Working Class Movement in Mexico” which avoided the recriminations of the earlier articles and described general conditions of Mexican labor. Rodriguez’s article characterized the

various leaders and tendencies in the Mexican Revolution. He rejected support for Álvaro Obregón, who was “seeking the support of the American and Mexican financial interests,” and also repudiated

Carranza who was “at best only a Liberal.” Rodríguez also characterized Villa and Zapata. He wrote (wrongly and falsely) that the former “is no more and no less than a despicable murderer who once served in the American Army and there learned completely the science of killing his fellow human beings.” He expressed admiration for Zapata as an “honest man,” but noted that “the tales published in foreign periodicals about the wonders of ‘Zapataland’ make us laugh and also make us shed bitter tears”:

His “Zapataland” only existed over a few hectares of land in the days of its greatest success. It was very crude, undeveloped, unorganized, and could not therefore, last long. In the great land over which Lenin is the guiding figure and where Industrial democracy has come to remain forever, there is much of science, order, skill, wisdom and shrewdness, to match that of the capitalist empires without. But there was none of this in “Zapataland”—only honest intentions, high ideals, bad

organizations, big blunders and inevitable failure.33

Gale’s Magazine, February 1920, p. 44.

What is striking in Rodríguez’s essay is the nearly complete rejection of all of the Mexican revolutionary factions, including the plebeian movements of Zapata and Villa, and his absolute confidence in Lenin and the Russian model. Gale and his comrades, it seemed, having rejected the Mexican revolution entirely, intended to implant the models of the Chicago-based IWW and the

Moscow-centered Communist International.

Levine leads the IWW into the United Front

Whatever appeared in the papers in Chicago, the fight to control the Mexican IWW would be settled in Mexico and Mexican workers would play a central role. Levine had found two allies in his struggle against Gale. Both Charles King and Pedro Coria had been active; in the Industrial Workers of the World in the United States, as well as in Mexico. A USMID report, probably written by José Allen, who was simultaneously head of the Mexican Communist Party and a US spy, described

Levine’s new supporters. The description of King was brief:

King claims to be an American Communist. He has been in Mexico approximately eighteen months. He is five feet eight inches tall; weight about one hundred and sixty pounds; dark hair; dark eyes; swarthy complexion. He is very sarcastic and cynical. He appears to be very well educated; he speaks Spanish and English equally well. Trade unknown.

33 José Refugio Rodríguez, “The Working Class Movement in Mexico,” The One Big Union Monthly, 1920 II, no. 6, 26-27.

The spy’s account of Coria went into more detail, painting a picture of a sophisticated political activist. “Corea [sic] is a Mexican of the railroad man type; age about forty; about five feet eight inches tall; weight about one hundred and eighty pounds; thick, black hair; black eyes; slightly florid complexion,”, wrote Allen.

“He has travelled very widely in the United States and South America; he speaks English very well. He is said to speak Portuguese fluently. For many years he has been a political leader. He is said to have been imprisoned in South America. He is not a very well educated man, but an active mind and great personality make him a leader.”34

34 ‘Who’s Who Material – Mexican Radical Elements’, 15 October 1920. RG 165, Box 2290.

Coria told his own story in an autobiography written in the 1960s. Raised in a military orphanage, Coria eventually became a foundry worker and after working in several Mexican cities travelled to the United States. While living in Chicago, Coria learned to speak English fluently and also became acquainted with the American labor movement. He apparently attended an early convention of the Industrial Workers of the World and became a Wobbly. As a Wobbly organizer in various parts of the

West, Coria had participated in numerous organizing campaigns, strikes, and protest demonstrations.

At various times he was beaten, jailed, and had his life was threatened. As a working-class pacifist in the United States, he opposed both the violence of the revolution in Mexico and United States involvement in World War I. When the Wilson administration suppressed the IWW, Coria fled to Tampico, no doubt because he knew there was an active IWW group there.35

35 Coria, Pedro, “Adventures of an Indian Mestizo,” Industrial Worker (Chicago), January, February,

March, April, and May, 1971. Thanks to Robert J. Halstead for calling this series to my attention and providing a photocopy.

As soon as he arrived in Tampico, Coria made contact with the IWW and joined other Wobblies in organizing Petroleum Workers Industrial Union 230 and Marine Transport Workers union 510. He quickly became one of the most prominent IWW leaders in Tampico and was sent by the local IWW as delegate to the important labor convention in Saltillo, Coahuila held on 1 May 1918, the meeting that produced the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM). It must have

been not long after returning from Saltillo that Coria met Herman P. Levine.

Coria’s experience made him a highly valuable IWW organizer. His knowledge of English and Spanish, his familiarity with the labor union and political movements in both countries, and his

courage and dedication made him particularly useful in the attempt to organize the IWW in Mexico. So, it was natural that in Tampico, Coria became one of the closest allies of Levine.

Levine—now backed up by Coria and King—proposed at the 17 October 1920 IWW meetings in Mexico City, which involved both factions, that the IWW’s US rule excluding non-wage-workers be

enforced. The observation of that rule would have meant the expulsion from membership in the Mexican IWW of Gale, the newspaper publisher and his followers: Cervantes López, the printer; Hipólito Flores, the policeman, and other non-worker members of Gale’s committee. Gale responded

evasively that the IWW had to organize soldiers and sailors, and should not, for example, exclude a woman fired from her factory who became a fruit vendor.36

36 Gale 1920, p. 6; ‘Memorandum to the A.C. of S. for Military Intelligence’, 15 October 1920, in

Box 2290, Record Group 165, USMID, USNA, an account of these differences within the IWW, probably written by José Allen, says that Pedro Coria was disputing the leadership of the union with Gale and Charles King. This is probably the same struggle. See also Taibo II 1986, p. 101.

There was another important element in this debate, in addition to the question of a member’s social class. Levine and Coria also proposed to take the Mexican IWW into an alliance with the anarchists, anarcho syndicalists, and the other Mexican Communist Party (not the one run by Gale) in order to form a united front among all the labor radicals in Mexico. It was this issue that accounted for the presence at the Mexico City meeting of Jacinto Huitrón, a leader of the anarcho-syndicalist labor

movement, and Manuel D. Ramírez, a labor activist and the future head of the Mexican Communist Party. It was this group which would later establish the important though short-lived labor organization the Communist Federation of the Mexican Proletariat.37

37 ‘Memorandum to the A.C. of S. for Military Intelligence: Notes on Radical Activities’, 15

October 1920, USMID, Record Group 165, Box 2290, USMID, USNA.

The debate over the rules was postponed, but Gale refused to call another meeting, so the other faction, Levine, Coria and King, now joined by Gale’s former allies Rodríguez, Pacheco and Ortega, called their own meeting of the executive board, revised the rules to exclude non-workers, and elected their own executive committee. Gale was out. Levine had won.

The Gale-Levine faction fight ended in the pages of the IWWs magazine in the United States at the end of 1920. In December, an article apparently written by Herman Levine, announced the victory of

the “wage workers” over the “petit bourgeois” faction led by Linn Gale. “The wage workers faction, the most numerous and the strongest, with the general secretary treasurer and the majority of the G.E.B. [General Executive Board] with them, are continuing in charge of the organization, and hope for better progress now that they have rid themselves of the political and petit bourgeois element,”, stated the author. The IWW, now firmly in proletarian hands, the author reported, was organizing oil workers in Tampico, metal mine workers in Guanajuato, and industrial workers in Mexico City.38

38 Herman Levine, Herman ‘The Mexican I.W.W.’, The One Big Union Monthly, December 1920, p. 57.

After Levine, Coria, and King took charge of the IWW, it immediately entered into a united front with the other factions of the revolutionary labor movement. The anarcho-syndicalists, the IWW, the Mexican Communist Party, and some independent unions formed first the “Revolutionary Bloc,” in August 1920, which subsequently became the Communist Federation of the Mexican Proletariat (FCPM). The FCPM was meant to be an alternative to the CROM. It stood for revolutionary labor

unionism, the fight for workers’ control, the overthrow of capitalism, and, passing through a brief dictatorship of the proletariat, for Social Revolution. While most of its members were anarchists or anarcho-syndicalists, the FCPM sympathized with the Soviet Union. Later the FCPM would become the anarchist General Confederation of Workers or CGT.

In addition to Levine’s wing of the IWW, the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) (that is the party founded by Roy and Phillips) also joined the new federation. Within a few months the PCM Communists were involved in the leadership of a genuine working-class upheaval in Mexico City,

Veracruz, Orizaba and Tampico. Two of the PCM’s new young leaders, Manuel Díaz Ramírez and José C. Valadés were elected secretaries of the executive board of the FCPM.39 The Communist Federation and its activists such as Levine, Valadés and Díaz Ramírez were far more serious about

organizing than Gale had been. For example,

39 Taibo II 1986, Los Bolshevikis, p. 103.

Díaz Ramírez, who was himself from Veracruz, contacted Aurelio Medrano and other leaders of the Orizaba textile workers’ anarcho-communist group, the group with which Gale had been corresponding. Díaz not only wrote them and sent the Communist magazine Vida Nueva and the

Boletín Comunista, but he also went to Orizaba gave a public lecture on “Unionism and Communism.” He met privately with local activists and attempted to win the group over to the Communist Federation of the Mexican Proletariat, and to the Mexican Communist Party.40 Díaz urged the local anarcho-communists and CROM activists to join the Communist Federation and later its successor the General Confederation of Workers (CGT). The Orizaba group decided to stay in the CROM, though they remained in its left wing.41 Nevertheless, Díaz and the Communists demonstrated a new commitment to building the IWW and the Communist Party among workers.

40 García Díaz, Bernardo 1990, Textiles del Valle de Orizaba (1880–1925). (Xalapa, Veracruz: Universidad Veracruzana, Centro de Investigaciones Historicas, 199), pp. 240–1.

41 Ibid., pp. 270–1.

Deported and jailed

Levine’s organizing in Tampico and his fight with Gale had strengthened the IWW in Mexico. He also helped to build the young and fragile Mexican Communist Party. The political winds, however, had shifted. While President Venustiano Carranza had welcomed the American slackers, the new president, Álvaro Obregon, wanted to be rid of them, ordering their arrest and expulsion.

Levine was captured and deported on 25 May 1921.42 He either revealed his citizenship or it was discovered, for the Washington Post carried the news of Levine’s detention to the public in a story

date-lined Laredo, Texas, 27 May 1921: Herman M. [sic] Levine, of New York City, who fled to Mexico in 1918 and is alleged to have engaged in radical activities there, was deported Wednesday from Monterrey, where he was arrested last week. He was immediately taken in charge by military authorities here and is being held at Fort McIntosh.43

42 Letter from Matthew C. Smith, Col., General Staff, Chief, Negative Branch to W.L. Hurley, Office of the Under-Secretary, Department of State, 28 May 1921; Memorandum for file dated 27 May 1921 regarding phone call from Mr. Hoover to USMID. Both in Box 2292, Record

Group 165, USMED, USNA.

43 “Mexico Deports Radicals; Herman M. Levine, of New York Returned to the United States,” Washington Post, 27 May 1921. Clipping in Box 2291, Record Group 165, USMID, USNA

.

44 Memorandum for file, undated by citing General Intelligence Bulletin No. 53 for 4 June

1921, Box 2292, Record Group 165, USMID,USNA.

The US government’s General Intelligence Bulletin No. 53 for 5 June 1921 reported that Levine’s “case will be presented to the Grand Jury for indictment as a slacker.”44

After this point, Levine disappears from the records, but what an experience Levine had had since the day four years before when he decided to resist the draft. The war and the draft forced him to give up his profession, and his country and led him to become a political exile in Mexico. While

Levine remained a radical, the war also caused him to abandon his political party, the Socialists, and led him to adopt the revolutionary syndicalist ideology of the Industrial Workers of the World.

As a Wobbly in Mexico, Levine edited the union’s newspaper in Tampico where he also became one of the union’s leading spirits. Of all the American slackers, Levine was perhaps the only one who really threw himself shoulder-to-shoulder into the organization of ordinary Mexican workers in an attempt to bring about a new industrial and economic order. For a brief period, Levine and his IWW ‘fellow workers’ had led thousands of Tampico’s oil port workers in a mass movement involving strikes that paralyzed shipping, challenged the employers, and troubled two states. Levine had cooperated with the founders of the Mexican Communist Party and Levine himself appears to have become a member. Like other radicals in Mexico at the time, Levine signed his letters “Salud y Revolución Social,” that is, “Health and Social Revolution,” and he added in English with that characteristic Wobbly American accent, “May it come damn quick.” Unfortunately for Levine, it did not come.

Whatever happened to Levine? We do not know, but a cross-reference in the card index of the US Military Intelligence Division files mentions a Herman Levine who was active in June 1932 in the

executive councils of various veterans’ organizations and was a bonus marcher, one of the largest American working-class protests of the era. Could that have been the Brooklyn school teacher Levine who led oil workers in Tampico during the years of the World War and the Mexican Revolution?

We cannot be sure that this is the same man, but it might well have been.