New Jersey Council for the Social Studies

Engaging High School Students in Global Civic Education Lessons in U.S. History

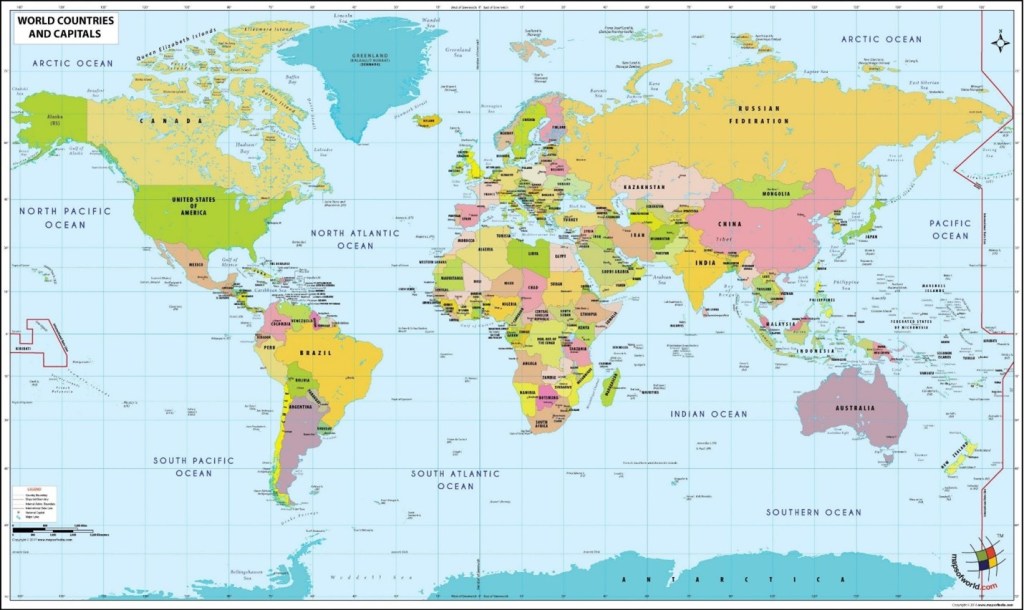

The relationship between the individual and the state is present in every country, society, and civilization. Relevant questions about individual liberty, civic engagement, government authority, equality and justice, and protection are important for every demographic group in the population. In your teaching of World History, consider the examples and questions provided below that should be familiar to students in the history of the United States with application to the experiences of others around the world.

These civic activities are designed to present civics in a global context as civic education happens in every country. The design is flexible regarding using one of the activities, allowing students to explore multiple activities in groups, and as a lesson for a substitute teacher. The lessons are free, although a donation to the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies is greatly appreciated. www.njcss.org

Era 16 Contemporary United States: Interconnected Global Society (1970–Today)

We are in the second quarter of the 21st century. Critical issues for governments center around fairness of elections, gender issues, food stability, artificial intelligence and intellectual property, and trade. The importance of collective security through alliances and the ability of international organizations like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund depend on leaders in countries supporting them and following their decisions.

Activity #1: Voting Rights and LGBTQ Individuals: Nigeria and the United States

Nigeria

Nigeria is the largest country in Africa with a population of 240 million. Its population growth rate is almost 3% with a projected population of 350 million by 2050. More than half of the population lives is cities. Nigeria has a diverse population with about 55% confessing Islam and 45% Christian beliefs.

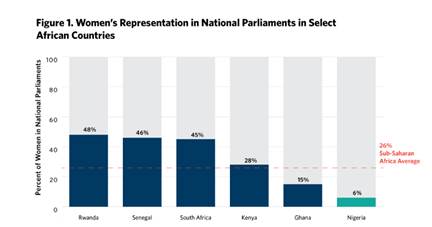

The Nigerian Constitution Amendment Act of 1954 eliminated gender restrictions on voting and allowed men and women to engage in the political process equally. Unfortunately, the patriarchal culture that existed before Nigeria became independent and the influence of Muslim beliefs on the role of women are two factors restricting the civic engagement of many women.

In 2022, the Nigerian Congress passed legislation making voting in state and national elections mandatory for all Nigerians eligible to vote. Voter apathy is a problem and coercion is the strategy by the current government to address this issue. In 2023, only 27% of registered voters participated in the national election. President Tinubu signed the Electoral Act of 2026, which fines and arrests citizens who do not exercise their right to vote.

The Electoral Act 2026:

- Formalizes the use of the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) as the sole mandatory method for voter accreditation, officially replacing older technologies.

- Streamlines election administration by adjusting the “Notice of Election” window to 180 days and requiring the submission of candidate lists 90 days before a general election.

- Increases the fine for the illegal buying or selling of Permanent Voter Cards (PVCs) to ₦5 million, maintaining a strict two-year imprisonment term for offenders.

- Grants the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) the authority to prescribe the specific manner for the transfer of results and accreditation data, ensuring operational flexibility in areas with varying infrastructure.

President Tinubu stated. “We are ensuring that the voice of every Nigerian is not only heard but accurately recorded and protected by the law.” The 2026 Electoral Act is based on the premise that a high voter participation rate reduces election fraud. Singapore, Australia, Argentina, and Brazil also require mandatory voting and voter participation is 80% or higher. These countries also have secure, trusted, and efficient systems in place.

Although the Act provides for transparency through digital reporting of election results, the Act includes a provision for the manual submission of election results in areas where the technology is not available or reliable. The 2026 Act also maintains the Permanent Voter Card (PVC) as the mandatory identification for voting. The Constitution (Section 40) states that the right not to participate in voting is as important as the right to vote.

However, not everyone agrees with this position because it may increase voter apathy. Voting must be a choice freely made, not forced by threat of jail. The law is also viewed as unconstitutional because Chapter 4: Section 40 provides for the right not to participate in elections. The new law does not address the problems of insecurity and lack of credibility in political leadership, and buying votes.

LGBTQ+

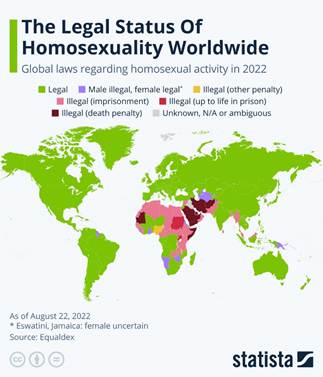

Nigeria is a conservative country with a history that has made homosexuality and lesbianism illegal. The Islamic and Christian religious beliefs in Nigeria oppose homosexuality and lesbianism. It is estimated that there are 15-20 million Individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ and are subject to arrest, which is often accompanied by police violence and brutality. LGBTQ+ individuals are victims of assault, mob attacks, harassment, extortion, and the denial of basic rights and services. As a result they are living in hiding.

In 2024, President Tinubo approved an order preventing LGBTQ+ individuals from serving in the armed forces. In 2014, the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act 2013 (SSMPA) came into force. The Act includes criminal penalties for same sex marriages or civil unions; solemnizing a same-sex marriage or union; “gay clubs, societies or organizations”; and same sex amorous relationships in public. Sharia law in the 12 northern States criminalizes same-sex intimacy between both men and women, as well as cross-dressing. These recent actions mark an aggressive effort by the government against LGBTQ+ individuals.

United States

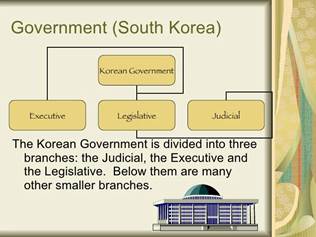

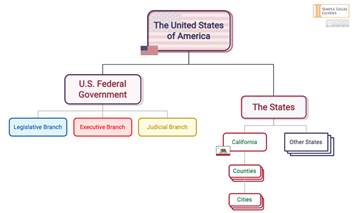

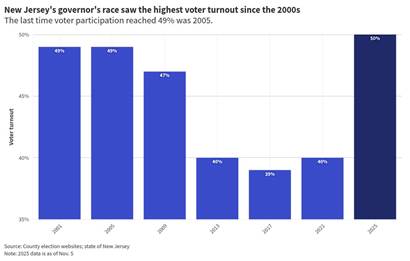

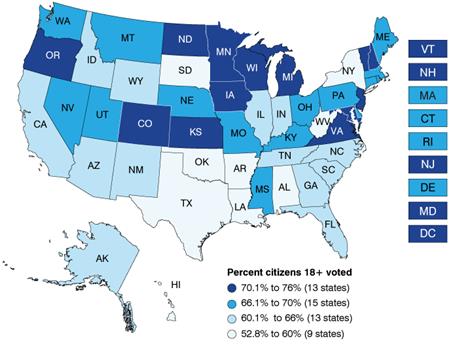

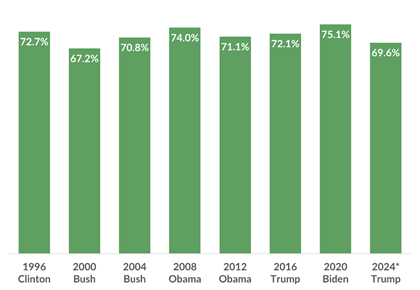

The United States amended its constitution four times (Amendments #15, 19, 24, and 26) to increase voter participation and establish a fair and efficient process for elections. The Constitution delegates elections to its 50 states, with the exception of the date in November for the national election of president every four years. The United States has a long history of expanding voter registration, participation in elections, and encouraging civic engagement. Although voter participation is around 50% in general elections, the participation rate to elect the president every four years is about 70%.

In 2013, the 5-4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, marked a turning point in the election laws in the United States. The decision was that states and localities with a history of suppressing voting rights no longer were required to submit changes in their election laws to the U.S. Justice Department for review.

As a result. Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Virginia passed legislation requiring voter identification to vote.

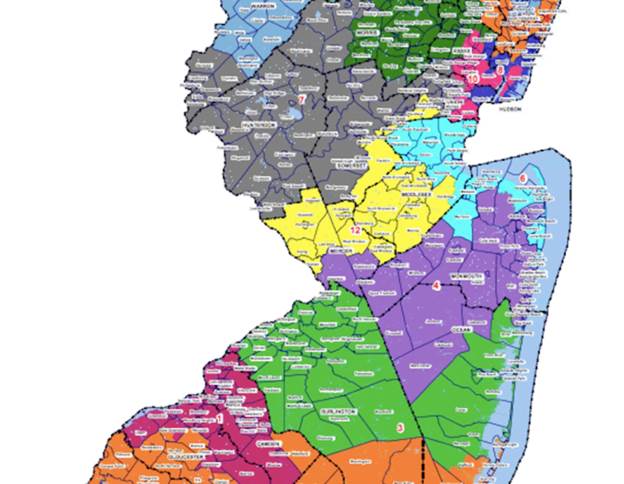

Although the United States is viewed as a country with fair elections, the incumbent administration of President Trump claims it is not fair, influenced by foreign governments, and to rewrite election rules. Some states have attempted to change their congressional districts to favor one party over another. This process is called gerrymandering and takes place every ten years based on the data provided by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The major changes currently being attempted in the United States include:

- rewriting election rules to control election systems;

- threatening to target election officials who keep elections free and fair;

- supporting people in the states who question the current election administration;

- retreating from the federal government’s role of protecting voters and assuring fair elections.

LGBTQ+

The U.S. Supreme Court extended LGBTQ+ rights after the Stonewall riot in 1967. However, in 1996, Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act banning federal recognition of same-sex marriage by defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman. It also allowed states to refuse to recognize a same-sex marriage granted by another state. In 2022, the Defense of Marriage Act was repealed by the passage of the Respect for Marriage Act which recognizes the validity of same-sex and interracial civil marriages in the United States. The Respect for Marriage Act received support following the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges 5-4 decision which stated that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause requires states to license and recognize marriage between two people of the same sex.

Questions:

- How can governments increase voter participation and civic engagement?

- Do the attempts in Nigeria to require eligible voters to vote support or hinder democracy and civic participation?

- Should the Electoral Reform Act of 2022 and the Amendment (2026) be viewed as supporting democracy or limiting democracy?

- Does Voter Identification requirements enure fairness in elections or suppress voter participation?

- In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court’s controversial 5-4 decision in Bush v. Gore established a precedent for determining the outcome of a close election (271 – 266). If a future election is questioned in the United States, how should the outcome be decided?

- In the United States, should the federal government or the states have the authority to license and recognize marriages?

- Do individuals in Nigeria, who identify as LGBTQ+, have any protections from physical abuse by the government? Where would they begin?

Resources:

Nigeria Constitution (Chapter 4: Section 40) (Action for Justice)

Women’s Inclusion in Nigerian Politics: A Data-Driven Approach

Electoral Bill 2026 (The Guardian)

Nigeria: Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (U.S. Department of Justice Report)

The Trump Administration’s Campaign to Undermine the Next Election (Brennan Center for Justice)

Preserving and Protecting the Integrity of American Elections (The White House)

LGBTQ+ Rights and U.S. Supreme Court Cases (Justia)

Activity #2: Copyright Protection: Kenya and the United States

Kenya

Kenya updated the Copyright Act of 2001 in 2020 and amended it in 2022 and 2026 because of the unique challenges in the arts and creative markets. Kenya realized the potential of the creative arts industry in their economy. The amendments offer protected rights to authors for 50 years after their death and 50 years after the work was first created.

The primary purpose of copyright protection is to safeguard the rights of authors and creators. Kenya’s laws encourage new artistic and intellectual content. The Copyright Act also defines how the works are reproduced, distributed, and publicly displayed. The fair use doctrine allows for limited usage of copyrighted materials for criticism, news reporting, education, and research. A unique provision in the Act provides for moral rights protecting the creator’s identity.

You may want to read the court case of Kimani v Safaricom Limited regarding use of intellectual property from other parties.

United States

The U.S. Constitution provides for copyright protection in Article I, Section 8, Clause 8. The United States update the Copyright Act of 1976 in 2025 with provisions for intellectual property, and semiconductor chips. The United States issues licenses for creative, artistic, and technology authors. The United States protects the rights of authors for 70 years.

One of the core functions of copyright law is to grant exclusive rights to creators, allowing them to control how their works are used, reproduced, distributed, and displayed. These exclusive rights include the right to reproduce the work, prepare derivative works from another source, distribute copies, and perform or display the work publicly. Copyright laws provide financial incentives and protect the integrity of creative and artistic works from duplication, alteration, or diminishing the creator’s reputation.

Copyright protection supports cultural, educational, and technological advancement by encouraging authors to write books, musicians to compose songs, films to be produced, and developers to create software. This cycle of creation and protection benefits society as a whole, enriching public knowledge and entertainment while fostering economic growth in creative industries. These laws must also protect the public interest to use the content in these protected products for education and research. You may want to read the court case decision regarding the use of the Happy Birthday song.

Questions:

- Should artists receive royalties when their music is played on the radio or only on subscription based platforms?

- What is a reasonable number of years for copyright protection?

- Should information and content generated by artificial intelligence and not a human be protected by copyright laws?

- How should the public interest of content protected by copyright laws be defined? For example, should a child be able to play a popular song in their home without paying a royalty and should a student or teacher be allowed to download an image or select a paragraph from a published book for free?

- What should educators teach about copyright laws and citing sources and in what grade should these be taught?

Resources:

Kenya Copyright Law, 2020 (Kenya Law: The National Council for Law Reporting)

Kenya Copyright Act, 2022 (Kenya Institute for Public Policy and Research Analysis)

Kimani v Safaricom Limited (Civil Case, 2023)

United States Copyright Law: Issues for Congress (Congressional Research Service)

Landmark Musical Content Infringement Cases in the United States (University of Oregon)

Activity #3: The Nile River and the Environment: Ethiopia and Egypt

Egypt

In September 2025, Ethiopia began diverting water from the Nile River with the operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. (GERD) The Nile River is the longest river in the world (although some claim the Amazon River is the longest) and is a vital resource for millions of people in Sudan and Egypt who depend on it for potable water, agriculture, fishing, navigation, and tourism. Ethiopia built the dam as a vital source of energy, flood control, and to support the economic development of the region.

Egypt claims the dam violates international law governing international waterways and is a violation of the human rights of its people. Studies provide evidence that any significant decrease in Egypt’s share of the Nile River water will lead to a decline in food production and increase poverty. However, these violations were also used to criticize the Awan Dam built on the Nile River in 1970. The Aswan Dam has prevented serious flooding, provided economic growth, and is a vital source of clean energy. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is more than doubles the hydroelectric power of the Aswan Dam.

Aswan Dam

Ethiopia

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is the largest hydropower project in Africa. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project has generated significant occupational and social impact as it was financed and built by the people of Ethiopia. The plant also ensures a reduction of 1.3 million tons of carbon emissions per year. The complex includes three housing developments for 10,000 people, three medical centres and schools, food stores, recreational areas, a club, a swimming pool, and sports fields.

The dam produces more electricity than Ethiopia needs providing for the possibility of exporting clean energy to Djibouti and Kenya. It was constructed with the expectation that this will enable economic growth in Ethiopia for manufacturing, technology, and food production.

Questions:

- Does a country have the right to make a unilateral decision that affects international waters?

- Are the economic and environmental benefits of clean energy greater than the disadvantages of water flowing to neighboring countries?

- The Nile River is known for transporting sediment in its journey of approximately 3,000 miles. Will this sediment prove harmful to the Greater Ethiopian Renaissance Dam over time?

- Does Ethiopia have a promising or a disappointing future? What is your prediction for Ethiopia in 2050?

Resources:

The Impact of the Renaissance Dam on the Right to Water and Sustainable Development in Downstream Countries (United Nations Human Rights Council)

The Controversy Over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Brookings)

Ethiopia Outfoxes Egypt over the Nile’s Waters with its Mighty Dam (BBC)

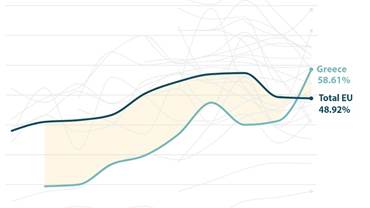

Activity #4: Trade: European Union and the United States

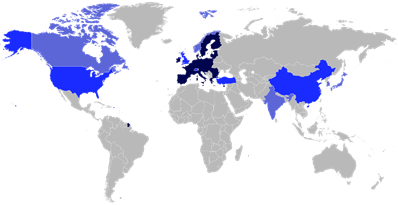

The economies of the European Union and the United States are fairly similar in size. Between 1950 and 2025, the countries of the Europe were major trading partners with the United States. Beginning in 2025, this relationship changed as the United States levied tariffs on many products exported to the United States.

The EU is the largest economy in the world with a GDP per head of €25,000 for its 440 million consumers and the volume of trade represents 29% of global trade. It is the world’s largest producer of both manufactured goods and services. They are the top trading partner for 80 countries and the United States is the top trading partner for about 20 countries. The 27 countries in the European Union had a trade surplus of $272 billion (USD) in 2024. The major exports are machinery, computers, vehicles, pharmaceuticals, plastics, optical equipment, organic chemicals, and iron, steel. The major imports are vehicles and oil.

United States

Mexico and Canada are the largest trading partners for the United States representing 30% of trade. China, Germany and Japan account for 20%. The United States has a trade deficit with all of its top 15 trading partners with the exception of a surplus with the United Kingdom and Netherlands. In 2025, the annual trade deficit of the United States was $901.5 billon.

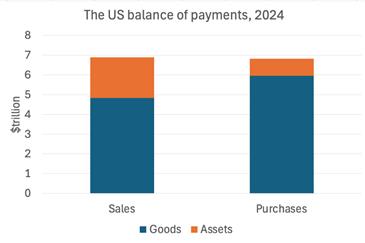

A trade deficit is often misleading and students need to analyze it from different perspectives. First, the Current Account represents the net value of trade and the Capital Account represents the value of assets, including property, investments, and foreign aid. Together, these two accounts are called the balance of payments. The current account is always offset by the capital or financial account so that the sum of these accounts – the balance of payments – is zero. When the balance of one account is in surplus (i.e. has a positive value, representing a credit), the balance of the other account must be in a deficit (i.e. has a negative value, representing a debit). The Current Account and the Capital Account are different from the national debt of $39 trillion or annual deficit of $1.8 trillion for the United States. The national debt and annual deficit directly affect the credit rating of a country and the value of its currency.

Questions:

- Why does one country purchase goods or services from another country when the result is a trade deficit?

- President Trump has issued tariffs against countries that the United Staes has a trade deficit with. How does this affect trade and the Current Account in the future?

- Will the new trade strategy of using tariffs and incentives for companies to manufacture in the United States lead to more economic growth and employment or higher prices and a recession?

- How serious is a trade deficit for a country? As an advisor to the President of the United States would you favor a strong or weak currency?

- How did the European Union become the world’s largest economy?

- Are there lessons for the United States to consider regarding a North American Union or a Western Hemisphere Union of free trade?

Trade and Economic Security (European Commission)

International Trade in Goods (EuroStat)

European Union Trade Summary, 2023 (World Bank)

U.S. Foreign Trade (U.S. Census Bureau)