The History of the Lenni-Lenape Before, During, and After the American Revolution

(Image courtesy of Legends of America)

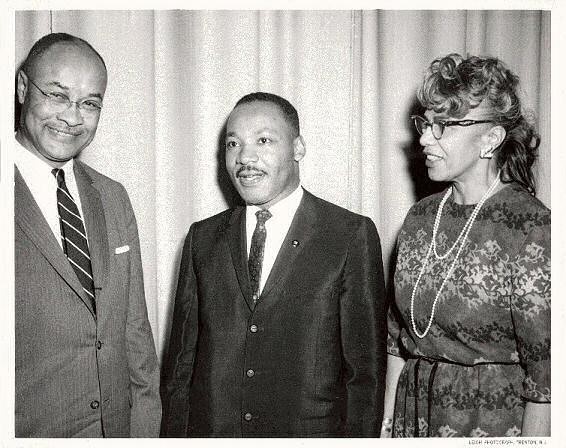

By Mr. David A. Di Costanzo, M. Ed Social Studies Department Chair Vineland High School

Introduction:

During the first year of this grant, seven Social Studies teachers from around the state conducted research for the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies (NJCSS). The teachers examined the histories of ordinary people in New Jersey and how the events leading up to and during the Revolutionary War impacted their lives. The grant, “Telling Our Story: Living in New Jersey Before and During the American Revolution”, is an ongoing effort by the NJCSS to prepare educators in New Jersey for the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution during the 2025-26 school year. The 250th anniversary celebrations will continue through 2031 and is part of the overall mission of the NJCSS to provide and make available meaningful lessons and activities to students, teachers, and the public.

During Year Two of the grant, the focus of the research has shifted to include the role and contributions of African Americans, Native Americans, and prisoners of war before, during, and after the American Revolution. An emphasis on the experiences of women and children during this time period will also be researched. The lives of the Lenni-Lenape from New Jersey before, during, and after the American Revolution is a fascinating and important part of American history. Professor of History and Native American Studies Colin G. Calloway from Dartmouth University said, “with few exceptions, the Indian story in the Revolution remains relegated to secondary importance and easy explanation: The Indians chose the wrong side and lost. To better understand the reality of the Revolution for American Indians, we need to shift our focus to Indian country and to the Indian community.” [1] Sadly, the story of the Lenni-Lenape during this time period has been “relegated to secondary importance” and not been told enough.

The role of Lenni-Lenape is crucial in our understanding of the American experience. What was lifelike for the Lenni-Lenape in New Jersey? Unfortunately, the Lenni-Lenape, dealt with racist mindsets which were the primary impetus that led to a negative and mostly superficial historiography of their culture that took centuries to completely shift. Historical perceptions and the racial mindsets of Native Americans did eventually change but only after they were deprived of their land, forced to live on reservations, and required to assimilate into mainstream American culture.

It’s also important to note that for Native Americans the Revolutionary War began way before Lexington and Concord. Most historians agree that the American Indians had been fighting for their own independence since the Europeans made contact. Accepting and embracing the fate of the Lenni-Lenape and discovering how people lived before and during the American Revolution in New Jersey is important work. It allows students and residents in various counties throughout New Jersey to discover a more objective truth about Native Americans before and during the American Revolution. This more objective truth is an honest attempt to provide greater transparency for everyone, whether they agree with it or not.

Historical Background:

The cultural history of Native Americans is interesting for a variety of reasons. The treatment of Native Americans is viewed by most historians as horrific. Native Americans were systematically excluded from having a true voice during European exploration and colonization as well as after the United States was founded. The explorers ravaged the indigenous people of this continent with violence, disease and deprivation. Native Americans had non-Christian spiritual beliefs which went against the religious doctrine of the early explorers. This difference in cultures created a severe spiritual divide. Later on, colonists traded with Native Americans but European settlers viewed them as nothing more than savages and barbarians.

By the nineteenth century, Native Americans had no choice but to assimilate in order to survive. Forced assimilation in order to survive is not the same thing as having a legitimate stake in the system. Time has made most ethnicities, including American Indians, a larger part of the American landscape. All of these factors created a system of severe limitations for most Native Americans that still lingers today. The situation in New Jersey regarding the treatment of the Lenni-Lenape was similar to the way Native Americans were dealt with throughout the colonies and the United States.

The Lenni-Lenape of New Jersey are descendants of the Paleo-Indian whose history on this continent has been traced back to 13,000 years ago. The Lenni-Lenape were also referred to as the Delaware Indians by the English and the Dutch. Professor of History Maxine Lurie from Seton Hall University and Professor of Anthropology Richard Veit from Monmouth University said, “the first settlers to reach what is now New Jersey probably did so during or before the Paleo-Indian period. Archaeological sites from this period are quite rare.” [2] Nevertheless, Paleo-Indian artifacts have been found across New Jersey as well as in New York and Pennsylvania. Excavations during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries confirmed the presence of Paleo-Indians throughout New Jersey.

Various cultural periods would ensue for the next several thousand years leading to the final phase prior to European contact which is referred to as the Woodland Period. This period began roughly a thousand years ago and continued until contact with Europeans during the early sixteenth century. [3] The earliest reports of contact with European explorers occurred in 1524 when Giovanni da Verrazano explored the Atlantic coast of North America. He described the natives in and around what today is New Jersey as “most loving”. [4] Contact with whites was sporadic until the early 1600’s. The interactions with the Lenni-Lenape and the explorers increased and progressed during the early seventeenth century and beyond.

The Dutch and English had a sincere desire to trade with the American Indians from the Garden State. It’s well documented that, “the Dutch West India Company, formed in Holland in 1621 to develop commerce, especially fur trading, constituted the present New Jersey Hudson River area into the province of New Nether (often “New Netherlands”) in 1623.” [5] Furs, cooper, and other perishable commodities, such as alcohol, were all eagerly exchanged. It became clear almost immediately that most Native Americans didn’t react well to the consumption of alcohol. This inability to consume alcohol in moderation was something European traders would quickly learn to take advantage of without hesitation. The Dutch and English traded with the Lenni-Lenape of New Jersey in spite of the animosity and racism that existed. Most Dutch traders had very little respect for the American Indians.

This map is from John Snyder’s The Story of New Jersey Civil Boundaries 1202-1968

This map shows various Indian trails that crisscrossed New Jersey. The Assunpink Trail goes from the lower left on the Delaware River and continues northward, crosses the Raritan River and heads for Staten Island.

An unintended consequence or impact of European exploration was the massive spread of numerous diseases. Professor Lurie and Professor Veit, said that in and around New Jersey

“The impact of disease on Native American populations was disastrous. Population estimates for the Lenape vary significantly, with some scholars arguing for 12,000 natives at the time of European contact and others for much smaller numbers. In the seventeenth century smallpox epidemics, malaria, measles, and influenza significantly reduced the Native American population” [6]

Like all of the other Native American tribes in North America, disease had a devastating effect on the Lenni-Lenape of New Jersey that would linger on for decades. It put the indigenous people of this continent at a serious disadvantage from the beginning of their contact with the Europeans.

In spite of the effects of alcohol and disease on the Lenni-Lenape of New Jersey, they maintained a serious control of trade during most of the seventeenth century. Professor of History Jean Soderlund from Lehigh University said that

“Because of mythology, the Lenape are often portrayed as a weak people lacking the numbers and fortitude to defend their homeland. The prevailing narrative ignores the period of 1615-1681 when the Lenape dominated trade and determined if, when and where Europeans could travel and take up land.” [7]

Except for the Pavonia Massacre in February of 1643, the Lenni-Lenape avoided major conflicts during this time period. This was in stark contrast to the Anglo-Powhatan War and Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia which were both larger in terms of the number of people that were killed. [8] The Pavonia Massacre was the first known attack led by Dutch soldiers that saw over one hundred Native American men, women, and children slaughtered in the area of what is today Jersey City. After the massacre, hostilities would remain for almost three years until a truce was agreed to in 1645.

A Depiction of the Pavonia Massacre in 1643 (Image courtesy of Timetoast)

Professor Soderlund said “the Lenapes’ firm grip on south and central New Jersey is clear in a map from 1670 created by a merchant named Augustine Herrman, who had settled in New Amsterdam in 1644 and then established his plantation, Bohemia Manor, on the Maryland Eastern Shore in 1661.” [9] The map below shows New Jersey illustrated on the lower right-side of the map. Numerous Lenape populated the area shown on the map that constitutes most of present-day New Jersey. This map is definitive evidence of the control the Lenni-Lenape had over New Jersey during the late seventeenth century.

A map by Augustine Hermann of Virginia and Maryland and New Jersey as it was planted and inhabited in 1670, W. Faithorne, sculpt. (Map courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The Lenni-Lenape had an interesting relationship with the Quakers, especially in West Jersey. The influence of the Quakers could be felt throughout New Jersey during the colonial period. Professor of History Richard McCormick from Rutgers University said

“Lacking the peculiar fervor that had stamped them as religious radicals in the previous century, the Quakers manifested increasing concern with social problems and took leadership in many areas of humanitarian reform. Impelled by that saintly friend, John Woolman, of Mount Holly that came out firmly against slave holding in 1758, displayed a deep concern for the plight of the Indians, developed a system of education, and even began to withdraw from political activities because of their opposition to the war and military preparations.” [10]

Unfortunately, the Quakers, as well as other religious groups were guilty of displacing the Lenni-Lenape particularly in West Jersey and in Pennsylvania. Professor McCormick made it clear that the Quakers weren’t transparent with the Native Americans of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, including the Lenni-Lenape, in various land deals.

During the eighteenth century, the relationship between the Lenni-Lenape and the colonists would continue to deteriorate. Land ownership became a major issue throughout New Jersey, as well as the rest of the colonies, as the English took over control and established their dominance throughout the continent. Several Lenape chiefs attempted to secure land deals with the New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware colonies. These efforts culminated in the Walking Purchase of 1737. Chief Tishcohan (or He Who Never Blackens Himself) was one of the signers of the Walking Purchase of 1737, a treaty with the Penn family that later caused the Lenape to lose most of their land in the Delaware Valley. It’s certain that “the infamous Walking Purchase defrauded them of considerable land in eastern Pennsylvania. The Walking Purchase led to years of recriminations and bad feelings. [11]

Delaware Chief Tishcohan

Tishcohan by Gustavus Hesselius. A 1735 portrait of the Delaware chief Tishcohan, commissioned by John Penn. William Penn’s son. (Portrait courtesy of the Millstone Valley Scenic Byway)

Another victim of the Walking Purchase, Chief Teedyuscung would eventually leave New Jersey and make his way to Bensalem and align himself with the Moravians. Prior to the American Revolution Chief Teedyuscung would be killed by white vigilantes. These killings made it clear that it was in the best interest of the Lenape to continue moving west. The legacies of both Chief Tishcohan and Chief Teedyuscung include their efforts in trying to preserve the culture and legal rights of the Lenape.

Chief Teedyuscung

A depiction of Teedyuscung (Image courtesy of the Wissahickon Valley Park)

The role of religion became even more prominent during this time period. Missionaries from various Christian faiths made attempts at converting numerous Native American tribes including the Lenni-Lenape. Associate Professor of History Linford D. Fisher from Brown University said “the rich, overlapping worlds of Native spirituality and Christian practice, one in which the rituals, symbols, and beliefs of European Christianity were adopted by Indians over time, either voluntarily or in response to the overtures of English missionaries.” [12]

One missionary, David Brainerd, played an important role in attempting the religious conversion of the Lenni-Lenape. Professor Lurie and Professor Veit said that “Presbyterian missionaries also were active among the Delaware. In 1745, David Brainerd, a young Presbyterian minister who belonged to the New Light faction of the church, which emphasized personal salvation and evangelical zeal, began mission work among the Lenape.” [13] David Brainerd died in 1747 and was succeeded by his brother John who held similar beliefs regarding personal salvation and missionary work. John Brainerd would be instrumental in the conferences the New Jersey Colonial government held in 1756 and 1758 in which the colony attempted to address the Native Americans consumption of alcohol and made clear the process for selling Indian lands. [14]

Throughout the French and Indian War, countless Native American tribes fought on the side of the British and the French. Numerous tribes, including the Lenni-Lenape of New Jersey, signed the Treaty of Easton of 1758. Part of the treaty included a provision that the Lenni-Lenape avoid alliances with the French during the war. They also had to forfeit their eastern lands. In return, the British promised to stop expeditions into Indian territory west of the Alleghenies. As a result, many Lenape left New Jersey. It was around this time that New Jersey created its first Indian reservation, which was called “Brotherton,” and was located in the present-day Indian Mills section of Shamong in Burlington County. Reverend John Brainerd assisted in the settlement of the reservation. [15] A result of the Treaty of Easton was the establishment of a permanent home for the Lenape that initially saw some success but was ultimately unsuccessful.

The Native Americans throughout the colonies had a very distinct role during the American Revolution. Professor Wilcomb E. Washburn, the former Director for the Smithsonian’s American Studies Program said, “it was a shadowy role, but an important one. It was shadowy not only because the Indian operated physically from the interior forests of North America and made his presence felt suddenly and violently on the seaboard settlements, but because the Indian was present also in the subconscious mind of the colonists as a central ingredient in the conflict with the Mother Country.” [16] The British and the Colonists made numerous attempts to form alliances with various tribes throughout the colonies. There was some success in getting the Indians to align with one side or the other.

The Lenni-Lenape from New Jersey had already begun to leave by the start of the American Revolution. The Lenape were a divided people with only a small number remaining in the Garden State, while most moved north or west. [17] The Lenni-Lenape that remained in New Jersey during the American Revolution played a significant role. Professor Lurie said,

“During the Revolution, the western Delaware at first tried to stay neutral, but then split as some joined with the British, while others sided with the Patriots. Thus, this also became a civil war for them. The United States signed a treaty in 1778 with the chiefs who sided with the Patriots, but White Eyes, the strongest supporter, was murdered, promised supplies were not delivered, and villages of friendly natives were attacked. In the end, the results were disastrous for the Delaware, whichever side they took, as well as for members of other Indian nations.” [18]

Following the Revolution, the Lenni-Lenape of New Jersey suffered through more broken promises first by the British, who basically abandoned them, and then by the United States government. By the early nineteenth century, most of the Lenni-Lenape either integrated into the local communities in New Jersey or left the state. Many went to Canada or the Kansas Territory while others joined other Native American tribes such as the Cherokee. Others ventured west to “Indian territory” which is today Oklahoma.

During the nineteenth century, Native Americans, including the Lenni-Lenape, were instrumental in shaping abolitionism, both as participants in antislavery activities and as objects of concern. In fact, abolitionist support for Native Americans before the Civil War did exist. Unfortunately, it’s made clear that not all politicians from New Jersey supported both Native American rights and the abolition of slavery. Associate Professor of History Natalie Joy from Northern Illinois University said,

“Especially disappointing was New Jersey senator Theodore Frelinghuysen, among the most vociferous congressional opponents of removal and yet an avowed supporter of the American Colonization Society. Though they praised his “unwearied zeal in the cause of the injured and insulted Cherokees, abolitionists highlighted Frelinghuysen’s continued disengagement with the antislavery cause.” [19]

It appears that Congressman Frelinghuysen was against Indian removal but refused to support the abolition of slavery. This is not surprisingly particularly since New Jersey was the last northern state to abolish slavery following the Civil War. After rejecting the 13th Amendment, New Jersey did finally ratify it on January 23, 1866.

By the conclusion of the Civil War, many Lenni-Lenape were living in Kansas. Professor of History C.A. Weslager from Widener University said, “in the winter of 1866, the Department of Indian Affairs brought to Washington the chiefs and councils representing the Indian tribes living in Kansas for the purpose of persuading them to sell their reservations and move to new homes in what was then called Indian Territory, or even further west.” [20] Treaties were made with various Native American tribes including the Lenni-Lenape. The Lenni-Lenape sold or gave up their land holdings in Kansas and settled in Oklahoma.

Jennie Bobb, and her daughter, Nellie Longhat, both Delaware (Lenape), Oklahoma, 1915. (Photo courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington)

The remaining Lenni-Lenape that stayed in Oklahoma were the final collective remnants of a once proud, dominant, and successful people. Many had already assimilated into American culture by the end of the nineteenth century. Continued pressure from the United States government would force even more Lenni-Lenape to integrate into white communities. Sadly, this indigenous group, like the vast majority of other Native American tribes, were systematically deprived of their land, forced to live on reservations, and required to assimilate into mainstream American culture. Professor Weslager said, “by 1946, Congress established the Indian Claims Commission to act as a court and provide a regular means of adjudicating claims involving injuries to Indian tribal groups.” [21] Historians have surmised that this commission was essentially an admission of guilt by the United States Government. The Indian Claims Commission would go on to adjudicate hundreds of claims and award millions of dollars to various Native Americans. Reparations would be awarded to the Lenni-Lenape and start to be distributed during the late 1960s.

Conclusion:

The lives of the Lenni-Lenape from New Jersey before, during, and after the American Revolution is a fascinating and important part of American history. They were a thriving and successful culture until European contact. The Lenni-Lenape were able to remain successful in New Jersey for over a century after European colonization. The Lenni-Lenape had largely left by the beginning of the American Revolution. However, those who remained did play a role. During the American Revolution, there was some success in getting the Indians to align with one side or the other. Regardless, as the United States continued to develop and grow the Native Americans of this continent were deprived of their natural and lawful rights. Native Americans were systematically excluded from having a true voice during European exploration and colonization as well as after the United States was founded.

By the nineteenth century, Native Americans had no choice but to assimilate in order to survive. Forced assimilation in order to survive is not the same thing as having a legitimate stake in the system. Time has made most ethnicities, including American Indians, a larger part of the American composition. The role of Lenni-Lenape is crucial in our understanding of the American experience. Regrettably, the Lenni-Lenape, dealt with racist mindsets which were the primary impetus that led to a negative and mostly superficial historiography of their culture that took centuries to completely shift. Historical perceptions and the racial mindsets of Native Americans did eventually change but only after they were deprived of their land, forced to live on reservations, and required to assimilate into mainstream American culture.

Works Cited

Calloway, Colin G. “‘We Have Always Been the Frontier’: The American Revolution in Shawnee Country.” American Indian Quarterly 16, no. 1 (1992): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/1185604.

Fisher, Linford D. “Native Americans, Conversion, and Christian Practice in Colonial New England, 1640-1730.” The Harvard Theological Review 102, no. 1 (2009): 102.

Joy, Natalie. “The Indian’s Cause: Abolitionists and Native American Rights.” Journal of the Civil War Era 8, no. 2 (2018).

Lurie, Maxine N., and Richard F. Veit. New Jersey: A History of the Garden State. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2018.

Lurie, Maxine N. Taking Sides in Revolutionary New Jersey Caught in the Crossfire. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2022

McCormick Richard P. New Jersey from Colony to State 1609 to 1789. The New Jersey Historical Series, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey 1964.

Snyder, John Parr. The Story of New Jersey’s Civil Boundaries, 1606-1968. Trenton: New Jersey Dept. of Environmental Protection, Division of Water Resources, Geological Survey, 1969.

Soderlund, Jean R. Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Washburn, Wilcomb E. Indians and the American Revolution. Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.americanrevolution.org/ind1.php.

Weslager, C. A. The Delaware Indians: A History. Rutgers University Press, 1972.

[1] Calloway, Colin G. “‘We Have Always Been the Frontier’: The American Revolution in Shawnee Country.” American Indian Quarterly 16, no. 1 (1992): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/1185604.

[2] Lurie, Maxine N., and Richard F. Veit. New Jersey: A History of the Garden State. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2018, 11.

[3] Lurie & Veit, 16.

[4] Lurie & Veit, 18.

[5] Snyder, John Parr. The Story of New Jersey’s Civil Boundaries, 1606-1968. Trenton: New Jersey Dept. of Environmental Protection, Division of Water Resources, Geological Survey, 1969.

[6] Lurie & Veit, 20.

[7] Soderlund, Jean R. Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, 5.

[8] Soderlund, 5.

[9] Soderlund, 2.

[10] McCormick Richard P. New Jersey from Colony to State 1609 to 1789. The New Jersey Historical Series, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey 1964, 95.

[11] Lurie & Veit, 25.

[12] Fisher, Linford D. “Native Americans, Conversion, and Christian Practice in Colonial New England, 1640-1730.” The Harvard Theological Review 102, no. 1 (2009): 102.

[13] Lurie & Veit, 24.

[14] Lurie & Veit, 24.

[15] Lurie & Veit, 25.

[16] Washburn, Wilcomb E. Indians and the American Revolution. Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.americanrevolution.org/ind1.php.

[17] Lurie, Maxine N. Taking Sides in Revolutionary New Jersey Caught in the Crossfire. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2022, 107.

[18] Lurie, 8.

[19] Joy, Natalie. “The Indian’s Cause: Abolitionists and Native American Rights.” Journal of the Civil War Era 8, no. 2 (2018): 222.

[20] Weslager, C. A. The Delaware Indians: A History. Rutgers University Press, 1972, 421.

[21] Weslager, 457.