“Rights, Redistribution, and Recognition”:Newark and its Place in the Civil Rights Movement

Victoria Burd

New Jersey, a northeastern state situated directly under New York and steeped in American history, is often seen as a liberal beacon for the 20th and 21st centuries. The state has consistently voted Democrat in every presidential election for over twenty years, holds a higher minimum wage than many other states, and has decriminalized marijuana in recent years. Despite these “progressive” stances, New Jersey, like the rest of the United States, is mired by a history of racial injustice and discriminatory violence, often perpetrated by the hands of the state itself. New Jersey’s key cities such as Newark, Trenton, and Camden served as battlegrounds in a fierce fight for equality and justice, yet these cities remain an often forgotten fragment of the Civil Rights movement of the mid-20th century due to their location in the North.

Defining the Civil Rights movement is a difficult task, as Black Americans have been fighting against racism and discrimination in America for centuries before the term “Civil Rights movement” was even coined. For the purposes of this paper, the focus will be on the post-World War II Civil Rights movement, from the 1950s-1970s, where many famed protests and riots took place across the Northern and Southern United States. Large cities such as Newark, Trenton, Camden, and various others in New Jersey performed critical roles in the Northern Civil Rights movement, with Newark being one of the most publicized of its time. Acting as a catalyst to other race riots in cities such as Trenton and Plainfield, as well as being more thoroughly documented, the 1967 Newark riots serve as a case study by which to compare other cities in New Jersey, the events of the Civil Rights movement in Newark to other events in the North as a whole, and where Newark compares and contrasts with the Southern Civil Rights movement. This paper will explain the preceding events, context, and lasting effects of the 1967 Newark riots and the historiography existing around the Northern Civil Rights movement, before comparing and contrasting Newark and the Northern Civil Rights movement to that of the South and analyzing how the Civil Rights movement in Newark differed from other movements in the North.

According to the Report of The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known better as the Kerner Commission or Kerner Report, the Civil Rights movement can be separated into major stages: the Colonial Period, Civil War and “Emancipation”, Reconstruction, the Early 20th Century, World War I, the Great Depression and New Deal, World War II, and the focus of this paper, the postwar period (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 95-106). During the war, Black Americans waged what was known as the “Double-V Campaign”: victory against foreign enemies and fascism abroad, and victory against racial discrimination at home (Mumford, 2007, p. 32). After having experienced racially integrated life and interracial relationships while being deployed in Europe, specifically England and Germany, during the Second World War, Black veterans came home with a renewed vision for racial equality in the United States. Kevin Mumford, author of Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America, describes this sentiment among Black Americans well, explaining that,“‘…before [Black American Soldiers] go out on foreign fields to fight the Hitlers of our day, [they] must get rid of all Hitlers around us,’’ (Mumford, 2007, p. 36). This renewed sense of conviction for equal rights combined with a World War II emphasis on liberty and personal freedoms (although not intended for Black Americans), antithetical to fascist governments of Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, formed the ideological groundwork for a culture of Black Americans ready to relentlessly pursue equal and just treatment during the postwar period.

The postwar period began with grassroots movements in the South, most prominently the Alabama bus boycotts which led to the meteoric rise of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., who for many White Americans (on opposite sides of the spectrum of racial tolerance), served as the unofficial spokesman of the Civil Rights movement (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 106). While other Civil Rights leaders such as Malcolm X were prevalent within the movement, Martin Luther King Jr.’s message of nonviolent resistance meant less disruption in the lives of White Americans, and thus garnered more support from that group. As the Civil Rights movement gained traction, not just in the south but across the entire United States, elected officials were pressured to create legislation that would address the core agenda of the Civil Rights movement. One key example is the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed employment discrimination against “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin,” under Title VII (Sugrue, 2008, p. 360-1). The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark victory for Civil Rights groups in both the North and South, as it not only ended certain measures of discrimination, but provided the first steps towards “equality” of Black Americans.

This legal measure acted as the first step away from legal discrimination for Black Americans, but as legal barriers began to lift, social and corporate barriers quickly took their place. The definition of racism changed drastically during this period. According to Carol Anderson, author of White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide, “…[when] Confronted with civil rights headlines, depicting unflattering portrayals of KKK rallies and jackbooted sheriffs, white authority transformed those damning images of white supremacy into the sole definition of racism,” which in turn, caused more hostility between White and Black Americans, as Black Americans continued to fight for societal equality and justice (Anderson, 2017, p. 100). As racism became harder to prove on a legal basis, methods of resisting racism became more extreme. The transition from legal to societal discrimination marked a shift in the Civil Rights movement, with the justification of violence rising amongst many different Civil Rights groups and characterizing Northern protests from Southern.

Newark

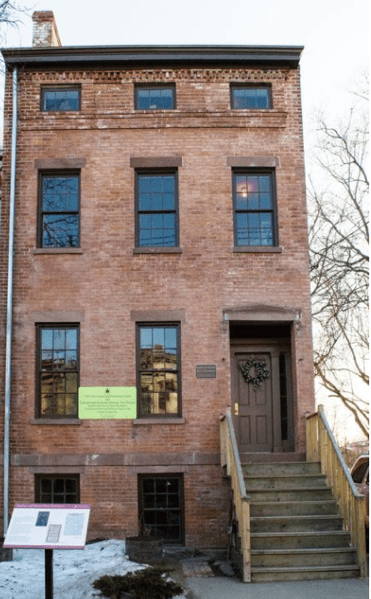

Newark is a port city in New Jersey founded in 1666, by the Puritan colonists who claimed the land after removing the Hackensack Native American tribe against their will. Like the Black Americans who would come to occupy the city, the Hackensack natives would be largely removed from the narrative surrounding Newark’s development (Mumford, 2007, p. 13). Newark possessed a strong Black community for much of its history, yet this community existed outside of the White public sphere. This Black community published their own newspapers, participated in their own ceremonies, and formed their own societies, creating a distinct circle separate from the White population (Mumford, 2007, p. 17). Throughout many periods of the long Civil Rights movement, White citizens of Newark vigorously resisted Black American integration in their city, maintaining societal segregation (Mumford, 2007, p. 18). In 1883, the City of Newark passed legislation prohibiting segregation in hotels, restaurants, and transportation, yet what could have been sweeping and unprecedented reform of 19th century civil rights policy was ultimately undermined when consecutive policies for equal protection and education were blatantly disregarded by White Newarkers (Mumford, 2007, p. 19). The culture of Jim Crow was alive and well in a city that saw neighborhoods of many different demographics tightly compacted next to each other (Mumford, 2007, p. 22).

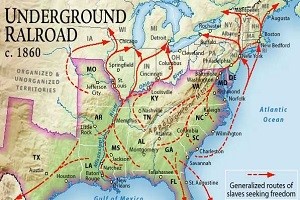

The Great Migration period also affected Newark’s Black public sphere, with Black Southerners migrating to northern cities in hopes for a better life (Mumford, 2007, p. 20). At the same time, Newark experienced an influx of European immigrants from countries such as Italy and Poland. The relationship between Italian Americans and the Black community worsened during the Great Depression, as both groups were affected by diminishing opportunities in manufacturing jobs, a relationship that would only continue to curdle into the 1950s and 1960s (Mumford, 2007, p. 27). This relationship was only further exacerbated by Italians taking up positions of authority in public housing projects that housed mostly black tenants and families (Mumford, 2007, p. 58). The Great Migration, which resulted in 1.2 million Southerners heading North due to World War I labor shortages, was emphasized by ambitious recruitment and enthusiasm for a new place (Mumford, 2007, p. 20). According to demographer Lieberson and Wilkinson, the migrating Black Southerners did find some success in the economic opportunities of the North, with an inconsequential difference between the incomes of Black native Northerners and themselves (Lieberson & Wilkinson, 1976, p. 209). Overall, northern cities offered blacks economic opportunities unavailable in much of the South—indeed many migrated to northern cities during and after World War I and World War II when employers faced a shortage of workers. Overall, however, blacks were confined to what one observer called “the meanest and dirtiest jobs,” (Sugrue, 2008, p. 12).

Integration continued to spread throughout the Central Ward of Newark (otherwise known as the heart of the city, and predominantly black), and into the South, West, and North Wards, with the North Wards containing a large Italian migrant population (Mumford, 2007, p.

62). By 1961, the Civil Rights movement officially entered Newark, with the Freedom Riders, Civil Rights activists from the South, congregating in Newark’s Military Park before continuing their journey to other Southern states (Mumford, 2007, p. 78). Tensions between Italians and Black Americans came to a head in 1967, when an unqualified Italian “crony”, rather than an already appointed capable Black candidate, was appointed by the mayor for a public school board position at a school in which half the students were black. The conflict arising from this situation would eventually become one of the reasons for the 1967 Newark riots (Mumford, 2007, p. 104).

Newark Riots of 1967

The inciting incident of the Newark riots was the arrest and subsequent beating of cab driver John William Smith at the hands of White police officers (Mumford, 2007, p. 98). According to those living in apartments that face the Fourth Precinct Station House, they were able to see Smith being dragged in through the precinct doors. As recounted in the Kerner Commission, “Within a few minutes, at least two civil rights leaders received calls from a hysterical woman declaring a cab driver was being beaten by the police. When one of the persons at the station notified the cab company of Smith’s arrest, cab drivers all over the city began learning of it over their cab radios,” (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 33). After the police refused to negotiate with civil rights leaders representing a mob that formed outside, the crowd was dispersed by force, and reports of looting came in not long after. The Newark riots had begun, and they would end up being the most destructive race riot among the forty riots that occurred since Watts two years earlier (Reeves, 1967). The violence, looting, and firebombing became so severe that units of both State Police and National Guardsmen were sent into the Central Ward to lay siege to the city (Bergesen, 1982, p. 265). According to newspaper articles written about the riots, “Scores of Negroes were taken into custody, although the police said that 75 had been arrested…the injured in the hundreds…more than 100 persons had been treated [in hospital] alone,” (Carroll, 1967). Additionally, “A physician at Newark City Hospital said four persons had been admitted there with gunshot wounds…stabbed or struck by rocks, bottles, and bricks,” (Carroll, 1967). Four people were shot by Police for looting and six Black Newarkers died as a result of police officers and National Guardsmen firing into crowds, showcasing that police violence during the Newark riots was indiscriminate, racially charged, and often fatal (Bergeson, 1982, p. 265). The initiating events in Newark would spread to other major urban centers in New Jersey in the week following the riots, with varying degrees of severity.

Understanding the history of Newark, the inciting events of these riots, and the progress of these riots is key to uncovering Newark’s and, in a broader sense, New Jersey’s role in the Civil Rights movement. This paper analyzes how violence is used as a distinction between riots in the North and South. It also investigates the main causes of the Civil Rights movement and subsequent rioting in Newark, including the phenomenon of “White flight,” redlining and the housing crisis, and poverty caused by rapid urbanization. Lastly, the paper considers the impact of the lack of public welfare programs, intercommunity-autonomy and governmental transparency as tools for curbing civil unrest amongst majority black communities.

Lasting Effects on the City of Newark

Twenty-six people died during the Newark riots, most of whom were Black residents of the city, and over 700 people were injured or hospitalized during the riots. The property damage resulting from the looting and fires valued at over ten million dollars, and spaces still exist where buildings once stood (Rojas & Atkinson, 2017). The long-term physical and psychological effects of the riots on the people of Newark and on the reputation of the city itself cannot be understated (Rojas & Atkinson, 2017). Beyond the pain and grief caused by the loss of life and property, the riots represented a paradigm shift for Newark as a city. The eruptive violence in the city streets was perhaps the final nail in the coffin arranged by systemic racism, as Newark’s reputation as a dangerous city plagued by violence and corruption solidified in the minds of its former White residents and White generations long after (Rojas & Atkinson, 2017). As a result, the entrenched Black communities of Newark found themselves losing tax revenue and job opportunities quickly. The disadvantages that came from the riots and their causes only further incentivized White families to keep their tax dollars and children as far away from Newark as possible; this also occurred during a time in which taxes for police, fire, and medical services were being increased to compensate emergency departments for their involvement in the riots (Treadwell, 1992). Areas such as Springfield Avenue, once a highly commercialized street, were turned into abandoned, boarded up-buildings, further contributing to Newark’s negative reputation (Treadwell, 1992). What once were public housing projects, well lived-in homes, and family businesses remain vacant and crumbling, if not already demolished from the looting and fires fifty years ago which much of Newark did not rebuild (Treadwell, 1992). Even church buildings which once conveyed a sense of openness to all of the public are lined with fences and barbed-wire to prevent looting and vandalism (Treadwell, 1992). While the riots did lead to Black and Latino Americans vying for political positions that previously belonged to the White population, ushering in the election of the first Black mayor and first Black city council members in Newark in 1970 (Treadwell, 1992). Despite Black Americans gaining some control politically, the Central Ward still lacked economic and social renewal, with any efforts towards regenerating Newark failing to undo the larger effects of the riots of 1967 (Treadwell, 1992). Any of the limited economic development that did occur was largely restricted to “White areas”, such as downtown Newark, as opposed to the Black communities (“50 Years Later,” 2017). Larry Hamm, appointed to the Board of Education at 17 years old by Newark’s first Black mayor, expounds on the economic disparity between Black and White Newarkers, with “dynamism [prevalent] downtown, and poverty in the neighborhoods,” (Hampson, 2017). Fifty years after the riots, police brutality remains a constant for Black Newarkers, with a 2016 investigation into the Newark police department finding that officers were still making illegal and illegitimate arrests, often using excessive force and retaliatory actions against the Black population (“50 Years Later,” 2017). A city with a large Black population, one third of Newark residents remain below the poverty line, with Newark residents only representing one fifth of the city’s jobs (Hampson, 2017). Despite the foothold that Black Americans have gained in Newark’s politics, the economic power largely remains in the hands of White corporations and organizations (Hampson, 2017). Other economic factors, such as increases in the cost of insurance due to increased property risk, tax increases for increased police and fire protection, and businesses and job opportunities either closing or moving to different (Whiter) neighborhoods following White flight also have a significant lasting economic impact on the city (“How the 1960s’ Riots Hurt African-Americans,” 2004). The people of Newark were also affected psychologically and emotionally. On one hand, many Black Americans felt empowered – their community had risen against injustice and was largely successful in catching the nation’s attention despite the lack of real organization, challenging the system that desperately tried to keep them isolated and creating a movement that emphasized their power (“Outcomes and Impacts – the North,” 2021). Yet, just as many Black Americans became hopeless, seeing a country and its law enforcement continue to disregard their lives and stability, treating them as secondary citizens despite the many legal changes made under the guise of creating equality (CBS New York, 2020).

The riots of 1967 destroyed Newark’s reputation and economic stability, steeping the population in poverty. While the Black Community used this opportunity to gain political power in the city and to jumpstart the Black Power movement in New Jersey, many Black Newarkers remain in despair, seeing their community members injured and killed with no change to the systemic cycle of racism that perpetuates the city.

The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders Report (Kerner Commission Report)

The 1968 National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders Report is one of the most referenced resources in this paper, due to the unique document’s origins, in which sitting President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967 tasked a commission specifically with determining the causes of the rising number of U.S. race riots that had occured that summer, with the riots in Detroit and Newark acting as catalysts for the founding of the commission. While Johnson essentially anticipated a report that would serve to legitimize his Great Society policies, the Kerner Report would come to be one of the most candid and progressive examinations of how public policy affected Black Americans’ lives (Wills, 2020). The Commission was led by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, and consisted of ten other men, most of whom were White. The only non-white members of the Commission were Roy Wilkins, an NAACP head, and Sen. Edward Brooke, a Republican from Massachusetts (Bates, 2018). Despite the lack of racial representation on the commission, the members placed themselves in the segregated and redlined Black communities they were writing about, interviewing ordinary Black Americans and relaying their struggles with a humanistic clarity that was largely uncharacteristic of federal politics in the 1960s. This report identified rampant and blatant racism as the cause of the race riots of 1967, starkly departing from Lyndon B. Johnson’s views on race relations and in the process establishing historical legitimacy as a well-supported and largely objective source (Haberman, 2020). The Kerner Commission clearly outlines how segregation, White Flight and police brutality contributed the most to worsening race relations and rising tensions between Black communities and the White municipal governments who mandated said communities (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 119, 120, 160). Despite the Kerner Commission clearly outlining the causes and effects of the racial climate of the 1960s, the commission makes no effort to justify the riots themselves, or even validate the emotions and frustrations resulting from the oppression that the Commission identifies. For everything that the commission does state, it leaves just as much unstated. As the Commission explains, America in the 1960s was in the process of dividing into two separate, unequal, and increasingly racially ubiquitous societies, and the Commission itself validates this theory by displaying a clear identification of what the Black experience looks like while having next to no willingness to justify or defend the riots themselves (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 225). The Kerner Commission is a factually accurate but contextually apathetic document which, for its purpose in this paper, serves as one of the key documents due to its accuracy; yet it is important to acknowledge its shortcomings in the larger context of the Civil Rights Movement. Despite clearly identifying both the causes of the 1967 race riots and racial tensions in America, the Kerner Commission has gone largely ignored, as many of the issues identified by the commission remain present in Black communities, and in some instances, have worsened significantly, such as the issues of income inequality and rising incarceration rates (Wilson, 2018).

Section 1: How Newark and the Northern Civil Rights Movement was Alike and Consistent with Civil Rights Movements in the South

Newark’s riots and Civil Rights movement reflected many of the same characteristics seen in Civil Right movements across the country, both in the North and South. Key similarities between Newark and the rest of the Civil Rights movements in the United States, as well as decisive factors that sparked the rioting in Newark, include the phenomenon of “White Flight”, effects from police brutality and over-policing as a result of White Flight, and the quickly deteriorating relationship between black communities and law enforcement with the introduction of the National Guard into areas of conflict, combined with the familiar effects of redlining that are still visible across the United States today.

White Flight

One of the main causes of the Newark riots was the phenomenon known as “White flight”, and the effects caused by extreme racial isolation. To truly understand the impacts of “White Flight”, one must first define the concept. “White Flight” is the unique phenomenon of middle class White Americans leaving cities that were becoming more diversely integrated with Black Americans who were migrating from rural areas to these cities. In the 1950s, 45.5 million White Americans lived in areas considered to be “cities”, yet research by Thomas Sugrue in his work Sweet Land of Liberty explains how although the White population in cities did increase in the next decade, it was not of the same rate as previous years or in line with the Nation’s whole white population, with theoretically 4.9 million White Americans leaving cities between 1960 and 1965 (Sugrue, 2008, ch. 7, Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 119). American cities were becoming less white, caused by Black American populations in cities increasing, and resulting in an even greater Black population in urban centers (Sugrue, 2008, p. 259). This population movement was not only seen in the South or key cities in the North such as Detroit and Chicago (though present there as well). Kevin Mumford explains Newark’s experience with this phenomenon, citing how the Central Ward of Newark (i.e., the “heart” of the city) included 90 percent of the black population of Newark, a drastic difference from the initial years of the Great Migration which saw only 30 percent of Newark’s black population settling in the Central Ward (Mumford, 2007, p. 23). White flight changed the landscape of New Jersey, with densely populated cities such as Newark, Trenton, and Camden becoming more clearly divided from new suburban residential areas, and the development of these new suburban areas leading thousands to flee the inner cities (Mumford, 2007, p. 50).

White flight impacted more than just the distinct and divided racial makeup of cities and suburbs; impacts were also seen in other areas of life. The “persistant racial segregation” in post-war America often decided what kind of education an individual received, what jobs were accessible, and even the quality of an individual’s life (Sugrue, 2008, p. 201). Urban (i.e., majority Black) residents were further hurt from this White flight, as suburban areas located close to urban centers drained urban areas of their taxes, decreased their population, and left fewer jobs available to urban communities (Sugrue, 2008, p. 206). The lack of urban taxes funding urban public schools resulted in unequal educational opportunities, further validating the White argument that having Black Americans in cities “ …signified disorder and failure” (Mumford, 2007, p. 5).

What ultimately made White Flight possible and cyclically reinforced White privilege was agency. White Americans possessed the agency to choose home ownership, involved and “cookie-cutter” communities, and access to adequate education. They had stronger and better-funded education systems, public services, and largely avoided many of the social problems that plagued black communities, including economic instability, lack of reliable housing, and health issues further exacerbated by overcrowded living conditions. Furthermore, White Americans did not fear the police, as this form of law enforcement showed an extensive history of protecting and benefitting White communities. As explained by Sugrue,”Ultimately, the problem of housing segregation was one of political and economic power, of coercion, not choice, personal attitudes, or personal morality,” (Sugrue, 2008, p. 249). The existence of a black middle class and integrated suburbs represented a deterioration of this agency, and was therefore not permitted by the larger White population. The considerable and ever growing gap of wealth, stature, and control between White and Black Americans was not lost on the Black urban population. After being revitalized by the hope that the World War II emphasis on freedom and liberty gave Black Americans, the disappointment and bitterness that stemmed from the lack of social change morphed public opinion in Black communities from that of optimism to resentment (Sugrue, 2008, p. 257). This resentment, exacerbated by continuous outside stressors, would eventually bubble over into violent demonstrations. The hundreds of racial revolts of the 1960s [The Newark riots among them] marked a major turning point in the black revolution, highlighting the demand for African American self-determination (Woodard, 2003, p. 289).

White Flight was a fundamental motivator in the Newark riots, yet was experienced by urban centers across the North, South, Midwest, and West Coast. The stark contrast between Black and White Americans in regards to agency over housing, public programs, education and law enforcement, stemming from the upending of White Americans’ tax dollars from urban centers grew dramatically and inversely during the 1950s and 1960s, setting the stage for a period of unprecedented violence and racial unrest in America’s cities. Post-war optimism among Black Americans was severely dashed by the lack of extension of freedom and liberty at home, and the financial and social atrophy that followed would inform fierce resentment among Black Americans, ushering in a newer, more embittered chapter of the Civil Rights movement.

Police Brutality, “Snipers”, and the National Guard

As American cities became increasingly Black due to the phenomenon of White flight, already strained relationships between Black Americans and law enforcement worsened. Newark saw a palpable shift in intercommunity relations with the police. Over-policing and police brutality in Black neighborhoods acted as a product of a lack of racial representation in the ranks of American police forces (Bigart, 1968). To further emphasize this divide between the police and minority groups, the use of brute force was prevalent on the Black population, especially during the riots of the late 1960s. Police brutality against John William Smith acted as an inciting event to the Newark riots, but brazen, and often fatal violence at the hands of Newark’s police forces fanned the flames of violent unrest.

Even before the Newark riots, the police were infiltrating and undermining Civil Rights groups in America’s cities. One such case that preceded the riots occurred in the suburb of East Orange, New Jersey, in which multiple Black Muslims were arrested, resulting in the arrestees being released from jail having sustained a fragmented skull, lacerations, and genital trauma at the hands of the police (Mumford, 2007, p. 110). This incident occurred only a week before the Newark riots, and is, in hindsight, indicative of the Newark Police Department’s willingness to enact acts of brutal violence in the name of “keeping the peace” and disrupting leftist organizations (Mumford, 2007, p. 110). As chronicled by Sugrue, the Black population of America,”…doesn’t see anything but the dogs and hoses. It’s all the white cop,” (Sugrue, 2008, p. 329).

The Newark riots began, fittingly, at a police station. After John William Smith was allegedly beaten by two white officers and brutalized in holding, a mob formed in front of the Fourth Precinct demanding to see the taxi driver and his condition. Any hopes of the crowd being dispersed peacefully and a riot being avoided were dashed when a Molotov cocktail struck the police station (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 33). The ensuing riot control would prove more destructive and archaic than the looting and arson being committed at the hands of rioters. Riot police, armed with automatic rifles and carbines, fired indiscriminately into the air, at cars, at residential buildings, and into empty storefronts of pro-black businesses (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 38). At least four looters were shot and at least six civilians were killed as a result of firing into crowds (Bergesen, 1982, p. 264-5). Beyond gun violence, a specific instance in which a black off-duty police officer attempting to enter his precinct during the riots was beaten and brutalized by his white coworkers who did not recognize him offers an indication of how unprompted much of the violence against the Black population of Newark was (Carroll, 1967). In the end, 26 people died, and over 69 were injured (Carroll, 1967).

As extreme as the violence against demonstrators was during the Newark riots, it was far from unique. Similarly tactless and lethal methods of crowd control had been deployed during race riots in Watts and Detroit (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 20, 54). Another similarity between these three race riots, as well as other race riots in the South, were the supposedly looming presence of urban snipers (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 180). While it remains unseen if Black nationalists armed with sniper rifles were truly as ubiquitous as the media would have then made it seem, what is verifiable is the fact that Riot Police used urban snipers as justification to scale up militarization efforts and enter and proliferate Black communities (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 40, Mumford, 2007, p. 142). Despite being difficult to verify, the threat of snipers waiting patiently to pick off police officers in dense urban areas was a deeply vivid and real threat to police and National Guardsmen sent into Newark and other cities. In Newark, there are multiple accounts of police firing indiscriminately into apartment windows out of fear for snipers. It is assumed, however, that most reports of sniper fire during race riots across cities in the United States were misidentified shots sourced from police or National Guardsmen (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 180).

The presence of the National Guard as peacekeepers during the Newark riots is another factor that is both consistent with other race riots and contributed heavily to high death tolls among said race riots. Of the roughly 17,000 enlisted New Jersey National Guardsmen that responded to the riots in 1967, only 303 of them were Black (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 37). The largely white Guardsmen who were tasked with keeping the peace in cities in the full swing of anarchy had for the most part only had limited experience with black people, let alone crowd control operations. The majority of the reporting Guardsmen at Newark were young, not adequately psychologically or tactically prepared, and “trigger happy” (Bigart, 1968). The naivety of these Guardsmen, the presence of military-grade equipment such as machine guns and armored vehicles, and the looming threat of snipers created a situation in which it is possible that black demonstrators were seen as an enemy force to be subdued or neutralized, rather than American citizens engaging in protest. By any measure, however, the temperament of the National Guard displayed a clear and fervent prejudice against African Americans, and Guardsmen were reported to have taken part in the destruction of Black lives and property alongside Newark Police and New Jersey State Police (Bigart, 1968). Reinforcing a clear bias against Black Americans, Black enlistment in the National Guard declined deeply following integration within the Guard. There is no way of knowing for sure if a higher number of enlisted black Guardsmen would have led to a deeper understanding of Black communities, and in turn a less destructive response to the race riots of the 1960s; yet the police brutality that faced John William Smith, and the subsequent brutality that faced Newark rioters further exacerbated the riots themselves, with police using the word “sniper” as an excuse to wreak havoc on the Black masses.

Redlining and the Turn from Legal to Public Discrimination

Redlining is a discriminatory practice in which Black citizens were segregated into specific neighborhoods under the guise of lacking financial assistance through loans and government programs, rather than Jim Crow Laws. Large areas of residential housing occupied disproportionately by Black homeowners were designated to be high-risk by banking organizations, and would thus be denied housing loans to move out of their neighborhood. The results of this practice were strictly segregated neighborhoods that existed far beyond the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and ostensibly dashed any possibility for Black Americans to build generational wealth. Redlining is a key example of how many discrimination practices, in both the North and South, changed from being legally enforced to publicly and socially enforced. Redlining and public discrimination practices affected Black communities in both the Northern and Southern United States, and contributed directly to the Newark riots by preventing Black Americans from accruing generational wealth, pushing out “ghetto” communities through urban renewal, and forcing Black Americans to remain in impoverished communities through publicly enforced racial lines.

Redlining was conceptualized and implemented during the Second World War, when William Levitt revolutionized residential communities with easily built and affordable housing in the form of Levittown, America’s first true suburb. Initially, Levitt, a staunch segregationist, outright banned Black Americans from living in his communities on the basis of race. As a result, Black Americans paid more on average for housing than White Americans did, while being excluded from access to new and contemporary housing (Sugrue, 2008, p. 200). As advancements in legal protections for Black Americans were made during the 1950’s, realtors, leasing managers and landlords shifted their efforts towards a more privatized form of discrimination, emphasizing the individual rights of businesses to decide who to do business with (Sugrue, 2008, p. 202). White Americans in the North during this time had developed a curious sense of superiority over the discriminatory culture and customs of the South, despite engaging in the same discriminatory practices under the guise of “Freedom of Association,” (Sugrue, 2008, p. 202). White Americans in the north drew their own lines, publicly enforcing White-only neighborhoods and refusing Black consumers access to their housing market, similar to the Jim Crow laws in the South. At the same time that White liberals were expressing admiration for Dr. Martin Luther King, they were drawing invisible borders through their communities, ready and willing to relegate Black Americans to ghettos if it meant their property value remained high (Mumford, 2007, p. 65). Black Americans not only faced discriminatory lending practices, as a single black family had the potential to shutter a community of well-to-do-whites, but in addition the Federal Housing Administration was in open support of restrictive covenants (Sugrue, 2008, p. 204).

For Black Americans, it was not only enough to prove that they could exist in white neighborhoods without presenting a risk to White financial assets and housing, it was their responsibility to justify their existence in White suburbs against the risk of financial loss. As Sugrue explains, “It was one thing to challenge the status quo; it was another to create viable alternatives,” and black communities were not able to create these alternatives while still effectively being segregated (Sugrue, 2008, p. 220). As a result of these discriminatory practices, Black Americans’ experiences with White Americans was primarily relegated to that of interactions with the police. Redlining only served to further solidify many Black communities as “ghettos”, as many areas that became heavily redlined were already suffering from unemployment and disinvestment. Furthermore, redlined communities were subject to urban renewal efforts, where black communities were essentially uprooted to make room for expanding public projects that were intended to displace the ghetto population (Theoharis & Woodard, 2003, p. 291). A specific example of this phenomenon would be the “Medical School Crisis”, a major catalyst for the Newark riots in which a school campus was proposed that would displace Black citizens in Newark’s Central Ward (Theoharis & Woodard, 2003, p. 291).

The effects of redlining in Black neighborhoods was severe. The extent of the widening wealth gap was not lost on Black Americans, who truly began to feel the effects of a lack of self-governance and generational wealth, both of which could not exist inside redlined communities. Black Americans became further aware not only of the wealth gap, but in the differences in status and power that existed between Black and White Americans (Sugrue, 2008, p. 257). Economic inequality became synonymous with racial inequality, and Black Americans began actively protesting both as a result of redlining (Sugrue, 2012, p. 10). As previously mentioned, urban development was a rising trend amongst metropolitan areas, and the superhighways needed to make the newly paved American Highway system work often involved building massive ramps and tracts of highway over residential housing that could not be sold (Sugrue, 2008, p. 259). Public school systems were affected as well. As previously recounted in the effects of White flight, taxes were being drained from urban centers to fund schools bordering between central cities and White suburbs, yet Black Americans did not benefit from these schools, remaining segregated and without necessary resources to make their education truly “equal” (Sugrue, 2008, p. 206). Gerrymandering further ensured these separate school districts, drawing more invisible lines that dictated which schools children living in certain areas would attend (Sugrue, 2012, p. 13). Many White community members argued that these schools were not separated intentionally, but that it was “… the natural consequence of individual choices about where to live and where to send children to school,” completely disregarding that the segregated districts are a byproduct of White-imposed redlining (Sugrue, 2012, p. 14). The effects of this practice were so dire that Newark’s mayor called for the state control of public schools (Bigart, 1968). In the end, the image many White Americans held of Black neighborhoods became a self-fulfilling prophecy; that redlined areas were occupied by gangsters, bootleggers, and other criminals. In reality, the economic hardships imposed by stringent redlining created the circumstances under which crime was inevitable (Sugrue, 2008, p. 203).

Beyond a network of financial discrimination, the White general public also maintained the lines surrounding redlined communities through publicly and socially enforced separation. Rare cases of Black families attempting to move into segregated majority White neighborhoods such as Levittown were almost always met with at best, verbal, and at worst, physical abuse (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 119). To Whites, the impoverished neighborhoods of Newark were no better than “…a vast crawl of negro slums and poverty, a festering center of diseases, vice injustice, and crime,” (Mumford, 2007, p. 52) and the acceptance of Black families into White neighborhoods represented a direct threat that their communities would be labeled the same way.

Redlining and the practice of socially and publicly enforcing discrimination measures affected Black communities across America, and contributed directly to the riots by preventing Black Americans from leaving the poverty-stricken neighborhoods known as “ghettos”, forcing urban renewal on the already limited spaces Black Americans could live, and furthering the wealth gap between Black and White Americans. Redlining proved to be a long-lasting roadblock in the slow march towards the advancement of America’s Black Population. Its inception and widespread use was indicative of a still-segregationist White America who was willing to explore alternative avenues in the name of maintaining the racial purity of their neighborhoods. Redlining essentially served as the next interpretation of Jim Crow laws – severe stratification of Black economies, reinforced by a White majority committed to keeping said system in place (Mumford, 2007, p. 22). In response to these measures, Black groups that were not against using violence to enact results began to popularize, leading to an expansion of the Black public sphere, the establishment of the Black Power movements, and the rise in riots across the country.

Section 2: How Newark and the Northern Civil Rights Movement Differed from the…

Civil Rights Movement of the South

Despite their significant similarities, the Northern and Southern Civil Rights movement differ in various ways that allow for specific characteristics of each movement. The greatest difference between the two regional movements was the ideas and theories surrounding the use of, and different applications of, violence as a means for social change. As the South turned towards nonviolent measures of civil protest, the North did the opposite, at times using the South as an example of how nonviolent protests were not successful (Sugrue, 2008, p. 291). After experiencing the nonviolent tactics of the South and observing the little change it brought to the North, people in Newark and other cities in the North began to use more aggressive tactics, such as firebombs, molotovs, and violent protests, both as aggressors and defenders.

The South and Nonviolence

In the years leading up to the Newark riots, attention was once again on the South as nonviolent ideology continued to spread and characterize the Southern Civil Rights movement.

Nonviolent protests stemmed out of Selma, Alabama, when Civil Rights workers staged a protest in 1965, law enforcement interrupted the protest, and weeks later two White supporters of the Civil Rights movement were killed by racists due to their participation (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 20). Other indicators of the Southern ideology of the Civil Rights movement are further exemplified by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a Civil Rights organization which used protest measures such as sit-ins, boycotts, and the Freedom Rides, and whose headquarters was located in Atlanta (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 29). When the Freedom Riders arrived in Newark in 1961 on their way to Tennessee, the Black community of Newark saw firsthand how nonviolent protesting in the South functioned (Mumford, 2007, p. 78). Newark would experience many other nonviolent Civil Rights events before the riots of 1967, including the events of Freedom Summer 1964, which acted as a campaign to recruit Black voters, and the actions of the Congress of Racial Equality (at this point a civil disobedience organization that would later join the Black Power movement) who organized sit-ins at White Castle diners across New Jersey for better treatment of Black consumers and just hiring protocols for aspiring Black employees (Mumford, 2007, p. 80). Violence against Black Americans continued despite these protests, including the death of Lester Long Jr. and Walter Mathis, which further reminded the

Black community of one of the most notorious lynchings, Emmett Till (Mumford, 2007, p. 117).

It was clear to many Black Northerners that racism, discrimination, and brutality against Black Americans would not bend to nonviolent will, therefore causing the Northern Civil Rights movement, and, by extension, the Newark rioters, to use more aggressive tactics in order to stimulate change.

Violence and Resistance in Newark and the North

Black Americans in Newark and across the North bore witness to the nonviolent protests in areas such as Birmingham and Selma, and, instead of imitating their methods, used these events as justification for turning to more violent tactics (Sugrue, 2008, p. 291). Nonviolent protesting measures were criticized by many, including key individuals such as Nathan Wright, an author prevalent in the Black Power movement, who claimed that it lowered “black self-esteem” and led to the ideology that Black community members themselves were not worth defending (Mumford, 2007, p. 111). To many Black Americans, violence was a justifiable means, aligning with the psychoanalytic theory of Frantz Fanon, who claimed that “…the development of violence among the colonized people will be proportionate to the violence exercised by the threatened colonial regime,” (Mumford, 2007, p. 109). Up to this stage in the Civil Rights movement, and for decades after, the effect of White colonialism, segregation, brutality, redlining, and other discriminatory measures more than sufficed as violence exercised against the Black American people, and therefore provided the North and the rioters of Newark with a justifiable means to turn towards violence.

The Northern Civil Rights riots themselves were steeped in aggressive tactics, though it is uncertain in many circumstances whether the rioters were the true initiators of such events. Molotovs and firebombs became key components of the movement, mostly the threat rather than the use themselves. Police confiscated six bottles with the makings of Molotov cocktails after raiding the homes of various Black Americans who were classified as “militant”, and Black activists anonymously dispersed guides on how to assemble these incendiary weapons (Mumford, 2007, p. 115, Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 22). During the Newark riots, fires spread through downtown Newark, yet officials from the Fire Department adamantly claimed that the rioters were not the ones who set the fire (Carroll, 1967). There were also reports of gunfire between law enforcement and Black rioters, with the gunfire being “aimed” at police reportedly originating from the tops of buildings and the interiors of cars, further exacerbating the rumors of “snipers” attacking the police and National Guard (Carroll, 1967).

Other riots in the North experienced severe aggression as well, though with substantial evidence that some rioters were instigators in the events. In the Plainfield riots, a series of New Jersey riots that mirrored those of Newark, black youths were reported physically assaulting and murdering a police officer, Gleason, to which the police department then claimed that “…under the circumstances and in the atmosphere that prevailed at that moment, any police officer, black or white, would have been killed…” in the hostile situation (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 44). This, black rioters recognized, would be used as a justification for retaliation against all Black rioters. Rioters (the majority young) then began arming themselves with carbines from a local arms manufacturing company, and firing without clear targets (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 45). This is a drastic change from the nonviolent protests that characterized the South, and furthered the distinction between the Northern Civil Rights and Southern Civil Rights movements. Though the changes between the protesting tactics of the North and South remain markedly different, there remain many differences between Northern protests as well, including the roles that welfare and public programs, intercommunity agency, and governmental transparency play in maintaining peace.

Section 3: How Various Civil Rights Movements in the North Differed from Newark and Each Other

Anti-Poverty and Welfare Programs

Anti-Poverty and welfare programs proved to be invaluable tools for New Jersey’s cities in diffusing racial violence before it escalated to the level of the Newark riots. In New Brunswick, following the events in Newark, a growingly despondent group of Black youths began committing what the Kerner Commission refers to as “random vandalism” and “mischief” (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 46). Despite being relatively harmless, concerns still loomed that an eruption of violence comparable with Newark remained a possibility in New Brunswick. As a result, the city government funded a summer program for the city’s anti-poverty agency (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 46). Enough young people signed up for leadership positions in the summer program that the city cut their stipends in half and hired twice as many young people (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 46). This summer program did not single-handedly deescalate racial tensions between Black youth and White city government, but it did establish a rapport that was utilized to come to a sort of common ground (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 46). The same cannot be said about the events that transpired in Plainfield, around the same time. Like New Brunswick, Plainfield was on the brink of extreme racial violence, and in similar fashion, young people and teenagers were demanding community recreation activities be expanded. The city government, however, refused, and Plainfield went on to sustain violence and destruction at the hands of rioters, second only to the Newark riots (Mumford, 2007, p. 107).

Perhaps it seems overly simplistic to suggest the difference between neighborhood kids and radicalized arsonists is simply having something to do; but what is repeatedly noted by the Kerner Commission in their profile of an average Newark rioter is a lack of preoccupation. They describe the typical rioter as young, male, unmarried, uneducated and often unemployed (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 73). These men often did not attend high school or university, and went into and out of periods of joblessness. What is noteworthy is that the attitude of these men towards education and employment is that of frustration, rather than apathy (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 78). According to the Commission Report, rioters typically desired more consistent and gainful employment or the opportunity to pursue a higher education, but were stymied by race or class barriers (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 78). The Kerner Report established a pattern of explaining systemic barriers to positive social, health, economic, and education outcomes, quickly followed by assertions of black pathology. The report does not conclude that it is absolutely logical to find oppression intolerable and that some type of action should be expected, or an apathy toward political and educational systems would be a rational response to these barriers (Bentley-Edwards et. al., 2018). Regardless, there appears to be a direct correlation between giving urban youths leadership positions within their communities, and a desire to preserve and protect that community. Perhaps if this tactic was employed by the city of Newark, there would have been less desire to loot and proliferate, and more importantly, the possibility that this tactic could be used in contemporary urban centers.

Communal Autonomy and Self-Governance

As mentioned earlier in this paper, a sense of communal agency was paramount in upholding White privilege, and was a consistently desired standard in New Jersey’s cities during the 1960s. In Elizabeth, an impending race riot was preemptively undone by utilizing intercommunity autonomy and self-governance (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 40). Among a hundred volunteer peacekeepers in Elizabeth was Hesham Jaaber, an orthodox Muslim leader who led two dozen of his followers into the streets, armed with a bullhorn to urge peace and order (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 40). Both demonstrators and police dissipated and a full riot failed to materialize in Elizabeth (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 40). This approach can be compared with the Newark riots, in which peace was supposed to be achieved at the hands of nearly 8,000 heavily armed, excessively violent White National Guardsmen who knew nothing about the people they were supposedly deployed to serve. Per the example in New Brunswick, a correlation between the effectiveness of de-escalation measures from law enforcement who live in that community and the ineffectiveness of de-escalation in cities when law enforcement do not reside in that community becomes apparent.

Government Transparency and Community-Government Partnerships

An excellent example of how government transparency can positively affect race relations is the previous example of New Brunswick. Despite the success of the anti-poverty summer program, there still remained a radical sect of incensed young people in the city. When this group of 35 teenagers expressed an interest in speaking directly to the newly instated Mayor Sheehan, the Mayor obliged their request and agreed to meet with them (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 46). After a long discussion in which the teenagers “poured their hearts out,” Sheehan agreed to draw up plans to address the social ills that these young Black Americans were facing. In return, the 35 young people began sending radio broadcasts to other young people, insisting that they “cool it,” and emphasized the Mayor’s willingness to tackle Black issues (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 46). Sheehan also demonstrated her willingness for peaceful negotiation with her constituents when in the days after the Newark riots, a mob materialized on the steps of city hall, demanding that all those jailed during demonstrations in New Brunswick that day be released from holding. Rather than using the police to disperse the group by force, Sheehan met the mob face to face with a bullhorn and informed them that all held arrestees had already been released. Upon hearing this, the mob willingly dispersed and returned home (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 47).

It is perhaps unsurprising that the Newark police did not utilize these tactics, though they had ample opportunities to do so. In the moments directly before the riot, in front of the Fourth Precinct Station House, Mayor Addonizio and Police Director Spina repeatedly ignored attempts by Civil Rights leader Robert Curvin to appease the crowd by performing a visual inspection of John William Smith for injuries (Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968, p. 117). It was not until nearly a full day of rioting had occurred before Mayor Addonizio even considered a political solution to the rioters demands, and by that point it was too late to reach an arrangement (Mumford, 2007, p. 129).

The consistent factor among instances of avoided and deescalated violence is a level of mutual respect between city government officials and Black communities. Repeatedly, arson, looting, and destruction of property occurred in areas where rioters felt that their surroundings, their infrastructure, and community did not belong to them. Based on evidence mentioned in this section, it is clear that the more a community is involved in administering the area that they live in, the more they feel inclined to defend and preserve their neighborhood.

Conclusions and Why Teaching This History is Necessary

This paper analyzed key distinctions between inciting events of the Civil Rights movement riots in the North and South, including the differing ideologies on nonviolent verses violent protesting, the phenomenon of “White flight” and subsequent redlining, the housing crisis and poverty caused by rapid urbanization and lack of public welfare programs. This paper explains how intercommunity autonomy and government transparency, along with anti-poverty measures were underutilized tools in curbing civil unrest amongst Black communities, leading to increased tensions, anger, and distrust between Black Americans and White communities and government. It also compares the violence prevalent in Northern Civil Rights movement protests, stemming from disregard and denial of the blatant systemic racism rampant in the states, to the nonviolent protesting measures characteristic of the South and the Civil Rights movement as a whole. Throughout the recapitulation of the Civil Rights movement, specifically that in New Jersey using the Newark Riots of 1967, a side of state history that is often overlooked becomes clearer. Through this clarification, one can see the effects this history still has on New Jersey, and, in a larger sense, the United States today. As students continue to see protests regarding the injustice, inequality, and brutality facing Black communities in New Jersey and across the country, the importance of understanding the decisions throughout history that sparked these events becomes all the more important. Without understanding “White flight”, students cannot fully understand why center cities have a vast majority Black population, while suburbs remain significantly White. Without understanding redlining in key cities such as Newark, students cannot understand why New Jersey schools severely lack diversity, still remaining severely separated, or why tax money from central cities are being redirected to schools bordering suburbs.

Without understanding the deep history of police brutality toward Black Americans, students cannot fully understand or analyze the tragedies of today, such as the death of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Elijah Jovan McClain, and countless others. Racism and discrimination is deeply rooted not only in the South, not only in the North, but in New Jersey and the entirety of America, and the effects of such racism and discrimination are still seen daily. It is impossible to separate the history of New Jersey from its racist roots, making understanding these roots integral to understanding New Jersey. Now more than ever, teachers are forced to critically think about what role the history of racism in America has in their classroom – yet the conversation must exist with students for as long as the effects of this racist past are still seen in classrooms across the United States, including their home state. By centering the education of racism on New Jersey, students make a deeper connection to the history, and recognize that racism and segregation, as often taught in history classes, did not solely exist in the South, but down the street from them, in their capital, and across the “civilized” North. Teachers can use Newark as a way to initiate the conversation of racism in New Jersey, educating students on how racist institutions and injustices evolved into rioting, how the cycle is still seen today, and how many of the reasons people in 1967 rioted are still reasons that they saw people riot in 2020. When teaching about the Civil Rights movement, teachers can include the North in their instruction, emphasizing how racism looked different in the North compared to the South, yet still perpetuated inequality. It is not a happy history, nor one that citizens should be proud of- and it is far from being rectified. Yet, it is the duty of citizens and students of New Jersey to research these topics that are often overlooked and hidden, to analyze how racism and discrimination still impacts Black New Jersians, before analyzing the post-war Civil Rights movement and the activism and movements such as Black Lives Matter in New Jersey today. By failing to educate students on the effects of racism in the North, students are left uneducated on how to identify legal and institutionalized racism, and vulnerable to misinformation. Until the measures of deeply ingrained racism and discrimination are fully dissolved and racial injustice is consistently upended, beginning with proper education, protesting and civil unrest will remain a constant in the American experience, as will the consistent need to educate students on these injustices.

References

Primary Sources:

“50 Years Later, Newark Riots Recall an Era Echoed by Black Lives Matter.” (2017). NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/50-years-later-newark-riots-recall-era-echoed-black-lives-n780856.

Bates, K. G. (2018). “Report Updates Landmark 1968 Racism Study, Finds More Poverty and Segregation.” NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/02/27/589351779/report-updates-landmark-1968-racism-studyfinds-more-poverty-more-segregation.

Bigart, H. (1968) “Newark Riot Panel Calls Police Action ‘Excessive’; Newark Riot Panel Charges Police Action against Negroes Was ‘Excessive’.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/02/11/91220255.html?page Number=1.

Carroll, M. (1967). “Newark’s Mayor Calls in Guard as Riots Spread.” New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/07/14/83616047.html?page Number=1.

CBS New York. (2020). “Newark Public Officials Reflect on 1967 Riots amidst New Protests: ‘The City Has Now Begun to Rise from the Ashes’.” CBS New York. CBS New York. Retrieved from https://newyork.cbslocal.com/2020/06/01/newark-riots-1967-protests/.

Haberman, C. (2020). “The 1968 Kerner Commission Report Still Echoes Across America.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/us/kerner-commission-report.html.

Hampson, R. (2017). “Newark Riots, 50 Years Later.” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/07/12/50-years-after-newark-trump-urban-america-inner-city-detroit/103525154/.

Handler, M. S. (1967). (“Newark Rioting Assailed by Meeting of N.A.A.C.P.; N.A.A.C.P. Hits Newark Riots.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/07/16/83617963.html?page Number=1.

“How the 1960s’ Riots Hurt African-Americans.” (2004). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/digest/sep04/how-1960s-riots-hurt-african-americans.

“Outcomes and Impacts – the North.” (2021). RiseUp North Newark. Retrieved from https://riseupnewark.com/chapters/chapter-3/part-2/outcomes-and-impacts/.

Reeves, R. (1967). “Riots in Newark Are the Worst in Nation since 34 Died in Watts.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/07/15/83617474.html?page Number=11.

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. (1968). Bantam Books. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat03997a&AN=RUL.b115507 2&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Robinson, D. (1967) “Jersey Will Seek U.S. Funds to Rebuild Newark; Riot Victims Would Get Food, Medicine, Business Loans and Money for Rent.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/07/18/90375693.html?page Number=22.

Rojas, R., & Atkinson, K. (2017). “Five Days of Unrest That Shaped, and Haunted, Newark.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/11/nyregion/newark-riots-50-years.html.

Special, H. B. (1967). “Newark Riot Deaths at 21 as Negro Sniping Widens.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1967/07/16/archives/newark-riot-deaths-at-21-as-negro-s niping-widens-hughes-may-seek-us.html?searchResultPosition=26.

Sullivan, R. (1968). “Negro Is Killed in Trenton.” New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/04/10/89130687.pdf?pdf_redirect =true&ip=0.

Treadwell, D. (1992). “After the Riots: The Search for Answers : For Blighted Newark, Effects of Rioting in 1967 Still Remain : Redevelopment: The Once-Bustling Commercial Thoroughfare at the Center of That City’s Unrest Is Still an Urban Wasteland 25 Years Later.” Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-05-07-mn-2525-story.html.

Waggoner, W. H. (1967). “Courtrooms Calm as Trials Start for 27 Indicted in Newark Riots.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/09/26/83634623.html?page Number=41.

Wills, M. (2020). “The Kerner Commission Report on White Racism, 50 Years on …” JSTOR Daily. Retrieved from https://daily-jstor-org.ezproxy.usach.cl/the-kerner-commission-report-on-white-racism-50 -years-on/.

Wilson, B. L. (2018). “The Kerner Commission Report 50 Years Later.” GW Today. Retrieved from https://gwtoday.gwu.edu/kerner-commission-report-50-years-later.

Secondary Sources:

Anderson, C. (2017). White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (1st ed.). Bloomsbury, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Bentley-Edwards, K. L., Edwards, M. C., Spence, C.N., Darity Jr., W. A., Hamilton, D., & Perez, D. (2018). “How Does It Feel to Be a Problem? The Missing Kerner Commission Report.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the SocialSciences 4, no. 6: 20–40. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2018.4.6.02.

Bergesen, A. (1982). “Race Riots of 1967: An Analysis of Police Violence in Detroit and Newark.” Journal of Black Studies 12, no. 3 (March 1, 1982): 261–74. Retrieved from https://search-ebscohost-com.rider.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN= edsjsr.2784247&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Lieberson, S., and Wilkinson, C. A. (1976). “A Comparison between Northern and Southern Blacks Residing in the North.” Demography 13, no. 2: 199–224. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060801.

Mumford, K. J. (2007). Newark : A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America. American History and Culture. New York University Press. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat03997a&AN=RUL.b140884 3&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Sugrue, T. J. (2012). “Northern Lights: The Black Freedom Struggle Outside the South.” OAH Magazine of History 26, no. 1: 9–15. doi:10.1093/oahmag/oar052.

Sugrue, T. J. (2008). Sweet Land of Liberty : The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North. 1st ed. Random House. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat03997a&AN=RUL.b140557

6&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Theoharis, J., & Woodard, K. (2003). Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940-1980. 1st ed. Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat03997a&AN=RUL.b1327086&site=eds-live&scope=site.