Curriculum on “The Arab-Israeli Conflict”

By Chloe Daikh

Chloe Daikh was a volunteer at a refugee camp in Palestine, served as an AmeriCorps VISTA College Access & Success Coordinator, and taught at a boarding school in Virginia. Following this article is the Institute for Curriculum Services (ICS) description of the grade 6-12 lessons and links to its resources. The package for “Teaching the History of the Arab-Israeli Conflict” includes lesson plans, a slide deck, learning objectives, essential questions for students to address, primary sources, and links to recommended videos (https://icsresources.org/curriculum/the-arab-israeli-conflict/). Some of the ICS documents are included along with comments on the article and the ICS curriculum by local teachers.

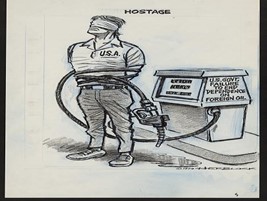

Since Hamas’s attack on October 7, 2023, there has been an increased interest in helping K-12 students understand the historical background and context of the current violence in Israel/Palestine that has now escalated to a war in Lebanon and the possibility of a regional war involving Syria, Yemen, and Iran. On October 20, 2023, The Office of the Texas Governor encouraged schools to use a list of resources shared by the Texas Education Agency “to increase awareness and understanding of the Israel-Hamas war and root causes of conflict in the region” (Office of the Texas Governor, Greg Abbott, 2023). First in a list of four resources hyperlinked to the press release is a document from the Institute of Curriculum Studies (ICS) titled “Support for Classroom Discussion on the Hamas-Israel War,” which in turn includes a link to ICS’s curriculum, “Teaching the History of the Arab-Israeli Conflict Using Primary Sources.”

The Institute for Curriculum Services (ICS) is not new to teacher training. Founded in 2005, their website states that 18,000 teachers have engaged in their workshops, and that all 50 states and D.C. are represented within ICS’s pool of participants. The reach of ICS’s influence in secondary school instruction is further facilitated through cooperation with the National Council of Social Studies and many of their state affiliates and local districts, including New York Department of Education; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction; Iowa Department of Education, among many others (ICS, 2024). ICS published its “Teaching the History of the Arab Israeli Conflict Using Primary Sources” in 2022 and has promoted the curriculum as an effective tool for teachers to help students understand the history of the conflict. In addition to the curriculum, which is accessible for free online and includes worksheets and graphic organizers for students (2022a), ICS offers workshops, both online and in-person in collaboration with public school districts across the country (2024). However, key aspects of ICS’s curriculum are misaligned with standards for the study of history and geography and are not conducive to helping students understand the root causes of Hamas’s attack on October 7, 2023, nor Israel’s widely condemned response. This curriculum, by providing students with insufficient context and inaccurate information, primes students to uncritically condone and support Israel’s ongoing settler colonial violence and dispossession, and contributes to the dissemination of racist, Islamophobic tropes.

Misalignment with C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards

By using standard curriculum formatting and creating materials and activities that can be easily implemented for class instruction, ICS’s curriculum looks like a credible curriculum, and thus may seem like a legitimate tool for teaching about Israel/Palestine. ICS claims that their curriculum is “guided by, and…in alignment with, state and national standards” (ICS, 2018b). The organization points to the Frameworks in the C3 Framework for Social Studies as supposed guiding principles for the creation of their curricular resources, “with a particular focus on Dimension 2: History and “Dimension 3: Evaluating Sources and Using Evidence” (ICS, 2018b).The National Council for the Social Studies states that the C3 Framework was developed “for states to upgrade their state social studies standards” and “for practitioners…to strengthen their social studies programs” (2013). ICS claims to specifically and particularly align with two Dimensions within the framework: “History” and “Evaluating Sources and Using Evidence” (ICS 2018b). While ICS does not claim to address “Geography,” its substantial use of (political) maps requires attention to the desired learning outcomes of that Dimension as well. An analysis of the ICS curriculum compared to the learning outcomes outlined in the C3 Framework demonstrates the curriculum’s failure to meet standards for social studies education. This article will highlight specific ways in which the ICS curriculum is misaligned with the C3 Framework’s learning outcomes, and will include resources that, had they been included in the curriculum, would meet the expressed skills standards and learning outcomes. The C3 Framework includes learning outcomes which are used as a basis of the critique of ICS’s curriculum.

| C3 Framework Learning Outcomes (achieved by end of Grade 12) (National Council for Social Studies, 2013, pp. 42-49) Dimension 1: History Change, Continuity, and Context “Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.” Perspectives “Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during historical eras.” “Analyze how historical contexts shaped and continue to shape people’s perspectives.” Historical Sources and Evidence “Analyze the relationship between historical sources and the secondary interpretations made from them.” “Critique the usefulness of historical sources for a specific historical inquiry based on their maker, date, place or origin, intended audience, and purpose” “Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.” “Critique the appropriateness of the historical sources used in a secondary interpretation.” Causation and Argumentation “Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.” “Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.” “Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past” “Critique the central argument in secondary works of history on related topics in multiple media in terms of their historical accuracy.” Dimension 2: Geography Human-Environment Interaction “Evaluate how political and economic decisions through time have influenced cultural and environmental characteristics of various places and regions.” Evaluate the impact of human settlement activities on the environmental and cultural characteristics of specific places and regions.” Human Population “Evaluate the impact of economic activities and political decisions on spatial patterns within and among urban, suburban, and rural regions.” Dimension 3: Evaluating Sources & Using Evidence Gathering and Evaluating Sources “Gather relevant information from multiple sources representing a wide range of views while using the origin, authority, structure, context, and corroborative value of the source to guide the selection.” |

ICS’s selection and framing of primary source material is misaligned with several learning outcomes outlined within the C3 Framework’s Dimension 2: History. ICS limits the sources provided to official governmental and intragovernmental documents and fails to provide citations for the background information that frames each of the sources and provides the overarching narrative of the curriculum. In this way, ICS fails to provide students with the opportunity to adequately strengthen skills pertaining to the study of history. Furthermore, through their narrow selection of sources, ICS fails to model the effective evaluation of sources and use of evidence for students, as outlined in Dimension 3 of the C3 Framework.

Through its failure to adequately address skills mandates as outlined in the C3 Framework, ICS dangerously misrepresents the historical context and multiple perspectives that are necessary for helping students understand the context of Hamas’s October 7 attack. In order for ICS to meet those standards, it would need to include significantly more primary sources and provide more accurate context. The ICS curriculum implies that Zionist settlers accepted Palestinians as deserving of national sovereignty in their own right and that it was solely Palestinians who rejected Jewish neighbors, beginning with the UN Partition Plan of 1947 (ICS, 2018a). The curriculum emphasizes this implication by providing inaccurate and incomplete information, insufficient, misleading and oversimplified context, and a single perspective of events. Furthermore, it is not grounded in the skills or learning outcomes outlined within the C3 framework, to which ICS claims to adhere.

Inaccurate & Incomplete Information

ICS provides inaccurate and incomplete information within the curriculum, particularly when it comes to the perspectives and experiences of Palestinians. Two serious issues that contribute to this lack of accurate and complete information are the lack of Palestinian-authored sources. Only one source written by a Palestinian is included in the entire curriculum–the Declaration of the State of Palestine (1988), in the final lesson (2022f). The Palestinians are only represented in the curriculum long after decades of representing themselves under the British Mandate. In this way, the designers of the ICS curriculum de-historicize and choose to frame Palestinian “nationalist aspirations” in a document that is comparable to the Israeli Declaration of Independence included in Lesson 4 (2022e). This factually inaccurate portrayal of the inception of the First Intifada misrepresents the most important aspects of the Intifada; namely, that it was a largely nonviolent series of protests and economic boycotts of Israel that were predominantly organized by women, eventually involved the support of Israeli peace organizations and was as much of a surprise to the PLO as it was to the Israeli occupation (Bacha, 2017).

To address the lack of Palestinian perspectives within the curriculum, primary sources that deal with the Palestinian experience of the Nakba should be included to provide an insight into the Palestinian perspective of the 1948 war, particularly given that the Nakba is widely viewed as ongoing to the present day in the context of continued settlement expansion. The Nakba Archive (2002) is a collection of oral history testimony from Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon and provides valuable context for both the Declaration of the Establishment of Israel document and the Arab League Declaration on the Invasion of Palestine, which is the second primary source included in ICS’s Lesson 4 (2022e). Additional incorporation of photographs or videos from the UNRWA Film & Photo Archive, which provides audio and visual documentation of Palestinian refugees since 1948 would provide additional insight into the lived experience of Palestinians during the Nakba and counter the lack of visual representation of Palestinians within the curriculum (UNRWA, 2016).

The inclusion of a wider variety of primary sources such as film, photographs, and posters would provide students with a more accurate representation of the First Intifada and would align with the C3 Framework’s stated learning outcomes. It would also provide insight into the rise of more violent tactics employed by Palestinians since the Second Intifada that would better contextualize the Hamas attack on October 7. ICS states, in framing the First Intifada at the beginning of Lesson 5, that “Palestinians attacked Israelis with improvised weapons and firearms supplied by the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), which organized much of the uprising” (2022f). This factually inaccurate portrayal of the inception of the First Intifada misrepresents the most important aspects of the Intifada. By inaccurately portraying the First Intifada, ICS legitimizes Israel’s violent response to the uprising and lacks context that would help students understand the cause-and-effect relationship between Israeli military and settler violence and the use of violent tactics by some members and groups of the Palestinian resistance.

Lack of Context

Building on the issues that stem from the lack of accurate and complete information, the lack of sufficient context further strengthens ICS’s implication that Palestinians have only been antagonistic aggressors to Israel and their Jewish neighbors. In Lesson 1 of the curriculum (2022b), the excerpt from Theodor Herzl’s “The Jewish State” (1896) lacks contextualization regarding the existing Palestinian population and their historical ties to the land ignoring the settler colonial nature of Zionism and its impact on the indigenous population of Palestine (ICS, 2022b). In Lesson 3, there is a major gap in source material from May 1948 to June 1967 (ICS, 2022d). This gap leads to a total lack of context for the inception of the 1967 war, as well as the experience of Palestinians in the years between 1948 and 1967. This lack of context makes it impossible for students to investigate Palestinian perspectives and understand cause-and-effect relationships between historical events.

The excerpt from “The Jewish State” highlights Herzl’s concerns about antisemitism across Europe, proposing the establishment of a Jewish state as a solution. The document reflects the persecution faced by Jews in Europe and their quest for a sovereign homeland. However, the document lacks contextualization regarding the existing Palestinian population and their historical ties to the land ignoring the settler colonial nature of Zionism and its impact on the indigenous population of Palestine (see Table 1 2a & 6a). It also omits Herzl’s recognition of the need for support from the Great Powers for the successful establishment of a Jewish state.

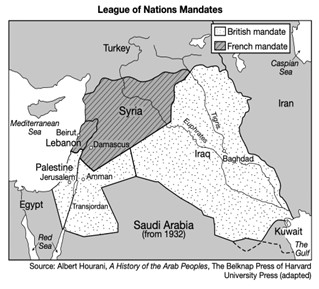

The gap in source material and information on events that occurred between May 14/15, 1948 and the June 1967 war conveys an inaccurate and incomplete depiction of the experience of Palestinians in the months and years after the creation of the state of Israel. This erasure functions in service of the curriculum’s portrayal of Palestinians as exclusively antagonistic and unwilling participants in peacebuilding. Of course, the entirety of “The Jewish State” (Herzl, 1896) is too long of a document to present to 6th-12th grade students, the target audience of ICS’s curriculum; however, the excerpt excludes text that highlights important context for the document (see Table 1 2b & 3d). An aspect of early Zionism that is also apparent in Herzl’s text but excluded from ICS’s excerpt is that multiple locations were considered for the Jewish state. Herzl highlights Palestine and Argentina (Argentine in the text). The selection of Palestine or Argentina for the Jewish state would be left to the Powers and Jewish consensus, “we shall take what is given us, and what is selected by Jewish public opinion” (American Zionist Emergency Council, 1946). Herzl mentions “the present possessors of the land” in reference to either or both Palestinians and Argentinians already living in areas proposed for the Jewish state, demonstrating his awareness that there were people living in both areas prior to Zionist colonization. By adding a few sentences to the excerpt, ICS could better contextualize the document regarding the existing Palestinian population, the settler colonial nature of Zionism, and the role of European imperialism’s support for the foundation of the Jewish state. Palestinian nationalism shifted away from “Arab/Ottoman” to “Palestinian/Arab” in the context of “watershed events” that included the British control of Palestine and the Balfour Declaration (Khalidi, 1997/2010). The ICS curriculum frames nationalism as only legitimately developing pre-World War I, which severely misrepresents the historical contexts in which Palestinian nationalism developed (see 1a, 4a & 4b). Herzl expresses the need for Great Power intervention for the Zionist project to be reified: “Should the Powers declare themselves willing to admit our sovereignty over a neutral piece of land, then the [Jewish] Society will enter into negotiations for the possession of this land” (American Zionist Emergency Council, 1946). Herzl further elaborates on the necessity of Great Power subscription to the Zionist project, “The Society of Jews… [will put] itself under the protectorate of the European Powers.” Herzl’s document demonstrates an amenability to the colonial mandate system that eventually came into effect after the ratification of the Covenant of the League of Nations in 1922.

Another useful addition to the collection of primary sources that would provide much-needed context for the time during May 1948 and June 1967 are the UN General Assembly Resolution 194 (1948) and UN Security Council Resolution 242 (1967). UN General Assembly Resolution 194 Article III (1948) codifies the right of return for Palestinian refugees who wish “to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors” and “that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property.” UN Resolution Security Council 242 (1967) of the “withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict,” i.e. the 1967 war. and reaffirms the importance of “a just settlement of the refugee problem.” The Israeli unwillingness to honor this right of return coupled with the continuous expansion of settlements since 1967 and continued occupation of the West Bank (and Golan Heights) are major obstacles to peace that are completely ignored by the ICS curriculum.

Single Perspective

The ICS curriculum privileges Great Power perspectives, from which Zionism as a political project was birthed, without providing sufficient information on their imperial context. This serves to legitimize the Great Power intervention in the region beginning after World War I, and the expansion of Israeli settlements since 1967, without providing sufficient information to nuance or question this perspective.

By relying heavily on primary source documents that advance only the Great Power colonial perspective such as the Balfour Declaration, Sykes-Picot Agreement, and Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, ICS’s curriculum presents the colonial project and interventions advanced by the authors of these documents as legitimate, without giving students the resources or information to question the right or authority of the Great Powers to undermine the sovereignty of people living within the region following the end of World War I. This legitimization of the Great Power’s imperial project in the region after World War I contributes to the portrayal of Palestinians as antagonistic and unwilling to work towards a peaceful resolution to the conflict.

Additionally, the curriculum developers’ decision to use only political maps (themselves crafted by ICS) that do not align with internationally recognized borders and disputed territories, rather than demographic and land use maps, fail to provide information that is essential to understanding Palestinians’ perspectives. ICS’s curriculum completely ignores the expansion of settlements in the West Bank, confiscation of land, demolition of homes, and displacement of civilians, avoiding any discussion of numerous UN resolutions and United States foreign policy over time. By depicting political boundaries that have resulted from military occupation as if they were incontrovertible facts, the maps erase the issue of territorial annexations that have not been recognized under international law. The illegal settlements in the West Bank are legitimized in the video at the beginning of Lesson 4 (ICS, 2019). They are described as “in locations chosen for their strategic security value,” though there is no explanation of what that “value” might be. The video further states that “the number of settlements remained sparse until the late 1970s. They would become a major issue in later negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians.” The illegal settlements and settlement expansion are not mentioned again in the curriculum, despite the fact that settlement expansion and settler violence, along with the right of return for Palestinian refugees, are two of the primary concerns in negotiations with Israelis. Furthermore, settlements have been deemed illegal in successive judgements in institutions of international law, human rights and justice (Amnesty International, 2019).

A primary source that would provide useful insight into the perspectives of people living within Palestine contemporaneous with the other sources included by ICS is the Resolution of the General Syrian Congress at Damascus, which was ratified on July 2, 1919. The congress was composed of members from all regions of Ottoman Greater Syria who described themselves as “provided with credentials and authorizations by the inhabitants of our various districts, Moslems, Christians, and Jews” (1919). The resolution provides important insight into how Arab nationalism was shifting as a result of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Of the ten points included in the resolution, five include important context for several of the primary sources included in ICS’s curriculum, namely the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Covenant of the League of Nations, the British Mandate for Palestine, the Balfour Declaration, and the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement. Point three is a protest against Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations; the Congress unanimously rejected the institution of a mandate. Point six addresses the issue of Zionism. It states, “We oppose the pretensions of the Zionists to create a Jewish commonwealth in the southern part of Syria, known as Palestine” and that “our Jewish compatriots shall enjoy our common rights and assume the common responsibilities.” The Congress was not opposed to the millennia-long presence of Jewish people in the land of Greater Syria, but soundly opposed to the Zionist settler colonial project, an important distinction left out of the ICS curriculum. Point eight of the resolution rejects the separation of Greater Syria into Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, as was outlined in the Sykes-Picot agreement. Finally, point ten calls for the annulment of “these conventions and agreements” whose aim is establishment of a Zionist state in Palestine in light of “President Wilson’s condemnation of secret treaties,” seemingly a direct response to both the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Balfour Declaration.

The inclusion of demographic and land-use maps would provide needed information to contextualize Palestinian resistance, particularly to settlement expansion since 1967. Alex McDonald of the Texas Coalition for Human Rights, in a video lesson titled “Letting Maps Tell the Story” (2020), is a valuable resource for educators seeking to help students employ geographic studies skills to examine the geopolitical context of the conflict. Additionally, the inclusion of UN Resolution 2334 (2016) would provide useful information on the ways in which Israel’s settlement expansion continues to make a two-state solution unviable. This would provide students valuable information on the Palestinian perspectives of Israel’s policy of expansion, and additional context for discussing causes and effects. The ICS curriculum developers chose to use only politically contested maps, rather than the very demographic and land use maps that would illuminate the situation under the Mandate before 1948, and which indeed formed the basis for the UN Partition Plan. For the period after 1948, land use, demographic information, and water resource maps would better align with the C3 Framework and provide context for discussing causes and effects.

Conclusion

Not only is the curriculum misaligned with standards for skill development in history and social studies, but it also fails in its expressed objectives. The stated goal of ICS’s curriculum, entitled “Teaching the Arab-Israeli Conflict” is that “students will become more knowledgeable global citizens and gain confidence in following current world issues” (2022a). Under the FAQ section of the ICS website, under the drop-down menu titled “What is ICS’s commitment to accuracy and balance?” the organization states that “accuracy is a value in itself. At a time when public discourse in America is becoming less committed to accuracy and facts, we think it is all the more important that we study historical documents and ground our understanding of history in them” (2018b). ICS’s curriculum, by providing students with insufficient context and inaccurate information across all five lessons, primes students to uncritically condone and support Israel’s ongoing settler colonial violence and dispossession rather than helping them become “more informed global citizens” (2022a). It fails to meet both its own professed goals and standards for social studies education and skills acquisition. This curriculum prevents students from engaging with the full historical context of the current situation and implicitly claims that the exclusion and erasure of Palestinian voices is an acceptable form of “accuracy.”

References

American Zionist Emergency Council. (1946). Texts Concerning Zionism: “The Jewish

State” by Theodor Herzl (1896). Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/quot-the-jewish-state-quot-theodor-herzl.

Amnesty International. Chapter 3: Israeli Settlements and International Law. (2019,

January 30). Amnesty Retrieved on November 14, 2024 from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2019/01/chapter-3-israeli-settlements-and-international-law/.

Archive. (2002). Nakba Archive. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://www.nakba-archive.org/#.

Bacha, J. (Director). (2017, November 12). Naila and the Uprising [Film]. JustVision. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://justvision.org/nailaandtheuprising.

General Syrian Congress (1919 July 2). The resolution of the General Syrian Congress at Damascus proclaims Arab sovereignty over greater Syria (July 2, 1919). In A.F. Khater (Ed.), Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, 2nd edition (2011) (pp. 158-160). Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2018a, June 4). ICS Episode 3: A place to belong. Vimeo. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://vimeo.com/273382658.

Institute for Curriculum Services (2018b, June 27). About Us. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://icsresources.org/about-us/#faqs.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2019, September 9). ICS Episode 4: War and Peace. Vimeo. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://vimeo.com/358927133.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2022a, February 23). Teaching the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://icsresources.org/curriculum/the-arab-israeli-conflict/.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2022b, February 23). Lesson 1: Zionism and Arab Nationalism. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://icsresources.org/wp-content/uploads/ICS_Lesson1_Zionism.pdf.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2022c, February 23). Lesson 2: Broken Promises.

Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://icsresources.org/wp-content/uploads/ICS_Lesson2_BrokenPromises.pdf.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2022d, February 23). Lesson 3: The British Mandate

Era. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://icsresources.org/wp-content/uploads/ICS_Lesson3_The-Mandate.pdf.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2022e, February 23). Lesson 4: From 1948 to the

Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://icsresources.org/wp-content/uploads/ICS_Lesson4_1948to1979.pdf.

Institute for Curriculum Services. (2022f, February 23). Lesson 5: The Continuing Arab-

Israeli Conflict & Peace Process. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://icsresources.org/wp-content/uploads/ICS_Lesson5_ContinuingConflict.pdf.

Responses to Chloe Daikh and the ICS Curriculum

Given the often-contentious nature of the subject discussed in the article above, editors for Teaching Social Studies solicited comments from teachers and preservice educators. Those responses are below.

Alysse Ginsburg, Uniondale (NY) High School: I am a 12th grade history teacher with 25 years of classroom teaching experience. The editors asked me to respond to this essay in 250-500 words. Of course, I can’t possibly respond thoughtfully or comprehensively to a 5,000 word essay in the allotted space, but I do have a few thoughts to share. Prior to reading the essay, I had not used ICS materials in my classroom. A colleague with experience using them had good things to say, so I investigated further. As a history teacher, I believe it is important to carefully examine the sources of content I might bring into my classroom to be sure they are accurate and align with standards and best practices. Here are a few things I concluded about ICS’s lessons:

- The lessons on the Arab-Israeli conflict align well with both the New York Social Studies Framework and New Jersey’s Learning Standards for Social Studies (which are similar to the C3 Framework).

- ICS’s lessons rely on primary sources representing different parties. For example, in the lesson on Jewish and Arab nationalism, I noticed the inclusion of primary sources from a mainstream Zionist thinker and a mainstream Arab nationalist thinker and documents from both the first Zionist Congress and the first Arab Congress. The number of sources provided seemed balanced and appropriate for the available time a teacher would have to teach the lesson.

- ICS has been around for almost 20 years and has professional development partners in many state and local education agencies; 21,000 teachers have elected to participate in ICS programs; and ICS is a Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Consortium Member.

I was honestly reluctant to submit this response without knowing even more, so I had a call with ICS and asked them to address some of the author’s comments directly. In addition to patiently answering my questions, they said they looked forward to seeing the essay (and even speaking to the writer) so they could understand her concerns and consider improvements, as they often do with teacher input. For example, they told me that they recently updated one of their PD sessions to further clarify the specific reasons why Palestinians and Arabs were opposed to the United Nations Partition plan. I’m an educator who believes in a growth mindset, so this pleased me. Though I had very limited space and time to respond to the essay, I was impressed by what I saw and heard from ICS, and I encourage you to look at their lessons and materials and judge for yourself. My main critique, which I told them, was that they should modify their materials for students at different reading levels. They said they were working on it.

Dianne Pari, former social studies chair, Floral Park (NY) High School: As an educator with experience as a social studies teacher, department chairperson, and currently a supervisor of student teachers, I have observed a growing hesitation among today’s teachers to address the Arab-Israeli conflict in the classroom. Many shy away from student questions about the current situation. Why? There are many complex reasons, but it cannot be overlooked that in today’s politically charged climate, even the most neutral or fact-based responses can be misconstrued, criticized, or politicized. There have been cases where educators have faced backlash from parents and school administrations simply for presenting information that challenges students’ or families’ existing beliefs or biases.

This makes it imperative that curriculum materials on this topic are balanced, historically accurate, and free of bias. I support Chloe Daikh’s assertion that the ICS curriculum on “The Arab-Israeli Conflict” lacks this balance, particularly in its limited inclusion of Palestinian voices and perspectives. Such omissions can unintentionally perpetuate a one-sided narrative, portraying Palestinians predominantly as aggressors and Israelis solely as defenders for example. The Daikh article provides a detailed evaluation of the ICS curriculum, and I agree with her conclusions. Unfortunately, she, nor the ISC, touch upon the issue I raised earlier, that teaching the Arab-Israeli Conflict is so polarizing today, that it is often being avoided altogether.

If I were teaching this topic today, I would begin with two foundational lessons to establish historical context, especially of previous conflicts, and then transition to an analysis of the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. To ensure a broad and balanced understanding, I would incorporate a range of news sources, including major American outlets and international media such as Al Jazeera that offer valuable resources for classroom discussion. Online, Al Jazeera provides “Israel-Gaza War in Maps and Charts: Live Tracker” (https://www.aljazeera.com/news/longform/2023/10/9/israel-hamas-war-in-maps-and-charts-live-tracker).

Students must be provided with balanced, credible, and comprehensive resources that foster critical thinking and informed discussion—especially when addressing complex and emotionally charged global issues such as this one and more importantly, teachers must be supported by school administrators when their lessons are challenged.

John Staudt, The Wheatly School, East Williston, NY: As a teacher and a historian, I largely agree with Chole Daihk’s analysis of the Institute for Curriculum Services (ICS) curriculum on “The Arab-Israeli Conflict.” There are several significant methodological and historiographical shortcomings, including biases that teachers should explore with students when teaching controversial topics.

The ICS prioritizes using state-centric sources while overlooking everyday experiences of the people most impacted by the actions of state characters. It leaves out numerous critical primary sources – most egregiously – from Palestinian voices and perspectives. The exclusive inclusion of mostly official documents is a prime example of what the scholar Edward Said called “textual imperialism.” Textual imperialism is a form of revisionist history written from the perspectives of the victors, while overshadowing the personal experiences of those who lost and suffered the most. (Said, 1993) By excluding Palestinian literature before the 1988 Declaration, the ICS distorts the history of Palestinian nationalism and erases decades of Arab political activism.

The exclusion of nineteen-years of actions, words and events between 1948 to 1967, reveals a broad gap in the literature and obscures crucial historical information including, among other things, evolution of early resistance movements, the formation of Palestinian political consciousness and the fate of Palestinian refugees. These omissions inevitably distort historically crucial links and obscures important continuities underlying present-day controversies and conflicts. These significant oversights also distort the First Intifada as PLO-initiated violence which minimizes its original non-violent, civic nature.

The geographic mapping options Daikh makes note of demonstrate significant bias. By incorporating political maps that legitimize military occupation, the curriculum normalizes settlements that are recognized as illegal under international law. When coupled with the absence of sources featuring Palestinian perspectives this further exacerbates the historical revisionism in the curriculum. By excluding alternative demographic and land-use maps, students do not grasp the circumstances — displacement, resource distribution, fragmentation — underlying Palestinian perspectives and reasons for resistance.

The ICC’s narrative makes Palestinian activism appear violently aggressive, while misinterpreting Israeli policy as almost entirely defensive. A good example of the problem is the exclusion of Israeli historian Ilan Pappé’s “1948 paradigm.” Pappe challenges the mainstream Israeli narrative of the 1948 war as a struggle for independence, instead arguing it was a deliberate campaign of ethnic cleansing to expel and displace Palestinians — a perspective he claims has been suppressed in historical discourse. The ICC approach further obscures the structural, settler-colonialism of the Israeli-Arab conflict (Pappé, 2006). I think it is significant to mention that Pappé was born in Israel after the 1948 war and is a Jew whose parents fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Pappé teaches in Great Britain after he was pressured to resign his position at the University of Haifa because of his confrontational views of official Israeli government policies.

As teachers, our goal is to provide students with a range of materials to analyze so they can reach conclusions based on evidence and share with colleagues in respectful conversations. By utilizing selected sources focusing on mostly one perspective of this deeply complicated issue, the ICC’s approach reenforces historical and geographical biases and does a disservice to students and the general public who are interested in learning more about this and other controversial topics. To counter these tendencies, historians and social studies teachers must employ meticulous attention to detail and incorporate perspectives that challenge an educator’s own arguments instead of following preordained interpretive templates.

Erin Smyth, Social Studies Education Student, Hofstra University: As a graduate student pursuing a degree in secondary social studies education, I was asked to review the Institute for Curriculum Services (ICS) curriculum on the Arab-Israeli conflict alongside Chloe Daikh’s critique of it. On the whole, I agree with Daikh’s analysis. The ICS curriculum fails to provide a complete historical account of the conflict. It leaves out essential historical events and excludes sources from individuals, particularly Palestinians, directly affected by the conflict. This omission hinders students from developing a nuanced understanding of a complex historical issue.

My biggest issue with the ICS curriculum is the absence of Palestinian-authored sources. Aside from the one late inclusion in the curriculum which Daikh notes, the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence, there are no primary sources that focus on Palestinian perspectives, even though the curriculum repeatedly includes Zionist and Israeli sources. This imbalance results in a distorted narrative which is evident in the way the Nakba is covered. The curriculum gives little attention to the mass displacement of Palestinians in 1948 and omits oral histories, failing to convey how the Nakba is experienced by generations of Palestinians. As a result, students are denied the opportunity to understand one of the long-lasting impacts of the conflict on Palestinians.

These omissions not only negatively impact students’ ability to understand the Arab-Israeli conflict, but shape how they understand power, legitimacy, and justice in history. The inclusion of oral histories and more balanced source material is crucial. Without doing so, students cannot fully understand the causes and consequences of the conflict, nor can they evaluate historical claims with the critical thinking skills the C3 Framework demands.

As a future educator, I believe I have a responsibility to teach with integrity and eliminate bias in order to give my students the most complete understanding of history I can. That means resisting overly sanitized or one-sided curricula and ensuring my classroom is a space where multiple narratives are included and analyzed. The ICS curriculum, in its current form, does not meet that standard.