Nefertari Yancie and Rebecca Macon Bidwell

University of Alabama at Birmingham fff

As society has changed, women’s roles have also changed. Women and their impact on history have been largely ignored in traditional textbooks (Clabough, Turner, & Carano, 2017). According to the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS), including women in the dialogue about history is important for helping students develop their own identities (NCSS, 2010). Set in the segregated South, the movie Hidden Figures (Melfi & Gigliotti, 2016) told the story of four female mathematicians battling both racism and sexism at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) during the 1960s. Stories such as the one told in Hidden Figures integrate women into the curriculum. Social studies trade books are one teaching tool that can be used to spotlight women’s roles in history.

This article describes how to use trade books to integrate women into the middle school social studies curriculum. The activities described take students through a series of steps to read and analyze trade books depicting women throughout history. The three women discussed in the activities are Catherine the Great, Hatshepsut, and Joan of Arc. Following a brief literature review about the benefits of using trade books in the middle school social studies classroom, the authors provide three different activities used to integrate women into classroom instruction. The steps and resources to implement the three activities are given. Additionally, an appendix is provided that contains a list of other trade books about women and their impact on history.

Benefits of Using Trade Books in the Social Studies Classroom

Teachers should utilize a variety of resources to actively engage students in the middle school classroom (AMLE, 2010). Trade books are one resource social studies teachers can use to examine historical figures and events in more depth (Schell & Fisher, 2006). Most social studies textbooks dedicate only a column or a page to a historical figure. In contrast, the text and illustrations in trade books enable students to explore the values, biases, and idiosyncrasies of people from the past (Edgington, 1998). This makes it easier for students to make an emotional connection with historical figures (McGrain, 2002).

Trade books allow students to examine the content material in meaningful ways. The pictures, text, and other primary sources in a trade book work together to focus on a historical figure, event, or topic (Lynch-Brown, Short, & Tomlinson, 2014). This enables students to infer, problem solve, and make predictions. Biographical trade books present students with situations and/or obstacles that historical figures faced. Students think critically when they can place themselves in the shoes of the person and ask, “How would I have handled this?” This question and similar ones should be answered based on evidence from the text and the pictures, as well as further research on the part of the students. These processes reflect the current emphasis on literacy-based practices and inquiry-based teaching advocated for in the C3 Framework (NCSS, 2013).

The simpler word and sentence structure in trade books make them useful when teaching social studies content. Struggling readers and ESL students find it easier to read and understand the content (Clabough, Turner, & Wooten, 2015). The easier readability level aids in comprehension, which allows struggling readers to grasp the essential content. The illustrations in trade books also facilitate the students’ ability to generate meaning of the text (Clabough et al., 2015). The different components in trade books allow students at all academic levels to be successful when learning social studies content. In the next sections, three activities are provided that allow students to connect in meaningful ways to female historical figures. The activities highlight the unique challenges women faced as their positions in society changed.

Finding Clues about Catherine the Great

An important benefit of working with trade books is that students are able to see multiple layers of historical figures. Social studies teachers often teach abstract traits such as progressiveness, fairness, and ruthlessness. There are people in history who encompass all of these characteristics, and trade books can help students to examine the social, political, and cultural context under which these people were shaped. As a result, they can also come to understand that all people are riddled with contradictions (Fresch & Harkins, 2009).

A trade book that shows complexity and depth in a historical figure is Catherine the Great: Empress of Russia (Vincent, 2009). Much focus is paid on Catherine’s reign, as she seized power from her husband and ruled Russia as a progressive queen for over 30 years. The following activity provides students with an opportunity to foster their analytical skills by examining the reign of Catherine the Great. The teacher begins the activity by reading the trade book aloud to the class. Students focus on the part of the book where Catherine shows herself to be a strong, arguably ruthless, leader who also embraced reforms, such as creating schools for young girls and encouraging the use of modern sciences and medicines.

After the reading of the text, the students are divided into pairs. Each pair is given two pictures of Catherine the Great and a graphic organizer. There is a prompt on the graphic organizer that reads as follows: “Catherine the Great was a queen who was controversial. What kind of ruler was she? Use clues from the pictures to answer the question.” The graphic organizer consists of two boxes that are side by side. Each box contains a different picture of Catherine the great and space for students to write down at least four “clues” about the pictures. The teacher informs the students that they only use the images for the clues to help them answer the prompt. For each detail, students should also briefly explain their reasoning by using evidence from the trade book to support their claims. A sample graphic organizer is provided in the next section.

Possible Student Example of Graphic Organizer

The teacher brings the class together to discuss the clues they discovered in each picture and what they believe the details say about Catherine the Great as a ruler. This is an opportunity for students to share and learn from each other. They can explain their thinking processes and also defend their ideas with evidence from the paintings and the trade book. After the discussion, the teacher provides students with the instructions for the writing activity. Students write two paragraphs that consist of five to eight sentences each. Using clues from their graphic organizers as supporting details, they compare and contrast Catherine the Great’s two leadership styles. The writing piece also needs to include how students believe Catherine should be remembered as a ruler. The authors have given an example of the writing activity in the next section.

Possible Student Example of Writing Activity

Catherine the Great had two aspects to her style of leadership. She was an avid learner of the Enlightenment philosophers and wanted to learn about their philosophies to make the lives of her subjects better. Political thinkers were invited to Russia, and Catherine would speak with them about their ideas. This resulted in her creating reforms such as opening schools for girls. However, Catherine the Great also had another side to her leadership style.

Catherine could be very controlling. While Catherine did use the military to expand the borders of Russia, she also used the military to take control of Russia from her husband, Peter. The Church’s land and wealth were taken over, which meant the Church had to answer to her. Catherine was progressive-minded, but she did not do much to help the millions of serfs in Russia. However, there are other reasons history should remember her as a good ruler. She was smart enough to take power from her husband because he was not ruling in the best interest of the people. Politicians and other nobles appreciated that she listened to them, and the common people were grateful for the reforms that were established in Russia. Catherine had absolute control over Russia, but so did other rulers of countries during the same time period. During this time, a person had to be strong to rule, and Catherine showed she had the strength to keep power.

This activity is beneficial to students because it utilizes trade books in a manner that usually cannot be done with textbooks. Textbooks usually provide superficial information about a historical figure, barely scraping the surface of how the time period’s culture, traditions, and politics shaped the person’s decisions and actions. Trade books can bring historical figures to life by allowing students to see the contradictions that exist within people. For instance, Catherine the Great fully embraced the Enlightenment philosophies, while at the same time doing very little to ease the oppression of Russian serfs. Activities with trade books allow students to see figures from the past as three dimensional and requires them to think on a higher level (Brooks & Endacott, 2013; Edgington, 1998). The analysis of the seemingly divergent aspects of Catherine’s personalities may lead students to understand that history is not black and white, but many shades of gray.

Dedicating Hieroglyphics to Hatshepsut

Janice Trecker (1973) offered insight into how little women were featured in U. S. History high school textbooks of the 1960s. As a result, when asked to name women from American history, students could name very few. Today’s history textbooks may include more women, but the information remains limited (Allard, Clark, & Mahoney, 2004). Trade books are resources teachers can use to fill the gap often left by textbooks. The rich content and pictures provide students with material that demonstrates how women have not only contributed to history but accomplished great deeds.

A trade book that illustrates a woman in a leadership role is Hatshepsut: His Majesty, Herself (Andronik, 2001). Hatshepsut’s life is explored, from her childhood to her rise as a successful female pharaoh. The following activity highlights the section of the book where Hatshepsut has her greatest temple built, the “Holy of Holies.” The teacher reads aloud how the carvings on the walls of the temple depicted Hatshepsut’s life, accomplishments, and how the gods chose her to rule. The will of the gods was often interpreted by priests and inscribed on walls of temples, along with great stories about the prowess and great attributes of the pharaoh. This activity has students create their own inscriptions for the wall of Hatshepsut’s temples. They use hieroglyphics to tell about her life and great deeds. The message in the hieroglyphics are supported by evidence in the trade books. It is recommended that the teacher provides students with a copy of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic alphabet and symbols that mean entire words, such as “pharaoh.” Examples of Egyptian hieroglyphics can be accessed at https://www.ducksters.com/history/ancient_egypt/hieroglyphics_examples_alphabet.php and http://www.landofpyramids.org/egyptian-hieroglyphics.htm.

Students use the hieroglyphics as a guide. They pretend to be scribes who are instructed to engrave into the walls of the Holy of Holies why Hatshepsut is such a great ruler. The hieroglyphics are drawn on paper that is provided by the teacher. The drawings must use a combination of the alphabet and symbols to describe Hatshepsut’s accomplishments and her attributes as a leader. The “engravings” must be supported by at least two details from the trade books. See the following as an example.

Possible Examples of a Student Engraving

After completing the hieroglyphics, students write a paragraph that consists of six to ten sentences. The paragraph must explain the meaning of the hieroglyphics, and students must cite at least two details from the text to support their claim. In addition, they are to express whether they believe it was an accomplishment for a woman to attain the position of pharaoh during this time period. Students give at least one reason to support their answer. The authors provide a possible example in the following section.

Possible Example of a Student Paragraph

Hatshepsut was a woman who declared herself pharaoh and reigned over Egypt at a time when women were not supposed to rule by themselves. She even dressed as a man by wearing a short kilt instead of a long dress and tied a gold beard to her chin. The hieroglyphics show this by the man and woman side by side next to the symbol for crown. Many Egyptian pharaohs wanted to be remembered by building great monuments. Hatshepsut built a famous temple that is called the Holy of Holies, which is portrayed by the symbol for a temple. The temple was built under the watchful eye and blessing of the god Horus. The falcon represents him. It was an accomplishment for Hatshepsut to attain the position of pharaoh during this time period. In ancient Egypt, there was not a word in the language for a female ruler so by becoming pharaoh she carved her own place in history by ruling Egypt for 22 years.

Trade books provide an in depth look into the lives of historical figures (Edgington, 1998). Textbooks tend to glance over events that define and shape the lives of a person. This activity allows student to examine such pivotal moments and examine how culture, the time period, and societal norms shape a historical figure’s actions and decisions. It is important for students to be able to view people from the past in historical context (Brooks & Endacott, 2013; Colby, 2010). By knowing the political, social, and cultural customs of the era, students gain insight into why people made certain decisions as well as better understand the ramifications of a woman taking a leadership role of the pharaoh.

Tweeting with Joan of Arc

Social studies textbooks often give limited versions of stories that deserve to be told in greater detail. Trade books can be used to tell the accounts of people and events in a manner that students find engaging and interesting (McGrain, 2002). This is especially true with biographical trade books about women. The challenges women faced were as unique as the methods chosen to meet them. Students will find themselves invested in the lives of these historical women as they learn about the courage it took to succeed in a male-dominated world.

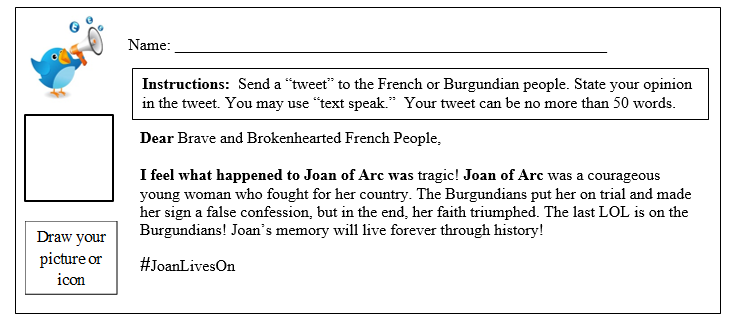

Teachers can use the trade book Joan of Arc to help foster students’ empathy as they explore the values, beliefs, and courageous actions of a teenage girl (Demi, 2011). This activity focuses on the section in the trade book when Joan was captured by the Burgundians, put on trial, and executed. The teacher reads aloud to students and shows the illustrations of Joan’s journey from arrest to execution. Then, each student is given a “Tweet” handout. The worksheet resembles a tweet with some of the same features students would find on an actual Twitter account. Students assume the role of a person from Joan of Arc’s time and write a tweet as the historical figure. They should use all of the literary mechanisms employed by Twitter, such as the acronym LOL, which stands for “laugh out loud.”

The teacher instructs students to send a tweet to the Burgundian or the French people where they are stating their opinion about the fate of Joan of Arc. A prompt should be included on the handout. A possible prompt may include the following. “Dear (insert French or Burgundian people), I feel what happened to Joan of Arc was (insert a descriptor)! Joan of Arc…” Students support their opinion about what happened to Joan at the hands of the Burgundians. They are required to use at least one supporting detail from the book to support their opinion. There is a 50-word count, which does not include the prompt. This word limit challenges students to edit their work so it must include the most relevant information.

The hashtag comment at the end of the tweet should reflect

the message and its overall tone. For instance, if a student’s tweet is angry,

the hashtag comment should reflect the same emotion. After completing the

activity, the teacher brings the class together and allows students to read

their tweets aloud. The authors have provided a possible example of a tweet in

the next section.

Possible Student

Example of a Tweet

Trade books draw students into the lives of biographical figures. In order for students to respond empathically, they need to be able to see another’s perspective (Ashby & Lee, 2001). The ability to see perspectives and express empathy is essential in social studies. If students are going to be engaged in the classroom, they need to connect and care about the historical figures being studied (Brooks, 2008). When students become invested in the lives of people from the past, they want to understand the decisions that were made, and this may lead to a deeper and more meaningful exploration and understanding of the content. Trade books are a resource that bridges the gap left by textbooks while at the same time helping to develop skills, such as empathy, that are necessary in the social studies classroom.

Closing Remarks

Social studies teachers face the challenge of engaging students in the middle school classroom. It can be difficult to encourage middle school students to find meaning and relevance in people, places, and events that existed hundreds and even thousands of years ago. Too many history textbooks tend to treat important historical figures and events like a 30-second bulletin on a news broadcast. Biographical trade books allow students to experience the lives of historical figures in depth. Through the pictures and text, students are able to make emotional connections with people from the past (Schell & Fisher, 2006). Historical figures are no longer names mentioned briefly on a page but become real people who faced obstacles and triumphs. Students have a better chance of empathizing with historical figures’ situations, challenges, and choices (Ashby & Lee, 2001).

Trade books also provide social studies teachers the opportunity to highlight the many women that have shaped history. Often, textbooks underrepresent women and their contributions to society (Allard, Clark, & Mahoney, 2004). Activities like those discussed in this article allow students the opportunity to utilize trade books to examine the lives of women in meaningful and interactive ways. This makes the inclusion of people from all backgrounds and cultures essential. An appendix is given that contains additional trade books focusing on women. AMLE’s This We Believe (2010) places an emphasis on diversity in culture, background, and gender. Trade books and associated activities enable students to have a more diverse view of history than may be possible with social studies textbooks.

References

Allard, J., Clark, R., & Mahoney, T. (2004). How much of the sky? Women in American high school history textbooks from the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s. Social Education, 68(1), 57-67.

AMLE. (2010). This we believe: Keys to education young adolescents. Westerville, OH: Author.

Ashby, R. & Lee, P. (2001). Empathy, perspective taking, and rational understanding. In O. L. Davis Jr., E. A. Yeager, & S. J. Foster (Eds.), Historical empathy and perspective taking in the social studies (pp. 1-21). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Brooks, S. (2008). Displaying historical empathy: What impact can a writing assignment have? Social Studies Research and Practice, 3(2), 130-146.

Brooks, S. & Endacott, J. (2013). An updated theoretical and practical model for promoting historical empathy. Social Studies Research and Practice, 8(1), 41-58.

Clabough, J., Turner, T., & Wooten, D. (2015). Up, up, and away: Using heroes of flight with middle graders. Tennessee Reading Teacher, 40(2), 5-14.

Clabough, J., Turner, T., & Carano, K. (2017). When the lion roars everyone listens: Scary good middle school social studies. Westerville, OH: Association for Middle Level Education.

Colby, S. R. (2010). Contextualization and historical empathy. Curriculum & Teaching Dialogue, 12(.5), 69-83.

Edgington, W. D. (1998). The use of children’s literature in middle school social studies: What research does and does not show. Clearing House, 72(2), 121-126.

Fresch, M. J., & Harkins, P. (2009). The power of picture books: Using content area literature in middle school. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Lynch-Brown, C., Short, K., & Tomlinson, C. (2013). Essentials of children’s literature (8th ed.). London, UK: Pearson.

McGrain, M. (2002). A comparison between a trade book and textbook instructional approach in a multiage elementary social studies class. (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1268&context=ehd_theses

Melfi, T. & Gigliotti, D. (2016). Hidden Figures [Motion picture]. United States: 20th Century Fox Studios.

NCSS (2010). National curriculum standards for social studies: A framework for teaching, learning, and assessment. Silver Spring, MD: Author.

NCSS. (2013). The college, career, and civic life (C3) framework for social studies state standards: Guidance for enhancing the rigor of K-12 civics, economics, geography, and history. Silver Springs, MD: Author.

Schell, E. & Fisher, D. (2006). Teaching social studies: A literary-based approach. London, UK: Pearson.

Trecker, J. L. (1973). Women in U.S. history high school textbooks. International Review of Education, 19(1), 133-139.

Three Trade Books Referenced in the Article

Andronik, C. M. (2001). Hatshepsut: His majesty, herself. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing.

Demi. (2011). Joan of Arc. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Children.

Vincent, Z. (2009). Catherine the Great: Empress of Russia. London, UK: Franklin Watts Publishing.

Appendix of Additional Trade Books Focusing on Women’s Roles in History

Empress Cixi

Price, S. S. (2009). Cixi: Evil empress of China? London, UK: Franklin Watts Publishing.

Frida

Brown, M. & Parra, J. (Illustrator). (2017). Frida Kahlo and her animalitos. New York: NY: NorthSouth Books.

Jane Addams

Stone, T. L. (2015). The house that Jane built: A story about Jane Addams. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Joan Trumpauer Mulholland

Mulholland, L., & Janssen, C. (Illustrator). (2016). She stood for freedom, the untold story of a civil rights hero: Joan Trumpauer Mulholland. Salt Lake City, UT: Shadow Mountain.

Josephine Baker

Powell, P. H. & Robinson, C. (Illustrator). (2014). Josephine: the dazzling life of Josephine baker. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books LLC.

Marie Curie

Demi. (2018). Marie Curie. New York: NY: Henry Holt and Co.

Mary Tudor

Buchanan, J. (2008). Mary Tudor: Courageous queen or Bloody Mary? Danbury, CT: Children’s Press.

Michelle Obama

Parker, M. G. & Birge, M. (Illustrator). (2009). I am Michelle Obama: The first lady. Atlanta, GA: Tumaini Publishing LLC.

Queen Victoria of England

Whelan, G. & Carpenter, N. (Illustrator). (2014). Queen Victoria’s bathing machine. New York: NY: Simon & Schuster.

Sara Roberts

Goodman, S.E. & Lewis, E.B. (Illustrator). (2016). The first step: How one girl put segregation on trial. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Sacajawea

Willard, J. (1918/2017). Bird Woman (Sacajawea) the guide of Lewis

and Clark: Her own story now first given to the world. Los Angeles, CA:

Enhanced Media Publishing.