Beyond the Box Score

Chris Carman

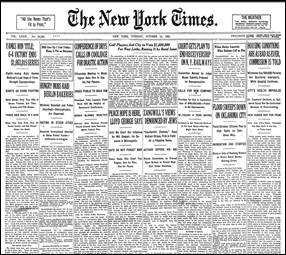

October 15th, 1923. John McGraw’s New York Giants versus Miller Huggins New York Yankees in game six of the World Series. At the beginning of the Yankees season, The House That Ruth Built was opened to the public in April of that year. Babe Ruth opened the stadium and set the tone for that season by hitting three home runs along with eight walks. That tone stayed up until the day at the Polo Grounds stadium in Upper Manhattan where McGraw’s dream of three straight championships in a row was crushed. Allowing the New York Yankees to win their very first World Series championship.

The Yankees winning the World Series was the very first article on the front page of this New York Times article which claims that this game six was very intense and had many back-and-forth moments between the Giants and the Yankees throughout. Both teams also have at least one key player that had a large impact on the game, for the Yankees, Babe Ruth of course, and for the Giants, it was their pitcher Art Nehf. As the author of this article calls him, “the last hope of the old guard,”[1] had only allowed two hits in the first seven frames and allowed one home run from Ruth. Nehf had been too powerful against the Yankee hitters with his great speed and side-breaking curve made it from the third inning to the eighth the Yankees went hitless. While also being three runs behind and the Yanks getting no love from the crowd in the Giant’s home stadium, the situation was looking grim for Huggins and his team.

When the eighth inning hit, things still seemed to be looking good for Nehf, but during the second pitch of the inning is when the tide started to turn. The ball flew close to Walter Schang’s ear, he tried to move and ended up hitting the ball to third base for a single. After this hit, two more Yankee players hit and were able to get Schang home to only put them two behind the Giants. According to the article, “Nehf’s face turned as white as a sheet,”2 something happened to him after the few hits he gave away and he couldn’t continue. Bill Ryan, the backup pitcher, came in to try and salvage what we could from the wreckage that Nehf left. Ryan started pretty well and almost made it out of the inning until Bob Meusel hit the ball slightly to the right of Ryan into center field. Three runs were scored on that hit, five for the inning making the World Series almost over at that point.

With that eighth-inning rally, the Yankees were able to put the game away and win their very first World Series Championship.

The next big article that is on the front page of this New York Times article is that hungry mobs raid Berlin bakeries. At this time in 1923, five years ago, Germany had just lost World War One and was facing some pretty terrible consequences from the Allied powers. One of these consequences was that Germany was not doing a good job paying their war reparations to the French and therefore decided to occupy the Ruhr district. This area was known for having many raw materials that the French would take for themselves as payment for German war debts. In these articles in the New York Times, it is fascinating to see the differences in rioting in German cities like Berlin and Frankfurt versus French-occupied ones such as Neustadt and Düsseldorf. The first half of this article talks about Berlin and Frankfurt which were two cities that were still controlled by the German government but were wrecked by inflation of bread prices. This was because the government decided to print more money to have enough for their war debts. The problem with printing more money is that it creates more physical currency, but decreases its value. After the government did this, the value of the German mark went to almost no value, and prices of bread skyrocketed. This article says that “5000 demonstrators, mostly unemployed men, reinforced by women with market baskets… marching to the Rathaus and making demands upon the authorities… The police reserves were called and drove demonstrators away.”[2] Inflation wrecked the economy so badly that the German people were unable to afford for their families and protested in the capital city to show the disarray of the German state.

The second half of the article talks about the cities of Neustadt and Düsseldorf, two cities that were occupying the territory as stipulation states in the Treaty of Versailles. In Neustadt, crowds of unemployed people were attempting to raid a post office that was reported to be holding currency inside of it. French authorities were sent out to break up the crowd. In Düsseldorf, communists and nationalists were working together to foment trouble in the Ruhr district. In the article, the author states one key difference between the riots in this city compared to Berlin. “According to a statement made this morning the movement is political rather than economic. It was aimed against Chancellor Stresemann (German foreign minister) on the one hand and against the French on the other.”4 These people were not rioting because they didn’t have enough food, these people hated the fact that they were being ruled by a foreign power. I found this section of the newspaper very interesting because knowing what happened later on with Hitler coming to power, the German people despised the Treaty of Versailles and were willing to shift political extremes to get rid of it.

There are sections in this article commenting on the rising poor conditions of the German government during the 1920s. This article is from the perspective of Reed Smoot, Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Called at the White House to tell the president about the conclusions reached after his recent trip to Europe.

After his trip, the senator had some definite opinions on the Americans revisiting the appointment of the Hughes proposal to determine the ability of Germany to pay their reparations from the war. This plan was an idea that the International Commission should fix the amount of money that the Germans would have to pay back. Smoot wanted all countries in the commission to agree on this plan and was expecting the French to back down on their reparation demands. To be fair, most of World War I was fought on French territory in the northern regions of the country needing these reparations fo rebuilding.

The Senator knows that France will most likely not agree with this arrangement but is scared about the future of Europe. He said to the president, “Unless something was done quickly, there was danger of an outbreak which might involve all of Europe.”[3] Too bad that Smoot was right about this and nothing was done with this issue. It is the very reason that the Allies did not relax reparations and kept demanding from a destroyed Germany that Hitler was able to become Chancellor a decade later.

The next big headline of this New York Times newspaper article comes to the news in the United States. This headline was about a conference of drys calling for President Calvin Coolidge to take action against the people who were breaking rules on the prohibition. The counsel of the drys or people who were against liquor consumption saw the amount of people who were smuggling illegal booze by sea and wanted them to stop doing this. They wanted the president and the American people to uphold the Eighteenth Amendment. Smuggling liquor by sea was one of many alternatives that citizens were finding to get around Prohibition in the 1920s. Rum Row was the name of a naval liquor market along the East Coast that was just beyond the American maritime limit where transactions of alcohol were made. Bootleggers, or people who engaged in the illegal sale of alcohol, would just have to sail out to this region in a small boat to pick up shipments of liquor to resell back in the States. The last small section of this article is direct quotes from the president calling for legislators to abide by the laws and punish people who are breaking the laws of the Constitution.

He says, “The State or Federal Constitution should resign his office and give place to one who will neither violate his oath nor betray the confidence of the people.”[4] Some corrupt politicians were becoming bootleggers themselves or were not punishing people who were breaking the law, which is why the president had to make this statement to these legislators. Coolidge ends his statement by saying, “Lawmakers should not be lawbreakers.”7

There is another section farther in the New York Times article that is from the perspective of another Representative traveling to another country to report on the country they are traveling to. In this case, it is Fred A. Britten of Illinois returning from his visit to Russia having changed his mind on the recognition of the Soviet government. Much like Reed Smoots, Britten called upon the president to give his reports and experience after being in the new Soviet Union for some time.

Unsurprisingly, the representative started his report to the president by saying, “The Soviet regime was a visionary Government whose very foundation is baked on murder, anarchy, Bolshevism and theft.”[5] Knowing when this article was written and being three years past the first Red Scare in the United States, one could only imagine his thoughts on the regime in Russia. Many states in the US around the early 1920s were outlawing advocacy of violence in attempting to secure social changes and most people suspected of being communist or left-wing were jailed. Another thing to mention is that this first Red Scare did not distinguish between Communism, Socialism, Social Democracy, or anarchism and all were deemed as a threat against the nation.

Britten mentions that he “traveled unofficially, sought no favors, and tried to see the good side of that tremendous political theory which is now holding 150,000,000 people in subjection.”[6] It is debatable whether he was trying to see the good side of Russia or not. He also talks about the major difference in how religion is treated in Russia. Atheism is what was primarily taught in the Soviet Union because religion was seen as a bourgeois institution whose only goal was to make money off of followers. Britten mentions some signs that he saw, one by the entrance to the Kremlin Palace that read, “Religion is the opium of the State,”[7] and another one that said, “Religion is the tool of the rich to oppress the poor.”11 Communism is very different from capitalism which is why two different Red Scares happened in the United States to protect itself from an ideology that was very different from its own.

How can this topic benefit teachers?

The prompt for this paper was to find a significant baseball box score from the 1900s of our choosing. I selected the Yankees’ first-ever World Series win against the New York Giants, using the Historic New York Times Database. We were then instructed to examine the other articles published in that same newspaper issue. For example, I focused on reports of hunger strikes in Berlin, which were driven by the collapse of the German mark and soaring bread prices after World War I. This was the first major assignment of the class, designed to help us begin developing primary source research and analysis skills, an essential foundation for any history course.

Teachers don’t have to limit this to a baseball history lesson; it can easily be adapted to focus on any major topic in U.S. history from the 1900s and beyond. Students can begin with a key event as the entry point for their primary source research. Then, they can expand their analysis by identifying and writing about other events covered in the same newspaper issue, painting a fuller picture of what was happening in the U.S. during the chosen time period. This strategy not only sharpens students’ analytical skills but also broadens their understanding of how historical events overlap and influence one another, helping them grasp the interconnectedness of social, political, and cultural developments within a given era.

References

“Britten Opposes Soviet Recognition.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 16, 1923: Page 5 https://login.tcnj.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers /yanks-win-title-6-4-victory-ends-1-063-815-series/docview/103153313/se-2.

“Conference of Drys Calls on Coolidge For Drastic Action.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 16, 1923: Page 1.

“Hungry Mobs Raid Berlin Bakeries.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 16, 1923: Page 1.

Oversimplified. “Prohibition – OverSimplified.” YouTube video, December 15th, 2020.

“Smoot and Burton See Peril In Europe.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 16, 1923: Page 3.

“Yanks Win Title; 6-4 Victory Ends $1,063,815 Series.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 16, 1923: Page 1.

[1] “Yanks Win Title; 6-4 Victory Ends $1,063,815 Series,” New York Times (1923): 1. 2 “Yanks Win Title,” 1.

[2] “Hungry Mobs Raid Berlin Bakeries,” New York Times (1923): 1. 4 “Hungry Mobs Raid,” 1.

[3] “Smoot and Burton See Peril In Europe.” New York Times (1923): 3.

[4] “Conference of Drys Calls on Coolidge For Drastic Action,” New York Times (1923): 1. 7 “Conference of Drys,” 1.

[5] “Britten Opposes Soviet Recognition,” New York Times (1923): 5.

[6] “Britten Opposes Soviet,” 5.