Teaching “What to the Slave Is the 4th of July?” by Frederick Douglass:

A Two-Part Student-Led Lesson

Jeff Schneider

Reprinted with permission (https://historyideasandlessons.substack.com/p/teaching-what-to-the-slave-is-the-66e?r=710fi&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web)

Now that Ron DeSantis has caused a widespread walkout by Florida college students defending both their right to diversity and the free exchange of ideas in the classroom, and he virtually outlawed any teaching of conflict in Black history, it is evident that he will run into serious roadblocks in his campaign to rule the whole country with an iron fist. The increasingly cloudy and claustrophobic atmosphere emanating from the formerly sunny state of Florida begs for an eloquent and big-hearted response. The following two-day student-led lesson will introduce American history students to one of our leading intellectuals and, arguably, the greatest speaker of the 19th century: America’s teacher, Frederick Douglass. He never fails to impress.

Day one

The assignment I give the students for the first day is to download and read the first 10 pages of “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” They choose one sentence from each page for homework, write it down on a separate sheet of paper, and explain underneath each one why they chose it. They are to read to the end of the top paragraph of the second column of page 10. The students are asked to underline their sentences on the PDF. It is necessary to collect the homework at the beginning of the class in order to make sure each one of them did their own work. Since they had underlined their sentences on the PDF, the students did not need their homework for class. I asked the students to write the first 5 words of those sentences on the blackboard. I picked the students randomly by jumping around asking for their fifth sentence or their first sentence or their eighth sentence and so on. Each student was to sign their name and sit down. Before class I had drawn 10 vertical lines with one horizontal line across the middle, forming 20 boxes on the board for the students to write in. I placed two pieces of chalk under each vertical group of two boxes so that the writing could go faster. The teacher should know the speech inside and out to create an ease of discussion. It makes the class more interesting. While the students were writing the words they had to start at the beginning of their sentence and make sure that no one else had picked the same sentence. From the time the students were entering the class through the writing on the board, I played a song by the Melodians called “By the Rivers of Babylon.”

Once the students had finished writing on the board, they sat down, and I asked literally “Who has comments or questions?” Nothing more: no suggestions or hints. Usually, they remarked how impressed they were by Douglass’ intelligence and language, or they mentioned how understandable the speech was. They found it a shock to read the work of an escaped slave who could write with clarity and on such a high level of complexity. After the comments died down, I would ask the class to turn to page 6 and look at the bold indented passage in the first column. The students recognize the words of the tune they had just listened to. They appeared in the speech from 1852! I played the song again and asked why Douglass had quoted the verse. Some students might have heard the song because their parents or grandparents had played it at home: It is from the soundtrack of the movie “The Harder they Come” from 1972. Alternatively, some might know that it is the Old Testament Psalm 137 that Douglass quoted. I asked if there were any words they did not understand in the passage, or if someone had picked that passage or would like to comment on it, even if they had not picked it. Someone might want to know what Zion was or eventually someone would notice that the exiled Jews were asked to sing one of the songs of Zion, their homeland. Many thousands of Jews were enslaved in Babylon from 586 BCE to about 538 BCE. It was great insult to be asked to sing for their enslavers the students could conclude. Africa is Zion for Douglass someone might say.

Now it was time to begin analyzing the sentences that the members of the class had chosen. As I called on the students to read their sentences, I asked them to point out the page, the column, and first words of the paragraph where the sentence appeared. The students must read slowly and loudly so that the others can get the meaning. “Why did you choose that?” I asked. Often the student explained what it meant but not what attracted them to it. I would ask what they thought or why they liked it or impressed them or not. Sometimes, I would ask who else wanted to comment, but it is not possible to do that more than a few times because there is not enough time in a period to keep discussing one sentence. The students did not often choose the long period sentences that took up whole paragraphs. Most of those we would pick up later because they are the emotional heart of the speech.

When there is time at the end of each class, I asked the students for their favorite sentences and had them read these out loud. The speech is so powerful partly because the rhythm of the words, the internal rhymes and alliterations drive you on. Reading the “Fourth of July Oration” is a real learning experience: Douglass employs grand and deeply affecting rhetoric to illuminate wrongs of slavery. It also shows the great power of the Declaration of Independence despite its obvious hypocrisy. These contradictions have led to tragic cancellations of the Declaration by Nikole Hannah-Jones of The 1619 Project and others. The importance of the study of slavery and of the Declaration has been confused by these journalists who are not trained historians.

In the course of this exposition of my lesson on Douglass’s speech, I will discuss sentences frequently chosen by the students. We had to leave out much of the speech, but what we did in class explored the breadth and depth of the oration giving the students giving them the confidence that they had discussed the work in detail and that they had directed the learning themselves. I had them write a paper on the speech by first summarizing it, choosing 2 ideas in the speech and explaining what each meant and why they were important. They often produced wonderful papers because we had gone over the Oration in sufficient detail. They were comfortable in their interpretations and almost everyone was excited by the assignment. I chose one essay each year to go in our social studies magazine.

Now we are ready to dive into the speech itself.

Douglass’ introduction

At the beginning of the Oration, Douglass confesses his trepidations about the task before him. Despite his close relationship with the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society and the Corinthian Hall, where he had spoken many times, he declared, “The fact is ladies and gentlemen the distance between this platform and the plantation from which I escaped, is considerable. . . That I am here today is a matter of astonishment as well as gratitude.” The students will know that he was born into slavery. “This, for the purpose of this celebration, is the Fourth of July.” “Why did you choose that?” I asked. The students will realize he is not speaking on July 4th. Instead, he said that he is protesting the day right from the start. Many versions of the speech on the web, in fact, begin with that sentence. He continues, “It is the birthday of your political independence and political freedom,” starkly using the second person plural that he was not speaking of his liberation, but theirs. All this the students can glean after you ask why did you choose that? He then compares the day to Passover when the Jews, the “emancipated people of God,” were delivered from bondage in Egypt. The students will notice that there are numerous quotes from and references to the Bible.

Douglass’ writing is so densely packed that the ideas rush at you as you read. He points out that the country is “young,” only “76 years old,” in 1852; That it is a topic for rejoicing, noting that a young river that can change its course more easily than an old river or a country thousands of years old. He adds that the nation is still in the “impressible stage of its existence . . . Great rivers are not easily torn from their channels worn deep by the ages . . . [but while] refreshing and fertilizing the earth . . . they may also rise in wrath and fury and bear away on their angry waves the accumulated wealth of years toil and hardship. . . As with rivers so with nations.” Recently floods and tornadoes have been ravaging wide swaths of land and forests in nearly every part of the US. From the waters and winds of Hurricane Katrina to the floods of Hurricane Sandy to the fires and droughts in the far West, we have seen unprecedented levels of destruction. Eliciting these resonances with open-ended questions such as why did you choose that or what does that remind you of should be straight forward. At some point in discussing the speech it will be clear that Douglass is setting the context for discussing the effects of the multifarious and wholly predictable dangers of slavery to the body politic of the young nation.

The Revolution

In the second paragraph of the second page, he turns to his duty to the 4th of July itself. Addressing his “Fellow citizens,” he introduces the history of the Revolution explaining that in 1776 “your fathers were British subjects” who “esteemed the English Government as the home government” which “imposed upon…its colonial children such restraints, burdens and limitations…it deemed wise, right and proper.” However, these acts produced a widespread reaction by the future revolutionists not “fashionable in its day” because the colonists did not believe in the “infallibility of government” but “pronounced the measures unjust, unreasonable and oppressive.”

“To side with the right against the wrong, the weak against the strong and with the oppressed against the oppressor! here lies the merit and one which seems unfashionable in our day . . .” Here, is the first burst of eloquence from Frederick Douglass. The internal rhyme and the rhythm of these lines stand out. Douglass could astound the listener in just a few words. His eloquence matched the gravity of the cause. His description of the Stamp Act protests and the protests against the Townshend Acts and the Tea Tax bring us back to the streets and the harbors of our colonial past connecting his listeners to our heritage of activism.

But the colonists “saw themselves treated with sovereign indifference, coldness and scorn . . . As the sheet anchor [heaviest anchor] takes a firmer hold when the ship is tossed by the storm, so did the cause of your fathers grow stronger as it breasted the chilling blasts of kingly displeasure.” But “like the Pharaoh whose hosts were drowned in the Red Sea, the British Government persisted in the exactions complained of . . . Oppression makes a wise man mad. Your fathers were wise men. They did not go mad . . . They became restive under this treatment . . . With brave men there is always a remedy for oppression. Just here the (startling) idea of the separation of the colonies from Britain was born!” However, the opposition Loyalists or Tories “hate all changes . . . (b)ut silver gold and copper change! . . . amid all their terror and affrighted vociferations against it the alarming and revolutionary idea moved on and the country with it.” Are there words here you do not know, I ask. Mad of course refers to mental illness and restive means to be agitated. Vociferations are chants shouted by the demonstrators.

The revolutionists’ solution was to “solemnly publish and declare that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states and that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown.” This is the famous core of the Declaration by Richard Henry Lee that is in the penultimate paragraph of the document. It rings with preternatural force shocking the sleepy 18th century kings and subjects in the monarchies of Europe. Many American and British historians who still claim in 2023 that the Americans were provincials who had no good reason to rebel, but over the course of the next 7 years the British learned they had to accept the wishes of these “naive” colonists.

Douglass continues “I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt [fastener] to the chain of your nation’s destiny, so, indeed I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions in all places, against all foes and at whatever cost.” Students will realize that Douglass had great respect for the Declaration and the dogged persistence of the revolutionary forces.

Douglass says, “My business, if I have any this day, is with the present. The accepted time with God and His cause is the ever-living now.” A phrase I had to look up to confirm that it was Douglass”! “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present . . . Washington could not die until he had broken the chains of his slaves. Yet his monument is built up by the price of human blood and the traders in the bodies and souls of men shout — ‘We have Washington to our father.’– Alas that it should be so, yet so it is. ‘The evil that men do, lives after them, The good is oft’ interred in their bones.’” Douglass challenges his audience with that quote from Shakespeare: Mark Antony’s funeral oration for Julius Caesar.

He praises Washington for freeing some of his stolen human “property” before he died, but immediately pulls the compliment back by condemning the first president’s admirers for employing enslaved workers to build the Washington monument. “Can anyone comment on that?” I asked the students. Some members of the class might know that later the capitol building and the White House were also built by slaves. Now he is done with his task of recalling the Fourth of July.

The thesis

“Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? . . . I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us . . . The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. to drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me by asking me to speak here today?”

In discussing these lines above someone will point out that the stripes are the wounds caused by whips and also are the stripes on the flag. This was a common abolitionist trope utilized even in an Abecedarium, an alphabet book for children.

“Are there any words you do not know?” I asked. The students will probably not know what a pale is. Those were the segregated areas where Jews were confined in the shtetls of Russian-Poland, but also more precisely in this case the English confined themselves in a pale after conquering Northern Ireland. The idea of “American exceptionalism” was clearly a commonplace in 1852. His sarcastic description of the “grand illuminated temple of liberty” is shocking to see in his 1852 speech. Americans, even then, had a bloated idea of the purity of American democracy. He goes right for the jugular: Douglass states his thesis as his duty to defend the slave and his condition.

He refers in the paragraph above the Psalm to the violent retribution that Yahweh ( a Jewish name for God) at the Hebrews’ request to be visited upon the Babylonians for enslaving them and mocking them, which is rarely quoted by Christians. The shocking lines which Douglass avoided are in the King James Version of the Old Testament.

Then he quotes the first parts of Psalm 137 that we have encountered before: “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down. Yea! we wept when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there, they that carried us away captive, required of us a song; and they who wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How can we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.”

I asked the students to recall the song we heard at the beginning of the class in the light of our analysis so far. “How can you interpret these words now?” I asked. The students will conclude that the enslaved Jews were mocked by the Babylonians who asked them to sing a song of their homeland, Zion – just as he is in America singing the praises of the white people’s freedom document while his people are enslaved.

The thesis

“My subject, then fellow-citizens is American slavery. I shall see this day . . . from the slave’s point of view . . . I do not hesitate to declare… that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than it does on this 4th of July! . . . (T)he conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.” He dares to “call into question and to denounce . . . everything that serves to perpetuate slavery, the great sin and shame of America.” Then, quoting his teacher, William Lloyd Garrison, “’I will not equivocate, I will not excuse’ . . . and yet no one word shall escape me that any man whose judgment is not blinded by prejudice, or who is not at heart a slaveholder, shall not confess to be right and just.”

The students will conclude that the Declaration from the past is the founding document but has been desecrated and tossed aside by the slave holders in power in the country from then, through the present and into the future. Anyone who finds slavery to be repugnant will discern the truth in his arguments.

In order to continue with the lesson, over the next few pages (from the last paragraph of 6 to the middle of the second column on page 9), every sentence and every word is crafted to thrill the reader with Douglass’s intelligence and skill and cringe in horror as he speaks the truth of the brutality of American slavery. Each passage is another lesson in the illogic of the excuses for the system and cruel treatment perpetrated on the Black population in our so-called democratic and freedom-loving land. I will provide the teacher with sentences and clauses comprising a bare bones narrative. But most of this, must be read aloud in class. These paragraphs are too dramatic and inspiring to skip over. Here is a precis of the next few pages. I quote some of the sentences, but the full power is in the reading. Be sure to have the students read them. They will be shocked at how the words help them keep the rhythm with both understanding and expression: The images, the sounds, and the meters carry them, pushing and pulling them along. Douglass’s energy is so intense that the quotes never lose their power.

“Must I argue that the slave is a man?”

“Must I undertake to prove that the slave is a man? . . . Nobody doubts it . . . There are seventy-two crimes in the State of Virginia, which, if committed by a black man . . . (no matter how ignorant he be), . . . (acknowledging) that the slave is a moral, intellectual and responsible being . . . It is admitted in the fact that Southern statute books are covered with enactments forbidding, under severe fines and penalties, the teaching of the slave to read or to write… When you can point to any such laws, in reference to the… dogs in your streets, (or) when the fowls of the air, when the cattle on your hills, when the fish of the sea, and the reptiles that crawl, shall be unable to distinguish the slave from a brute, then will I argue with you that the slave is a man!”

When you ask how the students understand this sentence you are not done until they can say “Even animals see the enslaved as men, but the slaveholders cannot.” The students discover that the enslaved are expected to know right from wrong, but animals are not expected to. “For the present, it is enough to affirm the equal manhood of the Negro race. Is it not astonishing that, while we are ploughing, planting and reaping, using all kinds of mechanical tools, erecting houses, constructing bridges, building ships, working in metals of brass, iron, copper, . . . having among us lawyers, doctors, ministers, poets, authors, . . . living, moving, acting, thinking, planning, living in families as husbands, wives and children, and, above all, confessing and worshipping the Christian’s God, . . . we are called upon to prove that we are men! . . . Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? that he is the rightful owner of his own body?”

All the verbs, all the verbs strung together: An astonishing effect! So many powerful images in this paragraph.

“There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven, that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.”

Here we must stop and make sure the last thought is clear. The students must interpret this last sentence. Is there a word you do not know in this? A canopy is a covering. All men are beneath the canopy of heaven. The analysis is not complete until the students state that no man wants to be a slave. The listeners are cornered. The orator has taken their minds hostage.

And now one of the most powerful passages of all. “[T]o work them without wages . . . to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families.” The paragraph is a masterpiece. This is a sonorous but brutal description of violence complete with startling images, crafted with alliterations and internal rhymes. As above the reader must ask: Is he arguing or not while he claims not to argue at all? “What, then, remains to be argued? Is it that slavery is not divine; that God did not establish it; that our doctors of divinity are mistaken? . . . Who can reason on such a proposition? They that can, may; I cannot. The time for such argument is past.”

And now the most famous paragraph: “What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless . . . your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.”

“How do you comment on this?” I asked. It is a perfect description of systemic racism: Incontrovertible intersectionality. It is where Governor DeSantis’s views come to die.

Bringing slavery before the eyes

“Go where you may, . . . for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival. Take the American slave-trade, . . . This trade is one of the peculiarities of American institutions. It is carried on in all the large towns and cities in one-half of this confederacy; and millions are pocketed every year, by dealers in this horrid traffic.”

Here Douglass refers to the euphemism, “the peculiar institution,” which is supposed to assuage the guilt of the leaders of the so-called southern “civilization.” It is the hackneyed trope of a racist attempting to endear himself to his audience by turning slavery into a peccadillo. Continuing, he quotes the proposed paragraph written by Thomas Jefferson for the Declaration of Independence but rejected by the Continental Congress calling slavery “piracy” [manstealing] and “execrable commerce.” “Are there words here you do not know?” I asked. Excrement is human waste. Nearing the end of this paragraph, he denounces the scheme of colonization that our “colored brethren should leave this country and establish themselves on the western coast of Africa!”

“Behold the practical operation of this internal slave-trade, (The slave drivers) perambulate the country, and crowd the highways of the nation, with droves of human stock…They are food for the cotton-field, and the deadly sugar-mill. . . Cast one glance, if you please, upon that young mother, whose shoulders are bare to the scorching sun, her briny tears falling on the brow of the babe in her arms. See, too, that girl of thirteen, weeping, yes! weeping, as she thinks of the mother from whom she has been torn! . . . suddenly you hear a quick snap, like the discharge of a rifle; the fetters clank, and the chain rattles simultaneously; your ears are saluted with a scream, that seems to have torn its way to the center of your soul! The crack you heard, was the sound of the slave-whip; the scream you heard, was from the woman you saw with the babe. Her speed had faltered under the weight of her child and her chains! that gash on her shoulder tells her to move on.”

The students will comment that this paragraph is filled with images and rings with sounds of whips and clanging chains. The powerful ideas are matched by the thundering rhetoric keep you on the edge of your seat.

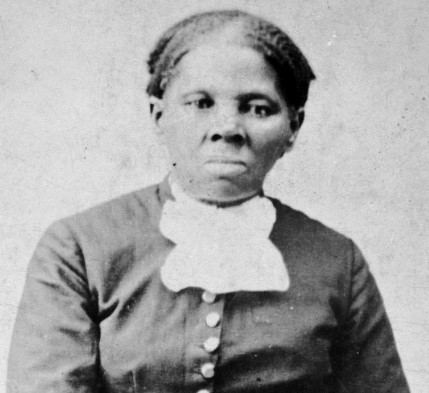

Then: “I was born amid such sights and scenes. To me the American slave-trade is a terrible reality. When a child, my soul was often pierced with a sense of its horrors. I lived on Philpot Street, Fell’s Point, Baltimore, and have watched…this murderous traffic (which) is, to-day, in active operation in this boasted republic. In the solitude of my spirit . . . My soul sickens at the sight.”

Students will see how he brings this experience directly to our hearts. Is this the land your fathers loved, the freedom which they toiled to win? Is this the earth whereon they moved? Are these the graves they slumber in? Students will react to the emotion in the lines of his childhood memories. The paragraph and the lines of the poem are poignance beyond measure. The lines by the abolitionist poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, are a tribute to the lost glory of the American promise. It can make the reader cry. When activists say that the “personal is political” there is no better example than this memory of Douglass’s childhood traumas. This concludes the first day of the lesson.

Top of Form

Day two

The second day I would ask the students to finish the speech, choosing 5 more sentences from pages 11 to 15 and to find places in the first 10 pages that explain that the slave is a man. They also were asked to point out the structure of the speech: where does the introduction end and the conclusion begin? Where is the thesis? Here we discussed the major sections of the speech which they could identify as the introduction, the Revolution, the section in which the thesis is stated and the proofs of why the slave is a man and why slavery is wrong. The speech’s final sections Douglass argues that slavery is not divine, examines the politics of slavery, and the Constitution, delivers a summary, and a peroration (conclusion).

American religion and The Fugitive Slave Law

“But a still more inhumane, disgraceful, and scandalous state of things remains to be presented. By an act of the American Congress, not yet two years old, slavery has been nationalized . . . (T)he Mason & Dixon’s line has been obliterated; New York has become as Virginia; and the power to hold, hunt, and sell men, women, and children as slaves . . . the liberty and person of every man are put in peril…. The oath of any two villains is sufficient, for black men there are neither law, justice, humanity, not religion. The Fugitive Slave Law makes mercy to them a crime; and bribes the judge who tries them. An American judge gets ten dollars for every victim he consigns to slavery, and five, when he fails to do so.”

“How can you comment on this?” I asked. This bribe is rarely mentioned in the standard discussion of the odious Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which of course, was part of the Compromise of 1850. In 2021 the vicious Texas anti-abortion bill borrowed its form and method of enforcement to this law. The reward of $10,000 has been substituted for the $10 in the 19th century law. It deputizes the whole population of Texas to arrest anyone who aids in arranging for an abortion. Douglass points out that the magistrates for the fugitive slave law were acting like the Protestant, John Knox, denouncing the Catholic supporters of Mary Queen of Scots who were threatening to murder Queen Elizabeth.

The leading American ministers “have taught that man may properly be a slave that the relation of master and slave is ordained of God . . . and this horrible blasphemy is palmed off upon the world for Christianity.” “How do you think about this,” I asked. Black men slave or free walking down the street even in the North were subject to false identification, imprisonment, and enslavement. It became a religious duty to show no mercy! What an abomination and evisceration of religious belief and practice. Are these Evangelical Christians in the Texas legislature or in 1852 practicing the teachings of mercy and forgiveness?

Douglass answers the question: “For my part, I would say, Welcome infidelity! welcome atheism! welcome anything—in preference to the gospel, as preached by those divines. They convert the very name of religion into an engine of tyranny, and barbarous cruelty, and serve to confirm more infidels, in this age, than all the infidel writings of Thomas Paine, Voltaire, and Bolingbroke, put together, have done! These ministers make religion a cold and flinty-hearted thing, having neither principles of right action, nor bowels of compassion.”

“Do you know these names,” I asked? Some students might know Thomas Paine or Voltaire. Bolingbroke was also a free thinker, an 18th century term for atheists, agnostics, and deists. Here Douglass claims he would favor these anti-slavery free thinkers, Thomas Paine, and Voltaire and he adds the dissenter Viscount Bolingbroke, claiming they were all three at least sympathetic to the plight of the enslaved. If students have a question, bowels of compassion refers to the deepest recesses of the human body, a common 18th and 19th century expression. These last lines are really shocking coming from such a religious man as Frederick Douglass.

“At the very moment that they are thanking God for the enjoyment of civil and religious liberty, and for the right to worship God according to the dictates of their own consciences, they are utterly silent in respect to a law which robs religion of its chief significance and makes it utterly worthless to a world lying in wickedness.” “How would you interpret that,” I asked. The students will come to the conclusion that Douglass is emphasizing the hypocrisy of the leaders of the congregations and denominations in the United States.

Douglass continues: “The American theologian, Albert Barnes uttered what the common sense of every man at all observant of the actual state of the case will receive as truth, when he declared that ‘There is no power out of the church that could sustain slavery an hour, if it were not sustained in it.’” “How do you understand that?” I asked. The students will reach a conclusion that this is a very broad statement. It is a condemnation undercutting all the pronouncements of the pro-slavery divines. In contemporary terms, this is a thought based in the ideas of systemic racism and embedded in the American economy and society. It is an example of intersectionality between religion and politics, an unmistakable interdependence, however much Ron DeSantis might argue to the contrary. In a previous passage, Douglass had pointed out that there were many minister abolitionists in Britain where the monarchy opposed slavery since the 1820s but very few in America where the weight of the church was behind the slaveholders. Above on page 12 of the speech he calls them out: the many pro-slavery American ministers and the few anti-slavery heroes in the United States.

And now we are coming to the ending of the speech. There are just two topics left before the Summary and Conclusion: America’s hypocrisy toward foreign nations and the nature of the Constitution.

American foreign relations

Douglass turns to yet another theater of hypocrisy in the United States. “Americans! your republican politics, not less than your republican religion, are flagrantly inconsistent. You boast of your love of liberty, your superior civilization . . . You hurl your anathemas [condemnations] at the crowned headed tyrants of Russia and Austria, and pride yourselves on your democratic institutions, while you yourselves consent to be the mere tools and bodyguards of the tyrants of Virginia and Carolina. You invite to your shores fugitives of oppression from abroad, honor them with banquets, greet them with ovations, cheer them, toast them, salute them, protect them . . . You profess to believe ‘that, of one blood, God made all nations of men to dwell on the face of all the earth’ . . . yet, you hold securely, in a bondage [a seventh part of the inhabitants of your country] which, according to your own Thomas Jefferson ‘is worse than ages of that which your fathers rose in rebellion to oppose’.”

The students will understand that Douglass contrasted the boasts of equality including in the Declaration of Independence that “‘all men are created equal’ yet (they) steal Black wages and deny the common ancestry of Adam that all men are of one blood.” “How do you interpret that quote from the Bible?” I asked. The students will conclude that a single origin for all humanity [Adam], which we now know to be African, proves the equality of all men. Finally, Douglass quotes Jefferson’s comments in his book, Notes on the State of Virginia, on the oppression of the enslaved as being worse than the so-called slavery of the Patriots to England.

The Constitution

If a student chooses the sentence containing “as it ought to be interpreted the Constitution is a glorious liberty document,” it is likely they will not agree with Douglass. Currently, almost all textbooks and historians contend that the Constitution is pro-slavery. Douglass’s interpretation is frankly a surprise for Americans even in 2023. The great abolitionist has been criticized for the latter statement by everyone from William Lloyd Garrison in the 1850s to Nicole Hannah-Jones in The 1619 Project, but his argument has a more complex basis that has not been brought to light except in the most recent academic monographs on abolitionism.

Douglass debated for more than two years until he became exhausted with his friend and ardent supporter, Gerrit Smith, whether there existed a morally justified position that the founders opposed slavery. In the oration he said, “if the Constitution were intended to be, by its framers and adopters, a slave-holding instrument, why neither slavery, slave holding, nor slave can anywhere be found in it.” Students might know that the words slave or slavery are never mentioned in the Constitution. Instead in the 3/5 Compromise slaves are called “other persons.” In the international slave trade compromise in Article I section 9, slaves are called “such persons.” Finally in the fugitive slave clause in Article 4 the escaped slave is called “no person.” Douglass was still hesitant in 1852 about this position as you can see when he continued, that the founders were not to blame for the apparent support of slavery “or at least so I believe.” But after such a long struggle he was relieved to be able to support a fight in the Congress (i.e., politically) and not just by “moral suasion,” as Garrison had taught. The Constitution, then, was not Garrison’s “covenant with death,” but became a “glorious liberty document” that he could use to fight for the freedom of his people.

Conclusion

“Fellow-citizens! I will not enlarge further on your national inconsistencies. The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretence, and your Christianity as a lie. It destroys your moral power abroad; it corrupts your politicians at home.

“How do you interpret that sentence?” I asked. The students will realize that Douglass is signaling he is coming to the end of the oration: he is ready to conclude. Here he lists the topics of the oration after the recital of the facts and ideas of the Revolution. At this point he adds one powerful metaphor relating to slavery that we have before encountered in the raging rivers and their dangerous floods in the introduction. Now these dangers have become one “horrible reptile…coiled up in your nation’s bosom; the venomous creature is nursing at the tender breast of your youthful republic; for the love of God, tear away, and fling from you the hideous monster, and let the weight of twenty millions crush and destroy it forever!” “How do you interpret this?” I asked. The students will realize that the twenty million was the northern majority. The undemocratic nature of the slave power is reminiscent of the white nationalist minority we are suffering from today in the arguments about abortion, the warming of the planet and the massive inequality to which our mainstream politicians are bowing today.

Here is where Douglass defends the founders as blameless, as above, for the pro-slavery Constitution, “at least, so I believe,” he maintained. “Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. ‘The arm of the Lord is not shortened,’ and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.” “How can you comment on this,” I ask. The students will remember that at the beginning Douglass, pointed out that the young country was only 76 years old in 1852. God’s arm is all powerful. “The arm of commerce has borne away the gates of the strong city. Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe. It makes its pathway over and under the sea, as well as on the earth. Wind, steam, and lightning are its chartered agents. Oceans no longer divide, but link nations together . . . Thoughts expressed on one side of the Atlantic are, distinctly heard on the other.”

The students will interpret these ideas as the familiar causes and effects of globalization. “Wind, steam, and lightning” are boats and telegrams. These are all causes of optimism the students will conclude.

“The fiat of the Almighty, ‘Let there be Light,’ has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the all-pervading light. The iron shoe, and crippled foot of China must be seen, in contrast with nature. Africa must rise and put on her yet unwoven garment. ‘Ethiopia shall stretch out her hand unto God.’” “Are there words here you do not know?” I ask. A fiat is a command. The passage also refers to foot-binding in China that ended only with the revolution in 1911, and Ethiopia is a reference to all of Africa and the effects of imperialism and racism. The very last part of the speech is a poem by William Lloyd Garrison who was Douglass’ teacher and mentor from early in his life as a free man. Here is an excerpt:

God speed the year of jubilee.

The wide world o’er

When from their galling chains set free

God speed the day when human blood

Shall cease to flow!

In every clime be understood,

The claims of human brotherhood,

And each return for evil, good.

“How would you interpret that?” I asked. Certainly, first of all the speech has been about freedom for the slaves, but second as a personal and political gesture Douglass showed his respect and admiration for Garrison even though their interpretations of the Constitution conflicted. Jubilee is the abolitionist term for emancipation which originated among the secular kings in the ancient holy land of the Hebrews as a 50-year celebration of forgiveness of slaves, debts, and debtors. There is a similar concession to Garrison’s leadership of the abolitionist movement when Douglass states his thesis later on.

The structure of the speech

Now that we are at the end of the speech, it is time to go back and figure out how Douglass put the speech together. Seeing the speech as a whole is a revelation for the students. After the rhetorical apologies at the very beginning, the speech proper begins: “This, for the purpose of this celebration, is the 4th of July” is near the top of the second column of the first page of the speech. The students have realized that he begins with a protest, it is the 5th. The first extended section is about the Revolution which comes after the context of the young nation and the hopes and dangers of rivers with their dual roles of fertility and flooding. His recounting of the floods includes power of the Red Sea. “How do you understand his reasoning?” I ask.

To begin with these stories, the students might say that he is clearly paying respect to the tradition of July 4th celebrations. But the great upheaval of 1776 was marked by patriotic sacrifice and brave action by the ancestors of the whites. There is a strong and dangerous undertow preceding the discussion of the Revolution. Douglass is setting a context unique to his purpose in the speech.

In the next section Douglass introduces his Thesis. He leads up to it from the first full paragraph on the left column of page 5 of the document. The thesis itself is on the bottom of the right column on page 6.

“My subject, then fellow-citizens, is American slavery . . . Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible, which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery—the great sin and shame of America!” It is a bold and dramatic period sentence. Next is his first quote from Garrison, his mentor. “I will not equivocate; I will not excuse.” This is one of the most famous lines from the great leader.

The optimism Douglass feels for the young country at the “impressible stage of its existence” only 76 years old at the beginning is always in conflict in the speech with the dangers of nature and the wrath of God against the Egyptians and Babylonians. Similarly at the end he describes his feeling of possibility for peace and abolition despite the “dark picture” he has painted. But this joy in the chances for change are abruptly flung aside as he describes the “horrible reptile . . . coiled up in your nation’s bosom,” of the “youthful” republic. However, again, the “arm of the Lord is not shortened” and change can be part of the work of history and if Americans “act in the living present.”

Douglass signals many of the sections by using the phrase, “My fellow citizens” or directly addressing his audience as “Americans.” He introduces the section on the Revolution with “Fellow-citizens.” He asks, “Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask why am I called upon to speak here today?” after the description of the Revolution to introduce the central conflict of the speech with Psalm 137 that identifies the oppression of the Jews during the Babylonian Captivity with his cause as a representative of the American slaves. We have quoted the thesis above that contains the same signal. Again, as he begins the topic of slavery: “Fellow-citizens; above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions!” right under the quote of Psalm 137. It is in this section that Douglass proves that the Slave is a Man despite his protestations to the contrary and then he describes the slave trade in Bringing Slavery Before the Eyes saying, “Behold the practical operation of this internal slave-trade.”

Finally, Douglass introduces his Summary and Conclusion going back to the very same call to attention. This time with a deeply sarcastic turn of phrase: “Fellow-citizens! I will not enlarge further on your national inconsistencies. The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretence, and your Christianity as a lie.”

This statement shows the power behind the ideas of systemic racism. The teacher is now prepared to take on the machinations of Ron DeSantis. The self-educated escaped slave puts the Governor’s inhumane and frankly ignorant ideas in the dustbin of history. Frederick Douglass oration, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” is a powerful antidote to DeSantis’ anti-woke bullying. Douglass’s descriptions make you feel their power. They will entrance your students and leave them ready to defend their values as learners and humanitarians. Douglass’ oration shows Ron DeSantis to be a man of limited intellectual force and a mean spirited and dangerous leader who acts with thoughtless abandon. His actions are the very definition of performative. He is an authoritarian poseur. In the face of Douglass’s oration DeSantis is shamed and outclassed.

I dedicate this this lesson to the brave students and educators who are in the classrooms fighting for the truth and complexity in the study of history. Remember that Frederick Douglass believed, “If there is no struggle, there is no progress.”