New Jersey Council for the Social Studies

Engaging High School Students in Global Civic Education Lessons in U.S. History

The relationship between the individual and the state is present in every country, society, and civilization. Relevant questions about individual liberty, civic engagement, government authority, equality and justice, and protection are important for every demographic group in the population. In your teaching of World History, consider the examples and questions provided below that should be familiar to students in the history of the United States with application to the experiences of others around the world.

These civic activities are designed to present civics in a global context as civic education happens in every country. The design is flexible regarding using one of the activities, allowing students to explore multiple activities in groups, and as a lesson for a substitute teacher. The lessons are free, although a donation to the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies is greatly appreciated. www.njcss.org

Era 6 The Emergence of Modern America: Progressive Reforms (1890–1930)

The development of the industrial United States is a transformational period in our history. The United States became more industrial, urban, and diverse during the last quarter of the 19th century. The use of fossil fuels for energy led to mechanized farming, railroads changed the way people traveled and transported raw materials and goods, the demand for labor saw one of the largest migrations in world history to America, and laissez-faire economics provided opportunities for wealth while increasing the divide between the poor and rich. During this period local governments were challenged to meet the needs of large populations in urban areas regarding their health, safety, and education.

Activity #1: The 20th Amendment and the Government of Israel

Read the information below from the constitutions of the United States and Israel on the election of the head of State and discuss the similarities and differences. Until the 20th Amendment was ratified, the United States did not have a designated date for the transfer of power from one elected leader to the next.

Twentieth Amendment

Section 1

The terms of the President and the Vice President shall end at noon on the 20th day of January, and the terms of Senators and Representatives at noon on the 3d day of January, of the years in which such terms would have ended if this article had not been ratified; and the terms of their successors shall then begin.

Section 2

The Congress shall assemble at least once in every year, and such meeting shall begin at noon on the 3d day of January, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.

Section 3

If, at the time fixed for the beginning of the term of the President, the President elect shall have died, the Vice President elect shall become President. If a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of his term, or if the President elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified; and the Congress may by law provide for the case wherein neither a President elect nor a Vice President elect shall have qualified, declaring who shall then act as President, or the manner in which one who is to act shall be selected, and such person shall act accordingly until a President or Vice President shall have qualified. (See the 25th Amendment, ratified on February 10, 1967)

Section 4

The Congress may by law provide for the case of the death of any of the persons from whom the House of Representatives may choose a President whenever the right of choice shall have devolved upon them, and for the case of the death of any of the persons from whom the Senate may choose a Vice President whenever the right of choice shall have devolved upon them. Ratified: January 23, 1933 (See the 25th Amendment, ratified on February 10, 1967)

BASIC LAW. THE PRESIDENT OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL (1964)

1. A President shall stand at the head of the State.

2.The place of residence of the President of the State shall be Jerusalem.

3.The President of the State shall be elected by the Knesset for seven years.The President will serve for one term only.

4.Every Israel national who is a resident of Israel is qualified to be a candidate for the office of President of the State.

5.The election of the President of the State shall be held not earlier than ninety days and not later than thirty days before the expiration of the period of tenure of the President in office. If the place of the President of the State falls vacant before the expiration of his period of tenure, the election shall be held within forty-five days from the day on which such place falls vacant. The Chairman of the Knesset, in consultation with the Vice-Chairmen, shall fix

the day of the election and shall notify it to all the members of the Knesset in writing at least three weeks in advance. If the day of the election does not fall in one of the session terms of the Knesset, the Chairman of the Knesset shall convene the Knesset for the election of the President of the State.

6. Proposal of Candidates (Amendment 8)

A proposal of a candidate for President of the State shall be submitted in writing to the Chairman of the Knesset, together with the consent of the candidate in writing, on the fourteenth day before the day of the election;

A member of the Knesset shall not sponsor the proposal of more than one candidate; A person that any ten or more members of the Knesset proposed his candidacy shall be candidate for President of the State, except if the number of sponsors decreased below ten because of the deletion of the name of a member of the Knesset as described in subsection (3);

Where a member of the Knesset sponsored the proposal of more than one candidate, the name of that member of the Knesset shall be deleted from the list of sponsors for all candidates he sponsored; Where the number of sponsors of a candidate decreased below ten because of the deletion of a name from the list of sponsors, a member of the Knesset who did not sponsor any proposal may add his name to the list of sponsors of that candidate, no later than eight days before the day of the election.

The Chairman of the Knesset shall notify all the members of the Knesset, in writing, not later than seven days before the day of the election, of every candidate proposed and of the names of the members of the Knesset who have proposed him and shall announce the candidates at the opening of the meeting at which the election is held.

7. The election of the President of the State shall be by secret ballot at a meeting of the Knesset assigned only for that purpose.

8.If there are two candidates or more, the candidate who has received the votes of a majority of the members of the Knesset is elected. If no candidate receives such a majority, a second ballot shall be held. At the second ballot only the two candidates who received the largest number of votes at the first ballot shall stand for election. The candidate who at the second ballot receives a majority of the votes of the members of the Knesset who take part in the voting and vote for one of the candidates is elected. If two candidates receive the same number of votes, voting shall be repeated.

If there is only one candidate, the ballot will be in favor or against him and he is elected if the number of votes in his favor outweighs the number of votes against him. If the number of votes in his favor equals the number of votes against him, a second ballot shall be held.

Questions:

1. What was the main problem the 20th Amendment solved? Was this a significant concern at the time?

2. How did the 20th Amendment solve that problem and what problems were not solved?

3. Should the United States consider amending the Constitution to provide for the election of the president and vice-president by the House and Senate?

4. Are the limitations or weaknesses in the way Israel is currently governed or is there system superior to others with popular elections?

Presidential Term and Succession

Date Changes for Presidency, Congress, and Succession

Interpretation and Debate of the 20th Amendment

Historical Background to the 20th Amendment

Democracy and Elections in Israel

Reforming the Israeli Electoral System

Activity #2: The Federal Communications Commission and the BBC in the United Kingdom

Regulating communications in the United States has been going on since the Radio Act of 1912. The military, emergency responders, police, and entertainment companies each wanted to get their signals out over the airwaves to the right audiences without interference. The Radio Act of 1912 helped to establish a commission that would designate which airwaves would be for public use and which airwaves would be reserved for the various commercial users who needed them.

In 1926, the Federal Radio Commission was established to help handle the growing complexities of the country’s radio needs. In 1934, Congress passed the Communications Act, which replaced the Federal Radio Commission with the Federal Communications Commission. The Communications Act also put telephone communications under the FCC’s control. The FCC broke up some of the communications monopolies, such as the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) which part of it became the American Broadcasting Company (ABC).

The FCC has been in the middle of controversial decisions. In 1948, the FCC put a freeze on awarding new television station licenses because the fast pace of licensing prior to 1948 had created conflicts with the signals. The freeze was only supposed to last a few months but was extended to four years.

The breakup of the telephone monopoly AT&T into a series of smaller companies is another example of a controversial decision. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 allowed competition by mandating that the major carriers allow new companies to lease services off of their lines and they could then sell those services to customers.

Another area where the FCC has been criticized is in regulating the content (“decency”) of radio and television broadcasts. There was an incident at the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show when the wardrobe of Janet Jackson malfunctioned, and part of her breast was exposed. The FCC does not set the content standards for movies but has the authority to issue fines.

Since 2014, the idea of “net neutrality” has been before the federal courts regarding an open and free internet and permission for providers to charge subscription fees.

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)

Daily broadcasting by the BBC began on November 14, 1922. John Reith was appointed as the director. There were no rules or standards to guide him. He began experimenting and published the Radio Times.

The BBC was established by Royal Charter as the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1927. Sir John Reith became the first Director-General. The Charter defined the BBC’s objectives, powers and obligations. It is mainly concerned with broad issues of policy, while the Director-General and senior staff are responsible for detailed fulfilment of that policy.

Questions:

- Is the regulation of radio, television, telephone and internet communications democratic?

- Should the freedom of speech be unlimited in the United States or does the government have the responsibility and authority to control the content and images?

- Do the Regulatory Agencies of the United States promote the general welfare, or do they restrict the blessings of liberty?

- Are monopolies in the communications and technology industries justified because of the expense and protection of patents?

- Does the United Kingdom have a state sponsored news media in the BBC?

- Which country’s policies on communications do you agree with? Why?

BBC Guidelines for Inappropriate Content

The Communications Act of 1934

History of the Federal Communications Commission

Activity #3: The Panama Canal Crisis (1903) and the Suez Canal Crisis (1953).

Suez Canal Crisis (1956)

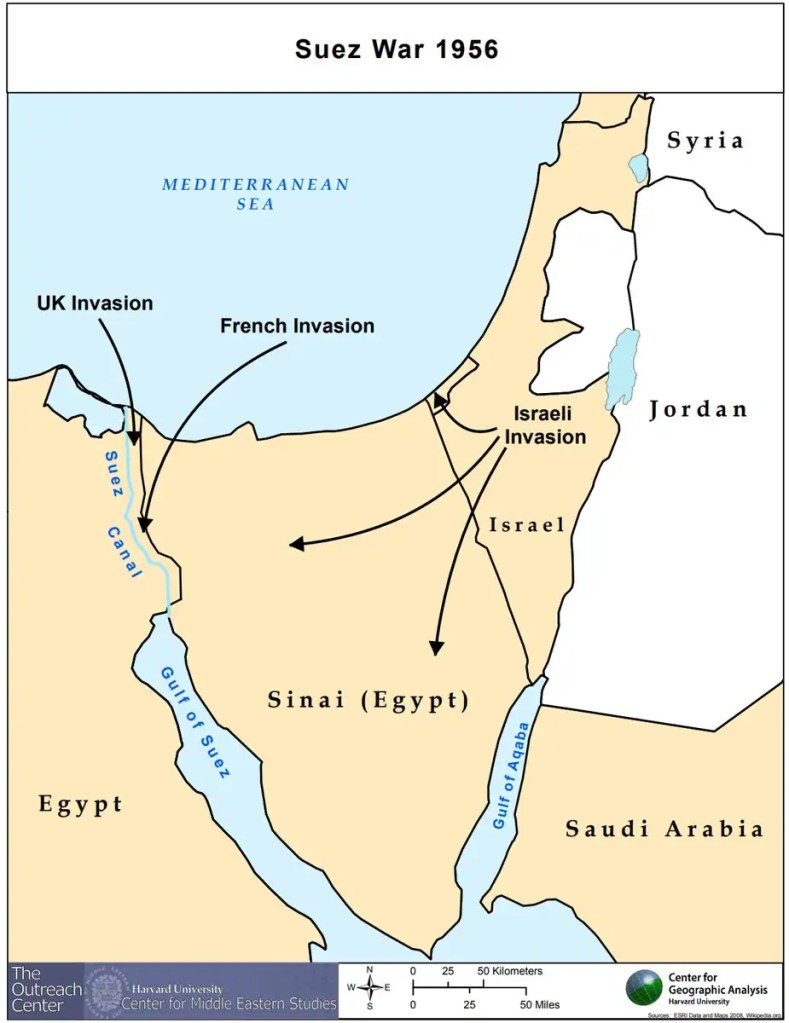

On July 26, 1956, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser announced the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, which was jointly operated by a British and French company since its construction in 1869. The British and French held secret military consultations with Israel, who regarded Nasser as a threat to its security. Israeli forces attacked Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula on October 29, 1956, advancing to within 10 miles of the Suez Canal. Britain and France landed troops of their own a few days later.

The relations between the United States and Britain weakened when Britain bombed Egypt over their blockade of the Suez Canal. The United Nations threatened Britain with sanctions if there were any civilian casualties. This led to economic panic and Britain faced having to devalue its currency. President Eisenhower was shocked that he was not informed of the British military response and put pressure on the International Monetary Fund to deny Britain any financial assistance. The British reluctantly accepted a UN proposed ceasefire. Under Resolution 1001 on 7 November 1956 the United Nations deployed an emergency force (UNEF) of peacekeepers into Egypt.

The canal was closed to traffic for five months by ships sunk by the Egyptians during the operations. British access to fuel and oil became limited and resulted in shortages. Egypt maintained control of the canal with the support of the United Nations and the United States. Under huge domestic pressure and suffering ill-health Eden resigned in January 1957, less than two years after becoming prime minister.

Questions:

- Does the United States have a responsibility to support its allies even when our policies do not agree with their policies or actions?

- Did President Eisenhower overstep his authority by asking for economic sanctions against Britain?

- Did President Roosevelt overstep his constitutional authority in signing the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty or was the overstep committed by the Philip Bunau-Varilla, Panama’s ambassador to the United States?

- In matters of foreign policy, do economic interests justify military actions?

International Law and the Panama Canal

Why was the Suez Canal Crisis Important?

Activity #4: Poll Taxes in the USA and the Voting Petitions of the Chartist Movement in the United Kingdom

Poll Taxes and the 24th Amendment

The US Constitution leaves voter qualifications, except for age, to individual states. By the mid-19th century, however, most states did not limit voting by property ownership or poll taxes. A poll tax of $2 in 1962 would convert to approximately $17 in 2020 dollars. After the ratification of the 15th Amendment, in an attempt to limit Black voter registration and turnout, many states re-established poll taxes. The combination of poll taxes, literacy tests, White primaries (permitting only Whites to vote in primary elections), intimidation, violence, and disqualification of people convicted of felonies succeeded in reducing voter participation.

In his 1962 State of the Union Address, President Kennedy put the issue on the national agenda when he called for the elimination of poll taxes and literacy tests, stating that voting rights “should no longer be denied through such arbitrary devices on a local level.” The proposal to ban literacy tests did not make it past a Senate filibuster, but after debating the substance of the proposal to end the poll tax and whether or not the tax should be eliminated by a Constitutional amendment, Congress passed the 24th Amendment, abolishing poll taxes in federal elections on August 27, 1962.

The passage of the 24th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 did not completely eliminate the obstacles for voter registration or voting. On March 24, 1966, the Supreme Court ruled in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections that poll taxes could not be collected in any election, including state and local elections, since they violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. The 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote but enforcement is dependent on congressional legislation. To what extent are citizens denied the right to vote today?

Chartist Movement in the United Kingdom

In 1838 a People’s Charter was drawn up for the London Working Men’s Association (LWMA) by William Lovett and Francis Place, two self-educated radicals, in consultation with other members of LWMA. The Charter had six demands:

All men to have the vote (universal manhood suffrage)

Voting should take place by secret ballot.

Parliamentary elections every year, not once every five years

Constituencies should be of equal size.

Members of Parliament should be paid.

The property qualification for becoming a Member of Parliament should be abolished.

The Chartists’ petition was presented to the House of Commons with over 1.25 million signatures. It was rejected by Parliament. This provoked unrest which was swiftly crushed by the authorities. A second petition was presented in May 1842, signed by over three million people but again it was rejected, and further unrest and arrests followed. In April 1848 a third and final petition was presented. The third petition was also rejected but there were no protests. Why did this movement fail to complete its objectives?

Questions:

- Should the requirement of having a birth certificate or another state ID document as proof of residency a modern-day poll tax? In all states these documents have a cost.

- Does the Voting Rights Act of 1965 need to be updated with the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement act?

- Was the poll tax a financial burden on a low-income family? (In today’s currency about $34 for two adults)

- What led to the rise of the Chartists Movement?

- Why did the Chartist Movement fail to achieve its objectives?

- With the many criticisms of a democracy and a republic, is it the preferred form of government?

Barriers to Voting: Poll Taxes

Abolition of Poll Taxes: 24th Amendment

Voting Rights for African Americans