My Story: Rev. Samson Occum, 1787 Mercer County

Visit of Rev. Samson Occum to the Lenape at New Stockbridge

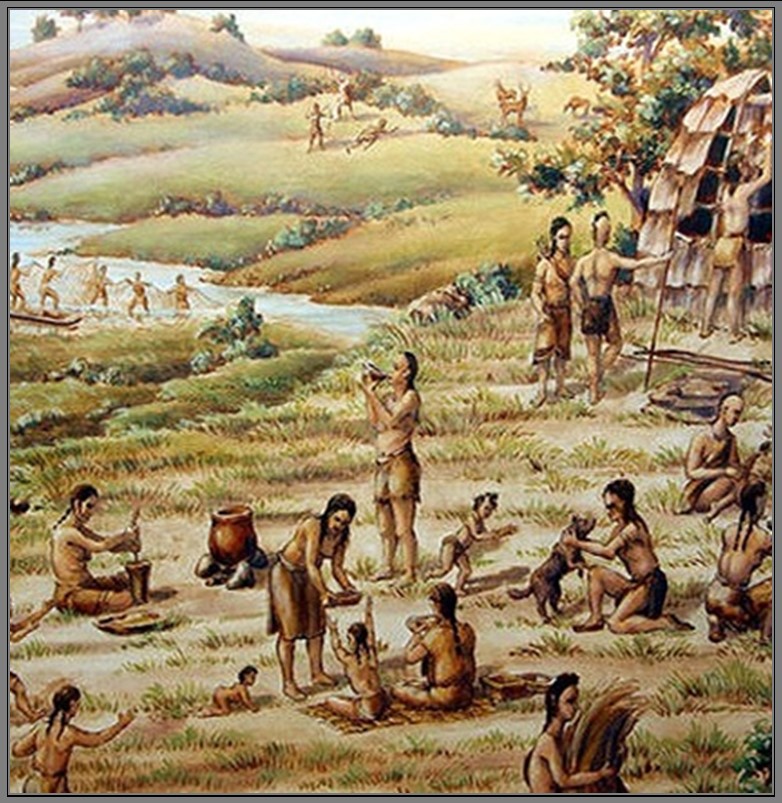

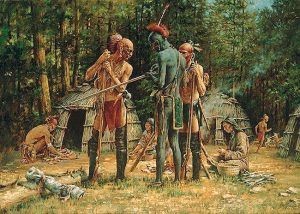

Samson Occum, leader of the New England Brothertown religious movement (not to be confused with the NJ Brotherton community), had a long association with the Delaware Indians. After his time as Eleazar Wheelock’s first Indian pupil, Occum became a minister. Based upon his success in religious education, Wheelock began his Indian School in Connecticut, where his first two pupils were Delaware Indian boys from John Brainerd’s Bethel Mission settlement in present-day Monroe Township, New Jersey. The Delaware (Lenape) supported the French in the French and Indian War and by 1777, many had left New Jersey for areas of New York and western Connecticut. By 1802, the assimilation with the Allegheny and Oneida was complete. (See The Brotherton Indians of New Jersey, 1780)

Use the documents below to discuss and investigate the following questions:

- What motivated Samson Occum to become involved with Native Americans?

- How did decisions affect the livelihood of the Lenape and Delaware Valley Indians?

- Was New Stockbridge a suitable place for the migration of the Lenape and other native Americans?

- Do you think the travels of Rev. Samson Occum were planned in advance or were they a response to the letter from the Native Americans at New Stockbridge dated Nov. 28, 1787.

- What was traveling in New Jersey like for Rev. Occum (or anyone)?

- Comment on five days in Rev. Occum’s journal.

The following information details Occum’s visit to Brotherton and Weekping (Coaxen):

From Love’s Life of Occom (p. 276):

Fundraising mission of Samson Occom and others to New York, New Jersey & Pennsylvania:

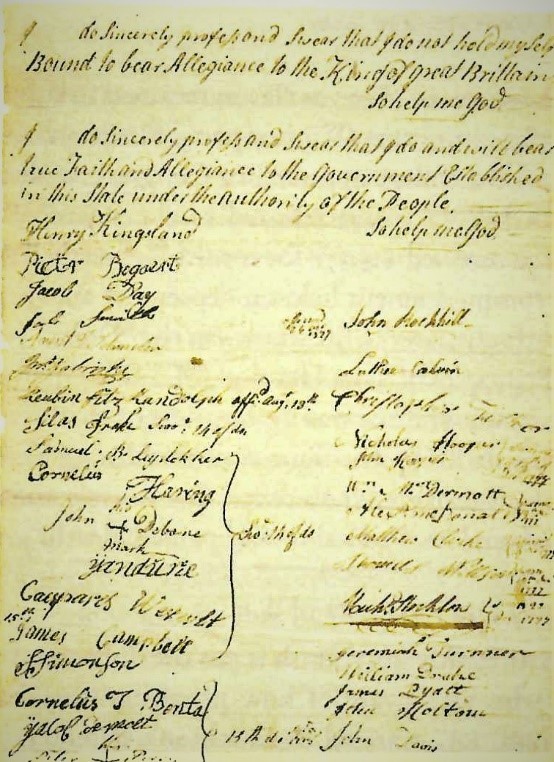

November 28, 1787 (underlining is for emphasis)

To all Benevolent Gentlemen, to Whom these following lines may make their appearance.

We who lately mov’d from Several Tribes of Indians in New England, and Setled (sic) here in Oneida Country. And we also Muhheeconnuck Tribe, who lately came from Housotonuk alias Stockbridge, and have settled in Oneida, And finding it our indispensible (sic) Duty to maintain the Christian Religion amongst ourselves in our Towns, And from this Consideration, Some of us desired our Dear Brother, the Rev d Samson Occom, to give us a visit, and accordingly, he came up two years ago this Fall, and he was here a few Days; and his preaching came with great weight upon our Minds. And he has been here two Summers and Falls since. And we must confess to the Glory of God, that God has made him an Eminant (sic) Instrument amongst us, of a Great and Remarkable Reformation. And have now given him a Call to Settle amongst us, and be our Minister that we may enjoy the glorious Doctrines and ordinances of the New Testament.

And he has accepted our Call. But we for ourselves very weak, we c’d do but very little for him. And we want to have him live comfortable.

The late unhappy wars have Stript (sic) us almost Naked of everything, our Temporal enjoyments are greatly lesstened (sic), our Numbers vastly diminished, by being warmly engaged in favour of the United States. Tho’ we had no immediate Business with it, and our Spiritual enjoyments and Priviledges (sic) are all gone. The Fountains abroad, that use to water and refresh our Wilderness are all Dryed up, and the Springs that use to rise near are ceased. And we are truly like the man that fell among Thieves, that was Stript (sic), wounded and left half dead in the high way. And our Wheat was blasted and our Corn and Beans were Frost bitten and kill’d this year. And our moving up here was expensive and these have brought us to great Necessity And these things have brought us to a resolution to try to get a little help from the People of God, for the present; for we have determined to be independent as fast as we can, that we may be no longer troublesome to our good Friends, And therefore our most humble Request and Petition is, to the Friends of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ, [that they] would take notice of us, and help us in encourageing (sic) our Dear Minister, in Communicating Such Things that may Support him and his Family. This is the most humble request and Petition of the Publicks (sic) true Friend & Brothers

ELIJAH WIMPEY

DAVID FOWLER

JOSEPH SHAUQUETHGENT

HENDRECH AUPAUMUT

JOSEPH QUAUNCKHAM

PETER POHQUENUMPEC

New-Stockbridge (NY)

Novr 28: 1787

Native Americans from Stockbridge, MA moved to this location during the American Revolution. The Stockbridge, refuges of tribes mainly of adjoining New York that had settled in the “prayer town” of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, accepted an invitation of the Oneidas to live and share on their reservation in New York. Stockbridge, NY was incorporated in 1791.

Brotherton, Novr 29: 1787.

Conn. Hist. Soc., Indian Papers

A journal of the daily travel of the Rev. Samson Occom in New Jersey

From Occom’s Journal – portions of above-referenced trip [edited by RW for clarity].

December 28, 1787: New Windsor, New York

December 29, 1787: Mr. Brewsters at Blooming Grove; Robinsons Tavern; Florida (NY)

December 30, 1787: Warwick (NY)

December 31, 1787: Mr. Smith’s Public House

January 1, 1788: To Rev. Baldwin’s house and lodged.

January 2, 1788: Went to Parsippany to Mr. Grovers and then back towards Rev. Baldwin.

January 3, 1788: In same area.

January 4, 1788: Called at Rev. Green’s and then went to Mr. Chapmans at Newark mountains [Jebediah Chapman was the master of the Orange Dale Academy. In 1790, Occom sent New Stockbridge resident John Quinney to the Academy.] Went to Crain’s Town and lodged with at Mr. Crain’s.

January 5, 1788: Set off for Horse Neck and put up at Esq. Crain’s. (Horse Neck Tract is present day Caldwell, Fairfield, Verona, Cedar Grove, and Essex Fells.)

January 6, 1788: After meeting, went on about three or four miles and lodged there.

January 7, 1788: Towards Morristown, stopped at Mr. Grover’s and later lodged at Morristown.

January 8, 1788: Went to Basking Ridge and attended the funeral of Rev. Canada’s daughter.

January 9, 1788: Got to Mill Stone and put up at a tavern.

January 10, 1788: At noon, arrived at Dr. Witherspoon’s house at Prince Town. Left and traveled to Black Horse Tavern (Columbus, Burlington County, New Jersey).

January 11, 1788: After eating, went on again. Got to Quakson towards night where there were three or four families of Indians, we called in at one, and they appeared extremely poor, so we went on and put up at a tavern [Red Lion?]. It was cold and we set up long and I was ill with a cold and cough.

January 12, 1788: After breakfast, set off again and got to Agepelack [Edgepillock] some time before night. Stopped and stayed at Friend Mytop’s house. I was very poor with my cold and coughed much.

Sabbath, January 13, 1788: Felt a little better and about 11 went to meeting, and there was not many people they had but little notice. I spoke from the Words, that which is wanting &c and the people attended well. After the service I went home with Daniel Simon to his mother-in-laws house [Widow Calvin] and stayed there all the week. Daniel Simon lost an only child this week and I preached a funeral discourse from the Words Set thy House &c and we had singing meetings every night, and prayed with them and gave them a word of exhortation.

Sabbath, January 20, 1788: Preached here again and it was very bad traveling, and there was a considerable number of people collected, and I spoke from [ ] and the people attended well, and after the meeting went back to Widow Calvin’s [widow of Stephen Calvin, son-in-law of Weequehela] and in the evening people came together and we had an exercise with Christian cards and we sang and prayed and it was a solemn time. Many were affected, and the people were very loath to leave the place & they stayed late.

January 21, 1788: We were up early and got ready as soon as we could. We took leave of the family and others came to take leave of us, and so we directed our course to Philadelphia and in the evening we got to the river against the City and we put up in a tavern one Friend Cooper.

February 22, 1788: About 10 we left Philadelphia and it was bad crossing the river. We went on ice most of the way over, and it was a cold day, and in the evening we got to Moorestown and Brother David [David Fowler] was sick, & Peter [Pauquunnuppeet] went [to] Agepelack, and dined and lodged in a tavern.

February 23, 1788: I went to Quakson [Coaxen] and left David very sick [at Moorestown] and got there before noon, and put up at a public house. In the afternoon, went to an Indian house, and towards night went to a public house.

February 24, 1788: About 11 went to meeting to a meeting house which Mr. John Brainerd used to preach to a number of Indians and there was considerable [number] of people and I spoke from Acts XI.26 and some time towards night, we went to Mount Holly, got there near sun set and we put up at Dr. Ross and David was very sick, and here we stayed some days, and I preached four times in this place. (Acts 11:26 – “Then Barnabas went to Tarsus to look for Saul, and when he found him, he brought him to Antioch. So for a whole year Barnabas and Saul met with the church and taught great numbers of people. The disciples were call Christians first at Antioch.”)

February 29, 1788: I left Mount Holly and left David there as he was not well enough to set out. I got to Trenton in the evening. Called on Rev. Armstrong, but he was not home, so I went to a public house.

March 1, 1788: Went back to Bordentown.

March 2, 1788: Preached at Bordentown, went back to Trenton.

March 3, 1788: Went to the meeting house at Trenton and there were considerable people. In the afternoon, I went back to the Draw Bridge (at Bordentown) and had an evening meeting with a vast number of people.

March 4, 1788: David and I set off pretty early and we got to [ ] and lodged at Dutch Tavern.

March 5, 1788: Went to New Brunswick. David left a bundle and had to go back. At New Brunswick, went to see Rev. Munteeth, and then to Dr. Scott. At Dr. Scott’s, Peter was found; he had been straggling about a fortnight. In the evening there was a society and I spoke a few words by way of exhortation. Afterwards, we returned to Dr. Scott’s, where we lodged.

March 6, 1788: Visited several houses, and preached at the Presbyterian church. There was a large number of people. I lodged at Dr. Scott’s and David and Peter lodged in another house.