How Ike Led

The Principles Behind Eisenhower’s Biggest Decisions

By Susan Eisenhower

Reviewed by Hank Bitten

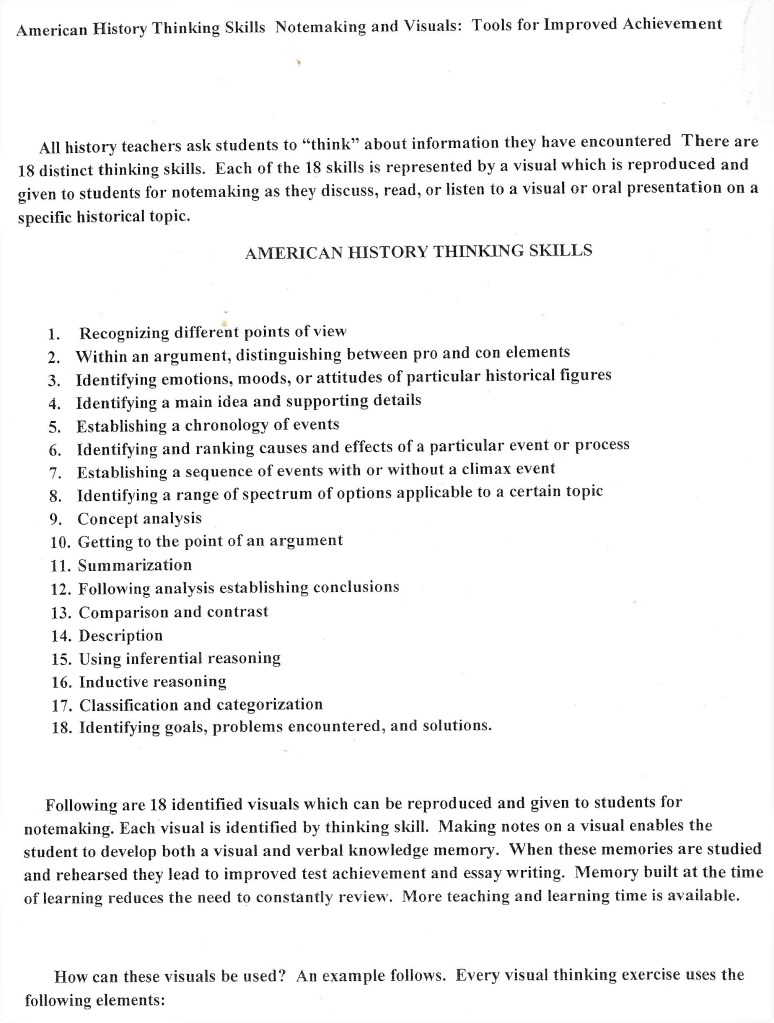

Having taught 20th century United States’ history for over 30 years, I regret to say that the Eisenhower administration is overshadowed by thematic events relating to the Cold War and civil rights over several decades. In this book published by President Eisenhower’s granddaughter, Susan, who is the daughter of John Eisenhower, there are lessons to be learned and analyzed from the 1950s that are connected to our most recent current events and dialogue.

For example:

Negotiating with a divided Congress

Appointments that would influence the future direction of the Supreme Court

Presence of extremist groups

Racial and social injustices

Health of the President

Competitive views over a balanced federal budget v. large deficits

Fake news or disinformation

Vice-President who could become president or run in a future election

How Ike Led is a book that should be of interest to high school and college students and every social studies teacher. The book offers fresh perspectives from the memories of Ike’s teenage granddaughter and comprehensive interviews with living members of his administration and historians. I admired President Eisenhower as my ‘first’ president during my elementary school years in part because of his

popularity with my parents, especially my father who served in World War II. I also followed President Eisenhower’s policies closely as we debated and discussed them in the context of President Kennedy’s New Frontier.

As a teacher, I taught my students the significance of Eisenhower’s decisions on the interstate highway system, building natural gas pipelines across America, the St. Lawrence Seaway, admission of Alaska and Hawaii as states, his leadership in the Suez Canal crisis, bringing America into the competitive space race, and the historic ‘kitchen summit meeting’ and visit of Nikita Khrushchev to Eisenhower’s Gettysburg home.

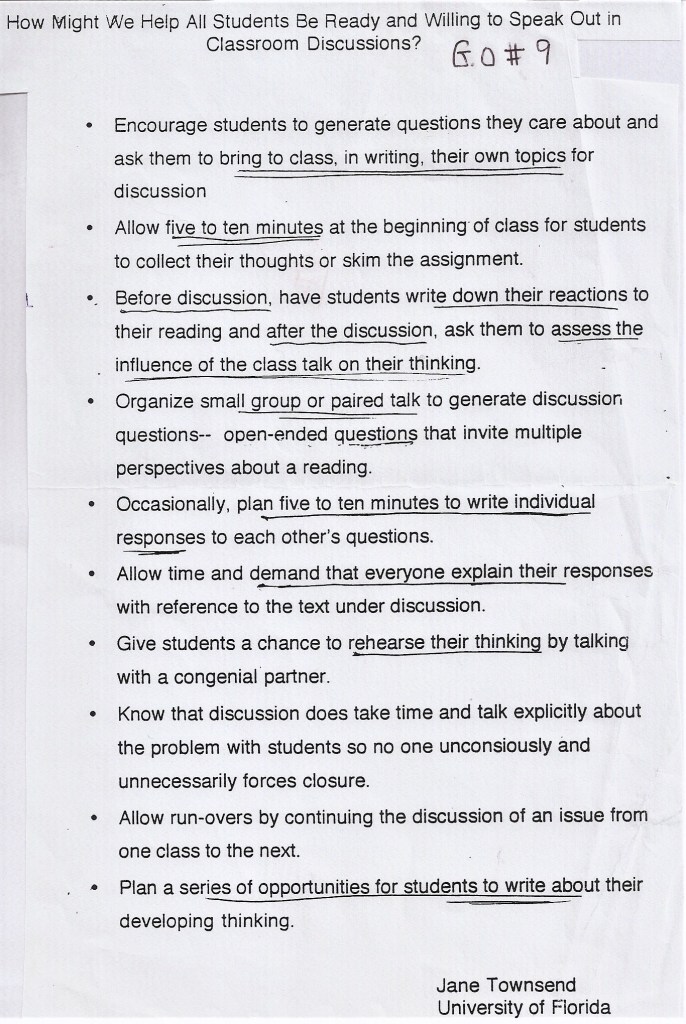

An interesting comparison with President Trump is for students to develop a thesis (or a Claim) regarding how historians have judged the success of presidents who never held an elected office before becoming president. These are General Zachary Taylor, General Ulysses S. Grant, Herbert Hoover, General Dwight Eisenhower, and Donald Trump. President Trump is the sole exception in this group with no prior military or appointed government service. Ask your students to test the claim if political experience in an elected office is necessary for presidential leadership?

The book is organized into sixteen chapters with eleven chapters dedicated to analyzing the principles and decisions of President Eisenhower. I encourage you and your students to read the whole book as this review will focus on McCarthy, civil rights, and the space race.

With the election of President Eisenhower, the first Republican elected president since Herbert Hoover 25 years before, the Republicans were concerned about one political party dominating the legislative and executive branches for more than two decades. The unexpected defeat of Governor Thomas Dewey (NY) in 1948 amplified these concerns. The ratification of term limits in the 22nd Amendment was one

attempt to prevent a repeat of the unprecedented four terms of FDR by protecting the legacy of our competitive democracy.

In the first weeks following Eisenhower’s inauguration, Joseph Stalin died on March 5, 1953 creating uncertainty in the stability of the world’s second nuclear power. In his first year, Eisenhower negotiated a ceasefire with the Communists of North Korea, implemented a system of cost-benefit analysis to control military spending, and advocated for the expansion of social security to ten million new workers

with substantial increases in their benefits. These decisions were criticized by the right wing of the Republican Party who feared Eisenhower’s inexperience as a politician and the consequences of transferring the savings from defense to domestic priorities.

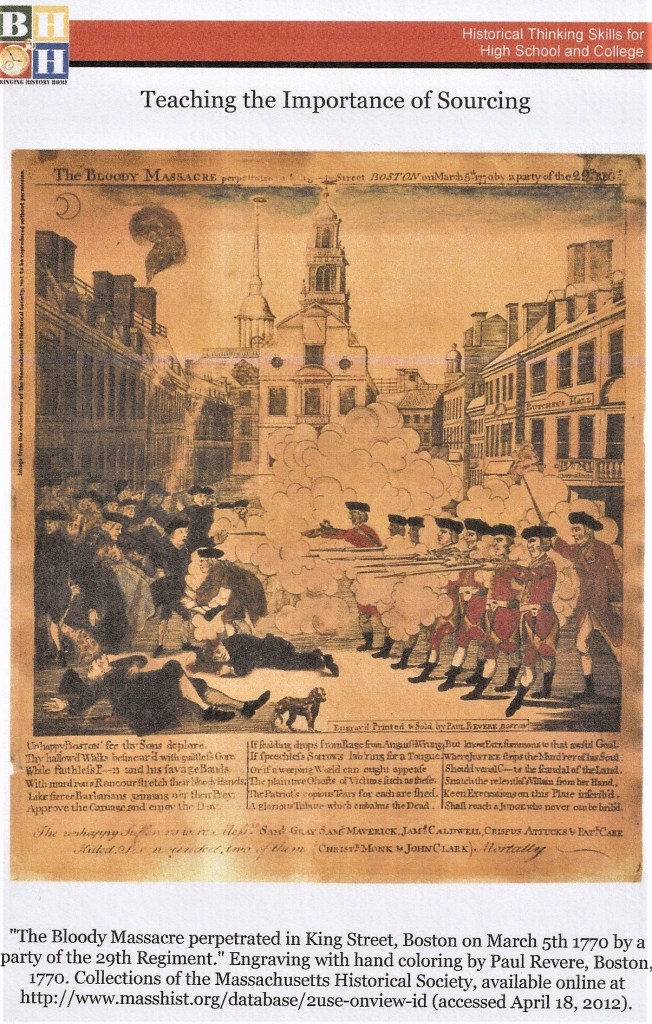

The New Republic (10/2/2020)

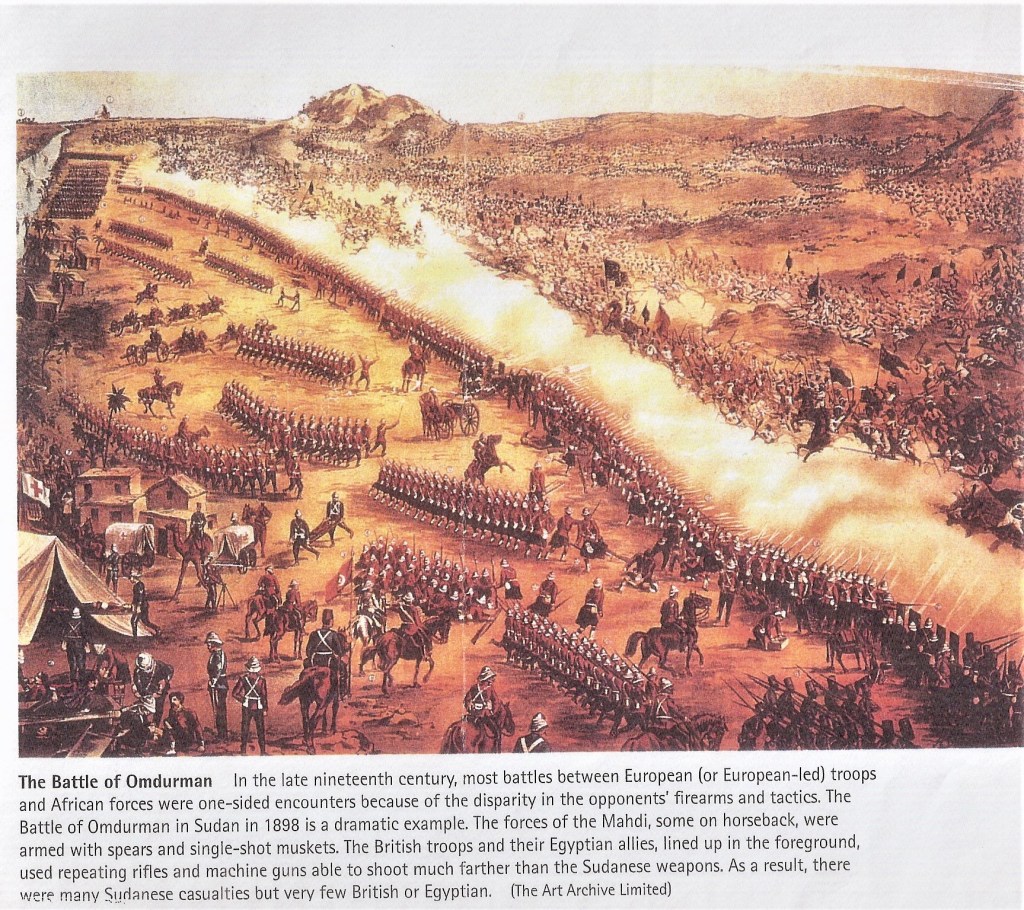

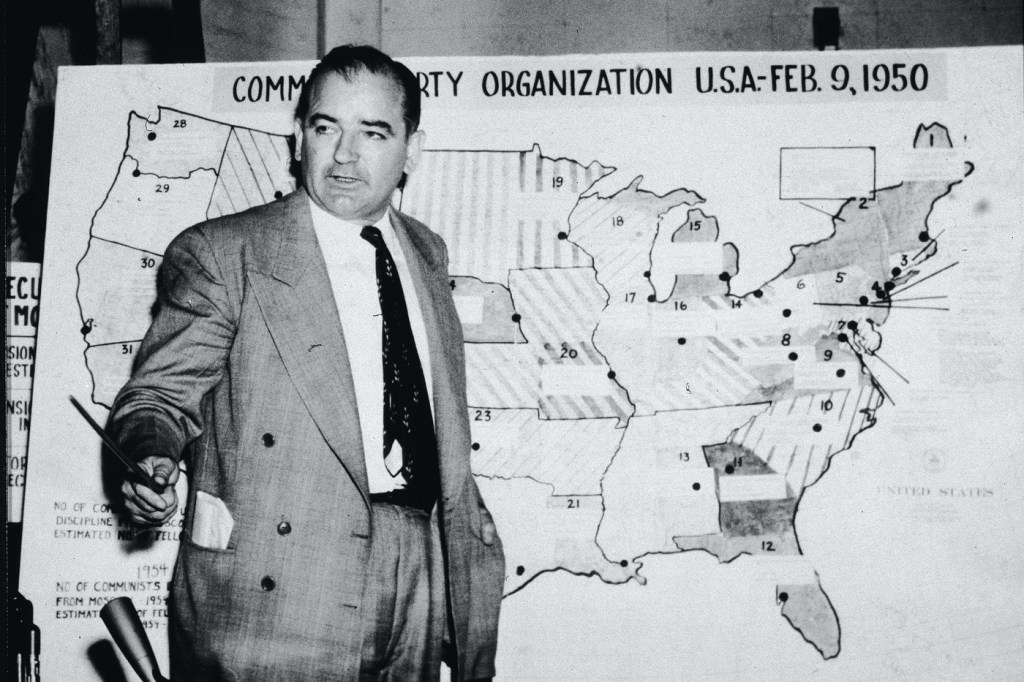

Teaching the Cold War from 1946-1989 is challenging for teachers because every major event (Eastern Europe, Berlin, Fall of China, Korea, displaced persons, Marshall Plan, missile gap, Cuba, Southeast Asia, Middle East, space race, summit meetings, and Afghanistan) require more than the approximate three weeks or 15

days permitted in a traditional U.S. History course. The insights by Susan Eisenhower provide a perspective for a unit or series of lessons with students determining the effectiveness of President Eisenhower’s decisions regarding the televised McCarthy Hearings of April – June 1954.

For example…

1. How should President Eisenhower respond to Senator McCarthy’s criticism of Charles (Chip) Bohlen as ambassador to the Soviet Union?

2. How should President Eisenhower respond to the undocumented attack of disloyalty against Ralph Bunche, a distinguished African-American diplomat at the United Nations and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950?

3. How can President Eisenhower advance his agenda in a divided Senate with 48 Republicans, 47 Democrats, and 1 Independent? (President Eisenhower needed every Republican vote, including the support of Senator McCarthy but in July 1953, Senators Tobey (NH) and Taft (OH) died. Senator Taft was replaced by a Democrat.)

4. How should President Eisenhower respond to the passage of the Bricker Amendment (Senator Bricker is a Republican from Ohio) regarding the limitations of the president to make agreements with foreign governments?

5. How should President Eisenhower respond to the report that the Soviet Union allocated millions of dollars to the American Communist Party to interfere in our government? (Venona Project)

6. How should President Eisenhower respond to Senator McCarthy’s directive to federal workers to “disregard presidential orders and laws and report directly to him on graft, corruption, Communism and treason?”

In cooperative groups, representing different perspectives (i.e. State Department, National Security Council, Mamie and Eisenhower’s brothers, Think Tank, Members of the House, Members of the Senate, CIA, journalists, etc.) discuss the options below and make recommendations to President Eisenhower on the six questions above.

Options to Consider:

a. Work behind the scenes with moderate members of Congress

b. Make public announcements criticizing Senator McCarthy’s public hearings

c. Be patient and quiet

d. Direct the Attorney General or FBI to investigate Senator McCarthy

e. Support the hearings and investigations to win support of the conservative Republicans

President Eisenhower chose the option to remain patient and quiet. He understood Senator McCarthy as one who desired to be the center of public attention and that in the course of the hearings, he would likely make mistakes. Throughout the book, Susan Eisenhower, an accomplished author, policy strategist, and historian, offers her own interpretations, which students can use as the basis of their “claim” or argument and research evidence to support or reject it. For example, “He had the power over the thing McCarthy had most deeply desired – to engage Eisenhower in this circus, thus legitimatizing his own status as an important leader while raising himself and his shameful shenanigans to the level of a coequal branch of government.” (p. 201) Consider having your students discuss or debate the validity of her “claim.”

Civil Rights

Historians are divided on President Eisenhower’s record on civil rights. Many teachers only focus on school integration with Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka KS and Little Rock, AK. President Eisenhower’s record on civil rights provides students with an opportunity for inquiry, research, and evidence based arguments. Consider the important personal information on President Eisenhower’s character and support for African Americans from his youth through his presidency as provided by Susan Eisenhower.

Abilene High School was integrated when Ike attended it (1905-1909). He was the only football player on his team to shake hands with an African American player from an opposing team. As a military leader in World War II, Ike insisted that the blood supply be integrated and when Australia refused to allow the black division Eisenhower deployed after Pearl Harbor, he rescinded the order. He also supported the desegregation of schools in Washington D.C. and appointed E. Frederic Morrow (from Hackensack, NJ and Rutgers Law School) to his personal staff and J. Ernest Wilkins Sr. as Assistant Secretary of Labor.

In considering evidence about President Eisenhower’s record on civil rights, students should research evidence regarding the record of American presidents from Teddy Roosevelt to Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Students might also research the records of Eleanor Roosevelt and both black and white leaders during the civil rights period of 1900-1960. On September 24, 1957, President Eisenhower made one of the most controversial decisions of the 20th

century which could have devastating consequences for him and the United States.

In the context of the questions the United States is facing today about race, equality, policing, criminal justice, education, and opportunity, the leadership role of President Eisenhower is worth analysis by students. On this date, President Eisenhower announced the first imposition of federal troops in the South since Reconstruction (90 years before). He deployed 500 troops from the famed 101st Airborne paratroopers who landed on Normandy in 1944. (p. 244) This was in response to the deployment of the Arkansas National Guard a few days earlier by Gov. Oval Faubus to “preserve peace and good order by preventing the integration of nine African American students into Little Rock High School. (Listen to Eisenhower’s 12 minute Address to the American people and visit the sequence of online documents on this decision at the Eisenhower Library) Senators and governors threatened to cut funds for public schools, Senator Olin Johnston (D-SC) called for a state of insurrection, President Eisenhower was accused of being a military dictator, the Southern Manifesto was signed by 12 senators and 39 congressmen, and violence and lynching of innocent black Americans increased.

The leadership of President Eisenhower was further challenged in the federal courts when the Little Rock Board of Education petitioned the Eastern District Court of Arkansas on February 20, 1958 to “postpone the desegregation efforts because of chaos, bedlam and turmoil in the community.” (p. 260)

The Court agreed to a 21/2 year postponement of preventing black students from attending Little Rock High School. On September 12, 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Cooper v. Aaron in favor of desegregation. The decision was unanimous and personally signed by each of the nine justices! The decision was transformational in the education of students in the United States of America! The Doll Experiment by psychologist Dr. Kenneth B. Clark provides a powerful vision of the effects of racial

discrimination.

Susan Eisenhower also included the letter from the parents of the nine black students who entered Little Rock H.S. in her book. The letter speaks volumes about human and civil rights as does the interview by Oprah Winfrey with the Little Rock Nine in 1996. (September 30, 1957)

“We the parents of nine Negro children enrolled at Little Rock Central High School want you to know that your action in safeguarding their rights have strengthened our faith in democracy. Now as never before we have an abiding feeling of belonging and purposefulness. We believe that freedom and equality with which all men are endowed at birth can be maintained only through freedom and equality of opportunity for self-development, growth and purposeful citizenship.

We believe that the degree to which people everywhere realize and accept this concept will determine in a large measure American true growth and true greatness. You have demonstrated admirably to us, the nation and the world how profoundly you believe in this concept. For this we are deeply grateful and respectfully extend to you our heartfelt and lasting thanks. May the Almighty and all wise Father of us all bless guide and keep you always….” (p. 259)

President Eisenhower replied to this letter on October 4. In the context of President Eisenhower’s decisions on civil rights and Little Rock, how will your students

analyze his record? While Eisenhower is pledging his support for the rule of law in the desegregation of schools, why was he reserved in the civil rights and voting rights legislation he proposed in his 1956 State of the Union address? Will your students evaluate President Eisenhower as a proactive leader to end the violence and discrimination against black Americans or will they decide that his reserved approach continued to deny 75% of African American citizens the right to vote?

Space Race

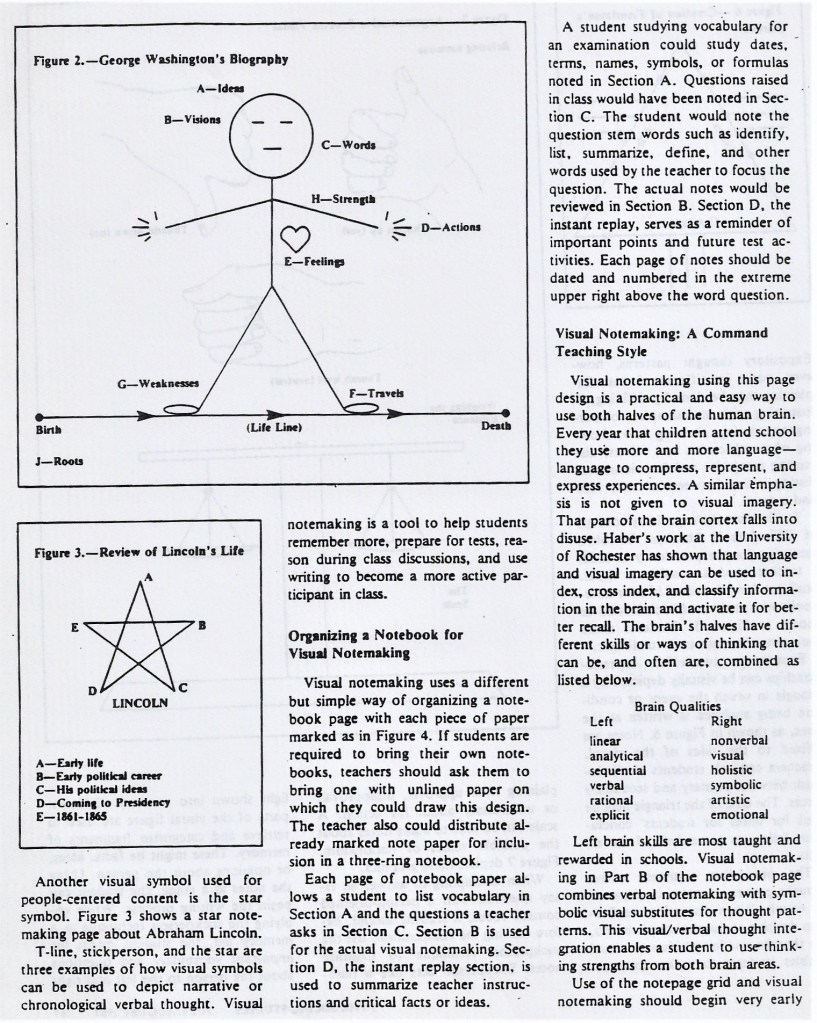

The story of NASA and the transition to the private enterprise of space is slowly evolving into our curriculum as it competes with complex domestic and foreign policy issues in the first two decades of the 21st century. The development of technology, space exploration, military technology, cybersecurity, and the impacts on climate are embedded within the performance expectations of social studies curriculum and the C3 Framework. The United States put its first satellite (Explorer 1) into space on January 31, 1958 and six weeks later on March 17, it launched its first solar powered satellite into orbit.

Composite illustration assembled from static display of satellite, Earth from orbit and telescope photo of stars. Science Hi Blog

President Eisenhower’s administration laid the foundation for the freedom of space, the peaceful pursuit of scientific research on the continent of Antarctica, the Alliance for Progress, the innovative technology of the U-2 reconnaissance program, Nautilus missiles, and civil defense. These initiatives proved to be game-changers for America’s leadership at a time when balanced budgets were considered essential to the security of the United States.

In the middle of these significant initiatives in a divided Congress, Senator John F. Kennedy made a speech in the U.S. Senate on August 14, 1958 calling attention to the ‘missile gap.’

“In 1958, Sen. John F. Kennedy, without access to classified information, and relying only on public sources, was persuaded by Joe Alsop, a Georgetown neighbor and social friend, to make a speech on the floor of the Senate. It was there that Kennedy used the term “missile gap” for the first time, an expression that was a ringing indictment of Eisenhower’s budget conscious ways, accusing him of failing to provide adequate security for the United States. In his speech Kennedy asserted that the Soviet Union could destroy ’85 percent of our industry, 43 of our 53 largest cities, and most of the Nation’s population.” (p. 287) Kennedy’s Speech on Missile Gap

History would reveal during the Kennedy administration that there was no missile gap. Actually, the United States had 160 operational Atlas ICBMs to six in the Soviet arsenal! (p. 301) The information in this book provides an opportunity for teaching students the skills of searching for credible evidence.

Students need to research maps, photographs and census data in addition to primary and secondary source documents. This takes time, patience, perseverance, and guidance in searching for factual information in multiple locations, organizing information, engaging in rigorous analysis and providing complete documentation.

In conclusion, teachers might ask their students what lessons we can learn from the leadership style of Dwight David Eisenhower during what our textbooks call the decade of the military industrial complex. Susan Eisenhower writes, “The measure of a leader is more than the sum of his or her successful decisions: qualities of character, including empathy and fairness, are also central to any person worthy of that status.” (p. 307)

In answering this question, students might ask if President Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon were leaders of this paradigm, if the presidents in their lifetime meet this standard (Presidents Obama and Trump), and to what extent local leaders in school, government, and business are leaders who meet it.