Lesson Based on the Movie Glory

John Staudt

“Let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” – Frederick Douglass

Assignment:

- Read the packet prior to our class viewing of the Edward Zwick’s film Glory (1989)

- Highlight/underline and annotate the most important points; be sure you review the questions before we view the film.

- Pay attention and answer the questions in the time allotted following the end of the film.

Background: The issues of emancipation and military service were intertwined from the onset of the Civil War. News from Fort Sumter set off a rush by free Black men to enlist in U.S. military units. They were turned away, however, because a federal law barred Negroes from bearing arms for the U.S. Army. The Lincoln administration was concerned that the recruitment of Black troops would prompt the Border States (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri) to secede. By mid-1862, however, the escalating number of former slaves (contrabands), the declining number of white volunteers, and the needs of the Union Army pushed the Government into reconsidering the ban. As a result, on July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, freeing slaves who had masters in the Confederate Army. Two days later, slavery was abolished in all the territories of the United States. In the Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, President Lincoln announced that Black men would be recruited into the U.S. Army and Navy. Abolitionist leaders such as Frederick Douglass encouraged Black men to become soldiers to ensure eventual full citizenship (two of Douglass’s own sons enlisted). By the end of the Civil War, roughly 188,000 Black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers and another 19,000 served in the Navy. 40,000 Black soldiers died over the course of the war. There were 80 Black commissioned officers; 21 Black soldiers and sailors won the Medal of Honor by the time it ended. Black women could not formally join the Army but served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous scout being Harriet Tubman. In addition to the perils of war faced by all Civil War soldiers, Black soldiers faced additional problems stemming from racial prejudice. Segregated units were formed with Black enlisted men commanded by white officers. Black soldiers were initially paid $10 per month from which $3 was automatically deducted for clothing, resulting in a net pay of $7. In contrast, white soldiers received $13 per month from which no clothing allowance was drawn. In June 1864, Congress granted equal pay to the U.S. Colored Troops.

The film: Glory tells the story of the 54th Colored Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the most celebrated regiments of Black soldiers that fought in the Civil War. Known simply as “the 54th,” this regiment became famous after the heroic, but ill-fated, assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina. Leading the direct assault under heavy fire, the 54th suffered enormous casualties before being forced to withdraw. The courage and sacrifice of the 54th helped to dispel doubt within the Union about the fighting ability of Black soldiers and earned this regiment undying battlefield glory. Of the 5,000 Federals who took part, 1,527 were casualties: 246 killed, 890 wounded and 391 captured. The 54th lost a stunning 42 percent of its men: 34 killed, 146 wounded and 92 missing and presumed captured. By comparison, the Confederates suffered a loss of just 222 men. Despite the 54th’s terrible casualties, the battle of Fort Wagner was a watershed for the regiment. Civil War scholar James McPherson states, that the “significance of the 54th’s attack on For Wagner was enormous. Its sacrifice became the war’s dominant positive symbol of Black courage. Their sacrifice sparked a huge recruitment drive of Black Americans. It also allowed Lincoln to make the case to whites that the North was in the war to help bring a “new birth of freedom” to all Americans.

Questions – Answer all questions in complete sentences on a separate sheet of paper:

- List 2 reasons why men joined the 54th?

- Why do you think the white officers volunteered to lead them?

- Why do you think Colonel Shaw wants his regiment to lead the deadly assault on Fort Wagner?

- In the scene just before the final attack, Shaw approaches a reporter and says, “Remember what you see here.” Write a brief newspaper entry including a headline, dateline, photo (or drawing, engraving, map, etc.) and caption, and a brief (3-4 sentences) description stating what the reporter saw at the Battle of Fort Wagner.

In-class group activity: We will divide randomly into 4 groups. Each group will be assigned one of the images below. Your group will determine how the image represents the significance of the 54th’s achievements and legacy. Each group will then report back to the rest of the class.

Further reading:

Russell Duncan. Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Robert Gould Shaw. This book contains a 67-page biography of Shaw as well as 300 additional pages featuring the various letters Shaw wrote to family members, some of which are read in the movie.

Joseph T. Glatthaar. Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. Paperback. Louisiana State University Press (April 2000).

David Blight’s article, “Race and Reunion: Soldiers and the Problem of the Civil War in American Memory” (6, no. 3 [2003]: 26-38).

A: Storming Fort Wagner. Lithograph by Kurz & Allison, 1890

Image B: Civil War photograph of Sergeant-Major Lewis H. Douglas, one of the first troops of the 54th to climb over the walls of Fort Wagner during the attack.

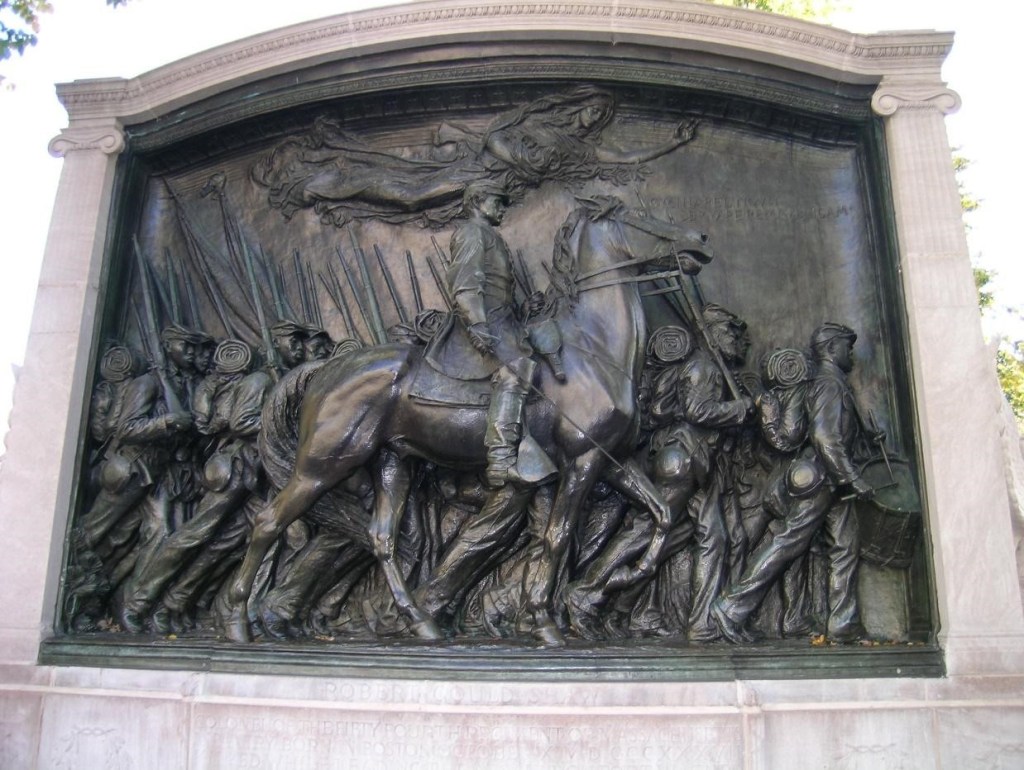

Image C: Augustus Saint-Gaudens (one of the premier artists of his day) took nearly fourteen years to complete this high-relief bronze monument, which celebrates the valor and sacrifices of the Massachusetts 54th. Colonel Shaw is shown on horseback and three rows of infantrymen march behind. This scene depicts the 54th Regiment marching down Beacon Street on May 28, 1863 as they left Boston to head south. The monument was unveiled in a ceremony on May 31, 1897.

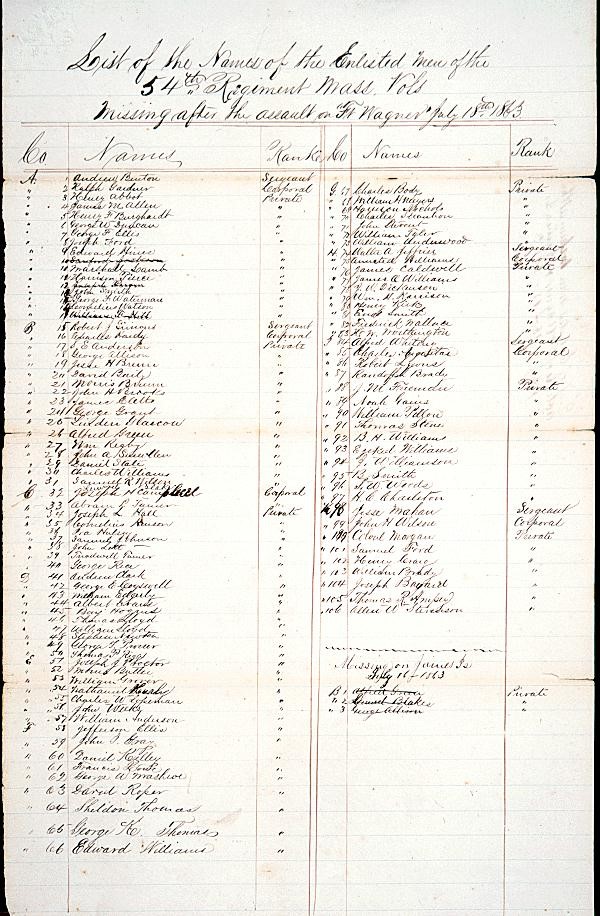

Image D: One of the 54ths casualty lists with the names of 116 enlisted men who died at the battle for Fort Wagner. National Archives, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917