New Jersey Council for the Social Studies

Engaging High School Students in Global Civic Education Lessons in U.S. History

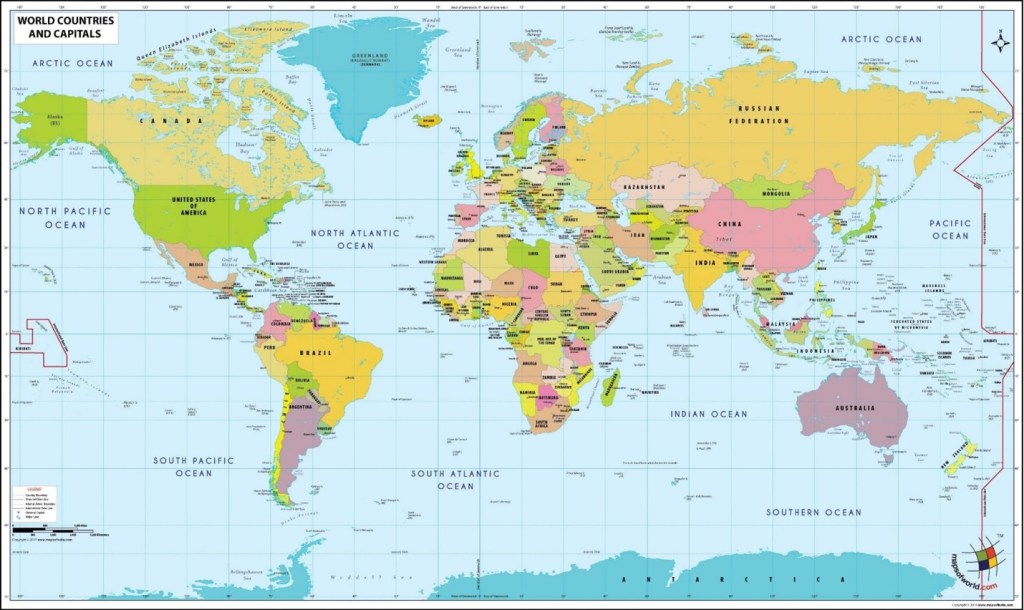

The relationship between the individual and the state is present in every country, society, and civilization. Relevant questions about individual liberty, civic engagement, government authority, equality and justice, and protection are important for every demographic group in the population. In your teaching of World History, consider the examples and questions provided below that should be familiar to students in the history of the United States with application to the experiences of others around the world.

These civic activities are designed to present civics in a global context as civic education happens in every country. The design is flexible regarding using one of the activities, allowing students to explore multiple activities in groups, and as a lesson for a substitute teacher. The lessons are free, although a donation to the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies is greatly appreciated. www.njcss.org

Era 13 Postwar United States: Civil Rights and Social Change (1945 to early 1970s)

The postwar era marked the rise of America as a world power. The new world order established alliance and economic agreements that have led to unprecedented economic growth. However, this period also marks divisions between countries with democratic institutions, authoritarian governments following the ideology of Marxist communism, and developing countries with issues of poverty, disease, debt, and human rights abuses. The United States faced issues or racial segregation, a shrinking middle class, and the expansion of costly federal government programs and a large defense budget causing its national debt to increase. Technology and the media influenced social changes.

Activity #1: Federalism: Dixiecrats in the United States and the Swiss Cantons

Dixiecrats and the Authority of State Government in the United States

The principle of federalism is valued in the way the people of the United States govern themselves. There is a fine line between the division of powers between the states and the national government. The Tenth Amendment specifically protects the powers of the 50 states, and the Ninth Amendment protects the powers of individual citizens. The powers of the national government are carefully defined and limited.

“The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” (Ninth Amendment)

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” (Tenth Amendment)

“The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States; he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices, and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” (Article 2, Section 2)

“He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient; he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper; he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers; he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, and shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.” (Article 2, Section 3)

The Dixiecrats perceived the legislation passed by the national government (Congress and President Truman) to integrate American society as a threat to their liberty and authority as independent states. In the 1948 presidential election, Southern Democrats walked out of the Democratic National Convention because they disagreed with its civil rights platform. They formed a new political party with South Carolina’s Governor Strom Thurmond as their party’s presidential nominee. Their objective was to deny or ‘nullify’ laws passed by the national government to integrate schools and modes of transportation. Individual states wanted to continue with the 1896 “separate but equal” decision from the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson.

In 1798, Congress passed, and President John Adams signed into law, the Alien and Sedition Acts. The acts outraged Thomas Jefferson and Kentucky declared the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional and “altogether void and of no force” in the state of Kentucky.

Kentucky held that our Constitution was a “compact” among the states that delegated a set of limited powers to the federal government. This meant that “every state” had the power to “nullify of their own authority” any violation of the Constitution. In 1832, South Carolina declared the Tariff of 1832 was unconstitutional, “null, void, and no law” because they disproportionately burdened southern states.

“This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” (Article 6)

Switzerland’s Government

Switzerland is governed under a federal system at three levels: the Confederation, the 26 cantons and the 2,131 communes. The Swiss Confederation of States and its current boundaries were agreed to in 1815 and its current constitution was adopted in 1848. Switzerland has a direct democracy with citizens voting on decisions at all political levels. Switzerland is governed by the Federal Council of seven members representing the different political parties and are elected by the two-house assembly or parliament. whose decisions are made by consensus. Switzerland has a two-house assembly, the National Council is the lower house and represents the people. The upper house is the Council of States and represents the individual cantons. Switzerland also has ten political parties. The powers of cantons include education, culture, healthcare, welfare, law enforcement, taxation, and voting. Cantons have their own constitutions, parliaments, and courts, which are aligned with the federal constitution.

An example of a conflict in Switzerland that challenged the authority of the individual cantons is the city of Moutier with a population of 7,500 in the canton of Bern. Since 1957, the Moutier committee wanted to secede from the canton of Bern and join the canton of Jura. The majority of people in Bern have voted to keep Moutier within its jurisdiction. Four out of the seven Jura districts narrowly rejected forming a new district. The three northern, majority Roman Catholic, districts voted in favor of a new district.

Since 2013, there have been peaceful protests and at times vandalism. The people of Moutier voted to join the Jura canton making it the second largest town in the canton of Jura. Although a majority, 51%, of the people voted to join, the government and people of Bern declared their vote to be invalid because some people voted whose residency could not be confirmed. There have been nine referendums in the past 70 years with the population voting to secede and join the Canton of Jura in 2021. The change to the canton of Jura took effect on January 1, 2026, granting Moutier the right to secede from one canton and join another.

Questions:

- Should the national government of the United States be able to enforce common laws for holidays, the economy, schools, transportation, public health, and the environment in all 50 states and territories?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of the federal system of power between the individual states and the national government in the United States?

- Does the Swiss government model have any advantages or disadvantages over the structure of government in the United States?

- What would be the best way to resolve the conflict with the population of Moutier?

- Will the decision allowing Moutier to secede establish a precedent for future towns or cities to secede in Switzerland?

Platform of the States Rights Democratic Party, August 14, 1948

Article 1, Section 8: Federalism and the Overall Scope of Federal Power

Keeping the Balance: What a President Can and Cannot Do (Truman Library)

Looking Back: Nullification in American History (National Constitution Center)

Political System of Switzerland

Activity #2: Elementary and Secondary Education Act and Canadian Aid to Schools

Education is primarily a state and local responsibility in the United States. About 92% of the money for elementary and secondary education comes from local taxes and money from the individual states. The role of the federal government in education dates back to 1867 when Congress wanted information on teachers and how students learn. Over time this led to land-grant colleges and vocational schools After World War 2, the federal government enacted the “GI Bill” to provide college and vocational education to returning veterans.

In response to the Soviet launch of a satellite, Sputnik, into space in 1957, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act to provide funds for teachers in the areas of mathematics, science, world languages, and area studies to enable us to compete with the Soviet Union. Perhaps the most significant legislation to increase federal funds for schools came in response to the passage of civil rights laws in the 1960s and 1970s and the Great Society programs to reduce poverty. In 1980, Congress established the Department of Education as a position in the president’s Cabinet. In 2025, the Department of Education’s staff and budget was significantly reduced. The Department of Education before 2025 supported 50 million students in 98,000 public schools and 32,000 private schools. They also provided grants, loans, and work-study programs to 12 million students in colleges and vocational training programs. In addition, they administered $150 billion in loans.

The purpose of federal funds in the United States is to provide equality for disadvantaged students and to improve academic achievement. This is monitored through state assessments based on learning standards. Unfortunately, some states lowered their expectations for student achievement to qualify for the federal funds and the federal government is currently investigating fraud in how federal dollars are being spent.

In the United States, federal funds are designated for after school instruction, English language acquisition, preschools, nutrition, literacy, teaching American history and civics, charter, and magnet schools.

School Financing in Canada

School funding in Canada is primarily a responsibility of provincial and territorial governments. The federal government contributes money to ensure an equal education for its significant indigenous population. Most funding is from Canada’s 10 provinces. Some provinces provide public funding to private, charter, and religious schools.

The government of Canada views education as a public good from which everyone in society benefits. Education prepares students for jobs, higher education, lowers crime, and reduces poverty. Employers also benefit as educated workers are more productive leading to higher profits for businesses. The only province to fully embrace school choice is Alberta. Canadians fear that school choice may lead wealthier Canadians to benefit from independent, parochial, charter, or magnet schools and this would leave marginalized populations at a disadvantage. Equality and equity are two principles that Canadians value.

According to U.S. News & World Report, the United States is ranked #1 and Canada is ranked #4 in the world in education.

Questions:

- Should local communities, states or provinces, or the national government decide the curriculum and funding for public schools?

- To what extent should public tax dollars be used to support private or religious schools?

- What is the best way to ensure an equal and equitable education for all students?

- Should public tax dollars be used for extracurricular activities and sports in schools?

- Do you consider education to be a public good that benefits all of society or is it a private good that benefits individual students?

- To what extent should public tax dollars be used to support college and vocational education after completing elementary and secondary education?

Elementary and Secondary Education Act

Canada’s Approach to School Funding

Council of Ministers of Education, Canada

Activity #3: Segregation by Race in the United States and by Religion in India

De facto Racial Residential Segregation in the United States

The United States ended racial segregation with the Brown v. Board of Education v. Topeka, Kansas decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, the United States continues to be a place of segregation, not integration. Residential segregation exists through our zip codes and neighborhoods. Although our laws prohibit discrimination, differences in land use policies, wealth and income, contribute to what is called de facto racial residential segregation. Neighborhoods determine the quality of schools, public safety, quality of drinking water, opportunities for employment, strategies of law enforcement, rates of incarceration, and life expectancy.

A study by the University of California (Source) found that more than 80 percent of metropolitan areas were more segregated in 2019 than in 1990. In 2025, the United States government effectively ended support for DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) programs. Racial residential segregation is difficult to address when resources are not equally available to all communities. The Kerner Commission wrote in its 1968 report that integration is “the only course which explicitly seeks to achieve a single nation” rather than a dual or permanently divided society.

Table 3: Top 10 Most Segregated Metropolitan Statistical Areas (2019, Minimum 200,000 people)

| Segregation Rank | Metro |

| 1 | New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA |

| 2 | Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI |

| 3 | Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI |

| 4 | Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI |

| 5 | Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL |

| 6 | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA |

| 7 | Trenton-Ewing, NJ |

| 8 | Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH |

| 9 | Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

| 10 (tied) | Beaumont-Port Arthur, TX |

| 10 (tied) | New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA |

Religious Segregation in India

India ended the caste system in 1947 and yet many Indians live in religiously segregated areas. One of the reasons for this segregation is that friendship circles are often part of the religious community and marriages are within the same faith community. People in southern India are most likely to live in integrated neighborhoods. Indians with a college degree are more accepting of people from other faiths living in their neighborhoods than those with less education.

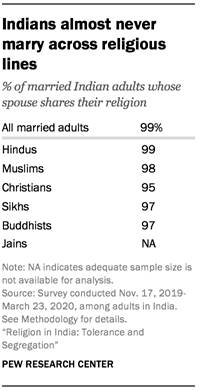

Very few Indians say they are married to someone with a different religion. Almost all married people (99%) reported that their spouse shared their religion. This applies to Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs and Buddhists.

Indians generally marry within same religion

Religion, especially members of the Hindu faith, is closely connected with views on politics and national identity. Hindus make up 80% of India’s population. A Pew Research study found that 36% of Hindus would not be willing to live near a Muslim, and 31% say they would not want a Christian living in their neighborhood. Jains are even more likely to express such views:. 54% of people who identify with the Jainist faith would not accept a Muslim as a neighbor, and 47% say the same about Christians. People who identify as Buddhist tend to be the most accepting of people from other faith traditions. Eight-in-ten Buddhists in India say they would accept a Muslim, Hindu, Christian, Sikh or Jain as a neighbor.

Members of both large and small religious groups mostly keep friendships within religious lines

And Indians who live in the Central region of the country are more inclined than people in other regions to say it is very important to stop people from marrying outside of their religion. Among Hindus in the Central region, for instance, 82% say stopping the interreligious marriage of Hindu women is very important, compared with 67% of Hindus nationally. Among Muslims in the region, nearly all (96%) see it as crucial to stop Muslim women from marrying outside the faith, versus 80% of Muslims nationally.

The religious segregation also impacts the quality of education and employment. Muslim student enrollment is dropping. Some states in India are banning religious instruction even though it is protected by the national constitution.

Questions:

- Are there common factors (geographic, social, economic, racial, educational, religious, etc.) causing different kinds of segregation in Indian and the United States?

- How can countries best establish a social system of equality and integration?

- Is segregation present in your school or community?

- How do countries/societies unite or define their identity?

- Is the problem of segregation about the same, more severe, less severe in India or the United States?

Examples of Government Regulation of Business in the United States

Religious Segregation in India (Pew Research Center)

Activity #4: The Great Society Programs and The Marshall Plan for Europe

The Great Society Program in the United States

In 1965, according to the U.S. Census, the poverty rate in the United States was 13.3%. In 2024, it was 10.6%. However, poverty rates often provide mixed data because of inflation, income levels, race, and age. For examples in 1965 45% of the population in South Carolina was below the poverty line and in 2024 the poverty rate for Hispanic (15%), Black Americans (18.4%), and Native Americans (19.3%) is significantly higher than 10.6%. The definition is further complicated by the difference between absolute poverty (below an income of $31,200 for a four-person household) and relative poverty (the quality of life for people in a neighborhood or community).

Social Security and Medicare are for senior citizens who are eligible at age 65 for Medicare and age 67 for Social Security. There are 83 million people, including children, receiving Medicaid, about 25% of the population. The program is offered by the states and the services provided depend on the state. An average estimate for eligibility is an income that is about 140 percent above the federal poverty level ($30,000 for a family of two in New Jersey, as of 2026). In New Jersey, Medicaid costs about 23% of the state’s budget. Approximately 25% of the residents in New Jesey receive Medicaid at an average cost of $2,600 per enrollee. Amounts vary and are higher for families with children and pregnant women.

According to the Congressional Research Services, mandatory spending was only 30% of the federal budget. Today, it is 60%. Medicare and Medicaid together cost nearly $1 trillion annually. Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, are the main contributors to our national debt, which is now over $40 trillion (or roughly $59,000 per citizen). According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicare provides health insurance coverage to 68 million Americans. Funding for Medicare is from government contributions, payroll tax revenues, and premiums paid by beneficiaries. Medicare spending is currently about 13.5% of the federal budget or roughly $1.1 trillion. The average cost is $17,000 per enrollee with a $12 billion shortfall in 2023, about $1,300 per enrollee. The administration of President Trump cut some of the Medicaid programs in 2025 and is negotiating lower prescription drug costs to reduce this shortfall. An aging population and higher health care costs are factors that are expected to continue. Even with these Great Society programs, poverty among the elderly is significantly high. According to USA Today,

“Based on the official measure, which is a simple calculation based on pretax cash income compared with a national threshold, the percentage of seniors in poverty rose to 9.9% last year from 9.7% in 2023, data showed. Using the more comprehensive supplemental measure, which includes noncash government benefits, accounts for taxes and essential expenses like medical care and work-related costs, and adjusts thresholds for regional differences in housing costs, senior poverty rose to 15% from 14.2% − and marked the highest poverty level among all age groups.”

Although these programs are not cost effective and are withdrawing funds from the Trust Fund, they are considered transfer payments because the money is spent at the local and state level which generates income and GDP growth in the economy. They are often referred to as entitlement programs because they were passed by Congress and have been in effect for 90 years (Social Security) and 60 years (Medicaid and Medicare) and revised and expanded over time.

Marshall Plan

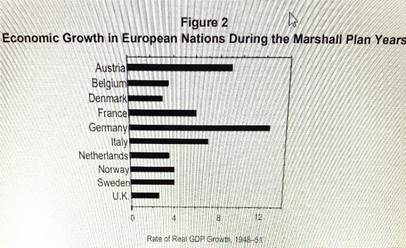

In June 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall, announced the U.S. plan to give economic aid to Europe. The offer was made to all of Europe, including the U.S. wartime enemies and the communist countries of Eastern Europe. Sixteen European countries responded by cooperating on a plan that was accepted by the United States. The United States appropriated $13.6 billion (equivalent to $190 billion in 2026 money) was provided. By 1950, the economies of the participating countries returned to their prewar levels.

The Marshall Plan required the countries to stabilize their currency, reduce public spending, import goods from the United States and increase their exports to the United States. There were clear expectations that benefited the economy of the United States. The Marshall Plan established the U.S. as a dominant economic power, promoted open trade and prevented the return of economic depression. It was critical in forming NATO and a closer relationship between the United States and Europe.

Questions:

- Given the fact that the Great Society programs of Medicaid and Medicare are not cost effective and that the poverty rate for people over the age of 65 has increased, should the United States continue with these programs?

- What should the United States or the individual states do to lower the poverty rate among people over the age of 65?

- Does the United States have a legal (constitutional) or moral responsibility to provide supplemental or full health care for its citizens, legal residents, and/or undocumented immigrants?

- Was the Marshall Plan worth the investment by the United States?

- What factors contributed to the success of the Marshall Plan?

- Would a ‘Marshall Plan” to support the rebuilding of a sustainable infrastructure based on renewable energy be effective and accomplish similar outcomes within three to five years?

Tallying the Costs and Benefits of LBJ’s Great Society Programs (American Enterprise Institute)

Estimates of the Costs of Federal Credit Programs (Congressional Budget Office)

Kaiser Family Foundation Reports on Medicare-Medicaid Enrollment and Spending

Marshall Plan (1948) (National Archives)

Marshall Plan and U.S. Economic Dominance (EBSCO)

The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Significance (Congressional Research Service)