An Interview on Teaching about Controversial Subjects in Today’s Political Climate

by Sepideh Yasrebi and Alan Singer

Sepideh Yasrebi: Given your extensive work on curriculum design in social studies education both as a former teacher and an academic, how do you understand the role of narrative—both dominant and counter-narratives—in representing or resisting ideology in the classroom?

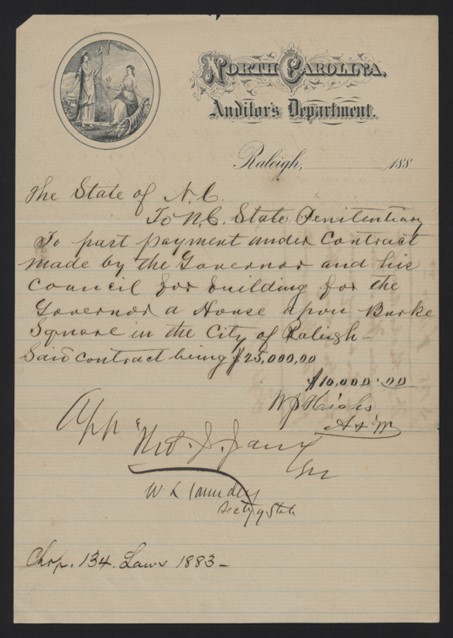

Alan Singer: I think your point is that history is very much a story about the past. The difference between history as practiced by historians and cultural indoctrination as championed in Donald Trump’s vision of teaching patriotic history is that historians start with questions about the past and present and examine the past seeking answers to their questions in an effort to understand the present. Historians always have a point of view, but in a scientific approach to understanding the past, you always must be prepared to rethink your views based on data and analysis.

What this means in the social studies classroom is that we don’t want students to just accept what the textbook or curriculum says, but we want them to raise their own questions with the material they are being presented with. We also want to provide them with material from different perspectives so that they learn to weigh the validity of different explanations. Our goal is for them to think like historians to prepare them to be active citizens in a democratic society. At the end of the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin was asked what type of government the delegates had created. Franklin’s reply reverberates today. Franklin said, “A republic, if you can keep it.” We need to equip students so the United States will remain a democracy, if they can keep it.

Sepideh Yasrebi: Fredric Jameson’s concept of cognitive mapping invites individuals to represent, however incompletely, their relationship to the broader social and ideological totality. How might this idea be translated into meaningful classroom practice? In other words, how can social studies curriculum and pedagogy help students connect their lived experiences to larger historical and structural forces in ways that foster critical historical thinking and agency?

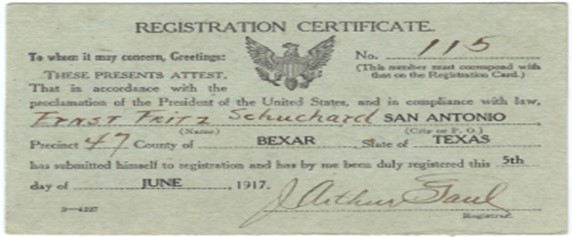

Alan Singer: I used to promise high school students that at one point during the school year, they, their families, and the groups they identified with would be part of the curriculum – and the students held me to it. Sometimes it was difficult to include some of the most recent immigrant groups, but when we came to changes in immigration to the United States in 1965, I invited students from newer immigrant groups to be part of a panel where they explained their families experience leaving their homeland and coming to the United States. The class would then compare the push and pull factors of the newer immigrant groups with groups we had studied in early waves of immigration. Working with teacher in the Hofstra program, we adapted this idea for elementary and middle school students. In those grades we created family artifact museums. Each student brought a material object to class that was important to their family culture. They created a museum card describing the artifact, and students traveled around the room learning about each other’s cultures.

Sepideh Yasrebi: Are national and state social studies standards helpful or a hindrance in achieving social studies learning goals?

There are no national social studies standards in the United States so each state Department of Education develops their own. I am most familiar with New York State and New Jersey social studies standards which both strongly support document-based instruction, promoting critical thinking, and preparing students for full participation as citizens. National organizations like the National Council for the Social Studies, the American Historical Association, and the Organization of American Historians also promote these goals. Unfortunately, even though they are in the standards does not mean that we see them in practice in classrooms. Too much of teaching centers on preparing students for state and national reading skill exams that are used to evaluate school districts, schools, and teachers.

Sepideh Yasrebi: What tensions do you observe between traditional “fact-based” approaches to history education and more interpretive, narrative-driven models—especially in today’s sociopolitical climate? How do you navigate these tensions in teacher preparation program?

Alan Singer: I think the two keys are building respectful classroom communities where students can have open dialogues and creation of document packages with different perspectives on difficult issues for students and teachers to evaluate. I generally will only offer my opinion as part of a community discussion if I believe it opens up the discussion. Generally, I will include documents that express views similar to my own in the package so I never have to express my ideas, they are already there for students to evaluate.

Sepideh Yasrebi: How do you teach preservice teachers to allow their students to be critical thinkers in a society that does not seem to value critical thinking?

Alan Singer: I recognize that the function of schooling in any society is to perpetuate that society by inculcating the hegemonic values of that society. In the United States schools are expected to reinforce dominant beliefs including that the system is fair, people achieve success based on merit, and that anyone can achieve through hard work. Part of this belief system is that if an individual fails it is their own fault or because of their own inadequacy. Too often I have heard teachers say “I didn’t fail you. You failed you. I only entered the grade.” A critical approach to history and social studies includes questioning these beliefs. Martin Luther King Jr. called on people challenging the dominant ideas of society to employ “creative maladjustment,” identify with the expressed values of society, but interpret them in your own way. Herbert Kohl applied the idea of creative maladjustment to the classroom. He recommended that teachers use the language of the standards but interpret them in ways that allow you to connect with your students and engage them in necessary conversations about the past and present.

Sepideh Yasrebi: In this study, I define narrative competence not just as the ability to tell stories, but as the capacity to critically situate those stories within broader historical and ideological contexts. From your perspective, how can curriculum and pedagogy foster this kind of competence in students? Are there particular texts, historical narratives, or teaching practices you’ve found especially effective in supporting this work—or that you help teacher candidates implement in their own classrooms?

Alan Singer: I see reading as a conversation with an author or document. I tell students that they are not just reading to learn information and answer the questions that I ask, but to formulate their own questions, ask the author, see if the answer is in the text, and if they are not satisfied with an answer, develop a strategy to discover what they want to know. Similarly, writing is a form of edited thinking. Write down your ideas. Don’t be afraid of spelling, grammar, or uncertainty. But after you write them down, edit them so they make sense to you. Then edit them again into formal language that will make your ideas accessible to other people. This makes it possible to extend our conversation to a broader audience. To facilitate this approach, I organize teams of writing buddies who read each other’s work, suggest corrections, but also point out points that need greater explanation.

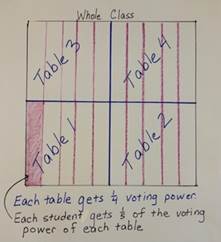

Again, the practices you want to see in classrooms will only happen when there is respectful dialogue. Our goal is to learn together, to share ideas, not to win or to silence others. That type of community can take a while to build, but it is essential if students are to become critical historians and responsible citizens in a democratic society. I never lecture. When I talk to much it means I failed to design an effective lesson plan. My role in the classroom is to introduce material and question students as they evaluate primary and secondary source material. What does the text say? What does the text mean? What are your views of the text? What is the evidence presented to support the author’s view? What is the evidence to support your views?

Sepideh Yasrebi: What does a culturally sustaining approach to social studies education look like to you, particularly in relation to multilingual and racialized students whose identities have often been marginalized in U.S. schools? Do you believe CSP has been meaningfully incorporated into social studies teacher education? What are the shortcomings?

Alan Singer: I discussed this earlier with suggestions for student panels and a family artifact museum. I want to share an anecdote that helped me better understand a culturally sustaining approach to teaching. I grew up in the 1950s in the shadow of the European Holocaust. We were a Jewish family that never discussed the Nazi extermination of Jews. It wasn’t until I was in college that I learned from my grandfather that his father and most of their village were murdered by German troops including my grandfather’s brother’s wife and her two children. Growing up in the shadow of the Holocaust there was family silence and embarrassment at our victimization when we learned about it in high school. It wasn’t until Israel emerged as a significant force in world affairs in the 1960s that my peers and I stopped seeing Jews as just victims. When I was a high school social studies teacher, I always included an extended unit on slavery in the United States. One year an African American young woman challenged me in class and wanted to know why the only time Black people were included in the curriculum was to show how they were slaves. I asked her to talk to me after class to discuss how we could approach this differently. She and some of her friends met with me and I realized their reaction to learning about enslavement was very similar to mine learning about the Holocaust in high school. We decided together that I needed to change the focus of the unit from oppression to include resistance, especially by Black abolitionists.

This was my journey, but in answer to your question, it is not forcefully incorporated into state and national curricula and it is not the experience and understanding that many other teachers bring to the classroom. One group that promotes this approach to teaching is Rethinking Schools which also sponsors the Zinn Education Project.

Sepideh Yasrebi: How do you mentor future teachers to critically reflect on their own ideological positionings? How can teacher education programs support this view?

Alan Singer: Many of the prospective teachers in my teacher education program are very nervous about addressing controversial topics like racism, responses to immigration, or actions by the Trump administration that are constitutionally questionable in the classroom. No one wants to be targeted by Fox News or risk losing their job because of parental complaints. I stress that they have to know their stuff and be prepared to explain why they introduced the topics, questions, and documents they use in their lessons. The first step when they plan a lesson is to ask themselves, what is important to know and why? I also recommend that if they are unsure about a lesson, they should discuss their ideas with their department chair so if there are complaints, the department chair can explain the lesson approach, how it included multiple perspectives on the topic, and addressed state learning standards. I prepared a lesson on the Supreme Court’s 6-3 ruling barring federal district court universal injunctions that opened the way for the Trump administration to ignore the 14th amendment’s granting of citizenship to all people born in the United States. In the lesson, students are provided with excerpts from the majority opinion of the Supreme Court written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett and dissenting opinions by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson. I strongly agree with Sotomayor and Jackson that the Court’s decision, by granting the Trump administration the unchecked power to pursue highly questionable goals, is a threat to the rule of law in the United States, but I don’t plan to add my views to the discussion. The lesson is designed to show prospective teachers how to organize a conversation on a controversial topic like this and how to include multiple perspectives in their document packages.