American Exceptionalism’s Downward Trek: Declining Victory Culture in the 1990s Observed Through the Star Trek Franchise

By Brigid Rizziello

On January 3, 1993, the first episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine began with the Federation defeat at the Battle of Wolf 359. Captain Jean Luc Picard of the USS Enterprise had been captured and assimilated into the Borg Collective as Locutus of Borg and was forced to lead the battle against the Federation.[1] A fleet of Federation ships, including the USS Saratoga, attempted to engage Locutus in battle, but were quickly overpowered. First officer Benjamin Sisko assumed command of the Saratoga after the captain and majority of the bridge crew were killed and the ship was disabled. Sisko issued the order to abandon ship and went to help his wife and child. He located them in the remains of their living quarters buried under rubble; he was able to rescue his son, but his wife was already dead. Another officer forced him to leave her body behind and board an escape shuttle. As the scene fades, Sisko holds his unconscious son as he watches the Saratoga explode with his wife’s body still on board.[2]

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) presented a vastly different conceptualization of the future than the one Gene Roddenberry originally created in the 1960s series Star Trek: The Original Series (1966-1969).[3]Roddenberry intended to portray a hopeful future where mankind was able to move past conflict and explore the galaxy.[4] However, as the political atmosphere of the United States changed over time, the themes of the various series in the Star Trek franchise changed as well, especially after Roddenberry’s death in 1991. As a result of political and social turmoil in the 1990s, there was a disillusionment with the United States as an institution that culminated in a concurrent decrease in American exceptionalism and victory culture reflected through contemporary popular media. The concept of American exceptionalism refers to the celebratory ideology that Americans perceive the United States as inherently extraordinary. This is the result of its democratic nature and the unique “American identity” that can be claimed across race, class, and gender; factors that subsequentially makes it fundamentally superior to other nations.[5] One way that this dogma is reflected in American society is through the presence of victory culture, which reflects a glorified exceptionalist view of the nation in order to highlight American superiority and disseminate patriotic values to the populace. The development of an increasingly cynical view of America can be observed by charting and comparing Star Trek: Deep Space Nine with Star Trek: The Original Series in regard to the themes and plotlines of each series and how these changes reflect evolving responses to sociopolitical conflict and violence in the United States in the 1960s and 1990s respectively.[6]

The increased polarization in the United States in the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries is a highly contentious and relevant topic for the current political climate in America. Kevin M. Kruz and Julian E. Zelizer traced the increasing divide of American society between 1974 and 2019 in their book Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974.[7]They determined that economic, racial, political, and gender and sexual divisions are factors of the American experience which have exacerbated the “fault lines” of the United States by tracing their influence on major events between 1974 and 2019. The influence of these factors on American society increased significantly after the 1960s and 1970s because of the institutionalization of polarized ideologies through targeted legislation and widespread access to popular media. This structural division was particularly exacerbated by the end of the Cold War through the development of more accessible and increasingly partisan media news networks such as MSNBC, Fox News, and CNN, which compounded the preexisting divides among the American populace.

Another significant historical factor to consider when analyzing popular opinion through a television show is the influence of current events on the political climate, and how views of those events are reflected through media. Tom Engelhardt detailed the rise and fall of victory culture and American exceptionalism in the United States in his book The End of Victory Culture: Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation.[8]He claimed that victory culture, Engelhardt’s term for the propensity of American media and culture to highlight the nation’s military triumphs, gradually ended between the years 1945 and 1975. This was due to the memory of the United States’s actions during the Second World War, specifically the deployment of two atomic bombs onto a surrendering Japan, and the end of the unpopular Vietnam War. As a result, the United States decreasingly viewed conflict as a motivating force and congruently perceived war in a negative light. This was further exacerbated by the end of the Cold War through the loss of a unifying common enemy for the United States that Engelhardt, similarly to Kruze and Zelizer, claimed was critical for the collective victory culture-based American identity.

Analysis of the impact of the Cold War on American society is extensive, and many historians have documented its effect on different forms of film-based media, such as television and movies. Historians like Thomas Doherty, Jim Cullen, and Bryn Upton examined the impact of the Cold War on American film and television, independently demonstrating how contemporary events influenced cinematic themes. In his book Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture Doherty highlighted the influence of television on American society as a result of its increased presence in the majority of American households in the 1950s.[9] Additionally, he refuted common misconceptions regarding the connection between McCarthyism and Cold War era television, ultimately demonstrating that television resulted in social resistance which helped to make the United States a more inclusive place, in addition to aiding in the end of McCarthy’s policies, through the portrayal of an inclusive society.[10] Cullen wrote From Memory to History: Television Versions of the Twentieth Century where he examined how historical shows from the past half a century portrayed earlier decades as a way to understand the time they were created.[11] He determined that the majority of television shows function as interpretations of events, and episodes can be used as “artifacts” that are representative of when they were written to understand the past. Additionally, Upton wrote Hollywood at the End of the Cold War: Signs of Cinematic Change, where he compared pre and post-Cold War films with analogous themes, intending to understand how their “interpretive framework” was influenced by the culture of the period.[12] Similarly to Engelhardt, Upton determined that in the 1980s there was a negative shift in the United States’ perception of themselves after the end of the Vietnam War, which was further exacerbated by the loss of a common enemy with the end of the Cold War. This meant that the United States struggled to develop a new interpretive framework without the presence of the Cold War and a common external enemy such as the Soviet Union. He asserted that the end of the Cold War resulted in altered perception of concepts like heroism and villainy, where binary characters with simple motivations that reflect, or contrast, American values, evolved to become more complex with more detailed backstories and intentions.[13]

While there has been much written about the influences of current events on film before and after the end of the Cold War, there is a gap in general 1990s historical scholarship. The goal of this paper is to examine evolving public perception of the United States as an institution through comparative analysis of diminishing victory culture in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine in relation to Star Trek: The Original Series, in order to determine how American exceptionalism decreased in response to changing political landscapes and major historical events of the decade. While Englehardt argues that victory culture is depicted through media portraying American military triumph, this paper will demonstrate that victory culture is the medium used to disseminate American exceptionalist messages through cinematic plot regarding all perceived accomplishments of the United States in addition to militaristic triumphs. Furthermore, it will evaluate why the hopeful view of the future in the 1960s became significantly less optimistic in the 1990s, explore how public opinion was reflected in the Star Trek franchise, and analyze the role that televised media played in social commentary during the second half of the 20th century. In its conclusion, this paper will also provide pedagogical suggestions for social studies educators on ways they can incorporate science fiction media into the classroom using the analysis in this paper, given the educational practice of utilizing film to engage students as a result of their accessibility and engaging nature.[14]

The 1960s were characterized by perpetual social upheaval and political conflict that stemmed from the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the Cold War in the 1940s. This was paralleled by the resulting foreign and domestic tensions of the Cold War as the United States government waged an ideological conflict against communism through the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s, in addition to a war of mutual destruction with the Soviet Union until its collapse in 1991. During the Reagan Administration in the 1980s, conflict between Republicans and Democrats increased exponentially in response to the revitalization of the conservative base and a heightened focus on moral politics that subsequentially amplified patriotism throughout the United States.[15] This increased focus on morality culminated in the 1990s culture wars, where the Clinton Administration and the conservative base clashed over moral and values based politics.[16] Additionally, the expanding involvement of the United States military in the affairs of foreign nations and increasing instances of foreign and domestic terrorism at the end of the 20th century exacerbated tensions that were reflected in popular media of the time. As a result, social discord and political fearmongering characterized by heightened sociopolitical conflict and violence was amplified in the 1990s relative to the 1960s.

Ideological and Sociopolitical Transformations

Since the founding of the United States, there has been an ongoing conflict over the amount of power that the federal government should be able to exert over the individual states and citizens. This conflict was exacerbated in the twentieth century following the implementation of the New Deal, resulting in an ongoing ideological dispute over the responsibility of the United States government to provide welfare assistance to its citizens through a federal social safety net after the pervasive homelessness and poverty experienced during the Great Depression.[17] An additional societal challenge of the late twentieth century was combating high crime rates seen in inner cities that arose in combination with substantial poverty, resulting in a mass incarceration crisis caused by 1960s legislation which disproportionally targeted people of color.[18] This was accomplished through the criminalization of urban spaces through legislation designed to incarcerate minority populations through drug-based crimes that resulted in the relocation of African Americans from urban cities to rural prisons, culminating in a conservative shift during the post-war period. Another social concern of this time was the Johnson Administration’s War on Poverty in response to the pervasive poverty rates in the United States. Moreover the 1980s Reagan era caricature of the “welfare” queen created a negative stereotype that targeted and incarcerated primarily African American women who were suspected of committing welfare fraud, further increasing mass incarceration rates.[19] Furthermore, expedited deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals in the 1990s resulted in the imprisonment of a disproportionate number of people with mental illness who could not access proper psychiatric care in the United States.[20] In response to the culture wars of the 1990s, the Clinton Administration expanded on legislation that limited access to government welfare programs in addition to laws that increased mass incarceration for drug crimes that compounded pre-existing mandatory minimum sentence requirements.[21]

Themes of mass incarceration and poverty are reflected in episodes of both Star Trek: The Original Series and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, which can be used to the determine the zeitgeist of each era in relation to American exceptionalist themes by examining the presence of victory culture in each series. The Original Series provided a significantly more glorified interpretation of social progress than Deep Space Nine, which demonstrates the contrasting overwhelming absence of American exceptionalism in the 1990s. For instance, the 1967 episode of The Original Series “The City on the Edge of Forever” and the two-part 1995 Deep Space Nine episode “Past Tense” both have time travel-based plots where main characters travel back in time to preserve their future. Both episodes center around the significance of advocacy and combatting poverty but have vastly different perspectives regarding the methods that the government should implement to help impoverished citizens. The main characters of each series function as the perspective of the contemporary viewer and can be used to assess the perception of the general populace on sociopolitical developments by examining how they respond to their experiences in the past. Furthermore, the events in these episodes can be used to gauge the general perspective of the public towards the United States as an institution during each decade in response to specific current events by assessing the presence of celebratory victory culture themes in each series.

In “The City on the Edge of Forever,” Captain James Kirk and First Officer Commander Spock travel back in time to New York in 1930 to restore the “correct” timeline after it was disrupted.[22] When they arrived in New York City they encountered Edith Keeler, a social worker from a local soup kitchen at the 21st Street Mission, who, in exchange for working at the soup kitchen, assisted them with getting jobs and an apartment. Keeler was presented as a progressive thinker through her enlightened view of humanity’s future. However, this was contrasted by her belief that only the “deserving poor” who were not at fault for their circumstances and continued to work despite their misfortune, should receive assistance. This dichotomy is demonstrated through the daily speech she gave to the mission’s attendants before meals as “payment,” where she said:

I’m not a do-gooder. If you’re a bum, if you can’t break off with the booze, or whatever it is that makes you a bad risk, then get out…One day soon, man is going to be able to harness incredible energies…that could ultimately hurl us to other worlds in…some sort of spaceship. And the men that reach out into space will be able to find ways to feed the hungry millions of the world and to cure their diseases. They will be able to find a way to give each man hope and a common future.[23]

The contradiction of this speech emphasizes themes of Social Darwinism and rugged individualism, the belief that people are responsible for their own economic success or failure. By beginning the speech with a demand for “bad risks” to leave based on their reliance on alcohol she distinguished those who were undeserving of help by highlighting the traits she found to be disagreeable. Her contrasting belief in a brighter future was demonstrated in the speech when she discussed how technological advancements and travel to different planets would ultimately resolve the social problems faced during the Great Depression.

During the early years of the Great Depression, before the New Deal revolutionized government-based welfare and federal economic intervention programs in the United States, it was believed that charities should hold the majority of the responsibility for helping the less fortunate. Social workers, like Keeler, were known to have a more progressive view regarding the causes of issues like poverty based on their mission to use grassroot methods to counteract societal inequity by working directly with poor communities through advocacy and education. [24] However, at the time many social workers were also heavily involved in the prohibition movement due to their belief that alcoholism was a disease caused by poor life choices and subsequentially felt that the 18th Amendment outlawing the sale of alcohol in the United States significantly improved the morals and conditions of low income communities.[25] As a result, Keeler’s contradictory assertions that she would not provide assistance to those who were undeserving of help, especially alcoholics, while preaching about the bright future of humanity would be socially acceptable within the context of the period and her chosen profession.

In response to the high rate of poverty in the United States, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a national war on poverty in his 1964 State of the Union Address. In 1966, Vice President Hubert Humphrey wrote an article detailing the goals of the War on Poverty and the Johnson Administration’s actions to eliminate poverty in the United States. [26] Humphrey identified that the independent actions of private charity and the federal government counteracted each other and claimed that they could not simultaneously exist if they continued to operate autonomously.[27] He also acknowledged that before the implementation of the War on Poverty, the dominant American philosophy regarding welfare reflected Social Darwinist perspectives, and recognized that there were many people who still held these beliefs. The federal welfare legislation that Humphrey supported was extremely progressive for the time and did not align with the beliefs of many Americans in the increasingly polarized political climate of the 1960s due to the connection of welfare to racial politics and the fact that it was perceived as an example of federal overreach.[28]

The lack of reactions by Kirk and Spock, in public and in private, regarding Keeler’s statements and the poverty crisis in New York City because of the Great Depression, indicated that they were, at the very least, ambivalent toward her actions. For instance, they could be observed discussing the barbarity of the period but do not provide any commentary on their observations or show any desire to help the people that they encountered in the past. Through Kirk and Spock’s inaction and Keeler’s unwillingness to help individuals that she saw as undeserving, “The City on the Edge of Forever” comments on the philosophies that Humphrey counteracted in the War on Poverty article which reflected common perspectives on poverty, homelessness, and the undeserving poor in the 1960s. Furthermore, the ongoing debate regarding the responsibility of private charities to help citizens verses government funded federal assistance can be observed in the episode based on Keeler’s role as a social worker who ran a private charity organization in New York and subsequent status as the sole social services provider in the episode.[29]

The inflated importance of the United States in The City on the Edge of Forever is representative of the American exceptionalist views of the 1960s and provides an example of victory culture regarding the social progress of the United States through the revelation that deviating from the status quo would result in an undesirable future. In the episode, Spock discovered that Keeler needed to die in a traffic accident because in the version of events where she lived, Keeler developed a peace movement which delayed the United States’ entry into World War II thus allowing the Nazis enough time to develop the atomic bomb and win the Second World War. As a result, humanity stagnated and was incapable of developing sufficient technology to reach space, thus preventing the conception of the United Federation of Planets; the governing interplanetary union in the Star Trek universe that Earth helped to develop. This indicates that the United States’ role in WWII was seen as so significant that without their actions there would have been repercussions for the entire universe that lasted into the 23rd century. Additionally, this helps to rationalize America’s use of atomic weapons in the Second World War by claiming that if the United States did not develop and utilize the bomb, there was a risk of Germany doing so first and destroying the free world.

Themes and commentary in “The City on the Edge of Forever” can be compared to the 1995 Star Trek: Deep Space Nine two-part episode “Past Tense” to demonstrate evolving perspectives regarding social and welfare programs between the decades. In the episode, space station Deep Space 9’s Commander Benjamin Sisko, Lt. Commander Jadzia Dax, and Doctor Julian Bashir were accidentally sent to San Francisco in August of 2024 to a watershed moment in Earth’s history.[30] In this fictional imagining of the future, cities across the United States isolated “undesirable citizens” like the mentally ill, unemployed, and poor from the rest of society in locked “sanctuary districts” that were utilized as a method of enforced social control, similar to ghettos. Sisko and Bashir were placed into one of these districts, where they were quickly accosted by a group of other residents who wanted to steal their food ration cards. The ensuing fight resulted in the death of another resident, Gabriel Bell, when he attempted to help protect Sisko and Bashir. Bell was a fictional historical figure from 2024 who was famous for protecting hostages that were taken during a violent protest orchestrated by the residents who attacked Sisko and Bashir, and who took advantage of the situation to call attention to the grim reality of the sanctuary districts. In order to preserve the timeline, Sisko assumed Bell’s identity to fulfill his role in the hostage crisis and ensure that national legislation outlawing the districts was enacted. Through this plotline, the episode provides commentary on many different social issues, such as mass incarceration, welfare, unemployment, homelessness, and the mental health crisis caused by the deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals. This was a direct response to the Clinton administration’s 1992 campaign promise to change the welfare system and 1994 legislation that exacerbated the mass incarceration crisis, while also providing a response to pervasive social concerns that arose through actions taken by the Reagan Administration in the previous decade.

Character conversations and overarching plot in “Past Tense” provided commentary on Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign promise to “…end welfare as we know it…” and later legislation like the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Authorization Act of 1994, which implemented harsh sentencing minimums for certain crimes, especially those related to drugs, and aggravated the mass incarceration crisis in the United States.[31] In 1992, a Clinton campaign commercial described their goal to restructure the welfare system in order to add mandatory work requirements to “…break the cycle of welfare dependency,” and later resulted in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 which restructured federal welfare programs and implemented new requirements to receive assistance.[32] Furthermore, concern regarding rising crime rates in inner cities starting in the 1960s led to the development of new methods of calculating crime rates that subsequentially resulted in the American mass incarceration crisis that perpetuated socioeconomic consequences that increased the violent crime rate from 200.2 per 100,000 in 1965 to 684.6 per 100,000 in 1995.[33] The mass incarceration crisis was further compounded by the escalation of the deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals in the 1990s, which, according to a 2013 study in The Journal of Legal Studies, resulted in a 4-7% growth in incarceration rates between 1980 and 2000.[34] This caused a mental health crisis in the United States because of the lack of education regarding the treatment and care for people with mental illness and, consequentially, there was a disproportionate number of people with mental illness in the United States who were homeless. Law enforcement officers would often arrest these individuals for petty crimes and instances of indecent behavior in public spaces, and would them hold them in local jails to wait for psychiatric care.[35] These developments were reflected in “Past Tense” through the use of sanctuary districts to house the “undesired” citizens of the United States to the extent that overcrowding led to limited housing and resources which resulted in increased instances of organized violence within the districts.

Throughout the episode, Sisko, Dax, and Bashir frequently commented on issues of social injustice in the sanctuary district, both in private conversations and directly to the people who live in 2024. For example, while trying to find a place to sleep, Sisko and Bashir see a man wrapped in a blanket sitting on the street, who appeared to be hallucinating, and proceed to have a discussion regarding the general ambivalence they observed towards the suffering in the sanctuary districts:

Bashir: There’s no reason for him to live like that…they could cure that man now, today if they gave a damn.

Sisko: …it’s not that they don’t give a damn, it’s that they’ve just given up. The social problems that they face are too enormous to deal with.

Bashir: …that only makes things worse. Causing people to suffer because you hate them is terrible but causing them to suffer because you’ve forgotten how to care – that’s really hard to understand.[36]

When taken in the context of the welfare crisis of the period, especially given Clinton’s campaign promises to limit welfare access, this conversation provides commentary on legislation that targeted and incarcerated minority populations for drug based crimes and welfare fraud in addition to incarcerating people with mental illness rather than providing them with psychiatric care.[37] This resulted in the development of a system that punished rather than rehabilitated, perpetuating social injustice without an attempt to find a solution by ignoring and targeting people seen as unworthy of help subsequentially increasing the stigma towards receiving welfare assistance in the United States.

The critique of the United States in the show is further emphasized throughout the two-part episode through the interactions of characters from 2024 with the main cast. Contemporary characters commented on the injustice of their situation and expressed frustration with their inability to change the system. For example, the government worker at the sanctuary district who processed Sisko and Bashir’s paperwork, described the systematic bias of the sanctuary districts based on the categorization of people and defines the pejorative slang terms, gimmes and dims, used to describe the groups: “Gimmes are…people who are looking for help. A job, a place to live…the dims should be in hospitals, but the government can’t afford to keep them there, so we get them instead. I hate it, but that’s the way it is.”[38] The worker, Lee, was later taken as one of the hostages and her critical sentiment towards the sanctuary districts was further emphasized in a conversation with Bashir. She described an incident when she first started working for the sanctuary district where she was almost fired after she processed a woman who had an arrest warrant for the crime of child abandonment. She discussed how the woman left her son with the family that previously employed her, because she could not take care of him, further revealing that:

Lee: I felt so sorry for her. I didn’t log her in, I just let her disappear into the Sanctuary.

Bashir: Well, that was very kind of you…what happened to this woman?

Lee: I don’t know, but I think about her all the time. Ever since then I’ve just done my job, you know? Tried not to let it get the best of me.

Bashir: It’s not your fault that things are the way they are.

Lee: Everybody tells themselves that, and nothing ever changes. [39]

This conversation provides metacognitive analysis on the pervasive feelings of dread and inadequacy that the average American experienced regarding social injustice and their inability to change their role in the perpetuation of a system of oppression. Any aspect of American exceptionalism reflected in “Past Tense” through long term influence of the United States in the forming of the Federation that was displayed through Sisko, Dax, and Bashir’s intervention in the past, is negated through the way that characters blatantly criticized the system in addition to the implication that their intervention into the status quo was necessary for the correct future to occur.[40] This means that the episode does not function as an example of victory culture and, as a result, American exceptionalism is subsequently not evident in this episode to the same extent as it was in “The City on the Edge of Forever,” which lacked the larger criticism of social injustice seen in “Past Tense.” Through their active intervention to change the status quo, Sisko, Dax, and Bashir were able to integrate themselves into the past in a way that Kirk and Spock did not by ensuring Keeler died to prevent the Nazis from winning World War II.

While there are themes of American exceptionalism in “The City on the Edge of Forever,” in the way that it highlighted the social progress of the 1960s, the critical themes in “Past Tense” towards the sociopolitical decisions of the era demonstrate a disillusionment with the institution of the United States. Furthermore, the time periods that the characters traveled to are also significant when analyzing commentary in each series. In The Original Series, Kirk and Spock go back in time to the 1930s, a retrospective point in history that was seen as one of the darkest periods in living memory. This is contrasted in Deep Space Nine, with Sisko, Dax, and Bashir traveling back in time a prospective dark future in 2024 which was created by the writers. By focusing the episode on a dark lived point in history, the writers of The Original Series highlighted the exceptionalism of the 1960s through contrast with the Great Depression, creating an example of social reform-based victory culture. Comparatively in Deep Space Nine, the writers portrayed a negative view of the United States through the creation of a fictional point in the near future where social divisions were heightened to the extent that society was on the verge of collapse, as a result of the actions taken by the American government. This episode provides critique by the writers regarding the sociopolitical failings of the 1990s and functions as a call to action regarding their desire to see social change enacted in order to prevent the possibility of the future that they described in “Past Tense,” which is contrary to the themes of social stagnation seen in “The City on the Edge of Forever” that emphasized the exceptional progress of the 1960s.

War, Terrorism, and Violence

After the end of the Second World War, the United States had to reconcile their new status as the world’s only remaining stable superpower, which manifested through their increased involvement in conflicts in both the Middle East and previously Soviet dominated regions. The other defining political development of the second half of the twentieth century was the Cold War, which permeated every aspect of American sociopolitical and personal life and heightened internal tensions in the United States. The 1960s were a turbulent point in history as a result of the Cold War, especially regarding the ensuing military conflicts in Korea and Vietnam that were waged in an attempt to prevent the spread of communism. During the Vietnam War, there was a disillusionment with the United States because of American involvement in what was perceived to be a useless and never ending conflict. The legacy of the Vietnam War defined perspectives regarding the increasing involvement of the United States military in the affairs of other countries like Somalia, Haiti, and the Balkans in the 1990s.[41] This was evident through varying perceptions of the American declared victory in Operation Desert Storm of the Persian Gulf War in 1991, particularly when President Bush claimed that the negative legacy of the Vietnam War was over and called for a “new world order” where countries worked together to protect freedom, security, and the rule of law.[42]

Another major concern between the 1960s and 1990s was an increase in instances of terrorism in the United States. One example was the heightened threat of international aviation terrorism from the 1960s through the 1980s with saboteurs hijacking or destroying planes to gain political leverage and provide propaganda for their causes.[43] Furthermore, 1970 had the highest number of terrorist attacks recorded by the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), with more than 460 instances in the year alone, before rates steadily declined throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[44] The increasing sociopolitical divide in the United States further resulted in acts of violent domestic terrorism such as the attacks by the left-wing extremist group the Weather Underground who were credited with at least 25 bombings between 1974 and 1978, the Unabomber who killed three people and injured 23 others between 1978 and 1995, and the Oklahoma City Bombing in 1995 that killed 168 people and injured hundreds of others.[45] Furthermore, the 1993 World Trade Center Bombing by Islamic fundamentalist extremists associated with Al-Qaeda resulted in a 100-foot crater in the building that killed six people and injured more than one thousand others.[46] This was accomplished by the perpetrators hiding a bomb in the parking garage under the towers with the intent to completely destroy them, a goal which was later completed by Al-Qaeda on September 11, 2001, and had planned a series of plane bombings at the time. Importantly, fear of domestic and foreign terrorism increased exponentially in the wake of the Oklahoma City Bombing in 1995 by American white nationalists Timothy McVey and Terry Nichols, which led to new legislation under the Clinton Administration in 1996 that made terrorism a federal crime, gave funding to federal agencies, and made it easier to deport people who entered the country illegally.[47]

Historians H. Bruce Franklin and Nicholas Evan Sarantakes wrote about how the Cold War and the United States’ involvement in Vietnam were two of the most influential current events represented in Star Trek: The Original Series. Franklin examined select episodes that aired between 1967 and 1969, to demonstrate how they directly related to the Vietnam War.[48] He established that the episodes reflected the United States’ evolving perspective on the war based on how the first two episodes examined presented the war as a necessary evil, while the last two represented the desperation of the era and called for radical change, namely an end to the Vietnam War. Similarly, Sarantakes argued that the Original Series used cinematic allegory to comment on contemporary politics and foreign policy as a way to express the role the writers believed the United States should play in world politics. [49] He accomplished this by highlighting the intentional allegorical comparison of political prowess and the capitalist and communist powers during the Cold War in The Original Series.

Fear in response to of the threat of national and international violence was pervasive in the American consciousness during the 1960s and 1990s. Many episodes in The Original Series had plots that included violence and combat, but there was never an active war. The show did include Cold War inspired plots through the Federation’s ongoing political conflicts with the Romulan and Klingon Empires, which were known to result in minor skirmishes and attempted acts of terrorism such as in the episode “The Trouble with Tribbles.” Furthermore, it is important to note that the conflict with the Romulans was not introduced until the 14th episode and the hostilities with the Klingon Empire did not begin until the 26th episode. The battles between the Federation and these empires were generally isolated to single episodes rather than longer overarching season-long plots. During the 1990s, the number of white supremacist organizations and anti-government militias in the United States was increasing.[50] As a result, Deep Space Nine provided commentary on the mounting examples of political terrorism through the Bajoran religious ideological conflict. Furthermore, the heightened involvement of the United States military in foreign nations was indirectly criticized through the demonstration of the futility of combat and the psychological impacts of war on young civilians and soldiers, specifically through the characters of Jake Sisko and Ensign Nog. These episodes served to comment on the lingering effects of combat on the physical and mental wellbeing of soldiers and civilians in addition to counteracting the perceived glory of combat by presenting protagonists committing morally dubious acts in battle.

The interactions between the Klingons and the Federation were grounded in racist stereotypes and ideological differences rather than active battle-driven hatred. In the episode “The Trouble with Tribbles,” the crew of the USS Enterprise came into contact with a group of Klingon soldiers while on shore leave, who provoked a fight with the Starfleet officers by calling the captain and the Enterprise derogatory names, which resulted in a bar brawl led by the Chief Engineer and the Head Navigator. [51] This altercation exemplified the ideological basis and contemptuous nature of the Klingon-Federation conflict. The episode provided further commentary on the Cold War through the discovery of a Klingon spy on the K-7 space station, who poisoned grain stores in an attempt to allow the Klingon Empire to gain full control of the planet the station was orbiting by killing all of the Federation colonists. This attempted act of sabotage was discovered by the crew of the Enterprise and did not result in a war between the Federation and the Klingon Empire. However, the discovery of a Klingon infiltrator who was physically altered to look human and was acting as the aide to a Federation undersecretary, highlights themes of American exceptionalism because the crew of the USS Enterprise was able to identify and neutralize this enemy, thus preventing civilian deaths and a war with the Klingons. This is reflective of the omnipresent fear that communist insurgents were infiltrating the United States government during the Cold War for nefarious purposes.[52] As a result, the episode functions as an example of victory culture that emphasized the moral superiority and successes of the Federation, who represented the United States, by rooting out traitors in comparison to the failed attempt of deceit by the Klingons who acted as an allegory for a communist nation.

A preeminent example of commentary on terrorism in Deep Space Nine is in the episode “In the Hands of the Prophets,” where a religious fanatic bombed a school on the Deep Space 9 station.[53] This attack was motivated by a federation teacher referring to the Bajoran gods as “entities” while employing a purely scientific perspective during her lesson, rather than using terminology that aligned with the Bajoran faith. This situation instigated debate regarding the content children should be taught given that Deep Space 9 was technically a Bajoran station, and whether the Bajoran and Federation children should receive the same education or even attend the same school. This eventually escalated to a bomb being detonated in the school as a message to the teacher, and ultimately led to an assassination attempt against Vedek Bareil, a progressive religious leader who was the most likely candidate to become the next head of the Bajoran religion. It is heavily implied that the orthodox sect leader, Vedek Winn, orchestrated the bombing in order to stage the assassination attempt against Vedek Bareil and prevent him from becoming the Kai of Bajor.[54] The violence in this episode reflected the threat felt in the United States from far right domestic terrorism in recent decades, especially regarding the fear for the safety of civilians and children. Additionally, the religiously motivated school bombing in this episode serves as allegory for the religiously motivated bombing of the World Trade Center by Islamic fundamentalists associated with Al-Qaeda in February 1993, four months before this episode aired, that resulted in the deaths of six people and the injuries of over one thousand others.[55] The success of the station’s crew in thwarting the assassination attempt can be interpreted as an example of exceptionalism, but the underlying implications regarding the motivations behind the incident emphasize the instability of politics by highlighting violent ideological conflict in a manner that vilifies conservative extremism. Furthermore[HB1] , the episode demonstrates the fragile relationship between the Bajoran and Federation residents on the Deep Space 9 stationat the beginning of the series in a manner that depicts the Federation citizens as outsiders and interlopers, because they were imposing their values onto the Bajoran children, ultimately undermining any American exceptionalist themes.

The central theme of war was pervasive throughout Deep Space Nine; the series began by exploring the consequences of the Federation defeat at the Battle of Wolf 359 and the occupation of Bajor by the Cardassians, and subsequentially concluded with the Federation victory in the Federation-Dominion War.[56] The commentary on war in the series was largely accomplished by portraying youth experiencing battle and exploring the psychological impacts of combat through the experience of Jake Sisko in “…Nor the Battle to the Strong” and Nog in “The Siege of AR-558” and “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” These episodes emphasized the disillusionment with the United States and the decreasing view of war as exceptional, through the changing perspective of each character regarding the glory of battle as a direct result of their experiences. This was further accomplished by including multiple examples of violence through plots centered on both terrorism and military conflict in the series in addition to the presentation of immoral actions taken in combat by the Federation soldiers in the name of survival.

In “Nor the Battle to the Strong,” Jake Sisko, son of Deep Space 9’s Commander Benjamin Sisko, was an 18 year old civilian who accompanied Dr. Julian Bashir to a medical conference with the intention of writing a news article about him.[57] However, when Dr. Bashir was diverted from the medical conference to a field hospital because of an attack by the Klingons, Sisko willingly entered the battlefield with the intention of detailing the glory of combat.[58] When he encountered armed conflict and death, Sisko struggled to reconcile the violence that he experienced with his preconceived notions of the grandeur of war. He witnessed multiple people die in gruesome ways, vomits in reaction to Bashir’s macabre gallows humor about surgery, and fled combat multiple times. For example, when Sisko and Bashir attempted to retrieve a power generator from their ship, they were pinned down by shelling which caused Sisko to run away, leaving an unconscious Bashir behind. This was contrasted by his actions at the end of the episode, where Sisko unintentionally caused their base’s entrance to collapse by blindly shooting into the air to protect himself from advancing Klingons. Sisko’s actions provided the medical team with enough time to safely evacuate the patients in the field hospital, which resulted in Bashir labeling him a “hero.” When Sisko ultimately wrote the article detailing his experiences, he discussed the futility of the battle in the context of greater history, and the impact that it had on his life.

More than anything I wanted to believe what he was saying but the truth is I was just as scared in the hospital as I’d been when we went for the generator, so scared that all I could think about was doing whatever it took to stay alive. Once that meant running away and once it meant picking up a phaser. The battle of Ajilon Prime will probably be remembered as a pointless skirmish but I’ll always remember it as something more – as the place I learned that the line between courage and cowardice is a lot thinner than most people believe.[59]

This quote demonstrates the harmful psychological impact of war and the futility of combat in a time where there was increased threat of the United States entering a global conflict in the Middle East. It also portrayed the decreasing exceptionalism associated with combat by the American populace, through emphasis on the reality of fear and cowardice rather than the historical glorified view of combat seen in examples of media that highlighted America’s exceptionalism through military victory culture.

The fact that the Federation’s war with the Klingons seen in this episode was caused by the infiltration of enemies into the Klingon government via shapeshifters in addition to the conflict being the result of the violation of a cease fire, makes this equally as analogous with terrorism as war. This conflict provided commentary on both the threat of active war and the rise in hate groups and violent protests in the mid-1990s and the subsequent Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, passed by the Clinton Administration.[60] Sisko’s experiences in the episode demonstrate a primal, emotional response to war, even if he had indirectly experienced combat on Deep Space 9 and in the Battle of Wolf 359 as a child. Detailing the experiences of a protagonist who responded to combat in dishonorable and realistic ways further emphasized the lack of American exceptionalism in the 1990s in the wake of increased violence and the threat of terrorism.

In addition to commentary on the psychological effects of combat on civilians through Jake Sisko, Deep Space Nine provided analysis regarding the experiences of young soldiers through Ensign Nog in “The Siege of AR-558.” The episode took place during the War with The Dominion, an empire from the Gamma Quadrant that was trying to destroy the Federation.[61] Captain Sisko brought a group of officers from Deep Space 9, including Ensign Nog of Starfleet and his uncle Quark, who was acting as a representative of the Ferengi Alliance, to deliver supplies to a battalion of Federation soldiers who had taken control of a Dominion communications tower.[62] The 43 surviving Starfleet officers, out of the original 150 stationed at the communications tower, had been pinned down for five months. This was significantly longer than the 90 day maximum deployment mandated by Starfleet and meant that they were experiencing severe battle fatigue that had resulted in infighting among the officers.

Captain Sisko eventually commanded Nog to participate in a small scouting party to determine the number of Dominion Jem’Hadar soldiers encamped nearby.[63] Quark tried to persuade his nephew to stay at the base, but Nog rebuffed his attempt based on his sense of duty as a Starfleet officer and his need to prove himself as the first Ferengi in Starfleet in combination with his hero worship of the surviving officers at the base. While on the mission, they were ambushed by the Jem’Hadar and Nog was wounded, he was rushed back to the base for emergency medical attention, ultimately resulting in Dr. Bashir amputating his leg. During the battle, Quark and Nog remained in the base while the rest of the officers, including Dr. Bashir, engaged the Jem’Hadar. Prior to the battle, the officers were able to repurpose Dominion landmines and use them to slow the Jem’Hadar’s advance by putting them in the path between their encampment and the communications tower. This episode portrayed the cynicism of the 1990s towards the United States by having the protagonists repurpose and intentionally reprogram brutal enemy weapons to be triggered by movement with the intention of eliminating approximately one third of their enemy’s forces. The lack of glory in combat is evident in the episode through the Federation soldiers’ desperation overriding their moral objections to using the landmines in a desperate attempt to survive the battle.

In the episode “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” Nog returned to Deep Space 9 after an extended medical leave where he was fitted with a bio-synthetic leg and received psychological counseling.[64] However, it is revealed that Nog was still experiencing post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, and phantom limb pain that manifested in a psychosomatic limp which required him to use a cane. Nog also became obsessed with listening to the song “I’ll be Seeing You,” performed by the holographic character Vic Fontaine, because Dr. Bashir played the song for him while he was wounded during the battle. This led to Nog choosing to live in Vic’s holographic world for an extended period of time to recuperate and learn to cope with his experiences.[65] Vic helped Nog to reconcile some of his trauma, but he ultimately refused to leave the Holosuite. When Vic confronted Nog, he said:

When the war began…I wasn’t happy or anything, but I was eager. I wanted to test myself. I wanted to prove I had what it took to be a soldier, and I saw a lot of combat. I saw a lot of people get hurt. I saw a lot of people die. But I didn’t think anything was going to happen to me. And then, suddenly Dr. Bashir is telling me he has to cut my leg off. I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t believe it. If I could get shot, if I could lose my leg, anything can happen to me, Vic. I could die tomorrow. I don’t know if I’m ready to face that. If I stay here, at least I know what the future is going to be like.[66]

Nog was using a fantasy world to cope with the trauma of being wounded at the Siege of AR-558 but was ultimately unable to hide from reality forever. The psychological impact of war on young soldiers was a highly relevant topic in the wake of the Gulf War and with the increasing threat of United States involvement in a major conflict in the Middle East. Furthermore, the diminishing presence of victory culture in the 1990s is evident through the emphasis on the physical and psychological trauma of combat on soldiers. Nog’s injury as a result of his need to prove himself as a soldier emphasized the evolving American consciousness towards warfare and changing perception regarding the lack of glory in combat by highlighting the negative consequences of willingly entering war, even for soldiers who had trained for and previously experienced battle.

Jake Sisko and Ensign Nog provided two different examples of the exposure of young adults to combat in different contexts. Jake wanted to document the glory of battle as a reporter, while Nog joined Starfleet and felt dutybound to serve in the Dominion War as the first Ferengi officer, but still felt a sense of hero worship towards his fellow soldiers at the battle of AR-558 for their actions in combat. It is important to note that despite the fact that Jake was a civilian and Nog was an officer, both willingly entered battle in search of glory and were disillusioned by their experiences in spite of the fact that they had been previously exposed to conflict in some manner. These characters reflected the shifting mentality of the United States away from victory culture and American exceptionalism towards a disillusionment with the American institution as a whole. The commentary in the show differs from The Original Series through the overarching presence of violence in the series in addition to demonstrating the negative impact that war had on the young characters in the show. By including the aftereffects of combat, they were providing an increasingly realistic view of war that reflected the populace’s understanding of conflict, especially in the wake of the televised aspects of the Vietnam and Gulf Wars.[67]

Applications for the Social Studies Classroom and Conclusion

The 1990s were a transitional period between the mid-twentieth century and the grim future of the twenty-first. There was still a hopeful view of the future in the 1960s, which can be observed through the presentation of the characters in Star Trek: The Original Series despite the turbulence of the era. This was the result of lingering exceptionalist views of the nation in the wake of the Second World War which persevered during the ideological conflict of the Cold War inflating the United States’ sense of superiority. Contrarily in the 1990s, the general populace became disillusioned with the United States as an institution, culminating in a much darker view of the future in the series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. This change was caused by the shifting American consciousness to become actively critical of the widespread pervasive social conflict that disproportionally targeted disenfranchised populations and the heightened threat of violence in the United States after the end of the Cold War from terrorism and American involvement in foreign conflicts. Additionally, the overwhelming disillusionment with the United States by the general populace resulted in decreased examples of victory culture that depicted the exceptionalism of America in terms of their social and military achievements. By comparing social and political events from the time they were created to themes depicted in each show, the cynicism of the 1990s can be observed, especially when contrasted with the exceptionalist view of America in the 1960s.

Sociopolitical commentary and themes of violence in the Star Trek franchise can be examined to understand both the changing perception of the American populace and the rising tensions of the time in response to the increasing threat of war and violence at the end of the twentieth century. Commentary on major sociopolitical crises like mass incarceration, mental illness, and welfare can be observed through the reactions of major characters to their surroundings in time travel based episodes in addition to the actions of contemporary characters from the past. Furthermore, the increasingly negative view of combat in the 1990s can be observed by examining the presence of war throughout the entirety of Deep Space Nine and by exploring how the reactions of characters to violence mirrors contemporary developments regarding the threat of terrorism and war. This analysis furthers the examination of popular media commentary on sociopolitical conflict and the increasing threat of violence, which is especially significant in the context of understanding the influence of rapidly changing American media and determining the events that impacted the polarized political climate of the 2020s. Ultimately, this analysis demonstrates that historians can use science fiction shows, like the Star Trek franchise, as primary source relics to understand the zeitgeist of the era they were created, in spite of how they may appear disconnected from modern events due to their unrealistic setting. This paper demonstrates the significance of television to the study of cultural history as a result of its accessibility to the general public and the way that these shows provide commentary on current events, which reflects the public opinion of the general populace. This is especially true for the shows in Star Trek because of the unique opportunity for historical study presented by the way that the Star Trek franchise consists of various independent shows over multiple decades, which can be used to observe changing mentality of the United States. As a result, the declining American exceptionalism and view of the United States in the 1990s can be observed by examining different themes and plots in multiple series of the Star Trek franchise over time in order to determine the declining presence of victory culture in each era.

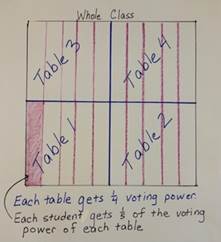

In the context of the social studies classroom, this research similarly demonstrates the ability of teachers to use science fiction media, including television series, to show students how historical perspectives are represented in popular culture. Film has been used in the classroom for decades given how engaging it is for students, and how consumable the medium is for students of all backgrounds and abilities as a way to visualize events, understand reactions to incidents, and scaffold conversation.[68] Science fiction has traditionally been a platform for writers to provide analogous commentary on their experiences and perceptions of current events, a quality that is abundantly clear in the Star Trek franchise. This genre has been used in order to portray fictionalized versions of historical events and ideas, which can be explored in the classroom by evaluating the representation of political themes and contemporary events in film and shows. The unique quality of the Star Trek series spanning multiple decades can be used in the classroom in order to demonstrate changing mentality regarding the current and public perception of the United States to students. As a result, teachers can use short clips or entire episodes in order to present the changing perspectives of the United States through this franchise in particular. Using this type of visual media will help students to understand the impact of decisions made during the contemporary era and will also help them to comprehend the impact of complex sociopolitical and military developments in the United States, such as mass incarceration, welfare, increased threat of terrorism, and the consequences of the end of the Cold War and Gulf War in the 1990s.

References

Primary sources

Behr, Ira Steven and Hans Beimler, writers. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 7, episode 8, “The Siege of AR-558.” Directed by Winrich Kolbe, featuring Avery Brooks, Aron Eisenberg, Armin Shimerman, and Alexander Siddig. Aired November 10, 1998, in broadcast syndication. https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/mIdm1LceoK_eeqS uaO8_jl7G_QNJuhi6/.

Behr, Ira Steven and Robert Hewitt Wolfe, writers. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 3, episode 11, “Past Tense, Part 1.” Directed by Reza Badiyi, featuring Avery Brooks, Terry Farrell, and Siddig El Fadil. Aired January 2, 1995, in broadcast syndication. https://www .paramountplus.com/shows/video/Y2jFFEXQw_2hrGX5mrGX90zqkzR4vi7G/.

Behr, Ira Steven, Robert Hewitt Wolfe, René Echevarria, writers. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 3, episode 12, “Past Tense, Part 2.” Directed by Jonathan Frakes, featuring Avery Brooks, Terry Farrell, and Siddig El Fadil. Aired January 9, 1995, in broadcast syndication. https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/X1Qfoe06ZqK3hdP4O8YYb bKGSHZ2tydI/.

Berke, Richard L. “THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: THE AD CAMPAIGN; Clinton: Getting People Off Welfare.” New York Times, September 10, 1992, A20. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/ 10/us/the-1992-campaign-the-ad-campaign-clinton-getting-people-off-welfare.html?smid =url-share.

Ellison, Harlan, writer. Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1, episode 28, “The City on the Edge of Forever.” Directed by Joseph Pevney, featuring William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley, and Joan Collins. Aired April 5, 1967, in broadcast syndication. https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/1179123511/.

Gerrold, David, writer. Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2, episode 15, “The Trouble with Tribbles.” Directed by Joseph Pevney, featuring William Shatner, James Doohan, and Walter Koenig. Aired December 29, 1967, in broadcast syndication. https://www.paramo untplus.com/shows/video/1226188697/.

Humphrey, Hubert H. “The War on Poverty.” Law and Contemporary Problems 31, no. 1 (1966): 6-17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1190526.

Mack, David, Ronald D. Moore, and John J. Ordover, writers. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 7, episode 10, “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” Directed by Anson Williams, featuring Avery Brooks, Aron Eisenberg, and James Darren. Aired December 30, 1998, in broadcast syndication. https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/C4tVIj7ZzLXaNyd 1NAVh71SEN85fkPP2/.

Parker, Brice R and René Echevarria, writers. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 5, episode 4, “…Nor the Battle to the Strong.” Directed by Kim Friedman, featuring Cirroc Lofton and Alexander Siddig. Aired October 21, 1996, in broadcast syndication. https://www.paramo untplus.com/shows/video/M0Jzs5X8tCYk_8WOjuCwArnwUfhMEsZD/.

“The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996.” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. US Department of Health and Human Services, August 31, 1996. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/personal-responsibility-work-opportunity-reconciliation-act-1996.

Wolf, Robert Hewitt, writer. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 1, episode 20,“In the Hands of the Prophets.” Directed by David Livingston, featuring Avery Brooks, Nana Visitor, Colm Meaney, Rosaland Chao, and Louise Fletcher. Aired June 20, 1993, in broadcast syndication. https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/gg7NOUqKNrbke8RtQxpzYx 9teVPy22Hz/.

Piller, Ira Michael and Rick Berman, writers. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 1, episode 1, “Emissary, Parts 1 and 2.” Directed by David Carson, featuring Avery Brooks, Terry Farrell, and Siddig El Fadil. Aired January 3, 1993, in broadcast syndication. https://www .paramountplus.com/shows/video/zbYJuXEpNDasxVJf48I7BRo3vg5ogjuF/.

Secondary Sources

“1993 World Trade Center Bombing,” Latest Stories, U.S. Department of State, February 21, 2019, https://www.state.gov/1993-world-trade-center-bombing/.

Arasly, Jangir. “Terrorism and Civil Aviation Security: Problems and Trends.” Connections 4, no. 1 (2005): 75-90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26323156.

Carrier, Jerry. A Long Cold War: A Chronology of American Life and Culture 1945 to 1991. New York: Algora Publishing, 2018.

Ceaser, James W. “The Origins and Character of American Exceptionalism,” American Political Thought 1, no. 1 (2012): 3-28. https://doi.org/10.1086/664595.

Cullen, Jim. From Memory to History: Television Versions of the Twentieth Century. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2021.

Doherty, Thomas. Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

Engelhardt, Tom. The End of Victory Culture: Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation. Rev. ed. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007.

Franklin, H. Bruce. “Star Trek in the Vietnam Era.” Film and History 24, no. ½ (1994): 36-46. https://doi.org/10.1353/flm.1994.a395002.

Hijiya, James A. “The Conservative 1960s.” Journal of American Studies 37, no. 2 (2003): 201-227. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875803007072.

Kennedy, David M. “What the New Deal Did.” Political Science Quarterly 124, no. 2 (2009): 251-268. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25655654.

Kohler-Hausmann, Julilly. “Welfare Crises, Penal Solutions, and the Origins of the ‘Welfare Queen.” Journal of Urban History 41, no. 5 (2015): 576-771. https://doi.org/10.1177/009 6144215589942.

Kruz, Kevin M. and Julian E. Zelizer. Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019.

McAndrews, Lawrence J. “Promoting the Poor: Catholic Leaders and the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964” Catholic Historical Review 104, no. 2 (2018): 298-321. https://doi.org/10.1 353/cat.2018.0027.

Miller, Erin. “Patterns of Terrorism in the United States, 1970-2013: Final Report to Resilient Systems Division, DHS Science and Technology Directorate.” National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), Department of Homeland Security, (2014): 1-27. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/OPSR_TP_T EVUS_Patterns-of-Terrorism-Attacks-in-US_1970-2013-Report_Oct2014-508.pdf.

Mui, Vai-Lam. “Information, Civil Liberties, and the Political Economy of Witch-Hunts.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 15, no. 2 (1999): 503-525. https://www.jstor. org/stable/3555065.

Nagl, John and Octavian Manea. “The Uncomfortable Wars of the 1990s.” In War, Strategy and History: Essays in Honour of Professor Robert O’Neill, edited by Daniel Marstonand Amara Leahy, 127-154. Canberra: Australia National University Press. https://www.js tor.org/stable/j.ctt1dgn5sf.15.

“Oklahoma City Bombing,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/oklahoma-city-bombing.

Raphael, Stephen and Michael A. Stoll. “Assessing the Contribution of the Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill to Growth of the U.S. Incarceration Rate.” The Journal of Legal Studies 42, no. 1 (2013): 187-333. https://doi.org/10.1086/667773.

Roiblatt, Rachel E. and Maria C. Dinis. “The Lost Link: Social Work in Early Twentieth‐Century Alcohol Policy.” Social Service Review 78, no. 4 (2004): 652-674. https://doi.org/10.1086 /424542.

Russell, William B., III. “The Art of Teaching Social Studies with Film.” The Clearing House 85, no. 4 (2012): 157-164, https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2012.674984.

Sarantakes, Nicholas Evan. “Cold War Pop Culture and the Image of U.S. Foreign Policy: The Perspective of the Original Star Trek Series.” Journal of Cold War Studies 7, no. 4 (2005): 74-103. https://doi.org/10.1162/1520397055012488.

Stoddard Jeremy D. and Alan S. Marcus. “More Than “Showing What Happened”: Exploring the Potential of Teaching History with Film.” The High School Journal 93, no. 2 (2010): 83-90. https://doi.org/10.1353/hsj.0.0044.

“The Unabomber,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/unabomber.

Thompson, Heather Ann. “Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History.” The Journal of American History 97, no. 3 (2010): 703-734. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/97.3.703.

Thomson, Irene Taviss. “Culture, Class, and American Exceptionalism,” in Culture Wars and Enduring American Dilemmas, 175-216. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2010.

Upton, Bryn. Hollywood at the End of the Cold War: Signs of Cinematic Change. London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014.

“Weather Underground Bombings,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/weather-underground-bombings.

Weinstein, Paul B. “Movies as the Gateway to History: The History and Film Project.” The History Teacher 35, no. 1 (2001): 27-48. https://doi.org/10.2307/3054508

“World Trade Center Bombing 1993,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/world-trade-center-bombing-1993.

[1] The Borg are a cybernetic collective in the Star Trek universe that are controlled by the Borg Queen, who conquer planets in order to steal their technology and forcibly assimilate different civilizations into their collective hive mind. Their ultimate goal is to achieve perfection by adding the knowledge and technologies of other civilizations to their own.

[2] Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, season 1, episode 1, “Emissary, Part 1,” directed by David Carson, written by Ira Michael Piller and Rick Berman, featuring Avery Brooks, Terry Farrell, and Siddig El Fadil, aired January 3, 1993, in broadcast syndication, 0:00-4:33, https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/zbYJuXEpNDasxVJf48I7BRo3v g5ogjuF/. Siddig El Fadil changed his name to Alexander Siddig in 1995, which was reflected in the show starting in season 4, episode 1.

[3] Star Trek: Deep Space Nine chronicles events on the space station Deep Space 9. The stationorbits the planet Bajor, a non-Federation planet that was working to achieve Federation membership, resulting in both Bajoran and Federation officers onboard, and is commanded by Federation Commander (later Captain) Benjamin Sisko with Bajoran first officer Major (later Colonel) Kira Nerys. The station’s significance is its location next to a stable wormhole that connects the Federation in the Alpha Quadrant to the otherwise unreachable Gamma Quadrant. The wormhole is also home to an alien species that exists outside of time who the Bajoran people identified as their gods that they named the Prophets. For the duration of this paper, Deep Space Nine will refer to the title of the show while Deep Space 9 will refer to the station in the series.

[4] Star Trek: The Original Series details the adventures of the crew of the starship USS Enterprise, led by Captain James Kirk. The original pilot of Star Trek: The Original Series, “The Cage,” will only be considered through the flashbacks incorporated into the two part episode “The Menagerie” given that it was not released in its entirety until 1988.

[5] James W. Ceaser, “The Origins and Character of American Exceptionalism,” American Political Thought 1, no. 1 (2012): 3-28, https://doi.org/10.1086/664595. Irene Taviss Thomson, “Culture, Class, and American Exceptionalism,” in Culture Wars and Enduring American Dilemmas (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2010): 181-187.

[6] It is important to note that there is a production period for television shows that results in a delay between contemporary events and the release of episodes that provide commentary on those events. For the sake of this analysis, commentary on specific events is considered within a time frame of approximately six months to a year before an episode is aired. However, there are also larger themes, concerns, and ongoing conflicts analyzed in this paper that impact public opinion which are considered within the context of the entire decade and do not follow the same time frame restrictions as specific dated events.

[7] Kevin M. Kruse and Julian E. Zelizer, Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974 (W. W. Norton & Company, 2019), 1-8.

[8] Tom Engelhardt, The End of Victory Culture: Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation, Rev. ed., (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), 3-15.

[9] Thomas Doherty, Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003): 4.

[10] Doherty, 2, 15-18.

[11] Jim Cullen, From Memory to History: Television Versions of the Twentieth Century, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2021), 1-15.

[12] Bryn Upton, Hollywood at the End of the Cold War: Signs of Cinematic Change, (London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), 1-15.

[13] Upton, 171-176.

[14] Jeremy D. Stoddard and Alan S. Marcus, “More Than “Showing What Happened”: Exploring the Potential of Teaching History with Film,” The High School Journal 93, no. 2 (2010): 83-90, https://doi.org/10.1353/hsj.0.0044; Paul B. Weinstein, “Movies as the Gateway to History: The History and Film Project.” The History Teacher 35, no. 1 (2001): 27-48, https://doi.org/10.2307/3054508; and William B. Russell III, “The Art of Teaching Social Studies with Film The Clearing House 85, no. 4 (2012): 157-164, https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2012.674984.

[15] Kruse, 113-122.

[16] Kruse, 180-222.

[17] David M. Kennedy, “What the New Deal Did,” Political Science Quarterly 124, no. 2 (2009): 253-254, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25655654.

[18] Heather Ann Thompson, “Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History,” The Journal of American History 97, no. 3 (2010): 706, 731-733, https://doi.org/10.109 3/jahist/97.3.703.

[19] Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, “Welfare Crises, Penal Solutions, and the Origins of the ‘Welfare Queen,’” Journal of Urban History 41, no. 5 (2015): 757, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144215589942.

[20] Stephen Raphael and Michael A. Stoll, “Assessing the Contribution of the Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill to Growth of the U.S. Incarceration Rate,” The Journal of Legal Studies 42, no. 1 (2013): 190, https://doi.org/10.1 086/667773.

[21] Kruse, 234-235.

[22] The episode began with the ship’s doctor, Leonard McCoy, accidentally injecting himself with a medication that caused acute psychosis. In his delusional state, he teleported to a nearby planet and when the captain and command crew went to rescue him, they encountered the Guardian of Forever, an entity that controlled a gateway to any moment in history. McCoy jumped through the portal to the year 1930 resulting in the erasure of the universe as they knew it. Captain Kirk and Commander Spock followed him back in time to retrieve McCoy and preserve the proper timeline.

[23] Star Trek: The Original Series, season 1, episode 28, “The City on the Edge of Forever,” directed by Joseph Pevney, written by Harlan Ellison, featuring William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley, and Joan Collins, aired April 5, 1967, in broadcast syndication, 22:04-23:08, https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/117912351 1/.

[24] Rachel E. Roiblatt and Maria C. Dinis, “The Lost Link: Social Work in Early Twentieth‐Century Alcohol Policy,” Social Service Review 78, no. 4 (2004): 652-654, https://doi.org/10.1086/424542.

[25] Roiblatt 661-666.

[26] Hubert H. Humphrey, “The War on Poverty,” Law and Contemporary Problems 31, no. 1 (1966): 6-7, https://doi.org/10.2307/1190526.

[27] Humphrey, 8.

[28] James A. Hijiya, “The Conservative 1960s,” Journal of American Studies 37, no. 2 (2003): 222-223, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875803007072.

[29] “Lawrence J. McAndrews, “Promoting the Poor: Catholic Leaders and the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964,” Catholic Historical Review104, no. 2 (2018): 319, https://doi.org/10.1353/cat.2018.0027.

[30] While trying to teleport from their ship, the USS Defiant, to Earth, Commander Benjamin Sisko, Lt. Commander Jadzia Dax, and Doctor Julian Bashir were accidently sent to their destination, San Francisco, but at a different point in time. While they tried to get back, they accidently altered the timeline and needed to fix it on their own while they waited for the rest of their crew to figure out how to rescue them.

[31] Richard L. Berke, “THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: THE AD CAMPAIGN; Clinton: Getting People Off Welfare,” New York Times, September 10, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/10/us/the-1992-campaign-the-ad-campaign-clinton-getting-people-off-welfare.html, and Kruse, 235.

[32] Berke, “1992 Campaign,” and “The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services, August 31, 1996, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/personal-responsibility-work-opportunity-reconciliation-act-1996.

[33] Thompson, 727-729.

[34] Raphael 219.

[35] Raphael, 191.

[36] Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, season 3, episode 11, “Past Tense, Part 1,” directed by Reza Badiyi, written by Ira Steven Behr and Robert Hewitt Wolfe, featuring Avery Brooks, Terry Farrell, and Siddig El Fadil, aired January 2, 1995, in broadcast syndication, 22:23-24:10, https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/Y2jFFEXQw2hrGX5mr GX90zqkzR4vi7G/ .

[37] Kohler-Hausmann, 766.

[38] “Past Tense, Part 1,” 19:42-19:59.

[39] “Past Tense, Part 2,” 20:22-

[40] In the episode, it is revealed that Starfleet and the Federation ceased to exist in the future after Gabriel Bell was killed.

[41] John Nagl and Octavian Manea, “The Uncomfortable Wars of the 1990s,” in War, Strategy and History: Essays in Honour of Professor Robert O’Neill, ed. Daniel Marstonand Amara Leahy (Canberra: Australia National University Press, 2016), 149, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1dgn5sf.15.

[42] Kruse, 184-187.

[43] Jangir Arasly, “Terrorism and Civil Aviation Security: Problems and Trends,” Connections 4, no. 1 (2005): https://www.jstor.org/stable/26323156.

[44] Erin Miller, “Patterns of Terrorism in the United States, 1970-2013: Final Report to Resilient Systems Division,

DHS Science and Technology Directorate,” National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), Department of Homeland Security, (2014): 9, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publicatio ns/OPSR_TP_TEVUS_Patterns-of-Terrorism-Attacks-in-US_1970-2013-Report_Oct2014-508.pdf.

[45] “Weather Underground Bombings,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/weather-underground-bombings.; “The Unabomber,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/unabomber.; and “Oklahoma City Bombing,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/oklahoma-city-bombing.

[46] “World Trade Center Bombing 1993,” History: Famous Cases and Criminals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/world-trade-center-bombing-1993, and “1993 World Trade Center Bombing,” Latest Stories, U.S. Department of State, February 21, 2019, https://www.state.gov/1993-world-trade-center-bombing/.

[47] Kruse, 220-221.

[48] H. Bruce Franklin, “Star Trek in the Vietnam Era,” Film and History 24, no. ½ (1994): 36-46, https://doi.org/10.1353/flm.1994.a395002.

[49] Nicholas Evan Sarantakes, “Cold War Pop Culture and the Image of U.S. Foreign Policy: The Perspective of the Original Star Trek Series,” Journal of Cold War Studies 7, no. 4 (2005): 74-103, https://doi.org/10.1162/1520397055 012488 .

[50] Kruze, 220.

[51] Star Trek: The Original Series, season 2, episode 15, “The Trouble with Tribbles,” directed by Joseph Pevney, written by David Gerrold, featuring William Shatner, James Doohan, and Walter Koenig, aired December 29, 1967, in broadcast syndication, 21:43-25:57, https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/video/1226188697/.

[52] Vai-Lam Mui, “Information, Civil Liberties, and the Political Economy of Witch-Hunts,” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 15, no. 2 (1999): 503-504, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3555065.