Teaching about the Indigenous Population of North America

Lessons by Alexandria Neely, Nicholas Zimmerman, and April Francis-Taylor

This package includes four lesson ideas with activity sheets that can be adapted for middle or high school.

The first lesson examines factors that influenced the migration and settlement of indigenous peoples across North America and different theories explaining the path of migration. The second lesson examines governance of different indigenous nations and their interaction with neighboring peoples. It also introduces the impact of geography on history and culture. Lesson three discusses the arrival of Norse Vikings and their interaction with the Mi’kmaq. Lesson four engages students in a discussion of “discovery” by European explorers.

LESSON 1: What factors influenced the migration and settlement of indigenous peoples across North America?

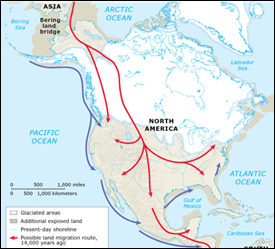

This lesson will be the first among three lessons covering the migration of early humans to the Americas, and their subsequent interactions between neighboring tribes and early-Europeans. Students will explore different theories about early human migration, how early humans arrived in the Americas, where they settled, and the impact of geography on their settlement and lifestyle patterns. It was believed that 13,000 years ago, early-humans traveled to the America’s via the Bering Land Bridge, a now-submerged geographical landmark that connected Northeastern Asia with Northwestern Alaska. However, in recent decades, researchers have discovered the remains of early humans in the Americas dating to 16,000 years ago possibly before access via the Bering Land Bridge was available. After collaborative research on migration theories, students will write an argumentative essay illustrating their stance on which theory best explains the evidence. Students will locate difficult vocabulary contained within the research articles and define terms. Enduring issues and unifying themes include the Impact of Environment on Humans; Population Growth; Impact of Technology.

CONTENT VOCABULARY:

Homo sapiens: Modern humans

Bering Land Bridge: Land that connected Asia and Alaska that was submerged when glaciers melted and sea levels rose.

Clovis people: Possible first human s to migrate from Asia to the Americas.

Clovis-First Theory: Belief that no humans lived in the Americas prior to approximately 13,000 years ago.

Artifact: Items made by human beings that provide clues to the past.

Migration: Movement of people across boundaries to new areas.

ACTIVITIES:

Video: “America Unearthed, Proof of Ancient Voyagers to America” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvqANniyRzI ), from the 30:00 time stamp, to the 32:00 time stamp.

The First Native Americans

A. “The Kennewick Man”: On July 28, 1996, two men at Columbia Park in Kennewick, Washington, accidentally found part of a human skull on the bottom of the Columbia River, about ten feet from shore. Later searches revealed a nearly complete, ancient skeleton, now known as “The Ancient One” or “Kennewick Man.” Public interest, debate, and controversy began when independent archaeologist Dr. James Chatters, working on contract with the Benton County coroner, thought that the bones might not be Native American. He sent a piece of bone to a laboratory to be dated. The results indicated an age older than 9,000 years, making The Ancient One among the oldest and most complete skeletons found in North America. Subsequent research on the bones indicated that the skeleton is between 8,400–8,690 years old.

Questions

1. Who is the Kennewick Man?

2. Why is the discovery of the Kennewick Man significant?

3. In your opinion, how did Kennewick Man arrive in North America?

B. On the timeline of history, the Clovis people appeared out of nowhere and disappeared in the blink of an eye. Archaeologists revealed that the Clovis had a pretty short existence: They first appeared in America around 9,200 B.C. and vanished 500 years later, around 8,700 B.C. So where did the Clovis come from and where did they go? Intense investigation into clues the Clovis left behind was launched as more artifacts were discovered. The Clovis-First Theory proposes that these people arrived in North America, from Siberia, where hunter-gatherer tribes lived.

(Source: Were the Clovis the first Americans? | HowStuffWorks)

Questions

1. According to the text, how long were the Clovis people present in North America?

2. In your opinion, why did the Clovis people migrate to North America?

C. Native Americans — like all humans—are descendants of the first humans, who lived and evolved over millennia in Africa. Though it is unclear when some of the first humans left the continent, evidence suggests that their migration out of Africa occurred approximately 200,000 years ago, gradually populating parts of the middle east, Europe and Asia. The arrival of humans into North America is believed to have occurred between 45,000 to 25,000 ago, the same time other groups of humans migrated into new territories including Australia and East Asian Pacific islands. We can’t be sure of the exact reasons humans first migrated off of the African continent, but it is likely the reason was a depletion of resources like food in their regions and competition for those resources.

(Source: Homo sapiens & early human migration (article) | Khan Academy.)

Questions

1. When does the author of this article claim humans began migrating to North America?

2. Why did humans migrate out of Africa and across the globe?

3. Using the map, how do you think humans migrate to North America?

D. Beginning in the early 1800s, American scientists and naturalists began to speculate about the ways early humans arrived in the Americas. However, it wasn’t until the mid-1920s that scientists determined

that towards the end of the Ice Age, the Earth experienced a long period of frigid [below-freezing] conditions. Glaciers formed in the northern region of the Earth. As more of the Earth’s water got locked up in the glaciers, sea levels dropped. In some areas it dropped up to 300 feet. The land beneath the Bering Strait, a waterway separating Asia and North America was exposed and a flat grassy treeless plain emerged. This exposed land is known as the Bering Land Bridge.

Questions

1. What impact do you think the glaciers had on early human migrations?

2. In your opinion, do you think that the Bering Land Bridge was the only way early humans could travel to the Americas?

E. Student teams will examine two other proposed explanations for human migration into North America.

The Pacific Coast Migration Model is a theory concerning the original colonization of the Americas that proposes that people entering the continents followed the Pacific coastline, hunter-gatherer-fishers traveling in boats or along the shoreline and subsisting primarily on marine resources.

https://www.thoughtco.com/pacific-coast-migration-model-prehistoric-highway-172063

The Solutrean hypothesis suggests that Neolithic fishermen and hunters from Northern Europe sailed the Atlantic in tiny boats made of animal skins 18,000 years ago and colonized the eastern United States.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/1999/nov/28/archaeology.uknews

Exit Ticket: What factors enabled early humans to migrate and settle in regions across North America?

LESSON 2. What types of interactions did Native Americans have with neighboring communities?

Indigenous tribes in America formed complex, successful societies like the Iroquois Confederacy, and created governing structures and agreements such as the Great Law of Peace. Depending on their location, different indigenous tribes had vastly different power structures, houses, foods, and lifestyles. Students will determine central ideas; provide an accurate summary of the purpose and definition of the Great Law of Peace and the Iroquois Confederacy. Enduring issues and unifying themesincludeImpact of Environment on Humans and Power.

CONTENT VOCABULARY:

Sedentary: the practice of living in one place for a long time.

Nomadic: the movement of a person or people from one place in order to settle in another.

Iroquois Confederacy: Confederation of six tribes across upper New York that played a major role in the struggle between the French and British for control over North America.

COMPELLING QUESTIONS:

- Why do you think is it important to learn about different tribes from all over what is now the United States?

- Why do you think the Founding Fathers only adopted some aspects of the Great Law of Peace into their writings? Which parts did they leave out? Why do you think they did?

- How does geography currently affect the way we live? How do you think it could affect us in the future?

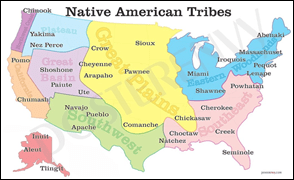

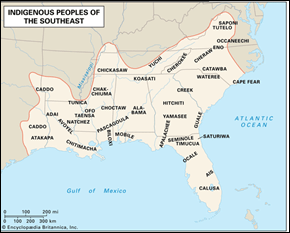

- Map of Indigenous people in the Territorial United States

Questions

- Which groups on the map have you heard of before? What do you know about them?

- Which groups are closest to where you live?

- How could their location influence their way of life? Give examples.

- How do you think these groups of people could have interacted with each other?

- Iroquois Confederacy

a. “The Peacemaker story of Iroquois tradition credits the formation of the confederacy, between 1570 and 1600, to Dekanawidah (the Peacemaker), born a Huron, who is said to have persuaded Hiawatha, an Onondaga living among Mohawks, to advance “peace, civil authority, righteousness, and the great law” as sanctions for confederation. Cemented mainly by their desire to stand together against invasion, the tribes united in a common council composed of clan and village chiefs; each tribe had one vote, and unanimity was required for decisions. Under the Great Law of Peace (Gayanesshagowa), the joint jurisdiction of 50 peace chiefs, known as sachems, or hodiyahnehsonh, embraced all civil affairs at the intertribal level.”

b. “The Iroquois Confederacy established that each nation should handle their own affairs. The Great Law of Peace is a unique representational form of government, with the people in the clans having say in what information is passed upward.” (Source: Britannica)

Questions

- What is the Iroquois Confederacy?

- What would the benefits of a confederacy be?

- What is the primary structure of the Great Law of Peace?

- What historical documents remind you of the Great Law of Peace? What documents do you think could have been influenced by the Great Law of Peace?

C. Great Law of Peace

The Great Law of Peace are “teachings [that] emphasized the power of Reason, not force, to assure the three principles of the Great Law: Righteousness, Justice, and Health.” It also includes “instructions on how to treat others, directs them on how to maintain a democratic society, and expresses how Reason must prevail in order to preserve peace.” (Source: Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators)

Selected components:

16. If the conditions which arise at any future time call for an addition to or change of this law, the case shall be carefully considered and if a new beam [law] seems necessary or beneficial, the proposed change shall be voted upon and if adopted it shall be called, “Added to the Rafter.”

24. The chiefs of the League of Five Nations shall be mentors of the people for all time. The thickness of their skins shall be seven spans, which is to say that they shall be proof against anger, offensive action and criticism. Their hearts shall be full of peace and good will and their minds filled with a yearning for the welfare of the people of the league. With endless patience, they shall carry out their duty. Their firmness shall be tempered with a tenderness for their people.

92. If a nation, part of a nation, or more than one nation within the Five Nations should in any way endeavor [try] to destroy the Great Peace by neglect or violating its laws and resolve to dissolve the Confederacy such a nation or such nations shall be deemed guilty of treason and called enemies of the Confederacy and the Great Peace.

93. Whenever a specially important matter or a great emergency is presented before the Confederate Council and the nature of the matter affects the entire body of Five Nations threatening their utter [complete] ruin, then the Lords of the Confederacy must submit the matter to the decision of their people and the decision of the people shall affect the decision of the Confederate Council. This decision shall be a confirmation of the voice of the people.

94. The men of every clan of the Five Nations shall have a Council Fire ever burning in readiness for a council of the clan. When it seems necessary for a council to be held to discuss the welfare of the clans, then the men may gather the fire. This council shall have the same rights as the council of the women.

95. The women of every clan of the Five Nations shall have a Council Fire ever burning in readiness for a council of the clan. When in their opinion it seems necessary for the interest of the people they shall hold a council and their decision and recommendation shall be introduced before the Council of Lords by the War Chief for its consideration. (Source)

Questions

- What do these sections tell you about the values of the Iroquois Confederacy?

- How does the Great Law of Peace differentiate from more modern United States’ government documents?

- What does the Great Law of Peace have in common with the ideals of more modern government?

D. Group Activity: Each group will be working on a separate area of what is now America. The groups are Plains, Northeast, Southwest, and Eastern Woodlands. The groups will look at/research images and readings and answer the sheets that go along with them. They will then participate in a “jigsaw” and fill out the rest of their charts using information from other groups representatives. On each sheet there will be a section at the top where they will write the definitions of nomadic and sedentary, this will be provided by the teacher (see Appendix A).

Plains Indians Information Sheet

“Many people think of the Plains Indians as people who traveled from place to place to find food and basic supplies. Only some of the tribes in this area lived that way. There were more than 30 different tribes who lived in the Great Plains. Like the Europeans who came to America from different countries, these tribes all had their own language, religious beliefs, customs and ways of life.”

“The Plains Indians who did travel constantly to find food hunted large animals such as bison (buffalo), deer and elk. They also gathered wild fruits, vegetables and grains on the prairie. They lived in tipis, and used horses for hunting, fighting and carrying their goods when they moved. Other tribes were farmers, who lived in one place and raised crops. They usually lived in river valleys where the soil was good.”

(Source)

“Most Indigenous societies of the Great Plains practiced some form of hereditary chieftainship and recognized a head chief. In theory, the head chief presided over a council composed of war chiefs, headmen, warriors, and holy men. In practice, however, charismatic, self-made war-party

leaders often exercised the most significant authority, especially in times of crisis.” (Source)

Northeast Indians Information Sheet

The most elaborate and powerful political organization in the Northeast was that of the Iroquois Confederacy. A loose coalition of tribes, it originally comprised the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. Later the Tuscarora joined as well. Indigenous traditions hold that the league was formed as a result of the efforts of the leaders Dekanawida and Hiawatha, probably during the 15th or the 16th century.”

“The Northeast culture area comprises a mosaic of temperate forests, meadows, wetlands, and waterways. The traditional diet consisted of a wide variety of cultivated, hunted, and gathered foods, including corn (maize), beans, squash, deer, fish, waterbirds, leaves, seeds, tubers, berries, roots, nuts, and maple syrup.” (Source)

“Northeastern cultures used two approaches to social organization. One was based on linguistic and cultural affiliation and comprised tribes made up of bands (for predominantly mobile groups) or villages (for more sedentary peoples). The other was based on kinship and included nuclear families, clans, and groups of clans called moieties or phratries.” (Source)

Southwest Indians Information Sheet

“Most peoples of the Southwest engaged in both farming and hunting and gathering; the degree to which a given culture relied upon domesticated or wild foods was primarily a matter of the group’s proximity to water. A number of domesticated resources were more or less ubiquitous throughout the culture area, including corn (maize), beans, squash, cotton, turkeys, and dogs. During the period of Spanish colonization, horses, burros, and sheep were added to the agricultural repertoire, as were new varieties of beans, plus wheat, melons, apricots, [and] peaches.” (Source)

“For those groups that raised crops, the male line was somewhat privileged as fields were commonly passed from father to son. Most couples chose to reside near the husband’s family (patrilocality), and clan membership was patrilineal. In general women were responsible for most domestic tasks, such as food preparation and child-rearing, while male tasks included the clearing of fields and hunting.” (Source)

“Among the Navajo the preferred house form was the hogan, a circular lodge made of logs or stone and covered with a roof of earth; some hogans also had earth-berm walls. Among the Apache, the wickiup and tepee were used.” (Source)

Upland settlements “included dome-shaped houses with walls and roofs of wattle-and-daub or thatch. The groups that relied on ephemeral streams divided their time between summer settlements near their crops and dry-season camps at higher elevations where fresh water and game were more readily available. Summer residences were usually dome-shaped and built of thatch, while lean-tos and windbreaks served as shelter during the rest of the year.” (Source)

Southern Woodlands “Indians” Information Sheet

“The importance of corn in the Southeast cannot be overemphasized. It provided a high yield of nutritious food with a minimal expenditure of labour; further, corn, beans, and squash were easily dried and stored for later consumption. This reliable food base freed people for lengthy hunting, trading, and war expeditions. It also enabled a complex civil-religious hierarchy in which political, priestly, and sometimes hereditary offices and privileges coincided.” (Source)

“Most of the region teemed with wild game: deer, black bears, a forest-dwelling subspecies of bison, elks, beavers, squirrels, rabbits, otters, and raccoons. In Florida, turtles and alligators played an important part in subsistence. Wild turkeys were the principal fowl taken, but partridges, quail, and seasonal flights of pigeons, ducks, and geese also contributed to the diet. The feathers of eagles, hawks, swans, and cranes were highly valued for ornamentation, and in some tribes a special status was reserved for an eagle hunter.” (Source)

“In general, settlements were semi-permanent and located near rich alluvial soil or, in the lower Mississippi region, near natural levees. Such land was easily tilled, possessed adequate drainage, and enjoyed renewable productivity.” (Source)

“In much of the region, people built circular, conical-roofed winter “hot houses” that were sealed tight except for an entryway and smoke hole. Summer dwellings tended to be rectangular, gabled, thatch-roofed structures made from a framework of upright poles.” (Source)

LESSON 3. How did Native Americans, like the Mi’kmaq, interact with foreign societies, like the Norse?

The Norse arrived North America, but their settlements disappeared. Evidence suggests that Norse Viking, Leif Eriksson, traveled to North America in 1000 A.D, roughly 500 years before other European explorers. Students investigate how, why, and where the Norse settled in North America. Students interpret the interactions between the Norse and the Mi’kmaq. It is believed that the Norse voyage to the new continent was the result of climatic fluctuations that forced settlers to seek new lands in an effort to survive and prosper. Upon their arrival to Newfoundland, evidence from the Greenlander Saga suggests that Norse Vikings encountered the Native American tribe, The Mi’kmaq, periodically engaging in limited trade with them, before the two groups engaged in conflict leading some researchers to speculate this was a cause of their disappearance. Students will examine how the physical environment and natural resources of North America influenced the development of the first human settlements and the culture of Native Americans as well as impacted on early European settlements. Students will research and write a 250-word argumentative short-essay, in which they introduce factors they believe influenced the disappearance of the Norse Vikings. Enduring issues and unifying themes include Impact of the Environment, Trade, Technology, and Conflict on human societies.

CONTENT VOCABULARY:

- Norse– Settlers, traders, farmers, and seafarers who originated in Scandinavia.

- Viking – Norse warriors and seafarers.

- Vinland– An area of coastal North America explored by Vikings.

- L’Anse aux Meadows – Remains of an 11th-century Viking settlement in Newfoundland

- Mi’kmaq- Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada’s Atlantic Provinces.

- The Viking Compass

Vikings did not have much material to work with other than wood and animal hair, to make it across the oceans, but they apparently didn’t require much more than that to get to where they were going and make it back again. In 1948 a (partial) wooden artifact was found in Greenland (called the Uunartoq disk), which was assumed to be some form of compass. Only representing a portion of a wheel or ‘disk,’ the partial device had notches carved around the perimeter and scratch marks at a few distinct intervals across the face. (Source)

- Questions:

- According to the text, what was needed, in order to use the “Viking Compass”?

- Why is a compass important when traveling long distances across the ocean?

- How might the discovery of this artifact change how we understand European Exploration of the Americas?

- Evidence that the Norse reached North America

According to the “Saga of the Greenlanders”, Vikings became the first European to sight mainland North America when a Viking merchant, headed for Greenland, was blown westward off course about 985. Further, about 1000, Leif Eriksson, a notorious viking leader, is reported to have led an expedition in search of the land sighted by the viking merchant, and found an icy barren land he called Helluland (“Land of Flat Rocks”) before eventually traveling south and finding Vinland (“Land of Wine”).The narratives of exploration of a place that sounded like Maine, Rhode Island, or Atlantic Canada were thought to be just stories, until 1960, when Helge Ingstad, a Norwegian explorer, and archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad, were led by a local man to a site on the northern tip of Newfoundland island. At L’Anse aux Meadows, they discovered the remains of a Viking encampment that they were able to date to the year 1000 — That’s almost 500 years before the Europeans landed in the Americas! (Source)

Questions

- Who led the Viking expedition to North America?

- How long before Columbus, did the Vikings arrive in North America?

- Do you think that it is fair to say that the Vikings discovered North America? Explain.

C. The Norse meet the Mi’kmaq

The Mi’kmaq are among the original inhabitants of the Atlantic region in Canada, and inhabited the coastal areas of Gaspé and the Maritime Provinces east of the Saint John River. This traditional territory is known as Mi’gma’gi (Mi’kma’ki) and is made up of seven districts. Mi’kmaq people have occupied their traditional territory, Mi’gma’gi, centuries before the arrival of the Vikings. Today, the remaining members of the Mi’kmaq community continue to occupy this area, as well as settlements in Newfoundland and New England, especially Boston. While it is not entirely clear, as to how the Mi’kmaq and the Vikings interacted, historical accounts of their interactions have suggested that the Mi’kmaq not only engaged in trade with the Vikings, but they also found themselves engaged in conflict with one another as well.

Going further, researchers have since discovered that the Mi’kmaq had developed oral histories that speak of a Mi’kmaq woman’s ancient premonition [dream] that people would arrive in Mi’gma’gi on floating islands, and a legendary spirit who traveled across the ocean to find “blue-eyed people.” Since the story’s discovery, many individuals have regarded its existence as a foretelling of the arrival of Europeans.

Questions:

- What areas of the present-day United States and Canada did the Mi’kmaq people inhabit?

- How might the “ancient premonition” [ancient dream] of “blue-eyed people” arriving in North America help us understand how Native Americans viewed and interacted with European explorers?

D. Unknown American Holiday: Leif Erikson Day

Leif Erikson was likely born in Iceland around 970 or 980 AD, and was the son of infamous Norse chieftain, Erik the Red. Leif, much like his father, was a true Viking from the start, and began sailing with his crew across present-day western Europe and parts of Scandinavia. Nevertheless, the story begins with Leif traveling to present-day Greenland. It was on this journey in approximately 999 AD, that Leif Erikson and his crew would be blown off-course, to a location they named “Vinland,” meaning “Land of

Wine.” While at first it would appear that Erikson found something other than North America, the descriptions of the surrounding area and its inhabitants have led researchers to believe that Erikson is writing about his arrival in North America. In 2024, President Joseph Biden declared October 9th Leif Erikson Day. (Source)

Questions:

- When did Leif Erikson arrive in North America?

- In your opinion, why does Leif Erikson Day have less recognition than Columbus Day?

E. Group Activity—Investigate the Disappearance the Newfoundland Norse Settlement

Instructions: In groups of three or four, students will be tasked with investigating the possible reasons for the Norse Vikings’ mysterious disappearance from their North American settlement.

Station #1: Climate Change

| There was a time centuries ago that settlements in cold northern lands grew little by little with the arrival of new inhabitants. Up to the 15th Century, the territories we now know as Greenland and Newfoundland in North America, reached population sizes of around 2,000. From then on, these lands began to depopulate. Early research said the exodus was due to many problems, but temperature change has often been cited as an explanation for the end of the Vikings. According to this theory, the Nordics arrived in the North during a period that was more or less warm, where they could survive until temperatures fell during a period known as, the Little Ice Age. | |

Now, new research by the College of Natural Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst concludes that summers were increasingly warm and dry in Greenland and Newfoundland during the time the Nordic settlements were abandoned. Thus, the trigger for the disappearance of the Vikings could have been drought. Source:Climate history: Why did the Vikings disappear from northern lands?].

Questions

1. What other regions did the Vikings visit?

2. How did climate impact the survival of the Vikings in North America?

3. What climate event occurred that made it more difficult for Vikings to live in North America?

Station #2: Conflict with the Native Americans

[Source:When Vikings Clashed with Native North Americans ].

The settlement at L”Anse aux Meadows was only in use for roughly twenty years or so. It’s estimated that the Vinland settlements lasted the same amount of time.While scholars do not know why the Vikings abandoned the settlements so quickly, there are several theories. Hostile relations with the natives surely did not help matters. Though their iron tools aided them in battle, the natives dramatically outnumbered the Vikings who only numbered at most in the low hundreds. In an early encounter, one of the viking chieftains that lead the group of norse settlers in Newfoundland, Leif Eiriksson, is recorded to have been “struck by an arrow”. It would later be determined through these records —The Vinland Sagas—that his injuries would prove fatal. While it is not clear what tribes attacked the Vikings during their stay, evidence suggests that it was likely a number of Inuit tribes, including the Mi’kmaq. That being said, due to the increased amount of conflict between the Vikings and Native tribes, the Vikings dubbed their enemies Skraelings, which historians believe translates as either “barbarian” or “foreigner” in the old Norse tongue. It could have also meant “weak” or “sickly” or even “false friend”.

Questions

- According to the document, how long were the Vikings in North America?

- How did conflict with the Native Americans impact the Vikings living in North America?

- Why do you think the Vikings were attacked by Native Americans?

Station #3: Economics

[Source: Why didn’t the Vikings colonize North America? | Live Science : ].

When the Vikings explored south of Newfoundland, in an area they named “Vínland” (which translates as “Wine Land”), they were more interested in finding natural resources they could exploit. However, Kevin P. Smith, a research associate at the Smithsonian Institute who specializes in the Vikings, had a somewhat different opinion. He said that Norse texts indicate that some Vikings believed it offered “opportunities for ‘second sons’ of the chieftain who had established the Greenland colony to carve out their own areas where they could be leaders/chiefs rather than second sons.

Be that as it may, there is a leading theory that presumes the Vikings had abandoned the settlement largely due to its decline in economic importance. For instance, Medieval Europe had coveted [desired] walrus ivory leading to the market’s expansion across the North Atlantic. As such, and by the time the Vikings had sailed to and settled in North America, a series of large walrus colonies had already been established in Northern Greenland, which researchers speculate, ultimately diminished the economic significance of the North American settlement. Going further, many researchers have also speculated that the abandonment of the settlement was also influenced by the nature of walrus tusk hunting; It was dangerous, time consuming, and expensive.

Questions

- Using the text, define the term “Vinland.”

- Why was the settlement in North America important for the Vikings?

- What economic factors influenced the Vikings to abandon their settlement in North America? Explain.

Station #4: Distance

[Source: The Norse in the North Atlantic ].

Another important question is why the Norse failed to settle permanently in North America. How was it that they could survive in Greenland for 500 years, but could not establish themselves in Vinland, with its richer resources and better climate? Vinland was a remote place, and voyaging there was risky and uncertain, as we know from the sagas. In the early 11th century, the Greenland settlements were still young and did not have the population nor the wealth to support a new colony in North America. Additionally, there was also little incentive, in that the economy which developed in Greenland did not need expansion to America. There might have been some incentive later in the history of the Greenland settlements, but by that time — the13th and 14th centuries — the inhabitants were preoccupied with their own survival and would not have had the resources or the interest to create a new colony. Greenland was a fragile colony, incapable of sustaining itself as climatic, economic, and political conditions deteriorated. According to Thomas McGovern, a leading authority on Norse expansion to North America, “Greenland simply did not produce enough people or riches to act as a successful base for sustained colonization attempts, and Norse Greenlanders may have seen little immediate benefit in expanding in Vinland.”

Questions

- How did the Norse colony at Greenland impact the settlement in North America?

- Why did the Norse colony in Greenland begin to collapse?

- What happened during the 13th and 14th centuries that prevented Vikings from settling in North America?

LESSON 4. How did interactions among Native Americans and outsiders challenge our understanding of early exploration and the “discovery” of America? It is still debated how and when early humans arrived in North America. Eventually a number of Native American tribes existed across the modern-day United States and the Americas. The laws and alliances, like the Iroquois Confederacy and the Great Law of Peace, made by Native Americans between themselves and outsiders may have contributed to the founding documents of the United States. This lesson is a Socratic Seminar. Students will have collaborative discussions, work civilly and democratically to evaluate diverse perspectives about how early humans migrated to the Americas, the significance of the Great Law of Peace on American law, and the dangers of leaving groups of people out when learning about history. Enduring Issues will be discussed in this lesson include Power and the Impact of Immigration.

VOCABULARY REVIEW MATCHING ACTIVITY

| The Bering Land Bridge Clovis First Theory Solutrean Hypothesis Trans-Pacific Migration Theory The Great Law of Peace Artifact Migration Clovis People Nomadic Sedentary Confederacy Iroquois Confederacy Saga of the Greenlanders Mi’kmaq Plains tribes Northeastern tribes Southwestern tribes Southern Woodlands tribes | A. An ancient culture of North America that lived between 10,000 and 9,000 BCE B. The first humans to reach the Americas migrated from Asia by traveling across the Pacific Ocean C. Nomadic people who resided largely in the western plains D. Source on Norse colonization of North America E. Group of people joined together for a common purpose F. The practice of living in one place for a long time G. People who move from one place in order to settle in another H. Indigenous people of what is now Canada and Nova Scotia I. Art, tools, and clothing made by people of any time and place J. Sedentary people of Alaska and Northwestern California K. Sedentary people who resided largely near the Atlantic Ocean L. Oral constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy M. Communities who move from one place to another N. Confederation governed by the Great Law of Peace O. Land bridge connecting Asia to North America P. Hunters considered the first people to arrive in the Americas Q. Belief that early Europeans arrived in the Americas R. People who resided in present day New Mexico and Arizona |

COMPELLING QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION:

- Who should be called the “first Americans?” Should anyone?

- What could be the consequences of designating one group of people as the “first” be?

- Why would it be important to recognize all of the different groups you learned about? What could happen if we do not mention them?

- What is the danger of forgetting or leaving out groups of people from history? Is there any?

- Which theory of migration do you think is most plausible?

- Why do people migrate? Have the motives for migration changed from then to now? How so?

- How do we make welcoming communities for those who migrate?

- How has your understanding of Indigenous American history and the “discovery” of America changed?

- How did interactions among Native Americans and outsiders challenge our understanding of early exploration and the “discovery” of America?

Appendix A: Sample Worksheet

| Nomadic or Sedentary | Housing | Leadership Structure | Location (Modern Country and State) | Tribes | Food Sources | |

| Plains | ||||||

| Northwest | ||||||

| Southwest | ||||||

| Eastern Woodlands |