Bartolomé de Las Casas: Defender of the Indians

Dan La Botz

Reprinted with permission from NewPolitics.

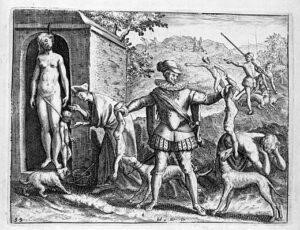

Figure 1: Theodore de Bry’s illustrations to Las Casas’ Brief Account of the Conquest of the Indies.

Bartolomé de las Casas was born in 1484 in Seville, to a French immigrant merchant family that had helped to found the city. One biographer believes his family were conversos, that is, Jews who had converted to Catholicism. As a child, in 1493 he happened to witness Christopher Columbus’ return from his first voyage to the Americas to Seville with seven Indians and parrots that were put on display. Queen Isabella ordered the Indians to be returned to their native land.

Bartolomé’s father, Pedro de las Casas, joined Columbus on his second voyage and brought home to Seville as a present for his son Bartolomé an Indian. In 1502 Pedro took Bartolomé with him on the expedition of Nicolás de Ovando to conquer and colonize Española (in English the island of Hispaniola, today made up of the Dominican Republic and Haiti). Bartolomé conducted slave raids on the Taino people (who were virtually annihilated by the Spaniards) and was rewarded with land and became the owner of a hacienda as well as slaves. In 1506 he returned to the University of Salamanca, where he had previously studied, and then traveled to Rome where he was ordained, becoming a priest in 1507.

When in 1510 Dominican friars led by Pedro de Córdoba arrived in Santo Domingo, they were horrified at the Spaniards’ treatment of the Indians, the massacres, the brutality of slavery, and the intense exploitation of the natives and they denounced it. Las Casas rejected the Dominicans’ criticism and defended the encomienda system by which Spaniards distributed laborers to the conquerors.

In 1513, Las Casas joined the expeditions of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar and Pánfilo de Narváez to conquer Cuba, acting as chaplain. He witnessed horrifying murders and torturers of the indigenous people. Once again, he received a reward, this time of gold and slaves. For a year he lived as both colonist and priest. Then in 1514, while studying the Book of Ecclesiasticus, he came across a passage that called his beliefs into question. It read:

If one sacrifices from what has been wrongfully obtained, the offering is blemished; the gifts of the lawless are not acceptable. … Like one who kills a son before his father’s eyes is the man who offers sacrifice from the property of the poor. The bread of the needy is the life of the poor; whoever deprives them of it is a man of blood.

Reading this passage — and no doubt meditating on the horrors that he had both participated in and witnessed — Las Casas suddenly decided to break with his past. He gave up his haciendas, his encomienda, his slaves. He began to encourage others Spaniards to do the same, but of course they refused and they resented him.,Las Casas then traveled to Spain to take his case to King Ferdinand, and he succeeded in having one meeting with him, but then the monarch died in 1516. Many of the other higher-ups in the Spanish state and Church, such the Bishop of Burgos, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, who controlled the Crown’s business in the Americas, were themselves encomenderos who profited from the labor of the indigenous and they rejected Las Casas’ appeals to protect the Indians. Fearing that the entire population of the Indies, the Caribbean islands, might be annihilated, Las Casas wrote his Memorial de Remedios para las Indias (Memorandum on Remedies for the Indies) to be presented to the regents who now rules, calling for a moratorium on all Indian labor to protect the indigenous people and allow the recuperation of their populations.

Convinced by Las Casas’ argument that the Indians needed to be protected, one of the regents, Cardinal Ximenes Cisneros, put the Carmelite monks in charge of the Indies. Las Cases himself was given the official title and position of “Protector of the Indians. Under pressure from Las Casas, in 1542 King Charles V promulgated the New Laws to protect the Indians from exploitation.

King Carlos V, concerned about conditions in the Spanish American colonies decided to organize a debate between the two principal intellectuals on opposite sides of the question. Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, claimed that the indigenous people of the Americas were barbarians: ignorant, unlettered, and unreasoning, incapable of learning anything except the simplest tasks. The Spaniards, he argued, being superior in intelligence and morality, had the right to make war on them and conquer them. The Indians were, he said, incapable of governing themselves. He argued that they were sunk in depravity, worshiping idols and engaging in human sacrifice. He quoted the Bible and other authorities to argue that in ancient times such people had been justly exterminated or enslaved. Natural law, he averred, dictated that the Spaniards, superior in intelligence and morality, should govern them.

In response, Las Casas either refuted Sepúlveda’s arguments, such as the claim that the indigenous Americans were ignorant and incapable of governing themselves, by providing evidence of their intelligence and self-government, or he argued, as in the case of idolatry and human sacrifice, that these practices had to be seen as demonstrating their religious inclination, their attempts to worship God. Las Casas denied the Spaniards’ right to ever invade, occupy, conquer, and subject the indigenous. He argued that the Spaniards’ wars against the Indians were unjust and therefore enslavement of the Indians was illegal and wrong, since only the captives of a just war could be enslaved.

| De Las Casas and Sepúlveda Debate Treatment of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas |

Theologian Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda

“The servitude contracted in a just war is legal, and the booty acquired becomes the rightful possession of the victor. But concerning these barbarians, the plight of the Indians defeated by Spanish arms in formally declared war is very different from the circumstances of those who, through prudence or fear, delivered themselves to the authority of the Christians. Just as in the former case the victorious prince may determine, according to his will and right and bearing the public good in mind, the fate of the vanquished, in the latter both civil laws and jus gentium (international law) would rule unjust to deprive the natives of their goods and to reduce them to slavery; it is, however, licit to keep them as stipendiaries and tributaries as befitting their nature and condition.” “The nature of their governance over the barbarians must be such that the latter will not be given, through the granting of a degree of freedom unwarranted by their nature and condition, the opportunity to return to their primitive and evil ways; on the other hand, they must not be oppressed with harsh rule and servile treatment, for, tired of servitude and indignity, they may attempt to break the yoke to the peril of the Spaniards.”

Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas

| “Among our Indians of the western and southern shores (granting that we call them barbarians and that they are barbarians) there are important kingdoms, large numbers of people who live settled lives in a society, great cities, kings, judges, laws, persons who engage in commerce, buying, selling, lending, and the other contracts of the law of nations . . . Reverend Doctor Sepúlveda has spoken wrongly and viciously against peoples like these, either out of malice or ignorance . . . and therefore, has falsely and perhaps irreparably slandered them before the entire world? From the fact that the Indians are barbarians it does not necessarily follow that they are incapable of government and have to be ruled by others, except to be taught about the Catholic faith and to be admitted to the sacraments. They are not ignorant, inhuman, or bestial. Rather, long before they heard the word Spaniard they had properly organized states, wisely ordered by excellent laws, religion and custom . . . Since, therefore, every nation by the eternal law has a ruler or prince, it is wrong for one nation to attack another under pretext of being superior in wisdom or to overthrow other kingdoms. For it acts contrary to the eternal law, as we read in Proverbs . . . ‘This is not an act of wisdom, but of great injustice and a lying excuse for plundering others.” |

Questions:

- What term does Sepúlveda use to describe the indigenous people of the Americas?

- According to Sepúlveda, when are slavery and “booty” justified?

- What does Sepúlveda recommend for governance in the Americas?

- What evidence does De Las Casas offer to refute claims made by Sepúlveda?

- If you were in the audience during this debate, what questions would you ask them?

- Whose position do you agree with more? Why?