History of European Antisemitism

Institute for Curriculum Resources

This lesson plan on the History of European Antisemitism is a critical tool for social studies teachers, empowering students with the context and critical skills to analyze the evolution of deep-seated hatred. The lesson is indispensable for World History by demonstrating how the Holocaust was the result of centuries of cumulative antisemitism. Furthermore, it strengthens U.S. History curricula by providing the historical framework needed to study WWII and genocide.

Essential Questions

- What is antisemitism?

- What are four historical forms of antisemitism?

- How have these four forms of antisemitism been expressed throughout history?

- How can these four forms of antisemitism be expressed in modern times?

- What does modern antisemitism, or anti-Jew hate look like?

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to:

- Define antisemitism.

- Identify four forms of antisemitism (religious, economic, political, and racial) which are interconnected and have manifested in various ways over time.

- Trace the evolution of antisemitism from pre-Christian to modern times.

- Understand that anti-Jew hate evolves and manifests in ways that don’t fit into the historical forms.

Materials Needed

PRIMARY SOURCES

This slide deck contains the nine primary source examples below. The speaker notes on each slide explain the type of historical form of antisemitism the source represents, as well as offer guides for analysis of each source. Additional context and suggested use for them can be found in the lesson plan, beginning at Section 4.

- SOURCE 1: Ecclesia And Synagoga, 1300 CE

- SOURCE 2: (optional) Excerpt from Law of Theodosius II, 438 CE

- SOURCE 3: German depiction of Blood Libel and Judensau, 15th century

- SOURCE 4: (optional) Excerpt from Solomon bar Simson Chronicle, 1140

- SOURCE 5 Excerpt from Henry Ford’s The International Jew, 1920

- SOURCE 6: Political cartoon “Metamorphosis” from Simplicissmus, 1903

- SOURCE 7: Excerpt from a letter written by Hitler to Adolf Geimlich, 1919

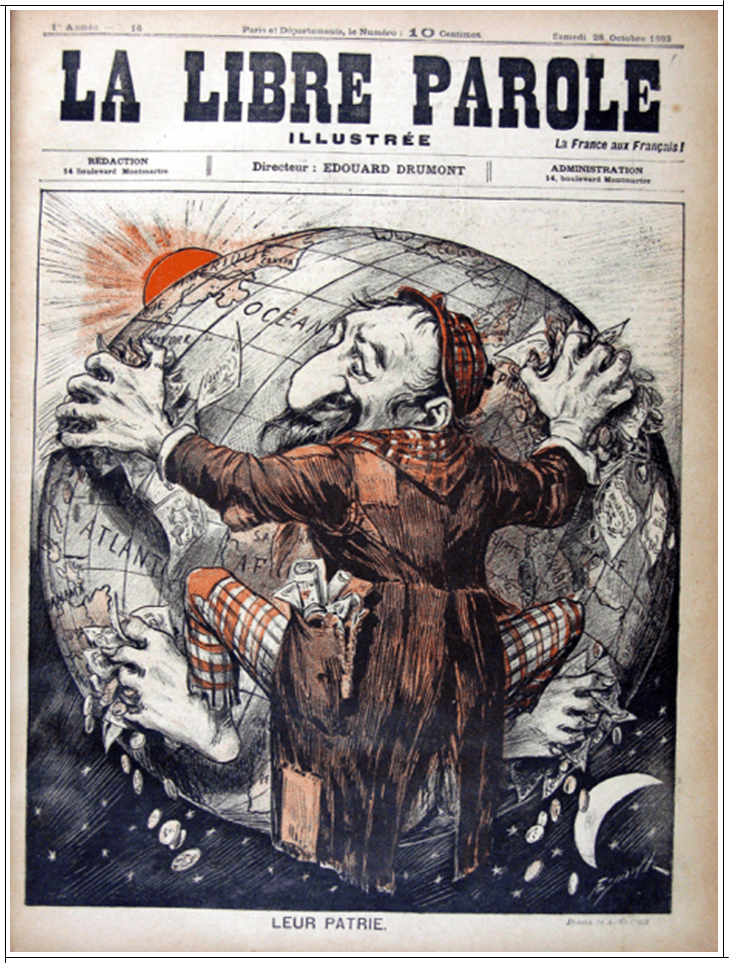

- SOURCE 8: Magazine cover of the French publication “La Libre Parole,” 1893

- SOURCE 9: Excerpt from speech by Senator Ellison DuRant Smith of South Carolina in support of the 1924 Federal Immigration Act

RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS

- Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation: The History of European Antisemitism

- Antisemitism Glossary of Terms (PDF)

- Modern Antisemitism Gallery Walk: instructions, sources, questions, student note-catcher (PDF)

- Digital Version of the Modern Antisemitism Gallery Walk

- Primary Sources Only Deck: Historical Antisemitism (View Only)

- Understanding Zionism, Anti-Zionism, and Antisemitism (PDF)

HANDOUTS

OPTIONAL ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES ON ICS WEBSITE

Note on Lesson Content

- This lesson contains information, images, and text that reveal the extensive discrimination that Jews have faced historically and continue to face in the modern world.

- This information can be difficult; allow time to reflect and process.

- The term “anti-Jew hate” is a synonym for antisemitism, and both terms are used throughout the lesson. Simply put, antisemitism is anti-Jew hate.

- Education about history is key to learning from society’s past injustices and creating a more equitable society. By educating students about anti-Jew hate, we can help them understand the harmful effects of prejudice and encourage them to work towards creating a more tolerant and inclusive society. Here are some specific reasons why we should teach students about antisemitism:

- To raise awareness: Many students may not know what antisemitism is or how it manifests in our society. By teaching them about anti-Jew hate, teachers can help raise awareness and encourage students to recognize and challenge instances of antisemitism when they encounter them.To encourage critical thinking: Learning about antisemitism can help students develop critical thinking skills. They can analyze the historical and cultural contexts that have contributed to anti-Jew hate and evaluate the different and evolving ways that it manifests in our society.To promote empathy: Learning about anti-Jew hate can help students develop empathy for those who have experienced discrimination and prejudice. This can help students better understand the experiences of others and become more compassionate and tolerant individuals.

- To prevent hate crimes: Antisemitism is a form of hate that can lead to violence and discrimination. By teaching students about it, teachers and students can help prevent hate crimes and create a safer and more inclusive community.

Lesson Plan

1. INTRODUCTION

It’s important to learn about the wider context – the various historical events – which have influenced the evolution of antisemitism.

The following points may be helpful as you introduce the topic:

- Today, we will be learning about the history of European antisemitism, including its origins in the ancient Mediterranean world, its evolution through European history, and its manifestations in modern culture. Many people think that antisemitism started with Hitler and the Nazis. However, antisemitism goes back to ancient times.

- Unfortunately, antisemitism continues today – both abroad and in the United States. In fact, there are sometimes incidents of antisemitism in countries with very few or no Jews.

- Antisemitism is complex and has a number of forms. Antisemitism cannot be properly understood without understanding its religious roots, which is where this lesson begins.

Understanding lesson structure: The following content of the lesson plan is directly mirrored in the presentation deck, which is available on the website. As you are reviewing this lesson plan, please make sure you are referring to the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation to familiarize yourself with the full content and its presentation.

2. DEFINING THE TERM “ANTISEMITISM”

Before diving into the history of antisemitism, it’s important to first define the term and ensure that everyone has a clear understanding of what it means. You can begin by asking your students how they would define antisemitism. Then, ask them to consider their answers in light of the definition of antisemitism outlined below. You will find a slide with the definition in the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation as well as the Antisemitism Glossary of Terms (PDF).

Definitions for antisemitism vary, but ultimately, they all come down to the same thing: Antisemitism is hatred, discrimination, fear, and prejudice against Jews based on stereotypes and myths that target their ethnicity, culture, religion, traditions, right to self-determination, or connection to the State of Israel.

The term Jew-hate can be used interchangeably with the word antisemitism, as they both mean the same thing.

To best communicate that antisemitism is a word for anti-Jew hate, ICS, along with the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Associated Press, and the New York Times all use the single-word spelling.

3. ASSESS PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

Before jumping into the history of antisemitism, begin with what students may already know about this particular type of hatred. Choose one of the following activities to introduce the topic:

- Option 1: Using the Prior Knowledge Handout, assess prior knowledge and particular areas of interest among students.

- Option 2: More informally, have a brief class discussion around the topic. Some possible questions for starting the conversation can include the following questions. You may want to consider allowing your students time to process these questions in writing first, so that they feel more prepared to share their thoughts.

- How long do you think anti-Jew hate has been around?

- Where have you learned about antisemitism or past antisemitic events?

- Why do you think it is important to learn about antisemitism?

- What does it mean for a group of people to feel “othered”?

- What do you know about how anti-Jew hate looks today?

Next, explain to your students that you’ll be exploring the history of this hatred. As you go through the presentation, students will see how and why the various stereotypes and myths developed. Understanding this history will also help students to identify antisemitism in their own world, especially as they see the modern examples in the closing activity.

Note:As you go through the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation, you can have your students take notes using the graphic organizers. There are two versions of the organizer – one that has specific prompts to help students look out for key information, and the other is open-ended and allows students to jot down whatever notes they feel are most important.

4. ANTISEMITISM’S ANCIENT ROOTS

Guiding Questions: Why were Jews seen as “other” in the Ancient world? What external factors contributed to furthering Jews’ status as “other”?

Share an overview of antisemitism’s ancient roots. The notes below, as well as additional content, are presented through correlating slides in the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation. Please refer to the Antisemitism Glossary of Terms for additional definitions of the bolded words below.

- Judaism originated in the Land of Israel around the 12th century BCE.

- Judaism’s notion of monotheism was seen as a radical departure from the polytheistic beliefs that were prevalent in ancient times. This difference in belief, as well as distinct religious practices, often set Jews apart, leading them to be viewed as “other” in the societies in which they lived.

- The destruction of the Second Jewish Temple and the creation of the Jewish Diaspora in 70 CE furthered the“othering” of Jews. Jews became viewed as outsiders, with their safety and well-being dependent on the tolerance of others.

- Meanwhile, upon the Roman crucifixion of Jesus in 30 CE, Christianity began to spread. One of the ways that Christianity distinguished itself from Judaism was through the concept of replacement theology.

- In 380 CE, Christianity became the official religion of Rome. In 438 CE, the Roman Empire codified anti-Jewish laws through the Theodosian Code, which established Christianity’s legal dominance over Judaism.

- Even after the Roman empire dissolved in the 5th century, succeeding kingdoms and monarchs continued to use the anti-Jewish legal codes of the Roman Empire.

Share SOURCE 1: Ecclesia and Synagoga[1]

Context:

Tell students that this pair of figures personifies the Christian Church (Ecclesia) and Judaism (Synagoga). In the medieval period, they often appeared sculpted as large figures on either side of a church or cathedral entry, and still exist at some places like Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Use the “see-think-wonder” structure to have students analyze what these sculptures are communicating. Facilitation instructions for this primary source analysis discussion are included in the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation.

Primary Source:

Step 1: SEE – What do you notice about the figures? Possible responses:

Ecclesia

- Young, attractive, adorned with a crown

- Holding a chalice and cross-topped staff

- Looking confidently forward

Synagoga

- Blindfolded and drooping/hunched over a bit

- Carrying a broken lance (possibly an allusion to the Holy Lance that stabbed Jesus) and the tablets of Jewish Law that may be slipping from her hand

Step 2: THINK – What do these details suggest? What message do you think these details communicate?

- Elicit student ideas and guide students in their thinking to understand that this is a visual representation of replacement theology. Judaism is being portrayed as an obsolete or flawed religion that is “blind” to the “true” revelation of Christianity.

Step 3: WONDER – What questions do you have?

- Students may wonder about the objects in their hands, or they may wonder about the difference in dress. These are great opportunities for further student inquiry.

Optional: Share SOURCE 2: Excerpt from Law of Theodosius II

Context:

The Theodosian Code, which codified anti-Jewish laws, was adopted in 438 CE, roughly 60 years after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. The following excerpt reveals some of its concrete prohibitions against Jews, as well as some of the attitudes that formed their basis.

Primary Source:

“Wherefore, although according to an old saying ‘no cure is to be applied in desperate sicknesses,’ nevertheless, in order that these dangerous sects which are unmindful of our times may not spread into life the more freely, in indiscriminate disorder as it were, we ordain by this law to be valid for all time: No Jew – or no Samaritan who subscribes to neither religion – shall obtain offices and dignities… Indeed, we believe it sinful that the enemies of the heavenly majesty and of the Roman laws should become the executors of our laws – the administration of which they have slyly obtained… should have the power to judge or decide as they wish against Christians…, and thus, as it were, insult our faith.” [2]

First, consider guiding a discussion allowing students to again share what they see – what stands out to them from this quote. Then, ask students to more specifically identify:

- How are Jews being described/perceived by Roman law?

- sly/untrustworthy

- dangerous

- Where do you see elements of a Christian theological view?

- Jews being described as “enemies of the heavenly majesty,” and “insult to our faith”

- What are Jews prohibited from doing?

- serving in public office, presiding in courts → in other words, having any kind of authority over Christians

Explain to students that the ancient origins of antisemitism laid the groundwork for the emergence and persistence of various forms of antisemitism throughout history. In the remainder of this lesson, we will explore four forms of antisemitism – religious, economic, political, and racial – and how they were expressed in the past. It’s important to note that, even though some forms developed earlier than others, there is often overlap or a combination of multiple forms.

5. HISTORICAL FORM OF ANTISEMITISM: RELIGIOUS

Guiding Questions: How did Christianity depict Jews as a threat? What are some historical examples of religious antisemitism?

The notes below, as well as additional content, are presented through correlating slides in the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation. Please refer to the Antisemitism Glossary of Terms for additional definitions of the bolded words below.

● By the early medieval period, Christianity had emerged as the dominant force in both daily and political European life. This power structure reinforced the belief that Christians were superior to Jews. Depicting Jews as a threat to the social order became central to European culture, as the following examples illustrate:

- Jews were accused of deicide

- The deicide charge was used to justify the murder and forced conversion of Jews during the Crusades (1096-1272)

- Jews were seen as a threat to Christian purity

- Jews were forced to wear identifying markers (such as yellow badges or special hats) to ensure that a Christian would not accidentally marry a Jew (1215)

- Jews were forced to live in segregated areas known as ghettos and were excluded from all activities in mainstream society (13th century)

- Jews were associated with the devil and evil

- Jews were commonly depicted as having devilish features (e.g., horns, forked tail); Judensau (pronounced you-den-saw) became a category of art portraying Jews engaging in derogatory interactions with pigs

- Jewish customs were seen as nefarious, for example, Christians claimed Jews used the blood of Christian children in baking matzah for Passover

- The blood libel accusation resulted in the blame and killing of Jews when a Christian child would go missing

Share SOURCE 3: German depiction of Blood Libel and Judensau.

Context:

The artwork below from Medieval Germany displays several of the elements of religious antisemitism described above, including blood libel, Judensau, associations with the devil and evil, and Jews being forced to mark their identity through their clothing. Ask students to carefully examine the visual and describe the connections they make to religious antisemitism.

*Important Teacher Note – Content Warning: Please note that the visual content in this source contains more mature elements. Please consider if this is appropriate for the age group and setting in which you teach. Consider using the alternate image provided below.

Primary Source [3]:

Questions for students: How are Jews being depicted in the image? What harmful myth about Jews is represented? How does an image like this reinforce religious antisemitic views?

Possible Responses:

- On top is an image of Simon of Trent, reinforcing the blood libel myth

- Below, Jews are depicted as being engaged in disgusting and lewd actions with a pig (considered an unclean animal in Jewish tradition) – this represents the idea of Judensau:

- A Jewish man is placing his mouth on a pig’s anus

- A Jewish child is suckling from the pig

- A Jewish man is riding backwards on the pig, alluding to his “backwards” nature in his rejection of Christianity

- Both the Jews and the devil are wearing circular badges (one of the identifying markers that Jews were forced to wear in parts of Europe)

Alternate image option: [4]

Optional: Share SOURCE 4: Excerpt from Solomon bar Simson Chronicle[5].

Context:

By the 11th century, as a result of becoming a diaspora, Jews had settled across many regions of Europe and the Middle East. In 1096, Pope Urban II launched the First Crusade to regain the Holy Land from Muslim rule. Unfortunately, a number of Jewish communities lay en route to the Eastern Mediterranean and were attacked by the Crusaders. Many Christians viewed Jews negatively because they did not embrace Jesus. So, although the Crusaders set off to fight “enemy Muslims,” they quickly incorporated attacking “enemy Jews” as part of their mission. As the Crusaders made their way through France and Germany, they burned synagogues, forced conversions, brutally massacred Jews, and incited anti-Jewish riots.

The following excerpt is from a source known as the “Solomon bar Simson Chronicle.” The chronicle is a Jewish account of the First Crusade.

Primary Source:

“Now it came to pass that as they [the Crusaders] passed through the towns where Jews dwelled, they said to one another: “Look now, we are going a long way to seek out the profane shrine [Jerusalem] and to avenge ourselves on the Ishmaelites [Muslims], when here, in our very midst, are the Jews—they whose forefathers murdered and crucified him [Jesus] for no reason.” Let us first avenge ourselves on them and exterminate them from among the nations so that the name of Israel will no longer be remembered, or let them adopt our faith and acknowledge the offspring of promiscuity.”

First, consider guiding a discussion, allowing students to again share what they see – what stands out to them from this quote? Then, ask students to specifically discuss:

- According to this quote, what did the Crusaders want to do to the Jews?

- Kill them all (“exterminate them from among the nations”)

- What religious antisemitic notions did the Crusaders use to justify their actions?

- Deicide charge (“those whose forefathers murdered and crucified him for no reason”)

- Jews being evil (“offspring of promiscuity”)

Optional: The graphic organizer gives students space to reflect after learning about each historical form of antisemitism. If time permits, give students a few moments to reflect, either through writing or discussion, about what they have learned in this part of the lesson.

Transition: Explain that the second form of antisemitism we will be discussing is economic antisemitism. The image of the “greedy Jew” may be the most enduring antisemitic stereotype of all. It is during the medieval period that economic antisemitism began to take on forms that are familiar to us today.

6. HISTORICAL FORM OF ANTISEMITISM: ECONOMIC

Guiding Questions: How did Jews first become associated with money/money lending? What are some historical examples of religious antisemitism?

The notes below, as well as additional content, are presented through correlating slides in the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation. Please refer to the Antisemitism Glossary of Terms for additional definitions of the bolded words below.

● Starting in the 11th century, many medieval European legal systems prohibited Jews from owning land, farming, or joining craft guilds. These legal systems were based on the types of legal codes from the Roman period, like the Theodosian Code, which were designed to limit Jews religiously and economically.

● With few economic opportunities available, many Jews turned to marginalized occupations, such as tax/rent collecting and money lending on behalf of wealthier Christians. Many Christian lords would use Jews as middlemen to bypass the Christian religious prohibition on usury.

● As a result, the Christian populace depended on Jewish moneylenders, which resulted in resentment and hostility towards Jewish debt collectors (rather than the rulers who were enacting the taxes or charging high interest in the first place).

● Christian leadership exacerbated these tensions by positioning Jews as a scapegoat for the common person’s financial troubles. Though Jews were not the only ones involved in lending money at interest during the Middle Ages, eventually usury – and finance more generally – became identified as a “Jewish practice.”

● This association between Jews and money became deeply entrenched in Western society to the point where it is now a Jewish stereotype.

o Shylock – perhaps the most notorious Jewish moneylender – is a fictional character created by William Shakespeare. It’s important to note that Shakespeare debuted this play at a time when nearly no Jews were living in England – they had all been expelled 300 years earlier. However, the stereotype of the Jewish moneylender was so entrenched by this point that audiences didn’t need to have Jews around for the caricature to resonate.

o Hundreds of years later, Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company, propagated virulently antisemitic notions about Jews in his newspaper The Dearborn Independent, in the 1920s, drawing on medieval tropes that described Jews as ruthless, money-hungry, and in control of the world’s finances. The antisemitic content that was published in Ford’s newspaper had a significant impact because of its vast readership, with articles being picked up by other news outlets across America. Consequently, Ford’s published works played a role in the rise of antisemitism in the United States.

Share SOURCE 5: Excerpt from The International Jew.

Context:

The following excerpt is an illustration of the ideas propagated by Henry Ford in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent. He collected and published his articles in a book entitled The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem. The book became widely read, was translated into several languages, and served as a point of inspiration for later Nazi leadership.

Primary Source:

“Business is to [a Jew] a matter of goods and money, not of people. If you are in distress and suffering, the Jewish heart would have sympathy for you; but if your house were involved in the matter, you and your house would be two separate entities…the Jew would naturally find it difficult, in his theory of business, to humanize the house…he would say that it was only “business.” (June 5, 1920)[6]

Ask students:

● How are Jews being portrayed in this quote?

o Cruel, heartless, entirely driven by greed

o Incapable of displaying “sympathy” or “humanizing” situations if money is involved

Optional: The graphic organizer gives students space to reflect after learning about each historical form of antisemitism. If time permits, give students a few moments to reflect, either through writing or discussion, about what they have learned in this part of the lesson.

Transition: Explain that the third form of antisemitism we will be unpacking is political antisemitism. To understand the roots of this kind of anti-Jewish thought, we need to go back to the French Revolution and the rise of the modern nation-state.

7. HISTORICAL FORM OF ANTISEMITISM: POLITICAL

Guiding Questions: What is the “Jewish Question”? How did the political situation differ for the Jews of Western and Central Europe compared to the situation of those in Eastern Europe? How did the backlash to Jewish emancipation in Europe contribute to political antisemitism? What are some historical examples of political antisemitism?

The notes below, as well as additional content, are presented through correlating slides in the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation. Please refer to the Antisemitism Glossary of Terms for additional definitions of the bolded words below.

- In the late 1700s and 1800s, the cultural and political status of Jews in Western and Central Europe would begin to change.

- The French Revolution created a new category of “citizen” that granted equal rights to everyone (at least in theory). However, some French people wondered whether Jews were capable of really being “French enough” to be entitled to political rights like other citizens of France. This became known as the “Jewish Question.”

- In the end, France decided to emancipate its Jewish population in 1791. However, in return, Jews were expected to make changes to various aspects of their cultural and communal life (e.g., stop using traditional Jewish names, refrain from using Hebrew/Yiddish in business transactions, keep their Jewishness private and out of the public sphere).

- However, in Eastern Europe (where the majority of European Jews lived) the political situation was very different. Jews in Eastern Europe were not emancipated until 126 years later in 1917.

- In Imperial Russia in the 19th and early 20th centuries:

- Jews were only allowed to live in the so-called “Pale of Settlement.”

- Russian authorities encouraged antisemitic violence and riots known as pogroms.

- By the mid-19th century in Western and Central Europe, objections to emancipation began to grow. Resentment and fear helped fuel the prejudices that would manifest into political antisemitism.

- Resentment of perceived economic success among Jews fueled false notions that Jews were stealing jobs from Christians and were over-represented in important fields.

- As Jews became politically active, they were viewed as proponents of radical/dangerous political views – those held by whatever the powers that be feared.

- For example, because figures like Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky were of Jewish descent, this led people to closely associate Jews with communism (even though most Jews were not communists).

- More broadly, however, there were widespread conspiracy theories throughout Europe about Jewish governmental and economic control, which hinged on small numbers of Jews in positions of power.

- The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, published in Russia in 1905, is one of the most widely cited pieces of political antisemitism to this day.

- Despite efforts to assimilate and become part of their host societies, Jews continued to stay connected to their own communities and retain aspects of their cultural identities. This led critics to believe that Jews were benefiting from emancipation while remaining a separate group – a group whose loyalty would always be questioned. Jews, therefore, continued to be perceived as “other” and as a threat to European society.

Share SOURCE 6: Political Cartoon – “Metamorphosis”

Context:

The following political cartoon, printed in 1903, comes from a German weekly satirical magazine called Simplicissimus. [7] Explain that metamorphosis means a thing/person changing from one thing to something completely different (such as a caterpillar becoming a butterfly). Then have students take a look at the image below.

Primary Source:

First, consider guiding a discussion allowing students to share what they see – what do they notice when first examining this cartoon? Then ask students more specifically:

- What is going on in this cartoon?

- A Jewish immigrant is transforming himself from a pauper into a well-respected and affluent member of society

- What about the way the Jewish man is portrayed stays the same throughout the three pictures? What changes?

- The exaggerated and distorted features remain (hooked nose)

- The clothes are more expensive and modern

- The items he holds become more valuable and modern

- What is this cartoon implying about Jewish emancipation?

- That a Jew will always be a Jew – an “other” – no matter how much he changes externally and tries to assimilate

Reinforce the point that many in European society opposed emancipation because their prejudice against Jews led them to interpret Jewish efforts to join society as being motivated by ill intent. Additionally, the reference to the Jewish nose is based on pseudo-scientific notions of Jews being an inferior race, which will be addressed in the final form of antisemitism outlined in this lesson plan.

Optional: The graphic organizer gives students space to reflect after learning about each historical form of antisemitism. If time permits, give students a few moments to reflect, either through writing or discussion, about what they have learned in this part of the lesson.

Transition: Explain to students that the last form of antisemitism you’re going to examine is called racialized antisemitism. While political antisemites fear a “Jewish” political agenda for “world domination”, racial antisemites claim that there is a Jewish agenda for “racial domination.”

8. HISTORICAL FORM OF ANTISEMITISM: RACIAL

Guiding Questions: What term did Wilhelm Marr coin, and what did the term describe? How were the scientific concepts of natural selection and biological inheritance misappropriated by antisemites? What are some historical examples of racial antisemitism?

The notes below, as well as additional content, are presented through correlating slides in the Google Slides Deck for Classroom Presentation. Please refer to the Antisemitism Glossary of Terms for additional definitions of the bolded words below.

● In 1859, Charles Darwin debuted his theory of evolution and natural selection. In 1865, Gregor Mendel introduced the concept of biological inheritance – the basis for what we now call genetics.

● Racists and antisemites misappropriated these notions to support their beliefs in white superiority.

● In 1879, German journalist Wilhelm Marr introduced the term “antisemitism” to describe his opposition to Jews as a supposed inferior “race” (please reference the Appendix for more information). Soon, Marr’s new term was being used throughout Europe.

● Marr’s notion of Jews being an inferior race marked a dangerous turn. According to Marr, Jews were a problem because of innate and unchangeable biological differences.

● Racial antisemitism was the primary manifestation of antisemitism in Nazi Germany.

● According to Nazi racial theory, Jews constituted a biologically inferior race which was thought to corrupt the pure German-Aryan stock through “race-mixing” and intermarriage. It became extremely important to the Third Reich to distinguish between those with Jewish and “Aryan” ancestry.

● In 1935, the Nazi government passed the Nuremberg Laws, which legally made Jewish Germans different from non-Jewish Germans. They restricted marriages and sexual relations between those deemed racially German and those with Jewish backgrounds. Under the Nuremberg Laws, only “Aryans” were allowed citizenship. Jews were stripped of citizenship and denied their political rights, and their passports invalidated.

● Eventually, the Nazis passed more discriminatory laws that forced Jews out of many professions, severely limited their movements, and required them to self-identify in public with the infamous yellow stars.

● The Nazis made a great effort to define who was and was not racially acceptable. Their racialized understanding applied to: religious Jews, non-religious Jews, converts from Judaism to other religions, those who were not considered Jewish according to Jewish law but had some amount of Jewish ancestry.

Share SOURCE 7: Excerpt from a letter written by Adolf Hitler to Adolf Geimlich.[8]

Context:

In the politically unsettled period after World War I, the Bavarian state government in Germany established a group on May 11, 1919, to keep an eye on political groups and to carry out “educational work” in order to combat revolutionary activities among disgruntled army veterans. Adolf Hitler joined the “Information Department” as a propaganda writer and informant and participated in education courses organized by the department. Because of his noted rhetorical gifts, Hitler was appointed as a lecturer. He was asked to respond to Adolf Gemlich, a course participant, on September 16, 1919, on the government’s position on the so-called “Jewish Question.”

The letter is an early example of Hitler’s views on Jews before he became the leader of the National Socialist Democratic Party, also known as the Nazi Party, in 1921. The full letter builds on all of the types of antisemitism explored in this lesson. To analyze racial antisemitism, please examine the following excerpt with students:

Primary Source:

“Through a thousand years of inbreeding, often practiced within a very narrow circle, the Jew has in general preserved his race and character much more rigorously than many of the peoples among whom he lives. And as a result, there is living amongst us a non-German, foreign race, unwilling and unable to sacrifice its racial characteristics, to deny its own feeling, thinking and striving, and which nonetheless possesses all the political rights that we ourselves have. The feelings of the Jew are concerned with purely material things; his thoughts and desires even more so…His activities produce a racial tuberculosis among nations…”

Then, discuss the following questions with students:

- Where do you see racialized antisemitism expressed?

- “thousand years of inbreeding”, “the Jew has preserved his race and character”, “non-German, foreign race, unwilling and unable to sacrifice its racial characteristics”

- reveals the thought that Jews are a ‘foreign race’ with undesirable traits, and that they cannot be changed

- “the feelings of the Jew are concerned with purely material things”

- claims that the so-called greediness of Jews is in fact an inalterable racial characteristic

- “his activities produce a racial tuberculosis”

- Jews are described as causing disease in society – something malignant and insidious

- “thousand years of inbreeding”, “the Jew has preserved his race and character”, “non-German, foreign race, unwilling and unable to sacrifice its racial characteristics”

- What other types of antisemitism does Hitler express in this passage?

- “possesses all the political rights that we ourselves have”

- Disturbed that Jews have equal political rights – echoes the idea that Jews use political rights for nefarious gain

- “the feelings of the Jew are concerned with purely material things”

- ties in racialized perception of Jews with economic antisemitism

Share SOURCE 8: Speech by Ellison DuRant Smith”[9]

Context:

The Jewish immigrant population in the U.S. significantly grew between 1880-1924. Fears that immigrants posed a threat to the racial and cultural makeup of the U.S. led to efforts to keep Jews out. As a result, America created a new federal law that primarily aimed to exclude Eastern European Jews and Southern Italian Catholics from immigrating to the country: the 1924 Immigration Act. Many of the arguments put forward in support of the law, like this one, were explicitly racist. While the text does not name Jews specifically (aside from Son of a German Immigrant), it’s important to note that this is the kind of thinking that went along with racialized antisemitism – a belief in white superiority above ALL other “races”.

Primary Source:

“Who is an American? … If you were to go abroad and someone were to meet you and say, ‘I met a typical American,’ what would flash into your mind as a typical American, the typical representative of that new Nation? Would it be the son of an Italian immigrant, the son of a German immigrant, the son of any of the breeds from the Orient, the son of the denizens of Africa? …Thank God we have in America perhaps the largest percentage of any country in the world of the pure, unadulterated Anglo-Saxon stock…It is for the preservation of that splendid stock that has characterized us that I would make this not an asylum for the oppressed of all countries, but a country to assimilate and perfect that splendid type of manhood that has made America the foremost Nation in her progress and in her power… [L]et us shut the door and assimilate what we have, and let us breed pure American citizens and develop our own American resources.”

Then, discuss the following questions with students:

- How does DuRant Smith express racialized antisemitism?

- That only true Americans should only come from “pure” Anglo-Saxon (meaning mostly English) families. They even want to “breed” more of these “pure” Americans.

- This idea is part of a bigger way of thinking where people are judged and ranked based on their race. By saying what they think is the “right” race for America, they are automatically saying that other races are “wrong” or “less than.”

- How do these ideas suggest a specific, and potentially harmful, vision for who should be considered truly “American” and how immigrants should be treated?

- These ideas are harmful because they basically say that only people who are from a specific background (Anglo-Saxon) are truly American and valuable. Everyone else, especially immigrants, is seen as “less than” or a “problem” that needs to be changed.

Share SOURCE 9: Magazine cover of “La Libre Parole”[10]

As a final primary source analysis activity, ask students to look for the four forms of antisemitism they have learned about in a single source, which demonstrates the idea that these types of antisemitism are often interconnected and influence each other. Use the Library of Congress analysis method, “Observe, Reflect, Question,” to analyze the following magazine cover, which reflects many of the concepts from this lesson and can help students visually synthesize those ideas.

Context:

This magazine cover is from a French publication called La Libre Parole. It was printed on October 28, 1893 (just over 100 years after the emancipation of Jews in France).The editor and founder of this magazine was Edouard Drumont, who founded the Antisemitic League of France in 1889. Consider how this cover reflects antisemitic ideas held by parts of French society at the time.

Primary Source:

Step 1 – OBSERVE: Start by having students make observations, focusing on concrete details that they notice.

Observations may include: Tattered clothes, enlarged nose, animalistic/dehumanized features like claws, the money stuffed in his pockets and coming out of the world, he seems to be doing harm to the planet. He’s also in the dark – the sun is on the other side.

Step 2 – REFLECT: Next, ask students to reflect and use the prompt questions to help guide their thinking. What do the details suggest? What stereotypes are represented? In what ways are the four forms of antisemitism discussed in this lesson represented in this one image?

Reflections might include: If you recognize the stereotyped features, then we know this is a dehumanizing depiction of a Jew. Clearly, the illustrator believed that this man is harming the world in multiple ways. That he’s in the dark, along with the claw-like hands, suggests evil activity.

As for how the four types of antisemitism manifest in this image, here are some possible insights:

- Political antisemitism. The figure appears to be maliciously grabbing onto the globe, eagerly climbing his way as far as he can go. This reflects a perceived threat of Jewish world domination.

- Racialized stereotypes – the enlarged nose, the pointy beard, the beastly features – all exaggerated, and are reminiscent of the idea that Jews are less human and an inferior race trying to soil the purity of white Europeans.

- Economic stereotype of the greedy Jew with money stuffed in his pockets echoes the idea that Jews perform harmful economic activities.

- While not as overtly featured as the other forms of antisemitism, we can still see representations of religious antisemitism. First, there is the association between Jews and darkness, and therefore evil – a common trope in religious antisemitism. The man also covers his head, something that marks him as a religious Jew.

Step 3 – QUESTION: Finally, encourage students to ask additional questions to help further their learning. Possible questions might include: Why does the figure have exaggerated features? Why does he have on ragged clothes, while shown with an excessive amount of money in his pockets? Why is he illustrated as doing some sort of harm to the world?

Transition to Gallery Walk Activity: Explain to students that, like in the La Libre Parole image, the four forms of antisemitism continue to manifest in society, which will be demonstrated in the following activity. However, as important as it is to be able to recognize these influences, sometimes the way antisemitism is expressed in the current context does not fit neatly into the four historical forms. Today, we are seeing unprecedented levels of anti-Jew hate showing up in schools, sports, social media, and more, with the intent to hurt, intimidate, and marginalize Jews. In the following activity, we will refer to some examples as Evolving Anti-Jew Hate when they do not distinctly fit into the four categories we have learned about.

9. GALLERY WALK ACTIVITY

This activity may be used as a final assignment or as a lesson wrap-up. Students will apply what they have learned through direct instruction in the lesson to modern examples of antisemitism, or anti-Jew hate, that they will analyze independently.

Objective

Through close examination of primary source documents and collaborative group work, this activity will enrich student understanding of how the four forms of antisemitism have manifested in the past as well as the present.

Materials: Modern Antisemitism Gallery Walk: instructions, sources, questions, student note-catcher (PDF)

Set Up

Display the primary sources around the classroom. These primary sources should be displayed “gallery style,” at different stations in a way that allows students to disperse themselves around the room. The primary sources can be arranged in any order. They can be hung on walls or placed on tables. The most important factor is that the stations are spread far enough apart to reduce significant crowding.

There are 14 stations for this activity, so you may want to divide the class into groups and assign each group two or three stations, depending on the number of students in the class. Of course, you may decide to use fewer primary sources, depending upon the amount of time you have to spend on this lesson or what content you want to emphasize.

Instructions

Explain to the students that they will participate in a “gallery walk activity.” Students will move around from station to station, like in a museum or art gallery. They will review the source at each station and answer a few questions per station. Students should write their responses in the space provided on the Gallery Walk Note-Catcher (included in the PDF).

Alternative Gallery Walk Experience: Interactive Digital Gallery

Share a link to the Digital Version of the Modern Antisemitism Gallery Walk.

Then, instruct students to click on each image to interact with it by reading an example, answering a self-assessment question about the form of historical antisemitism shown, and considering discussion questions. Teachers can further assess understanding through class discussions or by collecting individual responses to provided prompts. Note that student responses entered on the slide identifying the historical form of antisemitism will not be available to the teacher.

10. CONCLUSION

Have students fill out the exit slip (PDF | Google Doc) or use the questions to hold a class discussion.

Appendix: Race vs. Ethnicity

The term ‘ethnicity’ falls short when describing Jewish identity. The more fitting, ancient term is Am (people). This category predates and differs from later social constructs like race, religion, and ethnicity, explaining why Jewish people don’t fit neatly into any of them.

However, to help students better understand how to define Jews as a group of people, it can be helpful to understand the difference between race and ethnicity, since Jews are often classified as an ethnic and/or a religious group, but NOT a race.

- Ethnicity refers to a people’s shared cultural identity, often based on factors such as ancestry, language, religion, customs, and a sense of common history or heritage. It distinguishes one group of people from another based on these cultural characteristics.

- The term race is often used to categorize and differentiate people based on physical traits such as skin color, facial features, and hair texture. However, it’s important to note that the concept of race is a social construct and not a scientifically valid biological category. All people are part of the human race.

It’s inaccurate to call Jews a race because they come from a wide variety of backgrounds and exhibit significant physical and visible diversity. This is why ethnicity is the preferred term to describe the Jewish people.

[1] Statues of Ecclesia and Synogoga in Freiburg Germany Cathedral Entrance, c. 1300

[2] A Law of Theodosius II, January 31, 439, Novella III: Concerning Jews, Samaritans, Heretics, and Pagans can be found at https://faculty.uml.edu/ethan_spanier/Teaching/documents/TheCodexTheodosianus.pdf

[3] The Jews in Christian Art: An Illustrated History (New York: Continuum, 1996), 337.

[4] Source: Wikipedia commons, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judensau#/media/File:Wimpfen-stiftskirche-judens.jpg

[5] Source: Shlomo Eidelberg, The Jews and the Crusaders: The Hebrew Chronicles of the First and Second Crusades (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1977), pg. 22.

[6] The Dearborn Independent, Issue June 5, 1920, pg. 23 https://archive.org/details/the-international-jew-henry-ford/page/n21/mode/2up

[7] Harris, Constance. The Way Jews Lived: Five Hundred Years of Printed Words and Images. McFarland, 2008. p. 335.

[8] Source of English translation: Jeremy Noakes and Geoffrey Pridham, eds., Nazism 1919-1945, Vol. 1, The Rise to Power 1919-1934. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1998, pp. 12-14.

[9] Speech by Ellison DuRant Smith, April 9, 1924, Congressional Record, 68th Congress, 1st Session (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1924), vol. 65, 5961–5962. https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1249

[10] Source:“Leur Patrie, (Their Homeland) La Libre Parole illustrée, No. 16, 28 October 1893 , Duke Library Exhibits, accessed July 8, 2013, http://exhibits.library.duke.edu/items/show/20981