The Failures of the Recovery from the Great Recession

Michael Meeropol and Jared Ragusett

When Barack Obama took over as President, there were fears that the United States was heading for a re-run of the Great Depression. The financial meltdown that became apparent during calendar year 2008 had sparked a dramatic recession – which has come to be known, with 20-20 hindsight, as the Great Recession. When Obama took office, the economy was hemorrhaging 700,000 jobs a month. The unemployment rate had climbed to 9 percent and was still increasing. Something had to be done.

Obama’s program passed the House and Senate in March of 2009. It was just enough to stop the bleeding and begin what turned out to be a painfully slow recovery. But because of a combination of Democratic timidity and Republican opposition, the size of the macroeconomic stimulation contained in the Recovery Act was much too small. In order to get the 60 votes needed to defeat a Republican filibuster, the Obama Administration had to pare back their proposed spending increases and tax cuts in order to satisfy the deficit hawks among the Democratic majority.

The result was a historically slow recovery which, the writers believe, was the reason the House flipped to the Republicans in 2010, the Senate flipped to the Republicans in 2014, and one of the reasons Donald Trump was elected President at the end of Obama’s two terms. This paper details the macroeconomic impact of the Obama Recovery program and compares several important macro-economic indicators from that recovery (2009-2017) to previous recoveries from recessions in the post-World War II era. The variables investigated include the ratio of investment to gross domestic product (GDP), the rate of growth of productivity, the ratio of consumption to GDP, the unemployment rate, the capacity utilization rate, the employment-to-population ratio, and the rate of growth of real GDP.

The results of the comparisons are striking. Real GDP growth was slow through 2016. Investment incentives were severely damaged by the housing bubble during the years 1995-2005, followed by the housing bubble meltdown during the years 2005-2009. Thus, during the Obama recovery, housing investment barely budged, reducing the overall level of investment. This led to a miniscule productivity growth rate. Meanwhile, consumption spending which is the key incentive for the revival of investment during business cycle upswings rose slowly as well. It also took a long time for the unemployment rate to fall to its pre-recession level.

This disappointingly sluggish recovery was the culmination of a number of long run trends that had slowed the economy during the entire period since the early 1970’s including the long-term slowdown in GDP growth per capita since the early 1980s.

During the Obama recovery, the unemployment rate declined very slowly. Obama won re-election but up and down the ballot – including in many state legislatures and the House of Representatives beginning in 2010 – Republicans cashed in on the impatience of citizens with the slow pace of recovery. The economy did not get back to “normal” until 2016 but it was too late for the Democrats. Trump was able to ride to a razor thin victory in part on the strength of disappointment by many people who had voted for Obama – both rural whites in key states like Wisconsin and Michigan who switched to Trump, as well as Black voters whose turnout fell in Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Milwaukee with devastating electoral consequences for three crucial battleground states (Krogstad and Lopez, 2017).

When President Obama took office, all eyes were focused on the short-run challenge of the Great Recession. Here’s how his Council Of Economic Advisers stated it, a year later, in the Economic Report of the President, 2010:

“In December 2007, the American economy entered what at first seemed likely to be a mild recession. … [R]eal house prices (that is, house prices adjusted for inflation) had risen to unprecedented levels, almost doubling between 1997 and 2006. The rapid run-up in prices was accompanied by a residential construction boom and the proliferation of complex mortgages and mortgage-related financial assets. The fall of national house prices starting in early 2007, and the associated declines in the values of mortgage-backed and other related assets, led to a slowdown in the growth of consumer spending, increases in mortgage defaults and home foreclosures, significant strains on financial institutions, and reduced credit availability.

By early 2008, the economy was contracting. Employment fell by an average of 137,000 jobs per month over the first eight months of 2008. Real GDP rose only anemically from the third quarter of 2007 to the second quarter of 2008.

Then in September 2008, the character of the downturn worsened dramatically. The collapse of Lehman Brothers and the near-collapse of American International Group (AIG) led to a seizing up of financial markets and plummeting consumer and business confidence. Parts of the financial system froze, and assets once assumed to be completely safe, such as money-market mutual funds, became unstable and subject to runs. Credit spreads, a common indicator of credit market stress, spiked to unprecedented levels in the fall of 2008. The value of the stock market plunged 24 percent in September and October, and another 15 percent by the end of January. [O]ver the final four months of 2008 and the first month of 2009, the economy lost, on average, a staggering 544,000 jobs per month, the highest level of job loss since the demobilization at the end of World War II. Real GDP fell at an increasingly rapid pace: an annual rate of 2.7 percent in the third quarter of 2008, 5.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008, and 6.4 percent in the first quarter of 2009” (ERP, 2010: 26-27).

Here is how President Obama himself described the crisis that greeted him when he took office:

“Last January, (2009) years of irresponsible risk-taking and debt-fueled speculation—unchecked by sound oversight—led to the near-collapse of our financial system. We were losing an average of 700,000 jobs each month. Over the course of one year, $13 trillion of Americans’ household wealth had evaporated as stocks, pensions, and home values plummeted. Our gross domestic product was falling at the fastest rate in a quarter century. The flow of credit, vital to the functioning of businesses large and small, had ground to a halt. The fear among economists, from across the political spectrum, was that we could sink into a second Great Depression” (ERP, 3).

Later in the same message he noted that there were also long-term problems that his administration had to confront:

“At the same time, long before this crisis hit, middle-class families were under growing strain. For decades, Washington failed to address fundamental weaknesses in the economy: rising health care costs, growing dependence on foreign oil, an education system unable to prepare all of our children for the jobs of the future. In recent years, spending bills and tax cuts for the very wealthiest were approved without paying for any of it, leaving behind a mountain of debt. And while Wall Street gambled without regard for the consequences, Washington looked the other way.

As a result, the economy may have been working for some at the very top, but it was not working for all American families. Year after year, folks were forced to work longer hours, spend more time away from their loved ones, all while their incomes flat-lined and their sense of economic security evaporated. Growth in our country was neither sustained nor broadly shared. Instead of a prosperity powered by smart ideas and sound investments, growth was fueled in large part by a rapid rise in consumer borrowing and consumer spending” (ERP, 5-6).

The Council of Economic Advisers elaborated a bit more on these long-run problems:

“…even before the crisis, the economy faced significant long-term challenges. As a result, it was doing poorly at providing rising standards of living for the vast majority of Americans…Beginning around 1970, slower productivity growth and rising income inequality caused incomes for most families to grow only slowly. After a half-decade of higher growth in the 1990s, the real income of the typical American family actually fell between 2000 and 2006” (ERP, 28).

As to what had caused the increase in inequality and slower productivity growth over the long run, the Council members were silent. They did, however, identify a rising share of debt-financed consumption as the problem for the decade since 2000:

“The expansion of the 2000s was fueled in part by high consumption. [T]he share of GDP that takes the form of consumption has been on a generally upward trend for decades and reached unprecedented heights in the 2000s. The personal saving rate fell to exceptionally low levels, and trade deficits were large and persistent. A substantial amount of the remainder of GDP took the form of housing construction, which may have crowded out other kinds of investment. Such an expansion is not just unstable, as we have learned painfully over the past two years. It also contributes too little to increases in standards of living. Low investment in equipment and factories slows the growth of productivity and wages” (ERP, 29-30).

In order to assess whether the Obama Administration’s plan for recovery from the Great Recession was a success or failure, one must first explain how to judge success or failure. In the Economic Report of the President for 2017, Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers certainly argued that what they had done since January 2009 had been a great success. Here is how they argued:

“Over the two terms of the Obama Administration, the U.S. economy has made a remarkable recovery from the Great Recession. After peaking at 10.0 percent in October 2009, the unemployment rate has been cut by more than half to 4.6 percent as of November 2016 … Real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita recovered fully to its pre-crisis peak in the fourth quarter of 2013, … As of November 2016, the economy has added 14.8 million jobs over 74 months, the longest streak of total job growth on record. Since private-sector job growth turned positive in March 2010, U.S. businesses have added 15.6 million jobs. Real wage growth has been faster in the current business cycle than in any since the early 1970s” [ERP: 217: 21].

The forceful response of the federal government to the crisis in 2008 and 2009 helped stave off a potential second Great Depression by setting the U.S. economy on track to rebuild, reinvest, and recover. Everything the Obama Council of Economic Advisers marked in their 2017 report is correct. Their emphasis on the importance of both the fiscal stimulus of the Recovery Act, and the temporary payroll tax holiday is not misplaced. Unfortunately, because of the political constraints on big deficits and the almost universal opposition of the Congressional Republicans, the Obama Administration had to be content with a fiscal stimulus, despite being the largest in the post-World War II economy, turned out to be woefully insufficient.

What was left out of the Council of Economic Advisers’ celebration of the successes of the post 2009 recovery was a sense of how the post 2009 period – the period of recovery according to the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Cycle Dating Committee – compared with recoveries from previous recessions. In general, it is essential that such comparisons be made across the board so that we can judge whether a particular set of policies was successful or not. The economy did recover. By the time Obama left office in 2017, all economic indicators were significantly better than they were when he took office. If that is all the evidence that is needed, then every President from Truman to Obama, except Jimmy Carter, George H.W. Bush and Donald Trump, represents an economic success story.

However, if we are going to use the comparative analysis, we have to compare apples to apples. Our comparative data will cover the quarters of recovery — from the trough to the peak. We will compare the data for the recovery from the Great Recession with previous recoveries going back to the 1961-70 period. As always, we will use the quarters of recovery as identified by the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee.

The next, and most significant question is: What are the standards of success? We have already indicated that the rate of growth of real GDP per capita is a crucial element of economic success. But growth has never been smooth. From the initial discovery back in 1819 that there is a “business cycle,” it has been apparent that economies organized by some variant of free-market capitalism grew by fits and starts surging forward in periods of growth, only to have them interrupted by what were called in the 19th century “crises.” Long run economic growth was powered by such surges of expansion. It is during these surges (officially called recoveries in the literature these days) that improvements in productivity occur for the most part because of high levels of private investment.

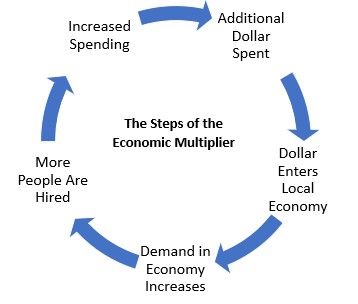

Investment and productivity growth represent the “supply side” of economic growth. But investment actually does dual duties because it is the most dynamic element in aggregate demand. When it is rising rapidly (evidenced by a high ratio of investment to GDP) it stimulates an increase in aggregate demand. When that ratio falls, it causes slowdowns and even recessions. These swings in investment have ramifications via the multiplier effect on consumption, by far the largest contributor to the “demand side” of economic growth. While investment changes introduce the major dynamic into the system, it is the growth of consumption that sustains it. Sometimes, export surges can play an important role and during wartime government spending plays a major role as well.

Meanwhile, productivity growth is the process that enables economic growth. All investments both in physical and human capital increase the capacity of the economy to produce. To the extent that the investment utilizes the newest technology, it plays a major role in increasing productivity. An increase in productivity makes it possible for wages to increase without cutting into profits, and for profits to increase without depressing wages. Thus, a higher rate of productivity growth during a period of economic recovery indicates that the economy is doing well, whereas a slowdown in productivity growth indicates the opposite. Though journalists, politicians and the public usually see GDP growth as the key to an economy’s success, from an economists’ point of view the gold standard of success is a high rate of productivity growth – because that facilitates higher economic growth and a rising standard of living.

So the rate of growth of productivity and the ratio of investment to GDP are both extremely important indicators of economic success. For investment, the standard of success is whether there is a relatively high ratio to GDP, which would show investment playing a very positive role. A relatively low ratio to GDP shows that investment is failing to provide the important dynamic element. The ratio of consumption spending to GDP shows how a growth spurt is sustained.

Our final standards of success relate to how close our economy comes to meeting its potential during a period of expansion. The usual standard of success, and the one that often has important political ramifications, is the civilian unemployment rate. Unemployed resources represent a waste of potential. In this paper, we choose to use three variables representing three different ways to measure the closeness to potential experienced during a recovery: unemployment, capacity utilization and the employment to population ratio. Though unemployment is the one most quoted in the media, there has always been an argument within the economics profession about how much unemployment is “voluntary.” Voluntary unemployment is not a waste of potential as the individual making the decision is unwilling to commit that potential to employment.

To further complicate the idea that the civilian unemployment rate measures a waste of human resources, we have the argument introduced by Milton Friedman that there is a “natural” rate of unemployment. That concept has been joined by the idea that there is a “non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment” (or NAIRU). At either or both of these rates, which have never been precisely identified numerically and which have changed from time to time, one could argue that the economy is not wasting resources because rates of unemployment below either the “natural” rate or the NAIRU are unsustainable.

In order to avoid arguing about how much of measured unemployment is truly involuntary, we also present the capacity utilization rate. This is a true measure of deficiency of aggregate demand because except for some minimal downtime for either routine maintenance or re-tooling, excess capacity is a clear waste of economic resources. Finally, the employment to population ratio avoids the knotty issue of how many people without jobs are truly not in the labor force. It captures the discouraged workers who never get counted in official unemployment statistics while still underestimating the under-utilization of human resources because it fails to measure involuntary part-time work. We believe all three of these statistics can give us a sense of how close to optimum utilization of resources an economy comes during a period of expansion. We also note that the impact of government spending, as evidenced by the data, was insufficient to propel a vigorous recovery given the severity of the downturn and the deep dive in the investment to GDP (I/GP) ratio.

With this plan, we can now turn to actually measuring the recovery from the Great Recession against previous recoveries starting with the 1961-70 recovery. The quarters between the troughs (1961, 1970, 1975, 1982, 1991, and 2001) and peaks (1969, 1973, 1980, 1990, 2001, and 2007) provide our data for the comparisons with the recovery from the Great Recession. In order to avoid the impact of compounding over recoveries of different lengths, we utilize averages over the course of each recovery as the basis for comparisons.

To assess the recovery from the Great Recession, we begin in the second quarter of 2009, and end when Obama left the White House in the first quarter of 2017. Even though the recovery did not end until the Covid-19 pandemic threw the economy into a very deep recession in the second quarter of 2020, our job is to describe the economy during Obama’s administration. First look at the ratio of gross investment to GDP. The reason we use gross investment rather than net investment is because even though the depreciation part of gross investment does not involve any net increase in the capital stock, the capital bought to replace that part of the capital stock that is “wearing out” will fix the newest technology and thus contribute to economic growth. In addition, the spending to replace wearing out capital has a multiplier effect just like any other spending.

Taking every recovery going back to 1961, all recoveries showed an average I/GDP ratio above 17 percent except for the 1961-70 recovery where investment as a percentage of GDP was below that level. The recovery from the Great Recession was significantly lower than the previous recoveries averaging just over 16 percent.

But that does not fully capture the seriousness of the problem. When President Obama took office, the I/GDP ratio was 12.7 at the trough of the Great Recession. Unfortunately, unlike some earlier recessions (1974 and 1982 for example), when the ratio rebounded dramatically (reaching 17% in 1976 and over 20% in 1984). It took three years between 2009 and 2012 for the I/GDP ratio to reach 15.5%. It averaged only 16.2 percent of GDP for the entire period through 2017Q1 and in fact never broke 18% until after 2017. The reason for the sluggish recovery of investment is easy to see, the fall in residential housing investment that had been the proximate cause of the Great Recession. From a ratio of 6.6 % of GDP in 2006, housing investment plummeted to 2.6 % of GDP at the depth of the Great Recession and had slowly climbed only to 3.9 % of GDP by the end of President Obama’s second term. This ratio was lower than the previous nadir of residential investment as a percentage of GDP at the end of the 2001 recession (4.8%). If housing investment had just returned to that level, overall investment would have broken 18% significantly earlier.

Because investment is the driving force of the economy’s dynamic, we should expect that the sluggish recovery of the I/GDP ratio to have a significant impact on the rate of growth of productivity, the rate of growth of the economy, and the variables that measure how close to potential (sufficiency of aggregate demand) the economy is. Sure enough, the numbers bear this out. The rate of growth of productivity was most dramatic in the 1961-70 recovery, averaging over 3 percent per quarter. After disappointing numbers in the 1970s, the rate of growth of productivity averaged 2 percent or higher per quarter over the three recoveries beginning in 1982 – averaging 2.6 percent between 2001 and the end of 2007 which was the peak before the Great Recession. Unfortunately, the disappointing numbers from the 1970s returned with a dismal 1.1 percent average in productivity growth over the entire recovery period through the first quarter of 2017. That coupled with disappointing numbers for unemployment, (7.3 percent average) capacity utilization (75.8 percent average) and especially the employment-to-population ratio (58.9 percent average) combine to explain the disappointing overall per capita GDP growth.

Except for the recovery from the dot-com bubble recession (2001-2007), every recovery going back to the 1960s had experienced per capita GDP growth averaging 2.5 percent or better. But as the economy struggled to slowly rise from the trough of the Great Recession the rate of growth of per capita GDP averaged only 1.4 percent per quarter through 2017. That is even lower than the 1.9 percent in the 2001-2007 recovery.

The unemployment rate had been trending upwards since the 1961-1970 recovery, averaging over six percent per quarter beginning with the 1971-74 recovery until the recoveries of 1991-2000 and 2001-2007 where the rates were 5.5 percent and 5.3 percent respectively. Similarly capacity utilization has been trending down since the robust 86 plus percent in the 1961-70 period. After an upward move in the 1991-2000 recovery, it resumed its downward trajectory, ending up averaging the lowest since World War II over the recovery from the Great Recession. The same trend appears in the employment-to-population ratio, which jumped up to an average of 63 percent in the 1991-2000 recovery only to average 58.9 percent in the recovery since 2009.

This is where the insufficiency of the macro-economic stimuli engaged in by the Obama administration (and we repeat, we understand how they were politically constrained, especially after “the worst” of the Great Recession had passed and the economy was clearly in recovery) reveals itself. The extraordinary nature of the deep dive that occurred in investment and the growth of GDP called for a significantly bigger stimulus to aggregate demand than in previous periods. Government spending at levels similar to previous business cycle recoveries was not enough.

The only departure from previous government stimuli during recoveries was the increase in transfer payments. Unfortunately, this only has a multiplier effect through its impact on consumption but the data shows that the ratio of consumption to GDP was less than a half a percent higher than in the previous recovery. There is no question that the federal spending stimulus would have had to be much higher than it was for the recovery to have any hope of being as good as previous ones.

We contend that despite the laser-like focus of the Obama Administration on getting the economy moving again as symbolized by the Recovery Act’s unprecedented explicit efforts to use fiscal policy to induce a robust recovery (the Congressional Budget Office concluded that the Recovery Act provided a stimulus spending level of $739 billion), it did not come close to closing an aggregate demand shortfall that was estimated conservatively at $1.2 trillion.

It is also important to add that the Federal Reserve’s expansive monetary policy seemed to have no positive impact on investment, particularly the interest sensitive housing sector, given the free fall of the housing market after the collapse of the bubble – almost a textbook example of the simple argument that the Fed cannot push on a string.

Initially, the Recovery Act did what it was supposed to. The federal budget deficit ballooned to 9 percent of GDP in 2010 and the unemployment rate began to fall. But when the Recovery Act spending began to peter out, the Republicans who had taken control of the House in 2010 forced the Obama Administration to compromise and agree to a set of spending restraints knows as a “sequester.” The result was that the federal deficit, the major impetus to the economy when investment spending lags, fell so that by 2013 it was only a bit over 4 percent of GDP.

Thus, it took all the way to 2015 for the unemployment rate to get back to what it had been before the Great Recession. This long, laborious struggle by the economy just to get back to square one, no doubt due to the fact that the I/GDP ratio never achieved the peak it had reached in the previous four recoveries.

In this extraordinary period when the economy was attempting to dig itself out of the hole created by short-run financial meltdown and the bursting of a housing bubble that left residential investment way below recent levels for the entire course of the recovery, a much higher level of government stimulus would have been necessary. Obviously, the Obama Administration and its allies in Congress cannot be totally faulted for this because after 2010, Republicans were in control of the House of Representatives and after 2014, Republicans took control of the Senate as well. The Obama Administration did make efforts to get an infrastructure bill passed a number of times but the Republicans in Congress blocked them. Despite wholesale opposition, the Obama Administration was able to increase stimuli via a temporary suspension of two percent from the Payroll Tax. They were able to do this by delaying the automatic expiration date of the George W. Bush tax cuts, scheduled to sunset after 2010, for two years which got Congressional support for the payroll tax holiday and expansion of unemployment compensation. After 2013, some of those tax cuts were made permanent while the payroll tax holiday ended. Unfortunately, the initial proposal for the Recovery Act was much too low and in order to get 60 votes in the Senate to break a Republican filibuster against it, the initial proposal was cut back slightly.

The economy is not just numbers like GDP and Investment. Ultimately, the key to economic well-being is the real income of ordinary Americans. We believe that the statistic identified as the median income of year-round full-time workers is indicative. Beginning in the third quarter of 2009, by the first quarter of 2017, the weekly real earnings of workers over 16 had risen the grand total of 2.03% for an average of about .28% a year. These were significantly lower than in previous recoveries though it is fair to say, median income growth was very slow for the entire period after 1980.

With 20-20 hindsight, the initial bill should have had a section that called for spending the same amount again if after two years, the unemployment rate had not fallen substantially. Given that previous deep sharp recessions (1974, 1981-82) experienced strong rapid recoveries, such a provision might have been sold as “insurance” against such a sluggish recovery and might have passed. But of course, hindsight is always 20-20.

The unfortunate result of the fact that the recovery from the Great Recession was much too slow and that median incomes of ordinary Americans hardly budged during the recovery was the high level of dissatisfaction within large swaths of the American people. Though there are many reasons for the surprise victory of Donald J. Trump in the 2016 election, one element that clearly contributed to it was the failed recovery from the Great Recession.

References

ERP (2010). Economic report of the President. Council of Economic Advisers.

ERP (2017). Economic report of the President. Council of Economic Advisers.

Krogstad, J.M. & Lopez, M.H. (2017, May 12). “Black voter turnout fell in 2016, even as a record number of Americans cast ballots.” Pew Research Center.