New Jersey Council for the Social Studies

Engaging High School Students in Global Civic Education Lessons in U.S. History

The relationship between the individual and the state is present in every country, society, and civilization. Relevant questions about individual liberty, civic engagement, government authority, equality and justice, and protection are important for every demographic group in the population. In your teaching of World History, consider the examples and questions provided below that should be familiar to students in the history of the United States with application to the experiences of others around the world.

These civic activities are designed to present civics in a global context as civic education happens in every country. The design is flexible regarding using one of the activities, allowing students to explore multiple activities in groups, and as a lesson for a substitute teacher. The lessons are free, although a donation to the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies is greatly appreciated. www.njcss.org

Era 14 Contemporary United States: Domestic Policies (1970–Today)

During the last quarter of the 20th century and the first quarter of the 21st century, the United States and the world experienced rapid changes in the environment, technology, human rights, and world governments. During this period there were three economic crises, a global pandemic, migrations of populations, and a global pandemic. There were also opportunities in health care, biotechnology, and sustainable sources of energy. The debate over individual freedoms, human rights, guns, voting, affordability, and poverty were present in many countries, including the United States.

Activity #1: Miranda in some countries accused must prove they are innocent

As the United States became more diverse and inclusive after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, our population became divided on the assimilation of immigrants and restricting the number entering the United States. The civil liberties in our constitution become challenged as people wanted “law and order.” One civil liberty that has weakened over time is the “Miranda Warning” from the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Miranda v. Arizona, (1966).

“Ernesto Miranda was convicted on charges of kidnapping and rape. He was identified in a police lineup and questioned by the police. He confessed and then signed a written statement without first having been told that he had the right to have a lawyer present to advise him (under the Sixth Amendment) or that he had a right to remain silent (under the Fifth Amendment). Miranda’s confession was later used against him at his trial and a conviction was obtained. When Miranda’s case came before the United States Supreme Court and the Court ruled that, “detained criminal suspects, prior to police questioning, must be informed of their constitutional right against self-incrimination and the right to an attorney.” The court explained, “a defendant’s statement to authorities are inadmissible in court unless the defendant has been informed of their right to have an attorney present during questioning and an understanding that anything, they say will be held against them.” The court reasoned that these procedural safeguards were required under the United States Constitution.”

Miranda rights typically do not apply to individuals stopped for traffic violations until the individual is taken into custody. There are four rights that are usually read to someone about to be interrogated or detained against their will.

- The Right to Remain Silent: You are not obligated to answer any questions from law enforcement.

- Anything You Say Can Be Used Against You: Statements you make during questioning can be presented as evidence in court.

- The Right to an Attorney: You have the right to consult with a lawyer before answering questions and to have one present during interrogation.

- If You Can’t Afford a Lawyer, One Will Be Provided: This guarantees access to legal counsel, regardless of your financial situation.

This basic civil liberty has weakened over time giving more power to the police (government). This power has resulted in forced confessions, false statements by the police, accusations of resisting arrest by not providing the police with basic information, and delaying the reading of the Miranda Warning. In Vega v. Tekoh (2022), the U.S. Supreme Court held, Miranda warnings are not rights but rather judicially crafted rules, significantly weakening this civil liberty as a constitutional protection.

Japan’s Criminal Justice System

Unlike in the United states, in Japan, individuals are presumed guilty. There is no right to remain silent or the offer of a lawyer. Many people, including juveniles, may be detained for months as the authorities try to obtain a signed confession. Most people are unaware of these practices because of Japan’s reputation as a democracy and their international human rights record.

“Tomo A., arrested in August 2017 for allegedly killing his six-week-old child by shaking. He spent nine months in detention awaiting trial, and during that time, prosecutors told him that either he or his wife must have killed their baby and his wife would be prosecuted if he did not confess. He was acquitted in November 2018.”

Bail is not an option during the pre-indictment period and it is frequently denied after a person is indicted of a crime. Bail, when granted, is limited to a maximum of 10 days with an appeal for an additional extension of up to 23 days. Individuals who are released, are watched closely and new arrests are fairly common.

“Yusuke Doi, a musician, was held for 10 months without bail after being arrested on suspicion of stealing 10,000 yen (US$90) from a convenience store. His application for bail was denied nine times. Even though he was ultimately acquitted, a contract that Doi had signed with a record company prior to his arrest to produce an album was cancelled, resulting in financial loss and setting back his career.”

Police often use intimidation, threats, verbal abuse, and sleep deprivation to get someone to confess or provide information. The Japanese Constitution states that “no person shall be compelled to testify against himself” and a “confession made under compulsion, torture or threat, or after prolonged arrest or detention shall not be admitted in evidence.”

The accused are not allowed to meet, call, or even exchange letters with anyone else, including family members. Many individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch cited this ban on communications as a cause of significant anxiety while in detention.

In 2015, Kayo N. was arrested for conspiracy to commit fraud. Kayo N. said that she worked as a secretary at a company from February 2008 to October 2011. In December 2008, the company president asked her to become the interim president of another company owned by her boss while a replacement was sought. She said that she was unaware that the company only existed on paper and that her boss had previously been blacklisted from obtaining loans. After her arrest and detention, the judge issued a contact prohibition order on the grounds that she might conspire to destroy evidence. Kayo N. was not allowed to see anyone but her lawyer for one year, could not receive letters, and could only write to her two adult sons with the permission of the presiding judge.

She said: “After I was moved to the Tokyo detention center, I was kept in the “bird cage” [solitary confinement] from April 2016 to July 2017. It was so cold that it felt like sleeping in a field, I had frostbite. I spoke only twice during the day to call out my number. It felt like I was losing my voice. The contact prohibition order was removed one year after my arrest. However, I remained in solitary confinement.

Kayo N. said she did not know why she had been put in solitary confinement. She says that police also interrogated her sons to compel her to confess. The long trial process also exacerbated financial hardships. She was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment.”

Japan has a 99.8 percent conviction rate in cases that go to trial, according to 2021 Supreme Court statistics.

Questions:

- Should the rights of an individual receive greater or lesser weight than the police powers of the state when someone is accused of a criminal offense?

- How can the Miranda rights be protected and preserved in the United States or should they be interpreted and implemented at the local or state level?

- How is Japan able to continue with its preference for police powers when international human rights organizations have called for reform?

- In the context of detainment by federal immigration officers in the United States in 2026, do U.S. citizens (and undocumented immigrants) have any protected rights or an appeal process when detained without cause?

How to Interact with Police (Video, 20 minutes)

The Erosion of Miranda (American Bar Association)

Vega v. Tekoh(2022)

Japan’s “Hostage Justice” System (Human Rights Watch)

Caught Between Hope and Despair: An Analysis of the Japanese Criminal Justice System (University of Denver)

Activity #2: Gun laws in United States and New Zealand

United States

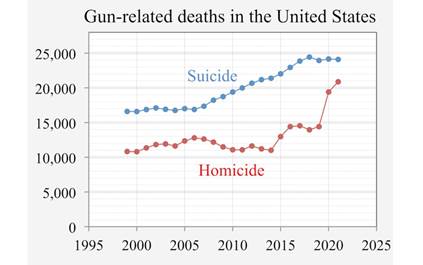

Since 1966, 1,728 people have been killed and 2,697 injured in mass public shootings in the United States. The definition of a mass shooting is three or more individuals being killed. (Investigative Assistance for Violent Crimes Act, 2012) The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation does not define a mass shooting with a specific number of deaths. Technology, especially the production of ‘ghost guns’ with 3-D printers has contributed to gun violence. Handguns are used in 73% of mass shootings and rifles, shotguns, assault weapons, and multiple weapons are also used.

Before 2008, the District of Columbia prohibited the possession of usable handguns in the home. This was challenged by Dick Heller, a special police officer in the District of Columbia who was licensed to carry a firearm while on duty. He applied to the chief of police for permission to have a firearm in his home for one year. The chief of police had the authority to grant a temporary license but denied the license to Dick Heller, who appealed the decision in a federal court.

The Second Amendment states that “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Several state constitutions give citizens the right to bear arms in defense of themselves and outside an organized state militia. Individuals used weapons against Native Americans and enslaved individuals.

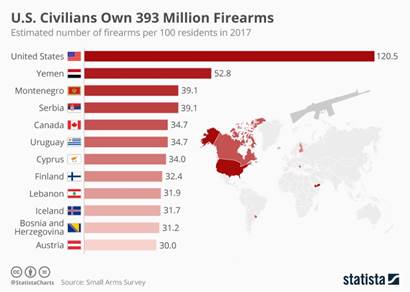

The United States has the highest number of registered guns per person in the world. Estimates range from 300 million (one per person) to over 400 million. Even with effective legislation on restricting guns, these weapons would still be availabile. Approximately 10 million firearms are produced annually.

A discussion in your classroom might focus on the debate within the state legislatures during the ratification of the Constitution regarding the use or arms for a state militia and the right of individuals to carry weapons for hunting. The Bruen decision (2022) requires that gun laws today need to be consistent with the historical understanding from when the states ratified the Bill of Rights.

1. Is this requirement possible and relevant? In 1789 people hunted for their food and today people go shopping in supermarkets. In 1789, the federal government relied on states to support an army and today we have a highly trained military.

2. Has the technology on producing guns change the right to keep and bear arms? Assault weapons and the production of ghost guns did not exist 200 years ago.

3. Should the need to restrict the right to keep and bear arms be consider as a result that the population of the United States is now over 300 million? A significant portion of the population lives in urban areas with high-rise apartment complexes. Should the history of previous centuries alongside the mass shooting events of the 21st century, be careful considered in the debate to restrict gun ownership?

New Zealand

March 15, 2019 marks one of the darkest days in New Zealand when 51 people were killed and 50 others wounded when a gunman fired at two mosques in the city of ChristChurch. This was the worst peacetime mass shooting in New Zealand’s history. Within one month New Zealand’s Parliament voted 119-1 on a nationwide ban on semi-automatic weapons and assault rifles. The gun reform law also set up a commission to establish limits on social media, accessibility to weapons, and education. In addition to the sweeping reform of gun laws, a special commission is being set up to explore broader issues around accessibility of weapons and the role of social media.

Australia also introduced a ban on automatic and semi-automatic weapons and restrictive licensing laws after a mass shooting in 1996. Some states in the United States have enacted strict laws restricting ghost guns (New Jersey, Oregon) and automatic weapons (New Jersey). However, the debate has been contentious in these states and the almost unanimous vote in New Zealand is not likely in the United States.

Questions:

- How significant would restrictive legislation in the United States be in curtailing mass shootings and/or murders?

- In addition to the influence of the gun lobby in the United States, what is the next most powerful influence against gun reforms in the United States?

- Is it possible for states to have their own restrictive gun laws with the Bruen decision by the U.S. Supreme Court?

- Why do you think restrictive gun laws were enacted in New Zealand and Australia? (absence of a constitutional protection, common national identity, religious beliefs, culture, leadership by the government, public outrage, etc.)

- As a class, do you think gun reform laws in the United States are possible in the next 5-10 years?

District of Columbia v. Heller(2008)

Why Heller is Such Bad History(Duke Center for Firearms Law)

15 Years After Heller: Bruen is Unleashing Chaos, But There is Hope for Regulations(Alliance for Justice)

Mass Shooting Factsheet (Rockefeller Institute of Government)

Gun Ownership in the U.S. by State (World Population Review)

Gun Control: New Zealand Shows the Way(International Bar Association)

Firearms Reforms (New Zealand Ministry of Justice)

Activity #3: Affordability in the USA and Italy.

United States

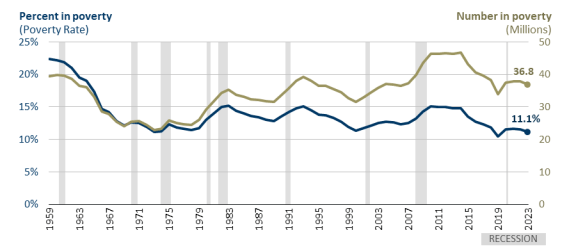

According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), poverty has decreased in the United States from 15% 2010 to 11.1% in 2023, and in 2025 it is estimated to be 9.2%. Poverty is measured both as the number of people below a defined income threshold of $31,200 for a family of four in 2025 (absolute poverty or below the poverty line) and as a quality of life issue for people living in a community. (relative poverty) Source

Figure 1. Official Poverty Rate and Number of Persons in Poverty: 1959 to 2023

(poverty rates in percentages, number of persons in millions; shaded bars indicate recessions)

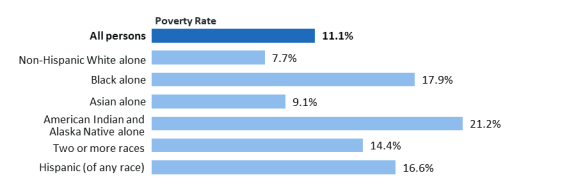

Unfortunately, poverty rates vary by sex, gender, and race. The current ‘affordability’ crisis in the United States is an example of relative poverty with many complex factors contributing to it.

Figure 4. Official Poverty Rates by Race and Hispanic Origin: 2023

A general guideline for budgeting housing expenses (rent or mortgage) is 33% of a household income, although expenses for rent and mortgage will vary by zip code. The U.S. Census Bureau reported a per capita income of $43,289 (in 2023 dollars) for 2019-2023, while the Federal Reserve Bank reported a personal income per capita of $73,207 for 2024. Personal income is the total earnings an individual receives from wages, salaries, investments and government benefits before income taxes are deducted. For your discussion consider the following based on $73,207 for one person. A family of four income with two working adults would be $146,414.

Federal Taxes (22%) $16,104

NJ State Taxes (5%) $3,660.

Housing (33%) $24,156 ($2,000 a month)

Food (10%) $7,300 ($140 per week)

Auto Transportation (15%) $10,980

Discretionary Spending (15%) $10,980

Consider the discretionary expenses in your family for phones, cable and internet, car lease or loan payments, vacation, gifts, savings, clothing, credit card debt, education, etc.

As incomes rise people spend more money on food, but it represents a smaller share of their income. In 2023, households with the lowest incomes spent an average of $5,278 on food representing 32.6% of after-tax income. Middle income households spent an average of $8,989 representing 13.5% of after-tax income) and the highest income households spent an average of $16,996 on food representing 8.1 percent of after-tax income.

The starting salary for many individuals with a four-year college education is about $70,000. Living in New Jersey is more expensive than living in many other states but for the purpose of discussion, we will use New Jersey as our reference.

Italy

The poverty rate in Italy is 9.8%, similar to the rate in the United States. However, the poverty rate for individuals below the poverty line (income level) is 5%. Approximately half of the people in poverty are living in southern Italy. Two contributing factors are the continuing effects from the government shutdown during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and an aging population. These factors are related to Italy’s high unemployment rate of 6.8% (2024), which is higher than the 4.4% in the United States, weak GDP growth of less than 1%. With a per capita income of $39,000 USD, Italy also has an affordability crisis. The per capita income in Italy is about one-half of the per capita income in the United States.

In 2017, Italy approved a program of “Inclusion Income: which has been reformed twice since its adoption. Under the current (2024) “Income Allowance” about 50% of the population receives supplemental income. This program supports economic upward mobility through education and health care. Italy has partnered with the World Bank to support this program. Another benefit of the program is that poverty is not increasing and will be significantly reduced over time.

Questions:

- Is the solution for affordability a higher minimum wage, lower taxes, price controls on food and housing, a guaranteed minimum income, or something else?

- Is it possible to lower the poverty rate through education and effective budgeting skills?

- Where do most Americans overspend their money and how can this best be corrected?

- Are transfer payments by the government (child care, Medicaid, Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, SNAP), wasteful or helpful?

- As a policy maker in the federal or state government, what is the first action you would take to address the affordability problem in the United States or in your state?

- How is Italy addressing the causes of poverty in addition to providing a guaranteed income to support people and families with basic needs?

- How is Italy financing its program and is it cost effective?

- Are tax cuts or tax credits an effective policy to assist people facing affordability issues?

7 Key Trends in Poverty in the United States (Peter G. Peterson Foundation)

United States Country Profile (World Bank)

Poverty in the United States: 2024(U.S. Census)

2025: Kids Count Data Book (Annie E. Casey Foundation)

Italy’s Poverty Reduction Reforms(World Bank)

Evolving Poverty in Italy: Individual Changes and Social Support Networks(Molecular Diversity Preservation International, MDPI)

ISTAT Report: Poverty and Inequalities in Italy(EGALITE)

Italy’s Fight Against Global Poverty (The Borgen Project)

Activity #4: Voter Participation in USA and Greece

United States

Voter participation is based on many factors and the structure for electing representatives to Congress is complex and is related to the selection of electors in each state who vote for the president and vice-president every four years. In the first 25 years of the 21st century, voting has changed significantly in the United States regarding the way citizens vote and in the definition of a legally registered voter. In this activity, you will discuss and analyze the issues of gerrymandering, voter participation, and voter eligibility in the United States and compare our process with voter participation in Greece.

Gerrymandering:

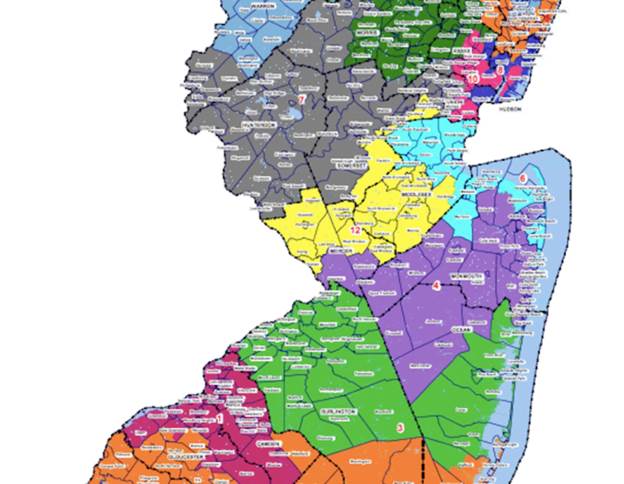

Every 10 years, states redraw the boundaries of congressional districts to reflect population changes reported in the census. The purpose is to create districts/maps that elect legislative bodies that fairly represent communities. In 1929, the number of representatives for the population was set at 435. In the 1920s the debate about fairness was between urban and rural populations and today it is between racial and ethnic populations and political parties. This practice is ‘partisan gerrymandering’. In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause, that gerrymandered maps cannot be challenged in federal court.

Partisan gerrymandering is undemocratic when one party controls the process at the state level. Cracking is a strategy that places some voters in districts that are a a distance from their immediate geographic area, making it very difficult for them to elect a candidate from their political party preference or racial or ethnic group. The majority of voters in New Jersey favored the Democratic Party making it difficult to establish districts that are fair to residents who favor the Republican Party. The issue of fairness may conflict with what is considered legal, fair, and constitutional. This complexity should engage students in a lively debate regarding its relationship to voter participation.

After the 2020 census, Republicans controlled the redistricting process in more states than Democrats.

In Illinois, the Democratic majority designed the congressional map limiting Republicans to just 3 of 17 seats. The use of algorithms and artificial intelligence are assisting the drawing of partisan districts. South Carolina offers an example of racial bias in a reconfigured district in Charleston that removed many Black voters. However, when challenged under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the new design was defended based on politics rather than race or ethnicity.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act has been challenged in the federal courts and amended in 1982. The decision in Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous Development Corporation (1977) is the current standard regarding a requirement that discrimination would actually harm minority voting strength. This standard is more difficult to prove than an expectation that it might be discriminatory. In 2013, a requirement of photo identification in North Carolina was challenged in Shelby County v. Holder but there was insufficient evidence to meet the standard of discrimination.

Voter Registration and Eligibility:

Voting is basically controlled by the states, although they must be in compliance with federal laws regarding elections for Congress and the President. Every state, except North Dakota, requires citizens to register to vote. Voter registration can help prevent ineligible voters from voting. The registration process generally includes identification to validate age, residency, citizenship, and a valid signature or state ID. Registration also prevents people from voting multiple times and someone stealing their ballot and submitting it.

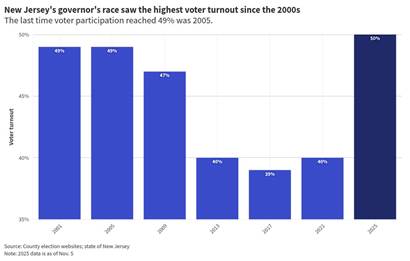

Voter Participation:

There are different ways to measure voter participation regarding trends over time, in years when voters elected a governor or president, by age, race, or ethnicity, when a popular issue was on the ballot, etc. In New Jersey, voter participation is generally less than 50% of the population.

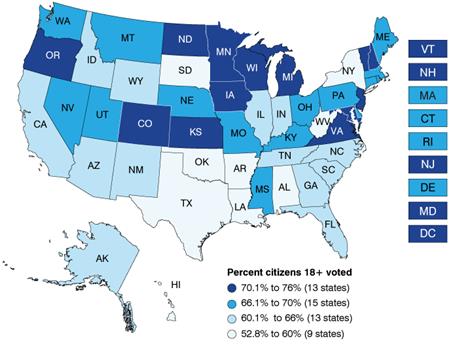

In presidential elections, the voter turnout is between 60% and 70% on average. New Jersey has more than 70% of the population voting. Efforts to increase voter participation include early voting, mail-in ballots, and extended hours at polls.

Greece

Voter Participation:

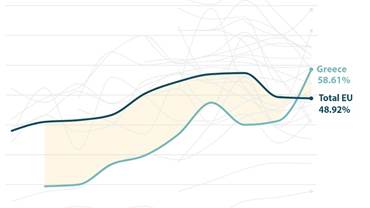

Voter participation rates in the European Union are less than 50%. The democracies in most European Union countries have multiple political parties, unlike the United States which has two major parties. One of the reasons for the lower voter turnout is pessimism regarding both the candidates and issues. The voter participation rate in Greece is above the average of EU countries, and we will use this as our case study.

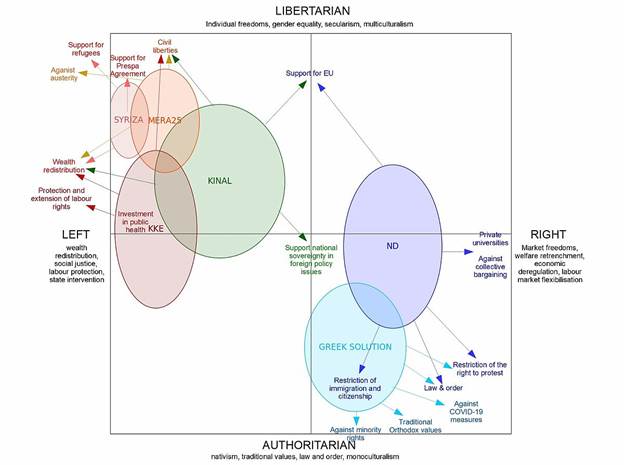

In 2025, Greece’s political scene is dominated by the center-right party, New Democracy. The largest opposition party is the SYRIZA, a left wing of progressive party. Some of the current problems or issues facing the people in Greece are high prices, health care, and public safety. The Russia-Ukraine War and the authoritarian government in Turkey are also concerns.

The survey revealed a significant and concerning trend, with recent elections showing record-high abstention rates—46.3% in the June 2023 national elections and 58.8% in the June 2024 European elections. A recent scandal in Greece also impacted the election involving a spyware tool, Predator, which has been associated with associates of the current Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis. The illustration below is a guide to the numerous ideologies of the political parties in Greece. There are also restrictions on the freedom of the press, which fosters a credibility gap between the people and their government.

Questions:

- Why do you think the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial gerrymandering is illegal but partisan gerrymandering is permitted?

- In Rucho, the U.S. Supreme Court acknowledged that partisan gerrymandering may be “incompatible with democratic principles.” Do you agree or disagree? Explain your answer.

- Even though gerrymandering may benefit one political party over another, it is the people who elect the state representatives who draw the maps for the congressional districts. Is this practice fair or unfair?

- What is the best way to significantly increase voter participation in the United States, Greece, and other countries?

- Are the requirements for voter registration and proof of identification significant restrictions on voters?

- To what extent is voting in New Jersey fair for all eligible voters?

Election Guide: United States(International Foundation for Electoral Systems)

Election Guide: Greece(International Foundation for Electoral Systems)

United States(Freedom House)

The Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929(U.S. House of Representatives)

Freedom to Vote Act(Brennan Center for Justice)

Greece(Freedom House)

Why Greeks are staying Away from the Polls: Key Insights into the 2023-2024 Survey(Kapa Research)