Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 By Dr. Stephen Kotkin, Princeton University

Application to European and World History by Hank Bitten

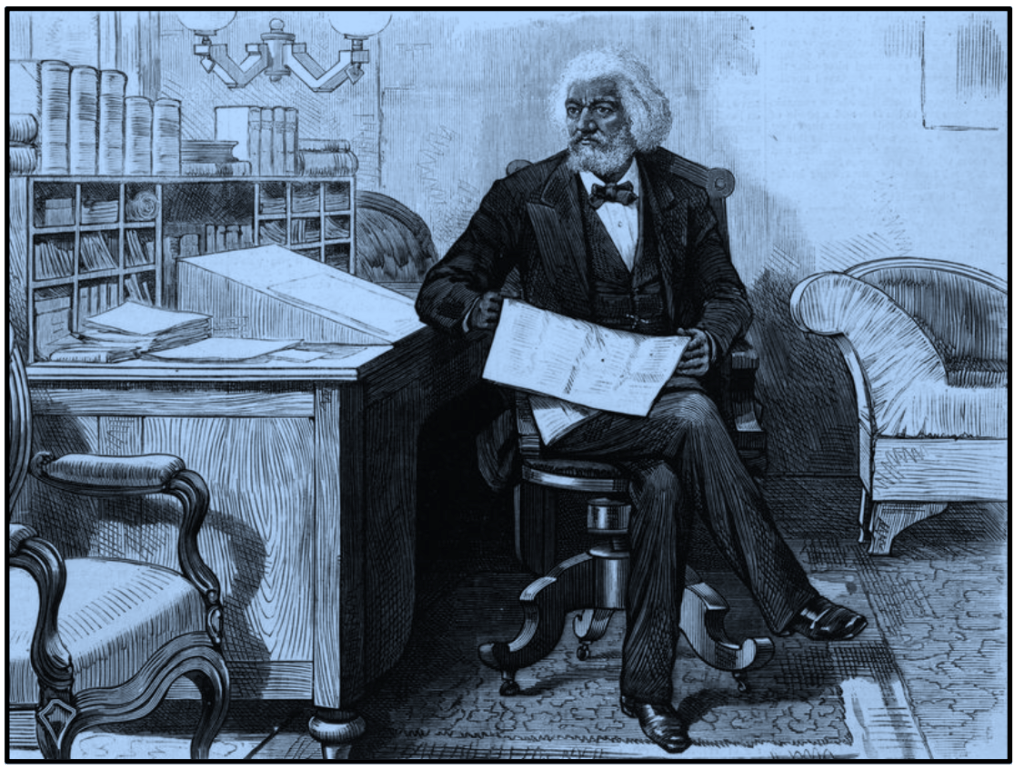

The opening sentence, the thesis statement, by Dr. Kotkin is capitalized: “JOSIF STALIN WAS A HUMAN BEING.” This is supported by the evidence that he carried documents wrapped in newspapers, was an avid reader with a personal library of more than 20,000 books, and a man who enjoyed his tobacco from Herzegovina. Throughout the book there are the details of the floor plans of his apartments and hunting lodge, passion for his 1933 Packard Twelve luxury car and relationships with his mother, two wives, and children.

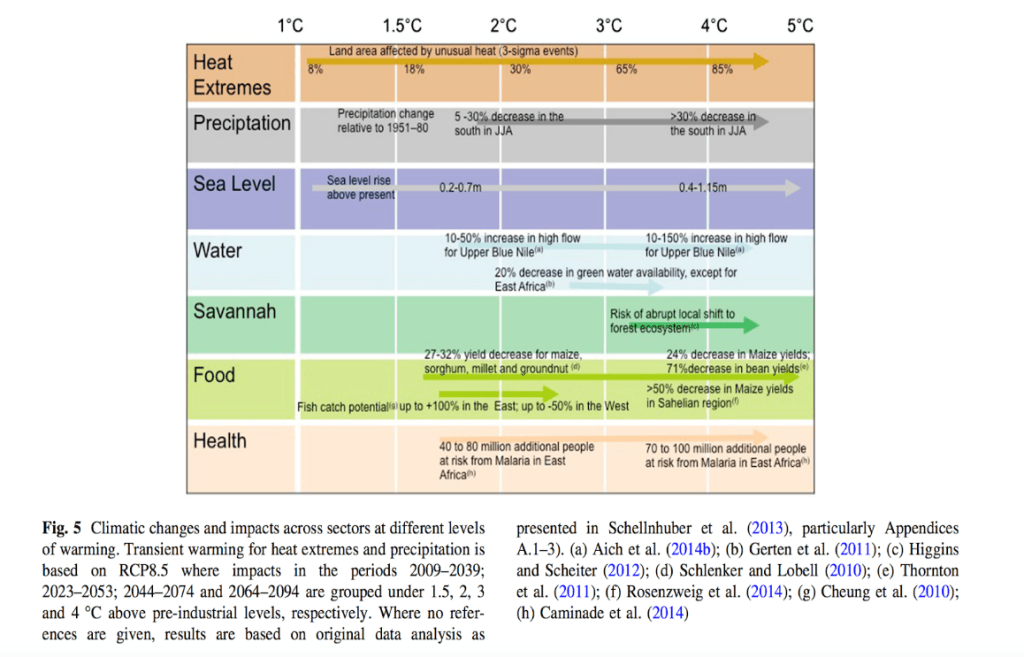

This is a fascinating read about Stalin, the ‘seemingly humane man’ and totalitarian ruler, his handling of the failures in agriculture and limited successes in manufacturing, propaganda and party purges, solidification of Party power, perspectives on capitalism, fascism, socialism, and communism, and the threats the U.S.S.R. faced from Germany, Japan, the long civil war in China, and even the small independent state of Poland. As a teacher of U.S., European, and World History, I likely spent too much time on the impact of the Great Depression and the rise of dictatorships than on the global perspective of the new Soviet empire and Japan’s vision in the Far East. The advantage of Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 is that it provides teachers with examples for decision-making lessons in every year from the first Five Year Plan until the evening of Operation Barbarossa.

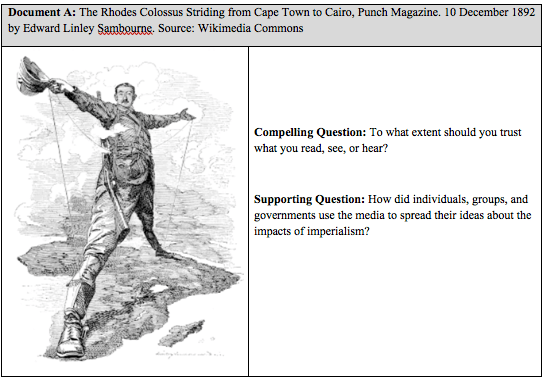

The eloquently phrased statement below by Dr. Kotkin is an argument for high school students to analyze and debate. History is about thinking and students need to investigate sources, determine their reliability, and develop their own thesis statement.

“A human being, a Communist and revolutionary a dictator encircled by enemies in a dictatorship circled by enemies, a fearsome contriver of class warfare, an embodiment of the global Communist cause and the Eurasia multinational state, a ferocious champion of Russia’s revival, Stalin did what acclaimed leaders do: he articulated and drove toward a consistent goal, in his case a powerful state backed by a unified society that eradicated capitalism and built industrial socialism. “Murderous” and “mendacious” do not begin to describe the person readers will encounter in this volume. At the same time, Stalin galvanized millions. His colossal authority was rooted in a dedicated faction, which he forged, a formidable apparatus which he built, and Marxist-Leninist ideology, which he helped synthesize. But his power was magnified many times over by ordinary people, who projected onto him their soaring ambitions for justice, peace, and abundance, as well as national greatness. Dictators who amass great power often retreat into pet pursuits, expounding intermittingly about their obsessions, paralyzing the state. But Stalin’s fixation was a socialist great power. In the years 1929-36, covered in part III, he would build that socialist great power with a first-class military. Stalin was a myth, but he proved equal to the myth.” (p. 8)

It is difficult to find humor in a book about a leader responsible for killing (and starving) millions of people but Dr. Kotkin finds the right time to tell us about the goodwill tour of Harpo Marx. In the middle of a counterrevolutionary terrorist plot against Stalin, a possible war with Japan, and FDR trying to save American capitalism from default. Harpo Marx (an American comedian) while interacting with a Soviet family in the audience has 300 table knives cascade from his magical sleeves! (p.145)

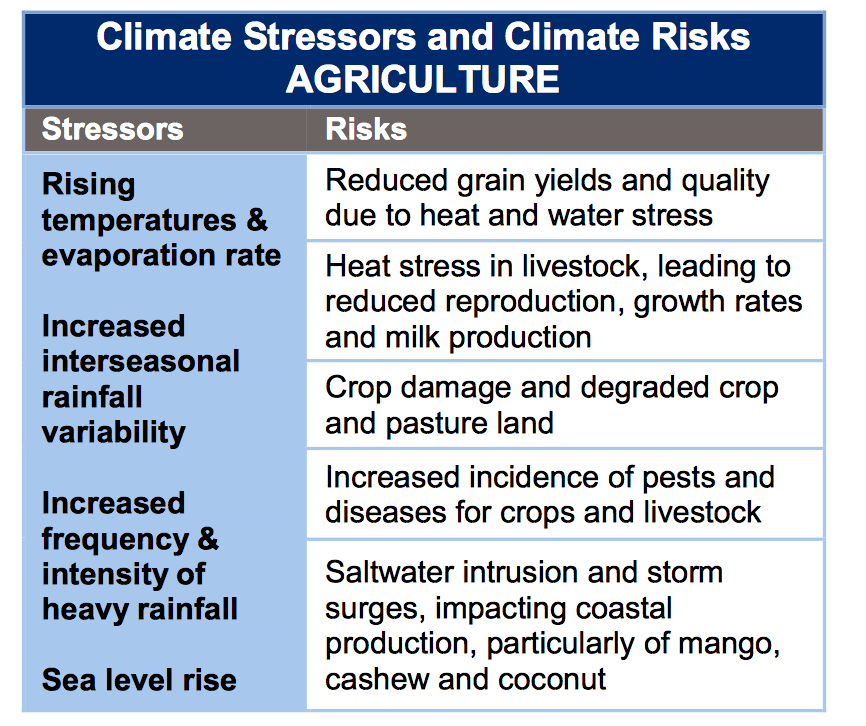

The lessons for teachers and students are enriched by the details in this book. For example, Dr. Kotkin’s analysis of the failures of the collective farms in the first four years of the First Five Year Plan provide factual data for teachers and resources for developing engaging decision-making activities for students.

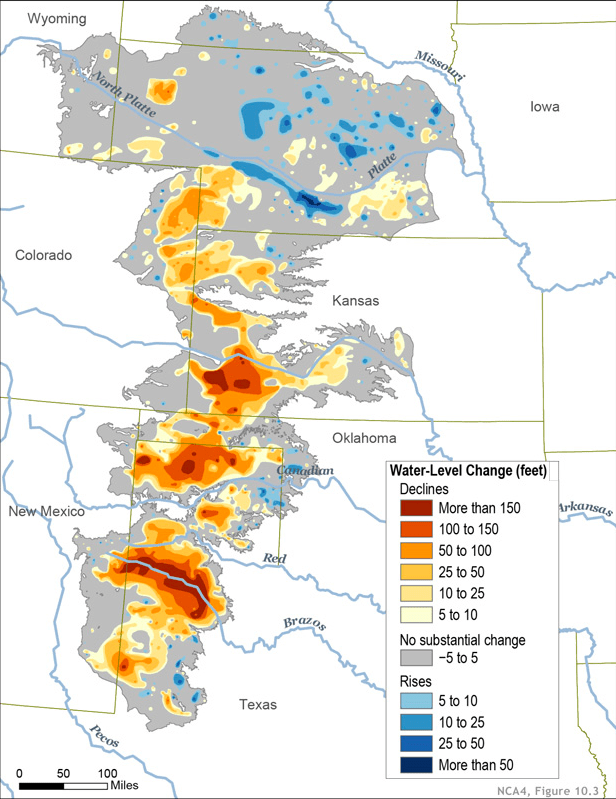

In 1929, the USSR had only 6 million out of 60 million workers employed, an unemployment rate of about 90%! Livestock and grain prices crashed as did the U.S. stock market with a 25% decline in four days of October. But in the USSR, there was a surprise harvest of 13.5 million tons. This led to forced collectivization of 80% of the private farms and the deportation of kulaks as Stalin understood the importance for agricultural security in an insecure state. Food was essential to the industrialization of the Soviet Union and for the police, army, and ordinary people. By contrast, a Soviet worker needed to labor for sixty-two hours to purchase a loaf of bread, versus seventeen minutes for an American. (p.544)

“But the dictator himself would turn out to be the grand saboteur, leading the country and his own regime into catastrophe in 1931-33, despite the intense zeal for building a new world. Rumblings within the party would surface, demanding Stalin’s removal.” (pp. 70-71)

Decision Making Activity:

Should the USSR focus on agricultural reforms before starting a program of industrial reforms? (1929-1934)

The decisions facing Stalin had to be overwhelming:

- His government faced increasing debt

- There was no organized educational system to assimilate the diverse population

- He needed to increase agricultural productivity

- The Communist Party was divided between followers of Trotsky and Stalin

- The military did not have any airplane or pilots

- Peasants were quitting the collectives by the hundreds of thousands in search of food with millions facing starvation.

- There were violent protests against local officials as one-third of the livestock perished and inflation soared.

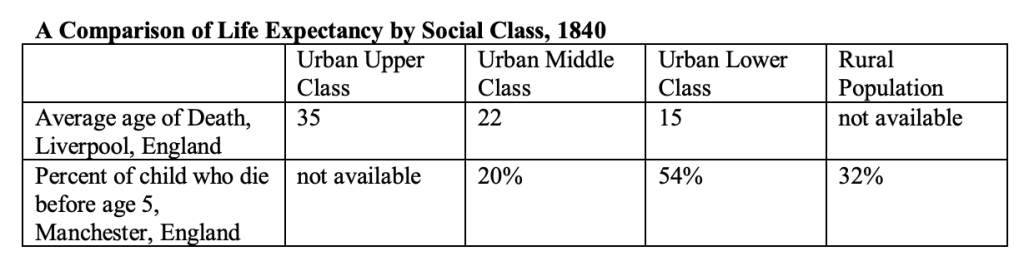

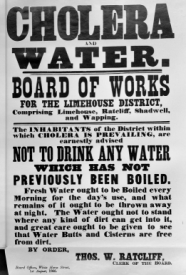

- Cholera epidemics killed about one-half million and the catastrophe in the Ukraine resulted in 3.5 million deaths, 10% of the population.

“Collectivization involved the arrest, execution, internal deportation, or incarceration of 4 to 5 million peasants, the effective enslavement of another 100 million; and the loss of tens of millions of head of livestock.” (p.131)

Decision Making Activity:

With military expansion in Japan and Germany, civil war in China, and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, should Stalin and the USSR focus on investment in military technology and building an army?

The research of Dr. Kotkin offers teachers a treasure of statistical data and insights into these critical years of Stalin’s survival. In 1931, “Japan had 250,000 troops (quarter of a million) in the Soviet Far East and Stalin had 100,000 with no fleet, storage facility or air force. At best they could transport troops on five trains a day.” (p.84). Without exports and with severe budget cuts, the USSR manufactured 2,600 tanks by the end of 1932. This was possible because Stalin secretly increased the budget for military spending from 845 rubles to 2.2 million.

The construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal (1933) was a significant investment for exporting minerals and increasing state revenue. Stalin’s infrastructure projects illustrate his understanding of the importance of industrialization. Unfortunately, the White-Sea Baltic Canal was less than fifteen feet deep in most places, limiting use to rivercraft. Stalin was said to have been disappointed finding it ‘shallow and narrow.’” In 1937, Stalin celebrated the opening of the Moscow – Volga River canal with a flotilla of forty-four ships and boasting that Moscow was linked to five seas. (White, Black, Baltic, Caspian, and Azov). Sadly, it was built with Gulag prisoners and according to Professor Kotkin, 20,000 perished. (p.404) Stalin also started The Great Fergana Canal (1939) and the Moscow subway system.

The personal accounts from diaries and interviews is a reason for teachers to read this book. For example, Stalin’s wife, Nadya, was diagnosed with angina and a defective heart valve. Although Dr. Kotkin notes that Stalin was not a playboy, as was Mussolini, Stalin’s flirtation with a 34-year-old actress after the November 7 Revolution Day parade pushed Nadya over the edge. Her body was found in a pool of blood in her room on the morning of November 9 by Karolina Til, the governess of young Svetlana, Vasily, and Artyom. The cause of death was reported as appendicitis, although it was a suicide. In the middle of this personal tragedy, 9-year-old Svetlana wrote:

“Hello, my Dear Daddy.” I received your letter and I am happy that you allowed me to stay here and wait for you….When you come, you will not recognize me. I got really tanned. Every night I hear the howling of the coyotes. I wait for you in Sochi. I kiss you.” Your Setanka.” (p.135)

Another example of the ‘seemingly human qualities’ of Josif Stalin is a description of an evening birthday celebration for Maria Svanidze, governess, Svetlana said she wanted to ride on the new Moscow metro and Stalin and the family walked on the newly opened subway. It was dark.

“Stalin ended up surrounded by well-wishers. Bodyguards and police had to bring order. The crowd smashed an enormous metal lamp. Vasily was scared for his life. Svetlana was so frightened, she stayed in the train car. We ‘were intimidated by the uninhibited ecstasy of the crowd,’ Svanidze wrote. “Josif was merry.” (p.234)

By 1933, Stalin’s fortunes were changing for the better. This is why history is often unpredictable. The collectivized fall harvests were good and the unbalanced investments of the first Five-Year Plan finally produced results. Socialism (anti-capitalism) was victorious in the countryside as well as in the city. The USSR joined the League of Nations, Harpo Marx toured the USSR, and the United States sent Ambassador William C. Bullitt to Moscow.

Decision Making Activity:

Did the United States and other countries extend diplomatic recognition to Stalin and the USSR prematurely?

Although Stalin refused to pay (or negotiate) the debt of 8 billion rubles owed to the United States since the end of World War I, he announced debt forgiveness of 10 million gold rubles to Mongolia on January 1, 1934, about 45 days after President Roosevelt agreed to formal recognition. (p.196) In 1983, the USSR repaid its debt to the United States.

The anti-terror law to protect the security of the Soviet Union led to the arrests of 6,500 people following the death of Kirov, a member of the politburo. Gulag camps and colonies together held around 1.2 million forced laborers, while exiled “kulaks” in “special settlements” numbered around 900,000. But the state media was able to boast that there were less murders in all of Soviet Union than in Chicago (p.286) For the two years 1937 and 1938, the NKVD would report 1,575,259 arrests, 87 percent of them for political offenses, and 681,692 executions.” (The number is closer to 830,000 since many more died during interrogation or transit.) (p.305)

Decision Making Activity:

Did Stalin have a reason to fear for his power or did he desire the personal power of a despot?

First, the economy between 1934-36 was relatively good as the Soviet Union escaped the tremendous debts of other countries during the Great Depression because of its limited exposure to global trade, a planned economy, and the famine ended. Stalin was suspicious of the imperialists in Britain and France, feared they would establish an anti-Soviet coalition, and attack through Eastern Europe. He needed to isolate or eliminate potential threats in the military and friends of Trotsky whose publications presented Stalin as a counter-revolutionist and one who betrayed the teachings of Marx. The Soviet empire (USSR) is a large country and assassinations are difficult to prevent.

The influence of Trotsky continued for more than a decade after his exile. Trotsky headed the Red Army until 1925 and everyone worked with him. In 1936, the NKVD arrested 212 Trotyskyites in the military, including 32 officers. (p.350) “After a decree had rescinded Trotsky’s Soviet citizenship, he had written a spirited open letter to the central executive committee of the Soviet…asserting that ‘Stalin has led us to a cul-de-sac….It is necessary, at last, to carry out Lenin’s last insistent advice: remove Stalin.” (p.372) Who could Stalin trust?

In the Middle of the Thirties the World Changed

Dr. Kotkin offers a detailed analysis of how these civil wars impacted the geopolitical balance of the new class of world leaders in Britain, France, and Germany along with the poor military record of Mussolini in Ethiopia. The Spanish and Chinese civil wars in the east and west presented challenges and opportunities for Stalin. Stalin sent 450 pilots and 297 planes, 300 cannons, 82 tanks, 400 vehicles and arms and ammunition. Stalin is the leader of the politburo but none of his top leaders had a university education.

Although these two conflicts are different, they are caused by extreme poverty and the failure of government to solve the social and economic problems. They also involved foreign interference, although in the Chinese civil war, Japan occupied significant areas of the country. Although communism was a political presence in both civil wars, it did not follow the revolutionary reforms of Lenin or Stalin. The situation in Spain likely clarified Stalin’s world view regarding his fear of conspiracies from within, the consequences of a long conflict, and the complexities of revolutionary movements.

An example of scholarship I found useful is the removal of Spain’s gold reserves, estimated at $783 million, dating back to the Aztecs and Incas. (p.343) A significant portion of this money flowed to Moscow financing the costs of new armaments. A second example is the tragic record of genocide resulting in the execution of more than 2,000 prisoners in Madrid’s jails. The human rights abuses involved the evacuation of several thousand innocent people. I was not aware of this organized attempt by Spanish communists and their Soviet advisors. (p.350) but important to classroom instruction.

The madness continued “On April 26, 1937, the German Condor Legion, assisted by Italian aircraft, attacked Guernica, the ancient capital of the Basques, at the behest of the Nationalists, aiming to sow terror in the Republic’s rear. The attack came on a Monday, market day. Not only was the civilian population of some 5,000 to 7,000 (including refugees) carpet-bombed, but as they tried to escape, they were strafed with machine guns mounted on Heinkel He-51s. Some one hundred and fifty were killed.” (p.407)

The Basques surrendered. Every effort was taken to keep Soviet involvement from the people, although Trotsky was able to influence. “He sent a telegram from Mexico to the central executive committee of the Soviet, formally the highest organ of the state, declaring that ‘Stalin’s policies are leading to a crushing defeat, both internally and externally. The only salvation is a turn in the direction of Soviet democracy, beginning with a public review of the last trials. I offer my full support in this endeavor.” (p.434)

Kristallnacht (November 9-10, 1938) is only 18 months into the future.

Some 10,000 miles away in China, the USSR is confronted with the Nanking Massacre, invasion of Mongolia, and continuing fighting between Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong. But in 1936, there was an attempted coup in Tokyo. There was much confusion regarding who in the military was behind this failed attempt because it was clearly anti-capitalist but according to Richard Sorge, the Soviet intelligence officer in the German embassy in Tokyo, it was not connected to any communist or socialist organizations. Stephen Kotkin provides substantial research on the work and missteps of Richard Sorge providing insights into how Soviet intelligence worked during the Stalin years, especially in Berlin and Tokyo. For example, Sorge photographed the full text of a secret document and sent it to a Soviet courier in Shanghai who eventually got it to Moscow stating that “should either Germany or Japan become the object of an unprovoked attack by the USSR,” each “obliges itself to take no measures that would tend to ease the situation in the USSR.” (p.356)

The Capture of Chiang Kai-shek

Stalin in the middle of his “House of Horrors” and the purges of 1937-38 discovered that history would test him as a diplomat, military strategist, and intelligence gatherer even though he had no experience in these areas. One of his first tests came to him on a cold December morning with the capture of Chiang Kai-shek, age 49, in central China. This was a turning point.

“At dawn on December 12, (1937) his scheduled day of departure, a 200- man contingent of Zhang’s personal guard stormed the walled compound. A gun battle killed many of Chiang’s bodyguards. He heard the shots, was told the attackers wore fur caps (the headgear of the Manchurian troops), crawled out a window scaled the compound’s high wall, and ran along a dry moat up a barren hill, accompanied by one bodyguard and one aide. He slipped and fell, losing his false teeth and injuring his back, and sought refuge in a cave on the snow-covered mountain. The next morning, the leader of China-shivering, toothless, barefoot, a robe over his nightshirt-was captured.” (p.360)

The detailed and descriptive connections that teachers love to share with their students, especially Zhang Xueliang’s relationship with Edda Ciano, Mussolini’s daughter and the wife of the Italian minister to China, make the story of history very realistic and relevant!

Decision Making Activity:

Should Stalin support Chiang Kai-shek or order him killed based on Shanghai Massacre in 1927 with the execution of thousands of communists?

If Chiang Kai-shek is killed, will Japan extend its presence in China?

If Chiang Kai-skek is released, will he defeat Mao Zedong, someone Stalin considered influenced by Trotsky?

In the middle of this turning point situation and the continuing fighting in Spain, Stalin’s House of Horrors executed 90 percent of his top military officers in the purges of 1937-38, about 144,000. “Throughout 1937 and 1938, there were on average nearly 2,200 arrests and more than 1,000 executions per day.” (p.347) “The terror’s scale would become crushing. More than 1 million prisoners were conveyed by overloaded rail transport in 1938 alone.” (p.438)

“Violence against the population was a hallmark of the Soviet state nearly from its inception, of course, and had reached its apogee in the collectivization-dekulakization…They would account for 1.1 million of the 1.58 million arrests in 1937-38, and 634,000 or the 682,000 executions.” (p.448). The news of Hitler’s territorial acquisition of Austria (March 12, 1938) and annexation of the Sudetenland (September 30, 1938) will occur within a few weeks and months.

For teachers looking for an inquiry or research-based lesson on Stalin’s purges, consider this statement by Dr. Kotkin: “World history had never before seen such carnage by a regime against itself, as well as its own people-not in the French Revolution, not under Italian fascism or Nazism.” (p. 488) The madness was similar to the spread of a virus with one arrest infecting others. It only required an executive order (or consider it a ‘prescription’) to cure the infection of suspicion.

On the Eve of Destruction

By 1938, Stalin had 11 years of experience as the absolute leader of the Soviet government. During these 11 years he had changed the domestic policy of the Soviet Union. In 1939, Time Magazine honored him as Man of the Year for his accomplishments. The issue characterized Stalin as a man of peace by comparing him to Mussolini, Hitler, and Roosevelt. He was also Man of the Year in 1943. Your students will find this interesting!

This is the year Stalin celebrated his 60th birthday (Dec. 18, 1878) and it is also the time when the world changed. Stalin would begin a journey where he lacked experience and because he arrested and executed 90% of his top military leaders resulting in no one to go to for diplomatic or military advice. Stalin was left with Peter the Great and the realpolitik of Bismarck for the play book on how to handle Mussolini, Hitler, and Chamberlain, Churchill, and Roosevelt.

“Germany’s mobilization was so sudden, ordered by the Fuhrer at 7:00 p.m. on March 10, 1938…Events moved very rapidly. On March 12, a different Habsburg successor state vanished when the Wehrmacht, unopposed, seized Austria, a country of 7 million predominantly German speakers. It was the first time since the Great War that a German army had crossed the state frontier for purposes of conquest, and, in and of itself, it constituted an event of perhaps greater import than the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which helped spark the Great War mobilizations of 1914.” (pp.558-559)

The Soviet Union had a border on the west of almost 2,000 miles and a 2,600-mile border in the east with China. The Soviet Union had an inefficient transcontinental railroad, a small air force, an army that did not understand the Russian language, 6,000 nautical miles of coastline, seaports that were easily blocked by mines or ice, and a small navy! Stalin understood the fate of the Soviet Union as Japan had 300,000 forces in Manchukuo and 1,000,000 in northern China and controlled Peking, Tientsin, and Shanghai in less time than it took me to write this review! (p. 457)

The brilliance of this book is in the details and interesting personal stories. In the context of writing about Stalin’s introduction to foreign policy, Dr. Kotkin describes the life of Benito Mussolini in vivid detail with comparisons to Stalin and Hitler.

“On a typical day in 1938, spent an hour or two every afternoon in the downstairs private apartment in the Palazzo Venezia of Claretta Petacci, whom he called little Walewska, after Napoleon’s mistress. The duce would have sex, nap, listen to music on the radio, eat some fruit, reminisce about his wild youth, complain about all the women vying for his attention (including his wife), and have Walewska dress him. Before and after his daily trysts…the duce would call Claretta a dozen times to report his travails and his ulcer.” (p.525)

“Stalin’s world was nothing like the virile Italian’s. Women in his life remained very few. He still did not keep a harem, despite ample opportunities…..If Stalin had a mistress, she may have been a Georgian aviator, Rusudan Pachkoriya, a beauty some twenty years his junior, whom he observed at an exhibition at Tushino airfield.” (p.525)

Decision Making Activity:

Faced with these rapidly changing events as a result of the decisions of Japan and Germany, what should Stalin do?

- Seek an alliance with another state?

- Change the budget priorities from rebuilding the infrastructure of the Soviet Union to military spending?

- Begin a campaign of disinformation to the Soviet people about the international threats?

- Double down on finding Trotsky and have him executed to avoid an internal threat of revolution?

- Name a possible successor, should something happen to Stalin.

Throughout the book there are provocative claims that should challenge AP European History students to think: For example: “So that was it: Germany foaming at the mouth with anti-Communism and ant-Slav racism, and now armed to the teeth; Britain cautious and aloof in the face of another continental war; and France even more exposed than Britain, yet deferring to London, and wary of its nominal ally, the USSR. Stalin was devastating his own country with mass murders and bald-faced mendacities, but the despot faced a genuine security impasse: German aggression and buck-passing by great powers-himself included.” (p.593)

Investigate or Debate:

Stalin passed the supreme test of state leadership in 1939.

Stalin failed the supreme test of state leadership in 1939.

The first argument should investigate the evidence regarding the risks and rewards of selling resources to Hitler and Germany. Did this enable Hitler to become stronger or did it enable the Soviet Union to gain trade revenue to rebuild its military and infrastructure? The lessons of geography, imperialism, alliances, and military preparation from 1914 are complex and difficult for a state leader to master.

Hitler needed the resources of oil, steel and grain and the Ukraine in the Soviet Union was the treasure. Poland understood Hitler’s motives and knew that an attack on the Soviet Union by Japan would likely extend their short-lived independence. Dating back to the end of World War I, Polish forces still occupied the western Ukraine along with German troops. If the Blitzkrieg was to take place in six months, Germany needed these troops. Meanwhile, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) desired independence and Pavel Sudoplatov, from the Soviet Union, blew up Yevhen Konovalets, the OUN leader, with a concealed time bomb in a box of chocolates in a Rotterdam restaurant. In two years, he will get to Trotsky. (p.596)

Students should also use the analysis and end notes in this book to determine if Stalin made the right decisions regarding who he trusted. Could he trust President Roosevelt? Neville Chamberlain, Adolph Hitler? Richard Sorge? Edouard Daladier? Stalin: Waiting for Hitler. 1929-1941 is a debater’s dream with 160 pages of notes and a Bibliography of almost 50 pages in size 3 font!

The year, 1939 marked the opening of the World’s Fair in New York City with thousands of visitors; it is also the year when the Nazi’s smashed Jewish owned stores, businesses, and synagogues in November 9-10, killing at least 100 innocent Jewish people. Was Stalin the best person to stop Hitler or did his silence empower him? There is evidence in the book to support both arguments.

These are challenging events for students to grasp and some of the best lessons for historical inquiry and “What If” scenarios. To emphasize the complexities of role-playing history in real time, consider that Lithuania relinquishes the deep-water Baltic port of Memi (Klaipėda) to Hitler’s ultimatum and Romanian businesses negotiate partnerships with Germany providing access to the unlimited oil supplies in the Ploiesti region. (p.613). During these fast-moving events, Stalin promoted Nikita Khrushchev to the politburo (p.605), Alexi Kosygin as commissioner of textile production, and Leonid Brezhnev to party boss in his region. (p.603).

“Khrushchev had to authorize arrests, and, in connection with the onset of ‘mass operations,’ he’d had to submit a list of ‘criminal and kulak elements,’ which in his case carried an expansive 41,305 names; he marked 8,500 of them ‘first category’ (execution). At least 160,000 victims in Moscow and Ukraine, would be arrested under Khrushchev during the terror.” (p.520)

We are now on a countdown of less than six months to Blitzkrieg and two years to Operation Barbarossa.

Historical Claim: “The Fuhrer really be stopped or even deflected?” (p.641)

The arguments below are a sample of the resources in the narrative of Dr. Kotkin’s book.

Hitler’s rearmament starved Germany of resources. This limited Hitler’s ability to fight in a long war and it negatively affected the German people. Hitler could not risk a war with the Soviet Union if his intention was to dominate western Europe.

Three weeks before the planned attack on Poland, Stalin entered into official talks with Germany on August 11, 1939 and by August 20, an economic agreement was finalized.

Mussolini did not sign the Pact of Steel until August 25, less than one week before the invasion.

France had 110 divisions compared to Germany’s 30, with only 2 considered to be combat ready. (p. 680)

The invasion of Poland was planned for August 25 but Hitler got cold feet after he gave the final order. Would Hitler risk a world war over Poland, which he could also obtain by negotiation or ultimatum?

Italy also desperately needed resources. Mussolini told Hitler he needed 7 million tons of gasoline, 6 million tons of coal, and 2 million tons of steel.

The history of the world might have taken a different course. For example, one week before the blitzkrieg of Poland, the Soviet air force fired on Hitler’s personal Condor by mistake when it was flying to Moscow with Joachim von Ribbentrop aboard to sign the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact. They missed. (See another example on page 10 about Rudolph Hess’ plane crash in Scotland and the failed assassination plot against Adolph Hitler in Munich)

On September 1, 1939 the blitzkrieg began. “The Germans in Poland, by contrast, had lost between 11,000 and 13,000 killed. At least 70,000 Poles were killed and nearly 700,000 taken prisoner. The atrocities would continue long after the main combat was over. More than a million Poles would be forced to work as slaves in Germany.” (p.688) The day before Hitler gave the order to double the production of the new long-range ‘wonder bomber”, the Ju88 for use against Britain.

Frozen in Finland

On the afternoon of November 26, 1939, five shells and two grenades were fired on Soviet positions at the border, killing four and wounding nine. “An investigation by the Finns indicated that the shots had emanated from the Soviet side. They were right. “The Finns maintained that Soviet troops had not been in range of Finnish batteries, so they could not have been killed by Finnish fire, and suggested a mutual frontier troop withdrawal.” (p.722) The Soviets never issued a formal declaration of war. Hitler would now see the strength of the Soviet armor, even though the Finns were still using 20-year-old tanks from World War I. (p.726)

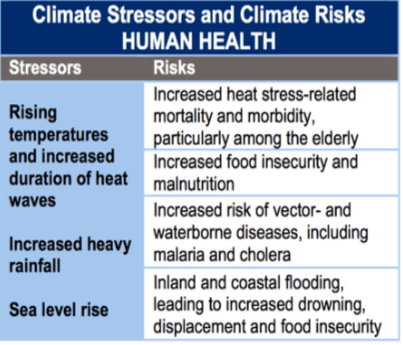

The Winter War of 1940-41 is a significant event in the timeline of World War II. Unfortunately, it is one that most teachers and students overlook because of the fast-moving events between Blitzkrieg and Barbarossa. The Red Army suffered frostbite in the -45-degree weather, guerrilla attacks with flammable liquids stuffed in bottles and ignited by hand-lit wicks (Molotov cocktails), and stuck on the ice of frozen lakes. (p.727) Would the history of the 20th century be different if Stalin defeated Finland in a matter of weeks and Hitler and Mussolini saw the strength of the Soviet military? Would the history of Europe be different if Finland maintained its independence? Students need to investigate what went wrong with the strategy of the Soviet Union to control Finland and the Baltic Sea. Winston Churchill had limited knowledge of Stalin and the Soviet Union when he made the statement below. In fact, he only gained popularity as few months before as a result of Hitler’s Lebensraum. Given this understanding, how accurate is his statement below?

Winston Churchill stated it clearly on January 20, 1940: “The service rendered by Finland to mankind is magnificent. They have exposed, for all the world to see, the military incapacity of the Red Army and of the Red Air Force. Many illusions about Soviet Russia have been dispelled in these few fierce weeks of fighting in the Arctic Circle.” (p.740)

“Finland paid a heavy price for the avoidable war. Nearly 400,000 Finns (mostly small farmers) upward to 12 percent of its population – voluntarily fled the newly annexed Soviet territories for rump Finland, leaving homes and many possessions behind, and denying the NKVD victims to arrest. Finland suffered at least 26,662 killed and missing, 43,357 wounded, and 847 captured by the Soviets.” (p.748) Finland lost its independence to Nazi Germany.

“Still the Soviets lost an astonishing 131,476 dead and missing; at least 264,908 more were wounded or fell to illness, including the frostbitten, who lost fingers, toes, ears. Total Soviet losses neared 400,000 casualties, out of perhaps 1 million men mobilized – almost 4,000 casualties per day.” (p.748) On March 5, 1940, Stalin approved the execution of 21,857 captured or arrested Polish officers.

Another “What if” situation, similar to the shooting down of the plane taking Ribbentrop to Moscow in August, occurred only two months after the blitzkrieg and during this winter war in Finland when “Georg Elser planted a bomb in one of the columns right behind the podium of the Munich Beer Hall where Hitler was scheduled to speak on November 8, 1939. It was a year-long plot planned by Elser. But fog forced Hitler to travel from Berlin to Munich by a regularly scheduled train. He began his speech early and left ten minutes before the explosion. Eight were killed and 60 were wounded.” (p.700)

If you enjoy these unexpected stories, Dr. Kotkin offers another bizarre account, involving Rudolph Hess, which took place during the Attack on Britain in 1940.

“On May 13, although details were scarce, he (Stalin) learned of a sensation reported out of Berlin the previous night: Rudolf Hess, deputy to the Fuhrer within the Nazi party, had flown to Britain. “Late on May 10, a date chosen on astrological grounds, in a daring, skillful maneuver, he piloted a Messerschmitt Bf-110 bomber across the North Sea toward Britain, some 900 miles, and, in the dark, parachuted into Scotland. His pockets were filled with abundant pills and potions, including opium alkaloids, aspirin, atropine, methamphetamines, barbiturates, caffeine tablets, laxatives, and an elixir from a Tibetan lamasery. He was also carrying a flight map, photos of himself and his son, and the business cards of two German acquaintances, but no identification. Initially, he gave a false name to the Scottish plowman on whose territory he landed; soon members of the local home Guard appeared (with whisky on their breath). The British were not expecting Hess; no secure corridor had been set up. Hess was among the small circle in the know about the firmness of Hitler’s intentions to invade the USSR.” “Hitler stated that Hess had acted without his knowledge, and called him a ‘victim of delusions.’” (pp.866,67)

On the eve of the Battle of Britain and Fall of France, Dr. Kotkin offers a view of the Soviet home front. Stalin, a leader with no military experience, worked aggressively since 1936 to build the largest army in the world. Considering the debt of the Soviet Union during the 1930s, what price did the people pay?

(I apologize that I cannot verify the accuracy of the data below but offer it for the purpose of discussion regarding the changes occurring in the Second Five Year Plan with an emphasis on industrial production.)

source: (R.W. Davies, Soviet economic development from Lenin to Khrushchev, 40.)

“The Red Army was expanding toward 4 million men (as compared with just 1 million in 1934). Some 11,000 of the 33,000 officers discharged during the terror had been reinstated. Consumer shortages had been worsening since 1938. At the same time, alcohol production reached 250 million gallons, up from 96.5 million gallons in 1932. By 1940, the Soviet Union had more shops selling alcohol than selling meat, vegetables, and fruit combined.” (p.781)

Britain, France and the Fate of the Soviet Union

As the war intensified in 1940 with the attack on France, Stalin was forced to reassess what was developing. He knew, or thought he knew, that the Soviet Union would be safe from German invasion for resources as long as Hitler was fighting in western Europe. But the battle in France began on Mother’s Day and ended shortly after Father’s Day. (May 10 – June 25) The French air force was no match for the Luftwaffe and the French had done little regarding the installation of antitank obstacles and bunkers in the Ardennes. (p.766) “The French lost 124,000 killed and 200,000 wounded, while 1.5 million western troops were taken prisoner; German casualties were fewer than 50,000 dead and wounded.” (pp.767)

What did Stalin think? Stalin depended on the French military and Germany fighting in western Europe. Did Stalin connect the missing pieces of the puzzle regarding the importance of Russian oil and supplies to Germany’s power? Between July 10 and the end of October 1940, Germany bombed Britain. The British lost 915 planes but the Germans lost 1,733 planes, almost double the number. (p.794)

The only silver lining in the storm clouds over western Europe for Stalin was on August 20, 1940. After five years of failed attempts to get Leon Trotsky, including the discharge of 200 bullets into his bedroom on May 27, 1940, Ramon Mercader managed to smash a pick into his head. Nearly 250,000 watched the funeral possession in Mexico City. For Stalin, the revolution was now complete!

Decision-Making Activity:

Meeting of the politburo, January 1941. Have your students prepare a report to Stalin about the best defensive strategy for the Soviet Union for 1941. The members of the politburo have just received an intelligence report from Richard Sorge in the Germany embassy in Tokyo regarding an expected target date for an attack on the Soviet Union on May 15, 1941.

Here are the facts: (pp.819-830)

- The Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact is no longer certain.

- The Winter War against Finland was a military disappointment.

- Germany controls a significant part of France, including Paris.

- It is a risk for Germany to fight a two-front war against Britain and the Soviet Union at the same time.

- It is estimated that Germany has 76 divisions in the former Poland and 17 in Romania, with an estimate of 90-100 in western Europe.

- The Soviet Union is spending 32 percent of its budget on the military and has the largest army in the world at 5.3 million. Germany spends about 20% of its budget on the military.

- Germany and Italy need supplies of oil, steel, and grain.

- The USSR promised to ship Germany 2.5 million tons of grain, some from strategic reserves, and 1 million tons of oil by August 1941, in return for machine tools and arms-manufacturing equipment.

- The Soviet border from the White Sea to the Black Sea is 2,500 miles and vulnerable to attack at any point.

- Franklin Roosevelt will be inaugurated as President of the United States on January 20, 1941 and is committed to supplying Britain with aid as an ‘arsenal for democracy’.

- The war in the Balkans began on October 28, 1940 and Italy’s offensive is moving slowly.

- The United States broke the Japanese intelligence code, should Stalin explore help from the United States?

- The Soviet Union needs to expand the trans-Siberian Railroad.

- Stalin does not believe Hitler and the German army are invincible and they can be defeated.

- The NKVD captured 66 German spy handlers and 1,596 German agents, including 1,338 in western Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltics.

Here are the Unknown Factors: “Hitler estimated it would take four months to defeat USSR” (p.882).

- Would a blitzkrieg attack on German forces along the Soviet frontier deliver a knockout blow?

- Will a surprise Soviet attack on Germany move Britain and Germany to negotiate a settlement.

- Should the Soviet Union move back 100 miles to draw the Germany army into Soviet territory and they encircle them?

- How will Churchill and Britain react to a German attack on the Soviet Union? How will FDR and the United states react?

- Are the Germans secretly moving their army on trains from western Europe to the Soviet frontier?

- If Germany intervenes in the Balkans will this enable them to invade the Soviet Union?

- Is Richard Sorge a double agent that should not be trusted?

- What are Hitler’s plans?

- Will a Soviet campaign of disinformation be effective?

- Will an accidental war break out with an unknown incident at the border?

This is a fascinating book to read and I have decided to leave the creative and carefully researched Conclusion that Stephen Kotkin has written as a surprise. It is perhaps the best ending of a book or documentary that I have read. I cannot wait to read the third volume of the attack on the Soviet Union and the aftermath.

Regarding my opening statement: “The opening sentence, the thesis statement, by Dr. Kotkin is capitalized: “JOSIF STALIN WAS A HUMAN BEING.” Perhaps the argument is correct. Stalin loved his mother, was the father of three children, and witnessed the unfortunate early deaths of his two wives, Kato Svanidze, at age 22 of illness and Nadezhda Alliluyeva, of suicide at age 31. Even though in my reading of this book, I understood Stalin as stoic and emotionally removed from his executive orders leading to the imprisonment and execution of millions, I kept thinking that he lived with feelings, remorse, and personal guilt. I may never know but I can speculate.

Personal Note:

A thousand-page book is not a quick read. My five grandchildren were impressed with the size of the book and why the grandfather would read about a man who did terrible things. I documented my quotations carefully with the intention that teachers might use them as a reference guide should they purchased this book. I am happy to give them to you upon request.

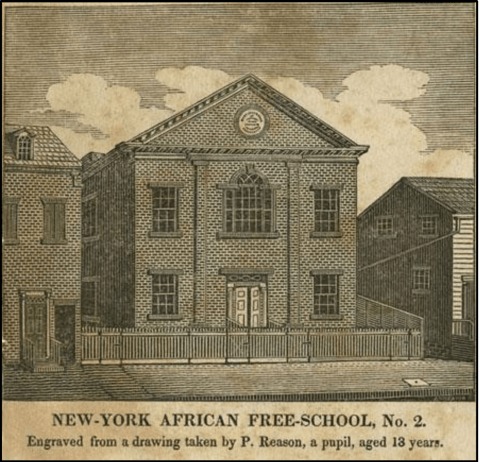

My first course in Russian history was in 1967. It was a wonderful introduction to Russian culture, geography, socialism, communism, and 20th century foreign policy. As a teacher, I read Professor Kotkin’s books and attended several of his lectures, I never had the luxury of taking a second college course. As a first-year teacher in New York City in 1969, I made arrangements for Alexander Kerensky to speak with my students. Unfortunately, he broke his arm and was hospitalized in April and passed in June 1970. In the 1960s, Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana, moved to Long Island and later to Pennington, NJ and Princeton. Although I never had an opportunity to see her, I was mesmerized by her decision to come to the United states so soon after the Cuban Missile Crisis. In 1999, I had the pleasure of dinner with Sergei Khrushchev, the son of Nikita Khrushchev.

The NJCSS also advertises the Prakhin International Literary Award on Nazi Holocaust & Stalinist Repression. Information is on our website, www.njcss.org