Addressing Israel, Palestine, Gaza, Hamas, Islamophobia, and Antisemitism in the High School Curriculum

Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School, Brooklyn, NY and the Bridging Cultures Group

Many teachers are nervous about discussing the Middle East crisis in class. In a highly heated atmosphere, they are unsure about how to approach the controversies, what is grade appropriate, and they fear criticism no matter what they do or say. The ongoing war launched by Israel on Gaza in response to an attack by Hamas is a topic that should be discussed in classes. Students across the age span have already been exposed to information and misinformation on television broadcasts, through

social media, and at family gatherings. Some have participated in marches or rallies. According to the New York State Social Studies Framework, students are expected to begin examining current events starting in third grade where they learn to distinguish between long-term and immediate causes and the effects of an event on their own lives, current events,

and history.

In response to teacher and student questions, teachers and administrators at Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School in Brooklyn partnered with Bridging Cultures Group to develop material for

integrating lessons on Israel, Gaza, Hamas, Islam, and antisemitism into the curriculum. Study of conflicts in the Middle East are part of the 8th, 10th, and 11th grade social studies curriculum. According to the Social Studies Framework, in 8th grade United States history students should learn that “The period after World War II has been characterized by an ideological and political struggle, first between the United States and communism during the Cold War, then between the United States and forces of instability in the Middle East. Increased economic interdependence and competition, as well as environmental concerns, are challenges faced by the United States.”

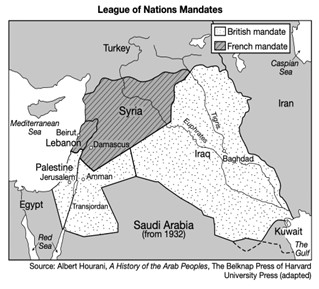

In New York, in 10th grade students learn how “Nationalism in the Middle East was often influenced by factors such as religious beliefs and secularism.” Students are expected to “investigate Zionism, the mandates created at the end of World War I, and Arab nationalism” and “the creation of the

State of Israel and the Arab-Israeli conflict.”

In 11th grade they examine how “American strategic interests in the Middle East grew with the Cold War, the creation of the State of Israel, and the increased United States dependence on Middle Eastern oil. The continuing nature of the Arab-Israeli dispute has helped to define the contours of American policy in the Middle East.” As part of this unit, “Students will examine United States foreign policy toward the Middle East, including the recognition of and support for the State of Israel, the Camp David Accords, and the interaction with radical groups in the region.”

In 12th grade, New York State students study the organization and role of the United States government. There are no content specifications, and the course is expected to “adapt to present local, national, and global circumstances, allowing teachers to select flexibly from current events to illuminate key ideas and conceptual understandings.”

A teacher’s responsibility is to find or put together documents from different perspectives that students can evaluate together, to ask probing questions and develop an informed opinion on topics

in a safe classroom environment.

These are compelling questions that can be addressed in high school Global history classrooms.

- What was the origin of Zionism?

- How did World War I impact Palestine?

- How did the Holocaust and World War II shape the future of Israel and Palestine?

- What was the outcome of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War?

- What was the origin of the PLO?

- What were the results of the Six-Day and Yom Kippur wars?

- Why did Palestinians launch an Intifada?

- What is the origin of Hamas?

- Why is it difficult to resolve conflicts between Israel and Palestine?

- Why has the war in Gaza drawn international attention

- These are compelling questions that can be addressed in high school United States history

classrooms. - How did Middle east conflicts impact on the domestic front?

- How did U.S. support for Israel lead to an oil embargo?

- What was the impact of the oil embargo on the American people?

- How has the United States tried to resolve Middle East conflicts?

- The material included in this package are only suggestions. Teachers should adapt lesson ideas and

documents to make them appropriate for their students. Some of the material presented in this package is prepared using different formats. - Aim: Why is there a conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians?

Do Now: Cartoon analysis.

- See: What do you see happening in the cartoon?

- Think: Based on your observations, what can you infer about the conflict between Palestine and Israel?

- Wonder: Write down questions you have about the conflict between Israel and Palestine.

- Historical thinking skills practice: Using the google slides and the video

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bno1m1zhIWs), to explain the historical context of the Israeli –

Palestinian conflict. Use the three images below and answer the questions following “Review of Key Ideas.”

Review of key ideas

I: The Arab/Palestinian -Israeli Conflict: 1948- present day Key vocabulary: Zionism – the belief that Jews should have their own homeland; Zionism strengthens after the Holocaust.

II: Balfour Declaration: The British set up Palestine as the Jewish homeland.

III: Mandate Border 1920: Set up by the British; 90% of Palestine inhabited by Arabs.

IV: UN Resolution 1947: UN votes to divide Palestine into two countries. Jews agree to plan, Arabs do not. May 14, 1948, the state of Israel was born.

V. Since the establishment of Israel, there has been conflict between Israelis and the Palestinians as well as neighboring Arab countries.

Questions

- How did this conflict start?

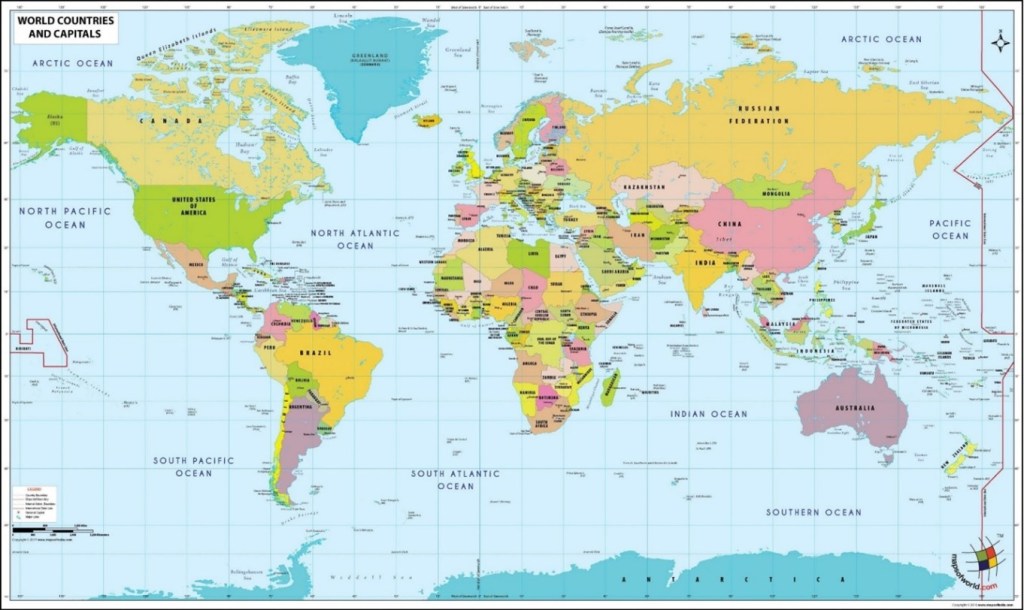

- Where is the conflict happening?

- Who is fighting?

Historical thinking skills practice: Identify viewpoints and explain how they are similar and different.

Exit Ticket: In your opinion, will the conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians ever end? Is peace possible? Why or why not?

AIM: What were the historical circumstances that led to conflicts between Jews and Palestinians?

Lesson Objective: Contextualize the origins of the Israel and Palestinian series of conflicts.

ACTIVITY 1: DO NOW – STUDENT CHOICE

Directions: Choose an option below. You don’t have to do both.

OPTION A: The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I in which the Government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif of Mecca launching the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The correspondence had a significant influence on Middle Eastern history during and after the war; a dispute over Palestine continued thereafter.

OPTION A QUESTION: What was the purpose of the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence?

OPTION B: The Sykes-Picot Agreement

Sykes-Picot Agreement, (May 1916), secret convention made during World War I between Great Britain and France, with the assent of imperial Russia, for the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire. The agreement led to the division of Turkish-held Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine into various French- and British administered areas. Negotiations were begun in November 1915, and the final agreement took its name from the chief negotiators from Britain and France, Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot. Sergey Dimitriyevich Sazonov was also present to represent Russia, the third member of the Triple Entente.

OPTION B QUESTION: Who controlled Palestine after the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in May 1916?

ACTIVITY 2: THINK/PAIR/SHARE

Directions: Read the question in the box below. Think about it, talk to your neighbor about it, share it out.

According to what we went over in the do now, after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, who should have control of Palestine? Use evidence from the reading to support your answer.

ACTIVITY 3: CRQ PRACTICE

Directions: Analyze the documents below and answer the questions that follow.

DOCUMENT 1: Zionism

Zionism is a Jewish nationalist movement that has had as its goal the creation and support of a Jewish national state in Palestine, the ancient homeland of the Jews. Below are quotes from Zionist Theodor Herzl.

“Oppression and persecution cannot exterminate us. No nation on earth has endured such struggles and sufferings as we have . . . Palestine is our unforgettable historic homeland. . . Let me repeat

once more my opening words: The Jews who will it shall achieve their State. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and in our own homes peacefully die. The world will be liberated by our

freedom, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness. And whatever we attempt there for our

own benefit will redound mightily and beneficially to the good of all mankind.” – Theodore Herzl,

February 1896

1.What is the historical context to the ideas shown in Document 1?

DOCUMENT 2: Balfour Declaration

Balfour Declaration, (November 2, 1917), statement of British support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” It was made in a letter from Arthur James Balfour, the British foreign secretary, to Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd.

Baron Rothschild, a leader of the Anglo-Jewish community.

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” – Arthur James Balfour, British Foreign Secretary

- What is the primary purpose of the Balfour Declaration?

- Identify a cause-and-effect relationship between the events shown in Documents 1 and 2.

- ACTIVITY 4: THINK/PAIR/SHARE

Directions: Read the question in the box below, think about it, talk to your neighbor about it, share it out.

After reading about Zionism and the Balfour Declaration, why do you think Jewish people were

granted a national home in Palestine? Use evidence from the reading to support your answer. - ACTIVITY 5: EXIT ASSESSMENT

Directions: Answer the following exit question in the box below.

What were the historical circumstances that led to conflicts between Jews and Palestinians?

AIM: How did World War II impact on Israel and Palestine? - ACTIVITY 1: DO NOW – STUDENT CHOICE

Directions: Choose an option below. You don’t have to do both.

OPTION A

- What is the historical context/circumstances to the events shown in Option A?

OPTION B

Source: A Survey of Palestine: Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the

Information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. Vol. 1. Palestine

- What trends do you notice according to the chart about Jewish immigration to Palestine in the mid 1930s?

ACTIVITY 2: WORD/SENTENCE/MAIN IDEA

Directions: Read the text quietly. Then go back and read the text again. In the box on the other side,

identify a key word, sentence, and main idea of the reading. We will have a group discussion after.

Beginning in 1929, Arabs and Jews openly fought in Palestine, and Britain attempted to limit Jewish

immigration as a means of appeasing the Arabs. As a result of the Holocaust in Europe, many Jews

illegally entered Palestine during World War II. Jewish groups employed terrorism against British

forces in Palestine, which they thought had betrayed the Zionist cause. At the end of World War II, in

1945, the United States took up the Zionist cause. Britain, unable to find a practical solution, referred

the problem to the United Nations, which in November 1947 voted to partition Palestine. The Jews

were to possess more than half of Palestine, although they made up less than half of Palestine’s

population. The Palestinian Arabs, aided by volunteers from other countries, fought the Zionist forces, but by May 14, 1948, the Jews had secured full control of their U.N.-allocated share of Palestine and also some Arab territory. On May 14, Britain withdrew with the expiration of its mandate, and the State of Israel was proclaimed.

Key Word: Key Sentence: Main Idea:

ACTIVITY 3: VIDEO ANALYSIS

Directions: Watch the video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iRYZjOuUnlU) and summarize the

events of the Israel/Palestine conflict.

ACTIVITY 4: HISTORICAL THINKING SKILLS PRACTICE

Directions: Look at the map below and answer the historical thinking questions. Examine the questions from the 2023 Global History Regents and see why the New York Post reported some Jewish leaders (https://nypost.com/2023/01/31/new-york-regents-exam-blasted-for-loaded-questions-about-israel/) saw this as a biased source.

2023 Global History Regents Questions

1.Which historical event most directly influenced the development of the 1947 plan shown on Map A?

(1) Russian pogroms

(2) the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

(3) Paris Peace Conference

(4) the Holocaust

2.Which group benefited the most from the changes shown on these maps?

(1) Zionists and Jewish immigrants

(2) the government of Jordan

(3) Palestinian nationalists

(4) the citizens of Lebanon

Historical Thinking Questions

- What is the historical context/circumstances that led to the maps shown?

- What is the primary purpose of maps A, B, and C?

- Is there a potential bias in the maps? yes/no explain why.

Biased? In your opinion, are these questions biased? Explain.

AIM: Can a two-state solution work between Israel and Palestine?

Lesson Objective: Contextualize the current situation between Israel and Palestine.

ACTIVITY 1: DO NOW – STUDENT CHOICE

Directions: Choose an option below. You don’t have to do both.

OPTION A: What is the cartoonist’s point of view regarding Hamas?

OPTION B: What is the cartoonist’ point of view regarding Israel?

ACTIVITY 2: WORD/SENTENCE/MAIN IDEA

Directions: Read the text quietly. Then go back and read the text again. In the box on the other side,

identify a key word, sentence, AND main idea of the reading. We will have a group discussion after.

Hamas is a Palestinian militant group that governs the Gaza Strip. It was founded in 1987 during the

First Intifada, aiming to establish a Palestinian state and to oppose the existence of Israel. On the other hand, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, opposes a Palestinian state hood. This two-state solution refers to the proposal of creating separate Israeli and Palestinian states coexisting peacefully alongside each other. Various attempts to resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict have been made over the years, including the Oslo Accords, Camp David Summit, and the Annapolis Conference, among others. However, sustained peace has remained elusive, with factors such as ongoing violence, settlement expansions, and political disputes hindering progress towards a lasting resolution.

Key Word: Key sentence: Main Idea:

ACTIVITY 3: VIDEO ANALYSIS

Directions: Watch the video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2PguJV7l24&t=110s).

- What claims are presented in the video?

- What evidence is presented to support the claims?

- Do you agree with the claims made in the video? Explain.

- New York State Social Studies Standards:

Overall: Common Core Learning Standards:

Reading:

Cite specific text evidence from the text

Provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text

Determine whether earlier events caused later ones or simply preceded them

Determine the meaning of words as they are used in a text

Writing:

Write explanatory text with relevant and sufficient facts, concrete details, and appropriate examples

Use precise language and domain specific vocabulary

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience

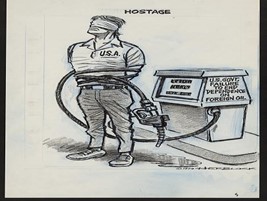

Procedure: - Do Now: Students will be provided with a choice of either using the photographs or the political cartoons to answer the questions.

Questions to consider:

1.How were Americans impacted by oil?

2. Even though these cartoons and photographs are from the 1970’s are there any connections that you can make to current day in the United States?

ACTIVITY 4: PRIMARY SOURCE VIDEO ANALYSIS

Directions: Watch the video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbObjWkKw_8).

- What claims are made by Senator Schumer?

- What evidence does he present to support the claims?

- Do you agree with the claims made by Senator Schumer? Explain.

ACTIVITY 5: PRIMARY SOURCE VIDEO ANALYSIS

Directions: Watch the video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jsxI0QjxJs8).

- What claims are made by Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu?

- What evidence does he present to support the claims?

- Do you agree with the claims made by Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu? Explain.

Exit Ticket: In your opinion, is a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine possible or likely at this time? Explain.

Lesson: 1970s Presidents/policies / U.S. History 11th Grade

Aim: How did various foreign policy decisions impact the United States during the 1970’s?

Objective: Students will learn about the OPEC oil embargo and the Camp David Accords during the

various presidencies of the 1970’s by completing an SEQ 1 task. - Mini-Lesson

a. Essential vocabulary

b. Background information. Students will engage in a turn and talk with one another to note the

relations between the US and the Middle East during this time. - Activity #1 Students read/annotate text and to evaluate the documents concerning oil during the 1970’s

Vocabulary: Camp David Accords: Peace Treaty signed between Israel and Egypt in 1979 that took

place at Camp David with President Carter.

Directions: Do a close read of the following text passage. Annotate using note-taking symbols.

Reading: 1970’s U.S.

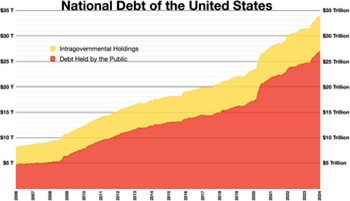

The 1970’s was a decade of when the various conflicts concerning the Middle East. This began on October 19, 1973, when President Nixon requested Congress authorize $2.2 billion in emergency aid to Israel. Israel was attacked by its Arab neighbors in what came to be known as the Yom Kippur War because the attack came on a Jewish holy day. After the United States agreed to aid Israel, Arab countries that were part of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) stopped oil shipments to the United States and cut oil production to raise prices. Oil exports from the Middle East to the West were down and the price of oil increased by almost four times from $2.90 a barrel to $11.65 a barrel. The oil embargo ended in March 1974, however periodic crises in the Middle East and conflicts between the United States and oil-producing nations led to oil and gas shortages and higher fuel prices again at the end of the 1970s, in the 1980s, and 1990s. Then in 1978, the Egyptian

President Anwar el Sadat, surprised the world by visiting Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. President Jimmy Carter wanted to bring peace to the Middle East by inviting the two leaders to Camp David. There, the leaders hammered out the terms for a peace treaty known as the Camp David Accords. In 1979, Egypt and Israel signed a peace treaty based on the Camp David Accords:

- Israel was to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt.

- Egypt formally recognized Israel as an independent nation.

- Israel and Egypt pledged to respect the border between them.

Although the two leaders signed the treaty in 1979, other Arab nations still refused to recognize Israel. Sadat was later assassinated by Muslims opposed to Sadat’s goals for peace. In 1979, President Carter was faced with a second oil crisis. A political revolution in Iran caused a major cutback in that country’s oil production. This reminded Americans that they were at the mercy of OPEC and upheavals in the Middle East. President Carter had already persuaded Congress to set up a new cabinet department-the Department of Energy. He urged the department to expand its search for practical forms of energy other than oil.

Turn and Talk/ Check for Understanding: Briefly describe the relations between the Middle East and the United States during the 1970’s. Note your findings below:

Activity #2: Students will complete an SEQ 1 task

Task: Read and analyze the following documents, applying your social studies knowledge

and skills to write a short essay of two paragraphs in which you:

- Describe the historical context surrounding these documents

- Identify and explain the relationship between the events and/or ideas found in these documents

(Cause and Effect, or Similarity/Difference, or Turning Point) - In developing your short essay answer of two or three paragraphs, be sure to keep these explanations in mind:

o Describe means “to illustrate something in words or tell about it”

o Historical Context refers to “the relevant historical circumstances surrounding or connecting the events, ideas, or developments in these documents”

o Identify means “to put a name to or to name”

o Explain means “to make plain or understandable; to give reasons for or causes of; to show the logical development or relationship of”

o Types of Relationships:

o Cause refers to “something that contributes to the occurrence of an event, the rise of an idea, or the bringing about of a development”

o Effect refers to “what happens as a consequence (result, impact, outcome) of an event, an idea, or a development”

o Similarity tells how “something is alike or the same as something else”

o Difference tells how “something is not alike or not the same as something else”

o Turning Point is “a major event, idea, or historical development that brings about significant change. It can be local, regional, national, or global.

- Document 1: “Policies to Deal with the Energy Shortages”, Richard Nixon, Address to the Nation about policies to deal with energy shortages. November 7th, 1973

“As America has grown and prospered in recent years, our energy demands have begun to exceed

available supplies. In recent months, we have taken many actions to increase supplies and to reduce

consumption. But even with our best efforts, we knew that a period of temporary shortages was

inevitable. Unfortunately, our expectations for this winter have now been sharply altered by the recent conflict in the Middle East. Because of that war, most of the Middle Eastern oil producers have reduced overall production and cut off their shipments of oil to the United States. By the end of this month, more than 2 million barrels a day of oil we expected to import into the United States will no longer be available. We must, therefore, face up to a very stark fact: We are heading toward the most acute shortages of energy since World War II. Our supply of petroleum this winter will be at least 10 percent short of our anticipated demands, and it could fall short by as much as 17 percent . . . To be sure that there is enough oil to go around for the entire winter, all over the country, it will be essential for all of us to live and work in lower temperatures. We must ask everyone to lower the thermostat in your home by at least 6 degrees so that we can achieve a national daytime average of 68 degrees . . . I am also asking Governors to take steps to reduce highway speed limits to 50 miles per hour. . . . Proposed legislation would enable the executive branch to meet the energy emergency in several important ways: First, it would authorize an immediate return to daylight saving time on a year round basis. Second, it would provide the necessary authority to relax environmental regulations on a temporary, case-by-case basis . . . Third, it would grant authority to impose special energy conservation measures, such as restrictions on the working hours for shopping centers and other commercial establishments.” - Document 2: “Moral Equivalent to War” President Jimmy Carter, Address to the Nation. April 18, 1977

“I want to have an unpleasant talk with you about a problem that is unprecedented in our history. With the exception of preventing war, this is the greatest challenge that our country will face during our lifetime. The energy crisis has not yet overwhelmed us, but it will if we do not act quickly. It’s a problem that we will not be able to solve in the next few years, and it’s likely to get progressively worse through the rest of this century . . . . By acting now we can control our future instead of letting the future control us. Two days from now, I will present to the Congress my energy proposals . . . Many of these proposals will be unpopular. Some will cause you to put up with inconveniences and to make sacrifices. The most important thing about these proposals is that the alternative may be a national catastrophe. Further delay can affect our strength and our power as a nation. Our decision about energy will test the character of the American people and the ability of the President and the Congress to govern this Nation. This difficult effort will be the “moral equivalent of war,” except that we will be uniting our efforts to build and not to destroy . . . The 1973 gas lines are gone, and with this springtime weather, our homes are warm again. But our energy problem is worse tonight than it was in 1973 or a few weeks ago in the dead of winter. It’s worse because more waste has occurred and more time has passed by without our planning for the future.

And it will get worse every day until we act . . . [W]e must reduce our vulnerability to potentially

devastating embargoes. We can protect ourselves from uncertain supplies by reducing our demand for oil, by making the most of our abundant resources such as coal, and by developing a strategic petroleum reserve.”

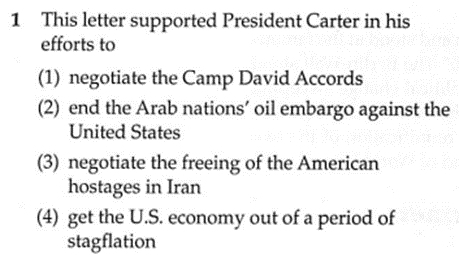

Closure: Read the letter to President Carter and answer the multiple-choice questions.

- Aim: What role did the United States play in the Middle East in the post-World War II era?

Objective: U.S. History 11th Grade. SWL about the relations between the U.S. and Middle East

following World War II by completing an SEQ 2 task.

New York State Social Studies Standards: 11.9 c: American strategic interests in the Middle East grew with the Cold War, the creation of the State of Israel, and the increased United States dependence on Middle Eastern oil. The continuing nature of the Arab-Israeli dispute has helped to define the contours of American policy in the Middle East.

Next Generation Learning Standards for Reading and Writing: - Cite specific text evidence

- Provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text

- Determine whether earlier events caused later ones or simply preceded them

- Determine the meaning of words as they are used in a text

- Write explanatory text with relevant and sufficient facts, concrete details, and appropriate examples

- Use precise language and domain specific vocabulary

- Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate

to task, purpose, and audience

Procedure:

- Do Now: Students will read the except and note the main ideas found.

- Mini-Lesson: Masterful read of the information. While reading, students will annotate and note the

possible causes for conflict in the Middle East - Learning Activities

- Turn and Talk: What would you say was the main cause for the United States involvement in the

Middle East following WWII? - Students will read the document and will complete the SEQ 2 task for either purpose or POV.

Do Now: Based on the following excerpt note the main ideas found in the text.

Questions:

1.What do you think the purpose was in creating this text?

2.From what point of view do you believe this was written? Why?

Purpose: The reason an author wrote something. Examples are to inform, entertain, persuade, describe.

Point of View: side from which the creator of a source describes a historical event.

American strategy became consumed with thwarting Russian power and the concomitant (related)

global spread of communism. Foreign policy officials increasingly opposed all insurgencies or

independence movements that could in any way be linked to international communism. The Soviet

Union, too, was attempting to sway the world. Stalin and his successors pushed an agenda that included not only the creation of Soviet client states in Eastern and Central Europe, but also a tendency to support leftwing liberation movements everywhere, particularly when they espoused anti-American sentiment. As a result, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) engaged in numerous proxy wars in the Third World. American planners felt that successful decolonization could demonstrate the superiority of democracy and capitalism against competing Soviet models. Their goal was in essence to develop an informal system of world power based as much as possible on consent (hegemony) rather than coercion (empire). But European powers still defended colonization and American officials feared that anticolonial resistance would breed revolution and push nationalists into the Soviet sphere. And when faced with such movements, American policy dictated alliances with colonial regimes, alienating nationalist leaders in Asia and Africa. Source: Michael Brenes et al., “The Cold War,” in Ari Cushner, ed., The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018).

- Directions: Do a close read of the following text passage and annotate

The Region’s Strategic Importance

After World War II, the United States began taking a more active and

interventionist role in political and military conflicts across the globe. This

was a marked break from the country’s mainly isolationist approach to world

affairs in its first 150 years. The Middle East has been the most consistent

region for U.S. intervention over the past 70 years, especially after War II

ended beginning with the creation of the State of Israel. In 1947, the United

Nations voted to divide British-controlled Palestine into two states-one Arab

and one Jewish. The U.N. action resulted in violence between Jews and

Arabs. In May 1948, Israel declared itself an independent state. Both the

United States and the Soviet Union supported this development. Most Arab

nations objected to U.S. support of Israel even though they too received U.S.

economic aid. Arab resentment against both Israel and the United States grew

in the postwar years. This allowed the Soviet Union to gain influence in the

Middle East, especially in Syria. In 1957, President Eisenhower moved to

address this spreading Soviet influence. He established the U.S. policy of

sending troops to any Middle Eastern nation that requested help against

communism. The Eisenhower Doctrine was first tested in Lebanon in 1958.

The presence of U.S. troops in Lebanon helped that country’s government

deal successfully with a Communist challenge.

The history of the Middle East in modern times has been marked by civil

wars, revolutions, assassinations, invasions, and border wars. In dealing with

each conflict, U.S. policymakers tried to balance three main interests:

- Support to the democratic State of Israel

- Support for Arab states to ensure a steady flow of Middle Eastern oil to the

United States and its allies - Prevention of increased Soviet Union influence in the region

Turn and Talk/ Check for Understanding: What would you say was the main cause for the United

States involvement in the Middle East following World War II?

Task: Read and analyze the documents. Applying your social studies knowledge and skills to write a

short essay of two or three paragraphs in which you: Describe the historical context surrounding the

Special Message to Congress by President Eisenhower and explain how audience, or purpose, or bias, or point of view affects this document’s use as a reliable source of evidence.

Document: President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Special Message to Congress, January 5, 1957

“The reason for Russia’s interest in the Middle East is solely that of power politics. Considering her

announced purpose of Communizing the world, it is easy to understand her hope of dominating the

Middle East. This region has always been the crossroads of the continents of the Eastern Hemisphere. The Suez Canal enables the nations of Asia and Europe to carry on the commerce that is essential if these countries are to maintain well-rounded and prosperous economies. The Middle East provides a gateway between Eurasia and Africa. Then there are other factors which transcend the material. The Middle East is the birthplace of three great religions-Moslem, Christian and Hebrew. Mecca and Jerusalem are more than places on the map. They symbolize religions which teach that the spirit has supremacy over matter and that the individual has a dignity and rights of which no despotic government can rightfully deprive him. It would be intolerable if the holy places of the Middle East should be subjected to a rule that glorifies atheistic materialism. International Communism, of course, seeks to mask its purposes of domination by expressions of good will and by superficially attractive offers of political, economic and military aid. Under all the circumstances I have laid before you, a greater responsibility now devolves upon the United States … The action which I propose would … authorize the United States to cooperate with and assist any nation or group of nations in the general area of the Middle East in the development of economic strength dedicated to the maintenance of national independence. It would [also] authorize such assistance and cooperation to include the employment of the armed forces of the United States to secure and protect the territorial integrity and political independence of such nations. This program will not solve all the problems of the Middle East. The United Nations is actively concerning itself with all these matters, and . . . we are willing to do much to assist the United Nations in solving the basic problems of Palestine. Source: President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Special Message to Congress, January 5, 1957

Short Essay Question Paragraph Outline: In developing your short essay answer of two or three

paragraphs, be sure to keep these explanations in mind –

Describe means “to illustrate something in words or tell about it.” Historical Context refers to

“the relevant historical circumstances surrounding or connecting the events, ideas, or

developments in these documents.” Analyze means “to examine a document and determine its

elements and its relationships.” Explain means “to make plain or understandable; to give reasons

for or causes of; to show the logical development or relationship of.” Reliability is determined by

how accurate and useful the information found in a source is for a specific purpose.

Paragraph 1: Historical Context (Complete whatever information is applicable to the topic)

Topic Sentence:

Who (was involved)? What (happened)? Where (did it happen)? When (did it happen?) Why (did it

happen?)

Paragraph 2: Reliability

Topic Sentence:

The document is (possible responses: not, somewhat, very) reliable.

Based on the (purpose OR point of view (Choose 1) ______________

Document evidence ________________________________________

Paragraph 3: Significance of the document evidence

Closing Sentence:

Aim: Why did the Crusades occur?

Do Now: Read the poem and look and the image below. Pick a sentence that stands out to you. What do you think this sentence says about how the author feels about the land ?

To Our Land

By Mahmoud Darwish

To our land,

And it one near the word of god,

To our land,

And it is the one tiny as a sesame seed

To our land , and it is the prize of war

The freedom to die from longing and burning and our

land, in its bloodiest night, is a jewel that glimmers for

the far upon the far.

Historical Context : The Crusades were a series of wars (1050-1300 CE) during the Middle Ages where the Christians of Europe tried to retake control of Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the Muslims. Jerusalem was important to a number of religions during the Middle Ages.

● It was important to Jewish people as it was the site of the original temple to God built by King

Solomon.

● It was important to the Muslims because it was where they believe the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven.

● It was important to Christians as it is where Christianity began. They considered it the Holy Land.

Check for understanding:

A major goal of the Christian Church during the Crusades (1096–1291) was to

1) establish Christianity in western Europe

2) capture the Holy Land from Islamic rulers

3) unite warring Arab peoples

4) strengthen English dominance in the Arab world

- Which point of view was this written from? Crusader (Christian), Muslim

- Identify at least two words, sentences, or phrases in this source that illustrate its point of view.

- How do they feel about the crusades?

Document A: Kingdom of Heaven – Clash of Cavalry

Directions: Read the documents below and use textual evidence to figure out the point of view

“Finally, our men took possession of the walls and towers, and wonderful sights were to be seen. Some of our men cut off the heads of their enemies; others shot them with arrows, so that they fell from the towers. It was necessary to pick one’s way over the bodies of men and horses. In the Temple of Solomon, men rode in blood up to their knees and bridle reins. Indeed, it was a just and splendid (excellent) judgment of God that this place should be filled with the blood of the unbelievers.”

Questions

Document B

“Refugees reached Baghdad and told the Caliph’s ministers a story that wrung their hearts and brought tears to their eyes. They begged for help, weeping so that their hearers wept with them as they described the sufferings of the Muslims in that Holy City: the men killed, the women and children taken prisoner, the homes pillaged.”

Questions

- Which point of view was this written from? Crusader (Christian), Muslim

- Identify at least two words, sentences, or phrases in this source that illustrate its point of view.

- How do they feel about the crusades?