New Jersey Council for the Social Studies

Engaging High School Students in Global Civic Education Lessons in U.S. History

The relationship between the individual and the state is present in every country, society, and civilization. Relevant questions about individual liberty, civic engagement, government authority, equality and justice, and protection are important for every demographic group in the population. In your teaching of World History, consider the examples and questions provided below that should be familiar to students in the history of the United States with application to the experiences of others around the world.

These civic activities are designed to present civics in a global context as civic education happens in every country. The design is flexible regarding using one of the activities, allowing students to explore multiple activities in groups, and as a lesson for a substitute teacher. The lessons are free, although a donation to the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies is greatly appreciated.

Era 4 Civil War and Reconstruction

The Civil War put the constitutional government of the United States to its severest test. It challenged the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches of government as well as the federal system of power with state and local government. The activities below provide an opportunity to learn about the breakdown of a democratic political system, the conflict between geographic regions and different subcultural, and the competitive ideas for reconstruction. Students will learn about the hope regarding equality for black Americans through the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments and the resistance leading to disenfranchisement, segregation, and debt peonage.

Activity #1: The Dred Scott Decision (1857), Magna Carta (1215), and Johnson-Reed Immigration Act (1924)

Did the Supreme Court have jurisdiction to hear the case? The law suit was properly in federal court only if a “citizen” of one State was suing a “citizen” of another State. Sanford was a citizen of New York. Even if we assume, with Scott, that the law made him a free man, was he then a “citizen” of Missouri? If Scott was a “citizen” and jurisdiction was proper, then what about the basic issue on the merits? Did the law make Scott a free man?

Was the Dred Scott Decision a failure of the Judicial system in the United States because it violated the fundamental principle in the Magna Carta regarding the rule of law and the individual rights and liberties of all people, regardless of their estate or condition. Article 39 of the Magna Carta, secured a promise from the monarchy that “no free man shall be arrested or imprisoned, or disseized or outlawed or exiled or in any way victimized, neither will we attack him or send anyone to attack him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” In the fourteenth century, Article 39 was redrafted by Parliament to apply not only to free men but also to any man “of whatever estate or condition he may be.”

The Supreme Court’s conclusion: It “is the opinion of the Court that the act of Congress, which prohibited a citizen from holding and owning property of this kind . . . is not warranted by the Constitution and is therefore void; and that neither Dred Scott himself, nor any of his family, were made free by being carried into this territory, even if they had been carried there by the owner with the intention of becoming a permanent resident.”

How do the principles of the Magna Carta and the precedent of the Dred Scott decision apply to the restrictive immigration decisions legislated by Congress in the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924? Does the United States, or any country, have the authority to restrict immigration based on race, ethnicity, or geographic location? Aliens in the United States do not have a right to a court-appointed attorney, Miranda rights, the right to a jury trial, or the right to see all the evidence against them. However, they have the protection of the Due Process of Law clause.

But one constitutional right that applies to aliens in removal proceedings is Due Process. According to the Supreme Court: “The Due Process Clause applies to all “persons” within the United States, including aliens, whether their presence here is lawful, unlawful, temporary, or permanent. Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company, (1886)

Questions:

- Did the U.S. Supreme Court have the authority to issue an obiter dictum regarding Mr. Dred Scott?

- Did enslaved persons who received freedom also become citizens of the state where they lived? Would their status as citizens change because of their race or ethnicity if they moved to another state?

- Does Article 39 of the Magna Carta apply to free blacks who were arrested as fugitives?

- Do people living in America, who are not citizens, entitled to rights in addition to the due process of law and should they also receive the equal protection of the laws of the United States?

- What about people living in America who entered illegal or have expired documents?

- Should birthright citizenship, everyone born in the United States or one of its territories, be considered a full citizen regardless of the status of their immigrant parent(s)?

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer’s Address to the Supreme Court Historical Society on June 1, 2009

Slavery and the Magna Carta in the development of Anglo American Constitutionalism

The Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act)

The 1924 Act that Slammed the Door on Immigrants and the Politicians who Pushed it Back Open

Activity #2: Secession of Southern States (1861) and the Secession of Bangladesh from East Pakistan (1971)

The question is whether the Southern states possessed the legal right to secede. Jefferson Davis, president of the new Confederate States of America, argued that the Tenth Amendment was the legal basis for secession. The U.S. Constitution is silent on the question of secession. Therefore, secession is a right reserved to the states and is supported by the ‘compact theory’ regarding the right to nullify a federal law.

Another argument in support of the right of secession involves the states of Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island because these states included a clause in their constitutions that permitted them to withdraw from the Union if the government should become oppressive. Virginia cited this provision when it seceded in 1861. The Constitution is also based on the principle that all the states are equal and no state can have more rights than another. The right of secession cited by these three states must extend equally to all the states. This is an interesting question for debate and discussion.

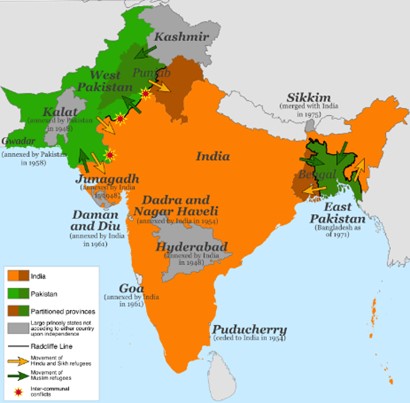

In 1971, the Pakistan army launched a brutal campaign to suppress its breakaway eastern province. A large number of people lost their lives, an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 died. The Bangladesh government puts the figure at three million. Bangladesh seceded because of the oppressive genocide against their population. It is now more than 40 years since they became an independent country.

Questions:

- Do the “opt out’ clauses by Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island support secession at a later date from an early agreement to join into the common government or the Union?

- If a government violates the natural rights of life, liberty, property, or the pursuit of happiness against a specific group of people or a state, do they have the right to secede?

- Would you support the secession of Bangladesh if less than 1,000 people were killed?

The Secession of East Pakistan in 1971 and the Question of Genocide

The Secession of Bangladesh in International Law: Setting New Standards?

Activity #3: Emancipation Act of 1863, 13th Amendment, Civil Rights Act of 1866

Historians and constitutional scholars question if the Emancipation Proclamation was constitutional. This is a different question than asking if the Proclamation was justified. The debate over constitutionality is based on the question if it was lawful to own another human being if you lived in a state that was loyal to the Union. The Supreme Court in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) upheld the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 stating that Pennsylvania could not prevent the return of a fugitive slave to its owner. Consequently, The Thirteenth Amendment was necessary to make the Emancipation Proclamation constitutional.

On January 5, 1866, a few weeks after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, Senator Lyman Trumbull, from Illinois, introduced the first federal civil rights bill in our history. President Andrew Johnson vetoed the bill, opposing laws for the equality of African Americans as compared to the natural progression for this to happen over time. The veto message incensed Congress, who had evidence of widespread mistreatment of African Americans throughout the South by both private and public parties. Congress overrode Johnson’s veto on April 9, 1866, and elements of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 eventually became the framework for the Fourteenth Amendment. The constitutional question relates to the argument if the Act applies only to states that discriminate or if it applies to both state governments and private citizens.

Questions:

- Does the U.S. Constitution need to explicitly state that all human beings are guaranteed life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?

- Did the Civil Rights Act of 1866 go too far or was it too limited in prohibiting discrimination?

- Should the Thirteenth Amendment have included a provision for reparations for enslaved persons and a provision for compensating slave owners for their losses?

Emancipation Proclamation (National Archives)

Was the Emancipation Proclamation Constitutional? (Illinois Law Review)

Origin and Purpose of the Thirteenth Amendment (Cornell Law School)

Racial Discrimination and the Civil Rights Act of 1866

Activity #4: 14th Amendment and the Miranda Decision

The 14th amendment explicitly contains an equal protection clause. Miranda warnings and other amendments were not only created to protect certain individuals but all individuals. Equal protection is a foundational principle in our society. No one should have their rights unjustly taken away from them; and no one should be allowed to get away with crimes because of their ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, etc. Everyone is under the rule of law.

An uneducated or uninformed individual may be pressured by authorities in an interrogation and confess to a crime they did not commit in order to stop the questioning. The right to remain silent and the right to an attorney ensures that all individuals get equal protection regarding of their situation or circumstance.

Questions:

- Does Miranda provide adequate protections for accused persons?

- Does the right to remain silent benefit an innocent person who is detained or accused?

- Should a detained or accused person have to specifically state and document their request to remain silent?

- Do the police have to stop questioning after a person states their intention to remain silent?

- If the police need information two or three weeks after the initial detainment, do they need to repeat the Miranda warning a second time?

- Should Miranda warnings apply to juveniles in school or only in matters involving questions by the police?

Fourteenth Amendment(Cornell Law)

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology(Northwestern University School of Law, 1996)