Slavery and Resistance in the Hudson Valley

A.J. Williams-Myers, State University of New York-New Paltz

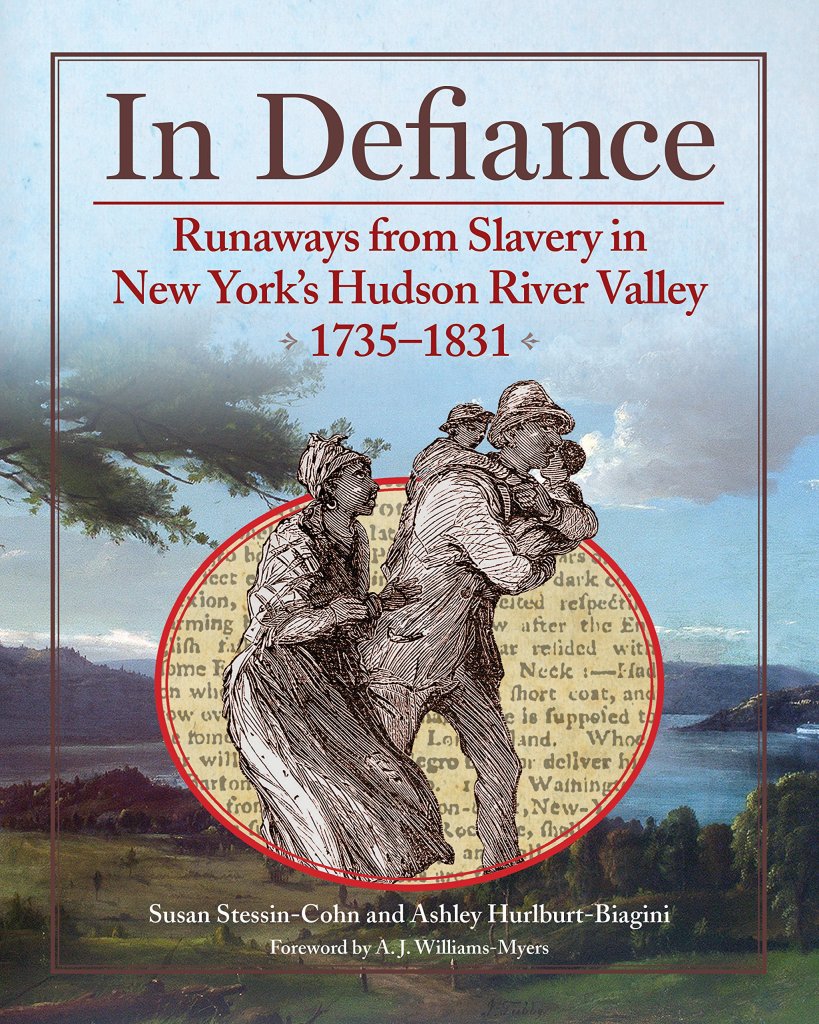

This article is excerpted from the forward to In Defiance: Runaways from Slavery in New York’s Hudson River Valley, 1735-1831 by Susan Stessin-Cohn and Ashley Hulburt Biagini (Black Dome Press, 2016).

In 1805, Ann B. Long of Wappings Creek, Dutchess County, New York, placed a notice for the return of Mary, a young female runaway slave. Long had searched for Mary three years prior, when she fled enslavement at the age of 13. Newspaper notices offering rewards for the capture and return of enslaved human beings were increasingly common in the 18th and early 19th century Hudson River Valley until slavery was officially abolished in New York State in 1827. These notices provide thought provoking glimpses into the lives of New York State’s enslaved population and are the only records that exist for many of the individuals described in the notices.

The vast number of runaway slave notices in this period are indicative not only of how widespread the institution of slavery was in the Hudson Valley, but also speaks to the magnitude of the struggle for freedom being fought by an oppressed and enslaved people. The dangers of running and the consequences if caught were dire and had to have struck abject fear into the hearts of those contemplating such a feat. Yet, for many, the opportunity to live as a human being, out of bondage, able to breathe the air in freedom, was worth the dangers. It was a courageous choice.

The large number of runaway slave notices also gives us a clue to the increasing importance that the enslaved labor force had become to the rise of a vibrant Hudson Valley socioeconomic system. There was an insatiable need for labor in the economic exploits of first the colonial Dutch and later the English. Both colonial powers initially failed to lure families of white tenant farmers to New York to labor on the big estates of the Dutch patroonships and English manors carved out of prime agricultural land in the Hudson Valley. Even with white indentured servants and Native Americans in the workforce, more hands were needed. That labor shortfall was solved through the Atlantic Connection. The Atlantic Connection included the labor-recruiting ground of Africa, the West Indies, and the mainland British colonies of Virginia and South Carolina. Africans had become chattel through capture and sale, were taken across the Atlantic, and were enslaved in the West Indies and the American South. From there, some were sold to Northern owners, although many of the enslaved came directly to the North from Africa.

The runaway slave notices are stark indices of a nation out of step with the tenets of its foundation. Early settlers in the Hudson Valley immigrated to escape political and religious persecution, and yet, upon their arrival here, they saw fit to participate in a culture that removed others involuntarily from their home-lands and forced them to labor for the economic development of a community in which they had no rights. These notices paint a contradictory and inconsistent picture of the nature of slavery juxtaposed against the articulated philosophy of democratic and Christian principles espoused by the enslavers.

Hudson Valley slavery was initially an institution characterized under the Dutch as a “Matter of Custom” where the African as “half free” maneuvered through somewhat of a more open system from 1626 to 1664. As described by Vivienne Kruger, though slavery was a Matter of Custom, “freed Negroes were not legally discriminated against –- no racial legislation existed to restrict their freedom to own property, intermarry with whites, or own white indentured servants.” Nevertheless, the Dutch “[were] vehement supporters of slavery,” as is evident by the inhumane version of the institution constructed under the Dutch West India Company and its holdings in the Caribbean. The time factor (1626-1664) for implanting that version in New Netherlands was cut short with England’s conquest of the colony. Consequently, slavery as a “Matter of Custom” soon metamorphosed under the English into a more viciously closed system, restricting the enslaved African’s access to freedom given that slavery was now characterized by law.

Ann B. Long’s runaway is a “girl named Mary.” Clearly prominent in the notice is the fact of miscegenation; Mary the runaway is described as a mulatto, evidence that despite the degenerative racial classification of the enslaved as less than whites, sexual racial lines were crossed. According to Long, “the reason of her being now advertised is that I have heard of her being at the Nine Partners.” Long is moved to action with the notice three years later because of where Mary was seen, at Nine Partners among the Quakers, longstanding antislavery advocates who would protect Mary – and thus the likelihood that Long could lose her human property.

Why and when Mary decided to become a runaway in defiance of her enslaved status can only be conjectured. Were there family members of hers at Long’s who might have been sold off or fled earlier? Or was she aware of the fact that the 1799 Gradual Emancipation Act was not an articulation for her freedom, but only for those born after that year, and thus her flight from slavery was the only way she might be able to clutch freedom before she died? Mary’s run for freedom positioned her with others who ran before her and after her on a historical continuum stretching back to capture in Africa, through the dreadful Middle Passage, and American enslavement- an integral part of an endless stream of runaways in search of freedom not far distant.

Mary the runaway sought freedom in the shadow of the story of Southern slavery. Her flight from slavery in New York’s Hudson Valley was overwhelmed by that other larger story with its romanticized view of “encouraging the finer moral instincts of paternalism” in the “peculiar institution.” Perhaps Mary was seen as “troublesome property” in a peculiarly psychological model of slavery and represented resistance amid the cries of revolt and revolution. Yet, though overshadowed by that larger Southern story of slavery in America, Mary’s flight was part and parcel of that story as “the violent world surrounding [and engulfing Mary] was a microcosm of in extremis of the American slave system.” The sadism, cruelty, violence, passion, flight, and rebellion, and all the demonical acts of inhumanity perpetrated by the enslaver against the enslaved, so characteristic of Southern slavery, endemically riddled, as well, the very core of Mary’s world- Northern slavery.

Mary’s quest for freedom and the quests of others in these notices reveal images of runaways etched up and down the valley from its most northern extent to its southern terminus abutting New York City. It is an interesting, engaging, and revealing, though at times gripping, view of humanity as chattel in flight from a diabolical instrument of oppression at the hands of fellow humans for the expressed purpose of economic gain. This portraiture, pieced together through the array of runaway notices, is a trove of descriptive information of who the runaways were, to whom they belonged as human property, with whom they ran, their age range, the talents/skills they possessed, their personality characteristics, and their body abrasions/scars- often the end results of violent encounters with their owners. Such master/enslaved encounters “expose the violence and cruelty that were inherent in the slave system.”

Images of that violence and cruelty are evident in that portrait- as characterized by the owner himself in his notice – of the “Indian Servant Wench” in flight from her bondage in North Castle in Westchester County. Kate is 15 years of age and, as a mark of human indignity, she is strapped with an iron collar about her neck as a statement of ownership.

James Gale is a runaway from Judge Horsmanden in New York City. Captured and jailed at Goshen in Orange County, James’s face carries the abrasions/scars of the horrors to which the enslaved were subjected. He has a large scar across his nose, several on his right temple and head, and a large bump on his forehead. James is 23. He and Kate are just two of the many who were subjected to violence and cruelty to make them stand in fear.

The gripping portrayal of Hudson Valley enslaved runaways cries out in silence for refuge. It is no different than the portraiture of that other larger Southern world of slavery, whose images continue to haunt the descendants of both the enslaved and the enslaver. The only difference is scale.

Runaway Slave Ads from Hudson Valley

Source: Hodges and Brown, ed. Pretends to be Free (NY: Garland, 1994)

Instructions

- List the Hudson Valley towns and counties mentioned in the ads.

- List between three and five ways freedom seekers are identified in the ads.

- What conclusion (s) can you draw from the spelling and grammar in the ads?

- In Ad “D”, why does Chauncy Graham believe Cuff was added in his escape by a white man?

- In Ad “E”, Peter is described as a Mollatto or a Mullato. In your opinion, what does this tell us about Peter?

- According to Ad “F”, how was Tom able to get a “false Pass”?

- In Ad “J”, how was Sambo able to get a pass?

- Some of the freedom seekers pretended to be free. What does that tell us about the Hudson Valley at that time?

A. The New-York Gazette, Revived in The Weekly Post-Boy, #227, April 20, 1747. Run away from Theunis De Klerk of Tappan in Orange County, a Negro Man named Sippee, about 30 years of age, of a middle size, is well-set, speaks good and proper English, and has a hoarse voice: Had on when he went away, a brown short watch-coat, a light colour’d red Jacket, a white Jacket bound round the edges with some other colour, and a Felt hat cock’d up and flattened on the Crown. Whoever takes up said Negro and brings him to his Master, or unto William Vredenburgh of New York shall have 40s reward and all reasonable charges paid by Theunis De Klerk.

B. The New-York Weekly Journal, #253, October 2, 1738. Run away from Frederick Zepperly of Rheinbeck in Dutchess County Black Smith, a copper coloured Negro fellow named Jack, aged about 30 years, speaks nothing but English and has been much used to the Sea, Short of Stature, thin Face, strong bearded and hair longer than Negros commonly have and reads English, he had on when he went away an Orange Coloured Drugget Fly Coat somewhat faded, with brass Buttons a Homespun Linnen Coat, two striped Linsey Wolsey Waistcoats and two pair of Breeches the same also one pair of Leather Breeches a pair of Worsted Stockings and a pair of New Blew Yarn stockings, New square toes Shoes with Brass Buckles two homespun Shirts and a very good Hat. Whoever takes up said Run away and secures him so that his Master may have him again or gives notice of him to Henry Beekman, Esq or to John Peter Zenger shall have Forty Shilling reward and all reasonable Charges.

C. The New-York Gazette: or, The Weekly Post-Boy, #542, June 18, 1753. Run away on Sunday the 3rd day of May last, from Jacobus Bruyne, of Bruynswick, in county of Ulster and province of New York, a Negroe Man Slave, named Andrew, aged near 40 year, he is of middle Stature, black skin’d, speaks good English and Dutch: had on when he went away, a coarse Linnen jacket and Trowsers, old shoes and stockings, he has been formerly out of a Privateering with Capt. Tingley, and it is supposed he may attempt to get on board some Vessel carrying him off at their peril. Whoever takes up and secures Said Negroe, so that his master may have him again, shall have Forty Shillings reward, and all reasonable Charges paid by JACOBUS BRUYNE.

D. The New-York Gazette; or, The Weekly Post-Boy, #558, October 15, 1753. Run away on Sabbath Day evening, Sept. 2, 1753, from his Master Chauncy Graham, of Rumbout, in Dutchess County, a likely Negroe Man named Cuff, about 30 years old, well set, has had the Small Pox, is very black, speaks English pretty well for a Guinea Negroe, and very flippant; he is a plausible smooth Tongue Fellow. Had with him a pair of greenish plush breeches about two-thirds worn, and a Pair of russel ditto flowered green and yellow, two white shirts, two Pair of middling short Two Trowsers, one pair of Thread Stockings knit in Squares, one Pair of blue fine wool ditto flowered, one Diaper Cap, one white Cotton ditto, one blue Broad Cloth Jacket with red lining, one blue homespun coat lined with streak’d Lindsey Woolsey, or woolen &c. &c. &c. He is a strong Smoaker. ‘Tis supposed he was seduced away by one Samuel Stanberry, alias Joseph Linley, a white fellow that run away with him, and ‘tis very likely this white man has wrote the Negro a pass; for ‘tis said he has been in Norwalk in Conecticut, and passed there for a free Negro, by the name of Joseph Jennings, and that he was making toward the Eastward. Whoever shall take up and secure said Servant, so that his Master may have him again, shall have FORTY SHILLINGS New-York Money Reward, and all reasonable charges paid by CHAUNCY GRAHAM.

E. The New-York Gazette, Revived in The Weekly Post-Boy, #278, May 16, 1748. Run away the 8th of this instant, from Colonel Francis Brett of the Fish Kills, in Ulster County, a Mollatto slave named Peter, 20, 6 feet high, pretty fair for a Mullato but Negro hair, a scar over both his eyes had on a yellowish Fly Coat of a Broad Cloth, Leather Breeches, grey homespun Stockings, a Beaver Hat, a grey homespun Jacket, a Linnen Shirt, and a Tow Cloth Shirt. Whoever takes up said Negro, and gives Notice to his said Master, or to the Printer hereof,

F. The New-York Gazette: or, The Weekly Post-Boy, #635, March 3, 1755. Run away from the Heirs of Barent Van Cleek, of Poughkeepsie, deceased on Tuesday the 23rd Instant March, a Mulatto colour’d Man Slave named Tom, pock-broken, about 5 feet 10 inches high, a well set likely Fellow, plays well on the Fiddle, and can read and write; perhaps he may have a false Pass: Had on when he went away, a red plush breeches, a full trim’d Coat, a cloth Jacket, and it’s supposed several other clothes: took with him a bay Horse about 13 hands and a half high with a [ ] on his fore head, bridle and sadle: whoever takes up said Negroe, and delivers him to Poughkeepsie, or secures him in a goal, and gives notice thereof to Leonard Van Cleek, or Myndert Veile, of Duchess County, shall receive five Pounds Reward, and all reasonable charges paid by LEONARD VAN CLEEK and MYNDERT VEILE.

G. The New-York Gazette: or, The Weekly Post-Boy, #768, October 10, 1757. Run away from Caleb Ferris, of East-Chester, a Negro Man slave called Joe, aged about 25 years. He is a lusty well fed Fellow every Way, about five Feet Ten inches, thick shoulder’d full round Face, speaks altogether English, his Hair frizzled, being half Indian. He has been voyage privateering, and is a great Fiddler. He has a large Leg and broad Foot, and commonly wears Sailors Habit. He was born at Westchester, and sometimes pretends to be free. Whoever takes up the above described Slave, and will secure him so that his Master can have him again, shall have Six Pounds Reward, paid by CALEB FERRIS.

H. The New-York Gazette; or, The Weekly Post-boy, #1030, September, 30, 1762. Tappan, Sept. 26, 1762. RUN away last Sunday Evening, from his Master, in Orange County, Johannes Blauveldt, Blacksmith, a Negro Fellow, named as he says, Adonia, but by us Duca, he is a yellow Complexion, being a mixed Breed, speaks and reads pretty good Low Dutch, and speaks little English: is a very good Black Smith by Trade, and can make Leather Shoes, and do some thing at the Carpenters Trade, is about 5 and a half Feet high, full Faced, black Hair, but cut off about one Inch long, is 20 or 22 Years old, had on, when he went away, homespun Trowsers, Shirt, gray Waistcoat, and Felt Hat; took with him a check Shirt and Trowsers, a white Shirt and a Pair of blue Cloth Breeches, and one home spun Waist Coat, he had been whip’d the day before he went off, which may be seen pretty much on his right side, he pretends to be free, and perhaps will get a Pass for that Purpose.

I. The New-York Gazette; or, The Weekly Post-Boy, #1082, September 29, 1763. RUN AWAY FROM the subscriber, at Verderica Hook, in Orange County, about Thirty Miles from New-York, on Tuesday the Twentieth Instant, a Negro Man named Harry, about Thirty Years of Age, Five Feet and a Half high, pretty well set, black Complexion, full Faced, has not had the Small Pox, speaks good English and Dutch; two Fingers on his left Hand are somewhat stiff, so that he can neither straighten them, nor shut them close; bred to farming Business: – Had a coarse white Linen Shirt, ruffled at the Boson; a narrow brimmed, half Beaver Hat; a blue broad Cloth Coat, about half worn, four Inches too long waisted for him; a striped linsy Waistcoat, and wide striped Cotton Trowsers; had with him a Pair of grey Worsted, and a Pair of old white Woolen Stockings, and a Pair of very remarkably large broad rim’d Brass Buckles – He carried with him several other wearing Clothes, viz. Two checked Woolen Shirts, blue and white; One or Two Pairs of coarse narrow homespun Tow Trowsers; and had some Money with him, wherewith he may have purchased other Clothes. Whoever secures the said Negro, giving me Notice so that I get him again, shall have Forty Shillings reward, and all reasonable Charges paid by BENJAMIN KNAP.

J. The New-York Gazette; and the Weekly Mercury, #1097, November 2, 1772. Six Pounds Reward. RUN-away from Caleb Morgan, in East-Chester, the eighteenth day of October last, a negro man named Sambo, about 25 years of age, about five feet nine inches high, of a yellow complexion, pretty slim built, a sober looking fellow: Had on when he went away, a blue broad cloth coat, with red lining; a black Manchester velvet jacket without sleeves, a pair of buckskin breeches, and blue stockings, a good pair of thick shoes, two shirts, and an old felt hat; one of his fore fingers (the tip end) is bruised off, so that the skin grows fast to the bone; the other hand the middle finger is something crooked, so that he cannot open it so straight as the others. He talks very good English, and I believe he can talk Dutch, he being brought up among the Dutch the west side of north river. It is mistrusted that a white man has carried him away in order to make sale of him, or has given him a pass; the man’s name that is mistrusted is John Norris, about 30 years of age, often goes down to the Jerseys; perhaps he may have changed his name, he is a lusty man. If any person does discover any white man with the negro, and they have made sale, or does it to make sale of him, and takes up the white man with the negro, and secures them in any of his Majesty’s goals, so that I can come get my negro again, and the white man brought to justice, shall have the above reward; or Five Pounds, and reasonable charges, for the negro alone; paid by CALEB MORGAN.