by Georgia Belesis

Art is a universal language shared by all civilizations, despite their regional, social, cultural, and economic differences. Learning history from art, changes the way history has been documented, since artistic masterpieces reveal a history that has collectively and equally been created by both males and females belonging to all socio-economic spectrums of society (Eisner, 1991). Aristotle defined art, as “capacity to make, involving a true course of reasoning,” (p.143), emphasizing that the predominant objective of art is to externally represent the internal beauty of an individuals’ endoskeleton. Art is perceived to be the first form of reasoning and communication that an individual has with the visible world. Correspondingly, the history of humanity has depicted that the earliest forms of artistic expression and communication were illustrated almost 75, 000 years ago in the caves of Lascaux, Chauvet, and Altamira. Therefore, the study of history through the aesthetics becomes the literal bridge that unifies the individual with their origins.

What are the Aesthetics?

The aesthetics are a field of study, concentrated upon the interrelated studies of the arts, music, literature, drama, visual arts, and philosophy. Aesthetic education is defined by Maxine Greene (2018) as “a process of initiating persons into faithful perceiving, a means of empowering them to accomplish the task—from their own standpoints, against the background of their own awareness” (p.45). As a veteran pedagogue of Advanced Placement World History courses who integrates the aesthetics within their instruction, I have witnessed through my own students, how the aesthetics have gradually developed their historical literacy and have also assisted them to obtain a three or better in the AP World History Examination. Therefore, I have determined based on my own pedagogical justifications and evidence-based research, that aesthetic-based teaching and learning practices have a significant impact upon Advanced Placement History Courses, since students can become emotionally connected to the past, develop their historical literacy and advance their academic performance in their Advanced Placement examinations.

How does aesthetic-based instruction within AP Courses impact students’ historical literacy and academic performance?

Aesthetic-based teaching and learning practices within Advanced Placement Social Studies Courses can emotionally connect students to the past. Historians are artists and artists are historians, since according to John Dewey (1988), “Artists have always been the real purveyors of news, for it is not the outward happening in itself which is new, but the kindling by it of emotion, perception, and appreciation” (pp. 183-184). Through works of art students become engaged in a continuous cycle of discovery between the visual, personal, and historical dimensions of that masterpiece (Greene, 2018). Learning history through the arts, “makes perceptible, visible, and audible that which is no longer, or not yet perceived, said, or heard in everyday life” (Marcuse,1977/1978, p.72), (Greene, 2018, p.49). Therefore, having students think “aesthetically” not “anesthetically” (Greene, 2018, p.49). The art of teaching is the art of questioning, which can inspire an individual to discover the unsung voice of their endoskeleton. Brooks (2013), states that “young learners have the opportunity to develop and display historical understanding when they are given the chance to formulate their own questions about the past, to examine related historical evidence, and to create historical narratives and arguments of their own” (p.61).

Art and history educators must design open-ended questions about particular pieces of art, about “art in itself and about its place in the art of human life” (Greene, 2018, p.37). Only if educators do so Greene (2018) claims, “they are likely to clarify what they bring about in their classrooms, whether they call it enhanced awareness, heightened understanding, enlightenment, or a new mode of literacy (p.37). When bulletin boards of history classes, become draped by eminent pieces of art, by Leonardo da Vinci, El Greco, Francisco Goya, Paul Cezanne, Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Frida Kahlo, among others, students become conceptually and emotionally inquisitive to learn about the art and the individuals concealed behind these illustrations (Greene, 2018).

History can be interpreted differently by an individual, through the distinct instrument of art (Eisner, 1991). Many students are visual learners, and when they study artistic masterpieces or graphic novels, they become socially and emotionally connected to these images because they directly relate them to their personal lives and become inspired to learn more about the history concealed behind those illustrations. Terrie Epstein (1997) who is an adherent of Elliot Eisner’s educational ideology, correspondingly argues that by integrating the arts into the history curriculum, educators are stimulating students to connect with the past through the process of historical empathy. “The music of the slaves, the myths and stories that were a part of their lives, their folksay, programs like Roots, the music and dance of the period, the architecture of their quarters, and those of their masters, are all relevant sources for enlarging understanding (Epstein, 1989, p. 253). Accordingly, Anne McCrary Sullivan (2000) claims that, “aesthetic vision suggests a high level of consciousness about what one sees… Teachers who function with aesthetic vision perceive the dynamic nature of what is unfolding in front of them at any given moment” (pp. 220-221). The epicenter of aesthetic education starts and continues with the cognitive and emotional pathos of the instructor, that is reflected upon the students; therefore, Greene (2018) states, that learning becomes paradigmatic, since it is stimulated by the desire to explore, to find out, to go in search” (p.47). History educators teaching Advanced Placement courses, should have the “aesthetic vision” to design intellectually stimulating lessons that encourage students to not only evaluate the history related to the aesthetic masterpieces but investigate their meaning and connection upon their lives. Through the instrument of aesthetic education students in history courses will comprehend that the past was not an invisible world, but a visible world that transcended to the present through the contributions of individuals who chose to become agents and recipients of change (Greene, 2018). Pedagogical creativity that is enhanced through the aesthetics, develops both cognitive and emotional intelligence and fosters the foundations for a learners cognitive reframing since they provide a positive and rational approach of explicating an individual’s concealed endoskeletons.

How do I implement Aesthetics into my Advanced Placement History Courses?

When I teach the Spanish Civil War in my AP World History Course, I introduce the lesson through the visual window of Picasso’s Guernica, which was his most renowned masterpiece. The lesson is an introduction to the concept of war through the critical lens of political art; exposing students to the dehumanization of war that plagued Europe and the International Community from 1936-1945. Imperatively, through this lesson, students evaluate how art can be utilized as an instrument to not only illustrate history but essentially act as a defensive symbol for social and political changes. Therefore, through the aesthetics, students are analyzing and interpreting significant multi-faceted historical pieces of the social, cultural, political, and economic progression of humanity. Subsequently, another lesson that I have designed for my AP World History Course requires students to design a virtual interview with three earlier or contemporary philosophers or artists. For example, Through the evaluation of Plato’s, Leonardo da Vinci’s and Nikos Kazantzakis’, perspectives of art, students can recognize the predominant role the aesthetics have within the development of transformative knowledge. These scholars of aestheticism collectively perceived that art is a visible expression of the invisible fragments concealed within an individual’s mind and soul. The instrumental and communicative domains of Mezirow’s (1991) transformational learning are evident within each of their ideology since they all, distinctly interpret art as an expression of cognitive and emotional intellect. The conclusions that can be retrieved from this interview is that every individual is an artist; whether they exemplify Plato’s true artist, da Vinci’s artistic scientist, or Kazantzakis’ hero-warrior artist; as human beings we innately acquire the capability of accomplishing the impossible-if we correlate the power of our minds, bodies, and souls. Consequently, art becomes the unifying bridge, which reveals the beauty of the endoskeleton through the instrument of our exoskeleton.

Correspondingly, to my aesthetic-based history instruction, Pulitzer Prize winning author, Art Spiegelman, argued that “Comics are a gateway drug to literacy”. For a history instructor, comics are an alternative pedagogical approach to develop and improve a student’s historical literacy (Robinson, 2011). Primarily, the topic I incorporate comics, through the instrument of a graphic novel within my AP World History Course, is the Arab-Israeli Conflict. The Middle East has historically been inundated as a region encompassed by religious and geopolitical dispute; it has been the primary focus of conflict that continues to have an international impact. Therefore, I have designed a summative unit project that is based upon students aesthetically formulating their own resolution to the multi-faceted Arab-Israeli Conflict (Robinson, 2011). The graphic novel that this project is culminated upon is Joe Sacco’s ‘Palestine’. I first have students read the novel individually, and then I have them critique it within their designated groups (Nass & Yen, 2012). After students have examined the novel-using it as a prototype, in addition to both primary and secondary sources, as contextual evidence, students design and illustrate their own resolution to the Arab-Israeli Conflict through the construction of a graphic novel. Subsequently, within their groups-each student is responsible for at least one visual component of the graphic novel (Nass & Yen, 2012). Art is the visual passage to history; directly linking the past with the present. Art is a universal language shared by all civilizations, despite their regional, social, cultural, and economic differences. Learning history from art, changes the way history has been interpreted, since it had been initially written from the male point of view. However, artistic masterpieces reveal a history that has collectively been created by both men and women and by individuals belonging to all socio-economic spectrums of society. Fundamentally, art represents the soul of society, it represents as Aristotle says, “the inward significance” of a society, and individuals can interpret it any way they want.

Aesthetic-based teaching and learning practices within Advanced Placement History Courses can also develop students’ historical literacy. The foundations for inquiry- based learning were first designed by Socrates whose method of questioning has established the conceptual framework for inquiry- based instruction. The case study conducted by John K. Lee and referenced by Yaeger & Davis (2005) evaluated the teaching methodology of AP European History instructor Mike Nance, who despite the pedagogical challenges he encountered with standardizing testing, his pedagogy focused upon the high order historical thinking of his students through inquiry-based instruction. Nance’s lectures encompassed dialectical discourse, which is a form of interactive explanatory pedagogy, and supports student’s conceptual and emotional interests (Yaeger & Davis, 2005). The framework of aesthetic education and aesthetic thinking is fostered upon questioning, “and the questions must multiply and not be covered by the answers” (Greene, 2018). Through inquiry-based instruction, students’ can develop their high order historical thinking in high school history classes that execute high stakes examinations.Nance’s lectures are a historical narrative focused upon the central theme of the lesson which transcend into student discussion by the level of questions that he asks his students. Nance’s primary instructional objective is to develop his student’s historical literacy, and he accomplished that, by facilitating critical thinking through questions aligned with Bloom’s Taxonomy; questions that alternatively teach, not test students about history (Yaeger & Davis, 2005). Through the obscure knowledge of the textbook, students in high school history courses have been taught to objectively study the contextual work of the source without evaluating the point of view of the author or inquire about the reasons why they wrote their work (Epstein, 1997). Accordingly, to Nance’s (Yaeger & Davis, 2005) pedagogical ideology and instruction of his advanced placement course, Eisner (1991) argues that social studies textbooks can severely limit the development of students’ historical literacy. “Thus, attention to the arts, to music, to literature in social studies programs is not a way to gussy-up the curriculum. It is a way to enlarge human understanding and to make experience in the social studies vivid” (Eisner, 1991, pg. 553). Correspondingly, to Nance’s (Yaeger & Davis, 2005) pedagogical approach, inquiry- based instruction is established in my AP world history course through dialectic discussions such as Socratic seminars. During the execution of my Socratic seminars, my students possess the autonomy to question, comment, and argue historical sources in an ethical and democratic methodology; in which they listen, respect, and are tolerant and empathetic of each other’s commentary. Through the critical discourse of Socratic seminars, one can interpret and question the validation of empirical knowledge. Consequently, with Socratic seminars my learners become active participants of an ethical democratic society.

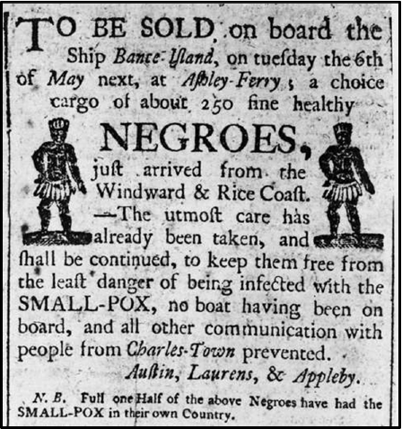

Analogously, to Nance’s (Yaeger & Davis, 2005) case study and Eisner’ (1991) ideology, in 1991, Epstein (1997) formulated a two-week American history curriculum in a Boston high school to develop students’ comprehension of the slavery period in America, through the implementation of television programs, stories, myths, music, visual art, and poetry. Through the student feedback collectively retrieved from interviews and questionnaires, Epstein (1997) argued that students commented on how the aesthetic-based curriculum provided them with a feeling and vivid illustration on what slavery was like as opposed to the summary and subjective account of facts documented in their textbook. Through this discipline arts-based integration students, Greene (2018) claims that educators can initiate their students “into what it feels to live in music, move over and about in a painting, travel round and in between masses of a sculpture, dwell in a poem” (Reid,1969, p.302), (Greene, 2018, p.8). Correspondingly, to both Eisner (1991), Epstein’s (1997) studies, and Greene’s (2018) studies, Laney (2007) in the article, Jacob Lawrence’s the migration series: Art as narrative history argues:

The natural affinity of the arts and social studies is obvious. Society and culture impact the arts, and the arts impact society and culture. The arts are a reflection, of cultural heritage, serving as vehicles for expressing diverse view- points within democracy…….Discipline-based arts educators and comprehensive arts educators advocate using works of art as organizing centers for interdisciplinary instruction. In the discipline-based arts education approach, students analyze a work of art through art history (including general history and social studies), art criticism, aesthetics, and art production. Comprehensive arts education expands the integrated approach to include nonvisual forms of art such as music, drama, theater, dance, movement, and literature…”(pg. 131).

Educators as myself who are teaching AP World History courses can utilize the studies by Epstein (1997), Laney (2007) and Greene (2018), to integrate poetry, while teaching historical content within their courses. One of the achievements that distinguish the Tang Dynasty and identify the rise and decline of their civilization is their literature. Poets such as Li Bo and Tu Fu are still considered the greatest poets produced by the Chinese civilization. Through the study and analysis of the Tang’s cultural advancements- with the principle case study being Chinese poetry, students will comprehend how the Golden Age of the Tang Dynasty changed China politically, economically, socially, and culturally. Students will also develop their cognitive skills for historiography, since they will analyze the poetry of the two predominant poets of the Tang Dynasty and evaluate the commonalities and differences of their work. Primarily, the intent for this lesson is for students to comprehend how primary sources such as poetry can reveal the political, economic, social, and cultural aspects of any earlier or contemporary civilization, which are integral to their academic performance in the AP World History examination. Consequently, through this aesthetic lesson students, will be able to collectively develop their aesthetic and historic literacy, by emotionally and conceptually connecting to the literary arts.

Service learning has become an integral constituent within the nation-wide school curriculum and specifically within the Social Studies and Advanced Placement world history curriculum. Dr. Rahima Wade (2008), has analytically evaluated educational research on service learning, defining service learning, it’s “rationale”, and application within Social Studies education. According to the Alliance for Service Learning in Education Reform (ASLER):

Service Learning is a method by which young people learn and develop through active participation in thoughtfully organized service experiences: that meet actual community needs, that are coordinated in collaboration with the school and community, that are integrated into each young person’s academic curriculum, that provide structured time for a young person to think, talk and write about what he/she did and saw during the actual service activity, that provide young people with opportunities to use newly acquired academic skills and knowledge in real life situations in their own communities, that enhance what is taught in the school by extending student learning beyond the classroom, that help to foster the development of a sense of caring for others (pg. 111).

This type of learning provides an external learning experience for the student, therefore coercing them not only to academically excel, but to become present and future active civic and political members of their society. Therefore, for my AP World History Course, I have designed an aesthetic- civic based simulation lesson on the Party Negotiations within the Conference of India between 1930-1932. These series of conferences were organized by the British Government to deliberate constitutional reforms in India. Accordingly, I divide my students into the four political and religious parties of India, to diplomatically evaluate, deliberate, and argue with their opposition about the formulation of an equitable central government for India, that would equally support all of their rights. My instructional methodology is constructed upon student directed instruction, however as the moderator and facilitator of this simulation, I will ensure that all my students explicate their intellectual excellence, guiding and encouraging them within their groups to thoroughly develop their arguments (Robinson,2011). The design and execution of this simulation focused upon my learners exhibiting high order historical thinking and substantive critical discussion within their groups and with their adversaries; as they struggle to develop governmental policies that would collectively support their and their oppositions political interests. Through this activity my students developed their cognitive skills, because they utilize historical evidence, such as the philosophies of the political and religious parties in India to create decisions that will have prolific social and political implications upon society. Through this simulation, students examined and comprehended the developmental stages of government policy, regardless if these policies were created in India and not in the United States. For instance, a group designed their central government, within the political framework of the United States. Imperatively, through their group deliberations, students not only evaluated the ideology of their parties, but also of the lawmaker, who arduously struggles to find possible resolutions to impossible issues. These young adults through this simulation exercise, became the actual policy makers, and become challenged by the political and religious issues in India, that still remain unresolved today. Subsequently, this particular aesthetic- based inquiry lesson inherently synthesizes the pedagogical ideologies of Dr. Wade’s (2008) service learning approach and Cornel West’s (2008) democratic paideia, since my students became inspired to pursue their civic involvement in the future, and have the education, experience, and passion to develop a more progressive democratic American society and international community(Robinson,2011).

Aesthetic-based teaching and learning practices within Advanced Placement History Courses can also contribute to the advancement of their academic performance in their Advanced Placement examinations. Within my AP World History Courses, ever since I started integrating the aesthetics four years ago within my instruction, I have identified significant one to point increase within my students’ examination scores. Concurrently, along with the aesthetics and questioning, the impact of my student’s scores also derived from their intensive writing. Along with questioning, the integral component of teaching history is writing. Intensive writing was another key feature of Nance’s instruction and the essential foci of Advanced Placement History examinations. In Nance’s course students independently and interdependently worked on essays, that he gave as assignments in advance so that they could formulate study groups (Yaeger & Davis, 2005). Nance also offered personal and public commentary to students about their essays; perceiving that through the discussion of his student’s weaknesses in writing they can autonomously and collectively improve their historical thinking and writing (Yaeger & Davis, 2005). Analogously to Nance’s (Yaeger & Davis, 2005) methodology another innovative aesthetic assignments that I integrate within my AP course having my students write weekly reflective journal entries of their academic triumphs, challenges, and personal interests within the AP course. During the closure of every Friday’s class, my students, through the means of critical dialectical discourse collectively discussed their journal entries with, myself and each other; critically reflecting and learning autonomously within an interdependent team of learners, that contributed to their overall intellectual and emotional excellence within the course. After the conclusion of each of my AP classes on Friday afternoons, I documented the strengths and weaknesses of each of my lessons in my academic journal, through the journal responses of my students. Through the documentation of my students’ journal entries, I aesthetically aspired to utilize my content reflection of my student journal entries as an instrument towards the development and reconstruction of my instructional methodology. Subsequently, I also applied my student’s journal responses as an instructional framework to design inquiry-based pedagogical activities that could explicate my student’s intellectual and emotional creativity; lessons that intertwined with their personal historical interests and develop their historical literacy. Comparatively, to Nance’s (Yaeger & Davis, 2005) study, Eisner states:

“Like the arts, the school curriculum is a mind-altering device; it is a vehicle that is designed to change the ways in which the young think…Each of the different art forms participates in a different history, has its own features, and utilizes different sensory modalities. By learning to create or perceive such forms, the arts contribute to the achievement of mind”. (Eisner, 1991, pg.16).

Within this discipline, arts-based integration students are not only expected to think like historians, but they are also able to distinguish between diverse historical sources and argue their evidence within Advanced Placement History courses. Lastly, through an inter-disciplinary art-based pedagogical approach, such as the one advocated by Eisner (1991), Epstein (1997), Laney (2007), and Greene (2018), within Advanced Placement History courses students will develop their high order historical thinking and writing skills and consequentially improve their examination scores, as my students have gradually accomplished.

Conclusion

“The successful search for knowledge requires the ability to analyze a line of reasoning and evaluate a work of art. It requires honesty, the willingness to question one’s beliefs, and the willingness to subordinate personal desires and preconceptions to the dictates of logic” (Markie, 2004, pg. 487). Aesthetic-based instruction provides an internal learning experience for the student, coercing them not only to academically excel in their AP History courses and examinations, but to also become present and future active civic and political members of their society. Correspondingly, Aesthetic-based instruction is also reflective of Cornel West’s (2008) concept of a democratic paideia; which is a form of education in which learners perceive themselves as agents of change; comprehending that they can make mistakes, learn from them, and consequently utilize that new-found knowledge to collectively empower their lives and the lives of others (West, 2013). Greene (2018), quoting Sartre states:

“at the heart of the aesthetic imperative is the moral imperative” because “the work of art, from whichever side you approach it (1949, pp.62-63) is an act of confidence in the freedom of human beings. We feel that freedom here—to interpret, to reflect, and (now and then) change our lives” (p.198).

Fundamentally, aesthetic education within Advanced Placement History courses will provide students with the skills of empirical and aesthetic excellence to restructure the ethical utilitarian framework of the international community; that is essentially embedded upon the socio-economic happiness and prosperity for all human beings. Through the ideals engrained by an aesthetic -based education the current trend of “The Millennial Generation insisting on solutions to accumulated problems and injustices, and an emerging Generation E calling for equilibrium” (Marx, 2006, p. 48) will be achieved through the disciplines of history, philosophy, literature, the visual arts, music, and religion (Sullivan & Rossin, 2008). Consequentially, students will apply their aesthetic knowledge within any career path they decide to embark upon in the future.

References

Aristotle (2007). “The Nicomachean Ethics”, p.143, Filiquarian Publishing, LLC

Brooks, S. (2013). Teaching for Historical Understanding in the Advanced Placement Program: A Case Study. The History Teacher, 47(1), 61-76.

California State University Sonoma. (2008). Cornel West. Retrieved from: www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ZzWWq_rQt8

Dewey, J. (1988). The Public and Its Problems: Athens, OH: Swallow Press.

Eisner, E. W. (1991). What the arts taught me about education. Art Education, 44(5), 10-19.

Epstein, T. (1997). Social Studies and the Arts. The Social Studies Curriculum, 235.

Greene, Maxine. (2001). Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute lectures on aesthetic education. New York: Teachers College Press

Markie, P. (1994). A professor’s duties: Ethical issues in college teaching. Lanham, MD: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Marx, G. (2006). Future focused leadership: Preparing schools, students, and communities for tomorrow’s realities. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Development.

McCrary, A. S. (2000). Notes from a marine biologist’s daughter: On the art and science of attention. Harvard Educational Review, 70, 211–227.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Robinson, K. (2011). Out of our minds: Learning to be creative. West Sussex, UK: Capstone Publishing Ltd.

Yaeger, E.A. & Davis, O.L. (Eds.). (2005). Wise social studies teaching in an age of high stakes testing: Essays on classroom practices and possibilities. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.