Fairness Counts: Integrating Math and Social Studies in the Elementary Classroom

Marilyn M. DePietto

“That’s not fair!” Any teacher who has spent time in elementary school classrooms knows the frequency and passion with which this sentence is declared each day. As early as 3 years of age, children have a developed sense of fairness that concerns not only allocation of materials, but also the distribution process (Englemann & Tomasello, 2019). This desire to regulate games, play, and sharing of resources in early childhood continues to develop through the elementary years, and it provides a remarkable opportunity for teachers to leverage the integration of mathematics and social studies.

Social studies standards in New York explicitly refer to “gathering, interpreting, and using evidence” and “chronological reasoning and causation” (New York State Education Department [NYSED], 2017a). The Next Generation Standards for Mathematical Practice include “Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others” and “Look for and make use of structure,” which refers to finding patterns over the course of time (NYSED, 2017b). The overlap between these two subjects, particularly in the early grades, is significant and useful in settling disputes of tangible fairness and in the upper elementary grades, in providing support for students to think about more abstract concepts of fairness and equity.

Math and social studies integration for early childhood (PK-2)

Most early childhood classrooms have objects that are in short supply and coveted by many children at once. Common ones might include the “good” bean bag chair for reading, the block corner, or the newest art supplies. Some teachers generate and implement systems for managing these situations so that students are treated fairly. Other teachers might feel that students ought to learn that sometimes they can’t get what they want and adopt mantras similar to “you get what you get, and you don’t get upset.”

Both teacher-imposed systems of fairness and teacher-imposed systems of control miss a crucial opportunity to allow students ownership of their class rules and also an opportunity to show how social studies and mathematics are integrated and relevant. Consider the example of the bean bag chair that, for some reason undiscernible to adults, students have decided is the “best” one. In the reading corner, despite the fact that there are four seemingly equivalent places to sit, one chair always causes an argument or a dash across the room to get there first. It is important for teachers to know that even if it seems not to make sense, children assign tremendous value to objects. In fact, studies have shown that even very young children view objects as extensions of self (Diesendruck & Perez, 2015). Leveraging this assigned significance into learning opportunities should be at the forefront of teacher’s agendas.

An interdisciplinary solution to the bean bag chair problem might begin by first naming the issue and helping children articulate their feelings and questions about it. Then, the teacher might set up a democratic process for students to share what they think are good solutions. There are many literary resources that would be good starting points for student participation. Fair Shares by Pippa Goodheart, Share and Take Turns by Cheri J. Meiners, and Friends Ask First by Alexandra Cassel are a few popular choices to anchor a discussion.

Once all students have had an opportunity to ask questions and share their ideas for a fair system, the teacher might consolidate all of the ideas into two or three options. It is important to explicitly model thinking critically about ideas of fairness for students to help them broaden their understanding and expose them to different points of view (Bjervås, 2017). Ideas elicited from early childhood students would likely come under a few different categories: 1) some kind of system where everyone gets the same amount of time 2) a taking turns system, where if someone else wants a turn, the person in the chair has to give it up 3) a Darwinian system that indicates something to the effect of whoever gets there first gets the chair, and 4) other less fair, or more difficult to articulate systems. Through questioning and debate facilitated by the teacher, students would likely come to the conclusion that the time system is fairest. In PK-2 classrooms, setting up a ballot measure and having students vote would be a clear way of establishing an example of the democratic process. Age-appropriate social studies concepts met during this process include gathering, interpreting and using evidence, chronological reasoning and causation, and civic participation (NYSED, 2017a).

After everyone has participated in this form of civic engagement, mathematics plays a larger part. The very process of counting and representing the results of voting is a mathematical concept. Using a Unifix cube or a similar concrete manipulative to represent each vote, students can stack them to construct a three-dimensional bar graph showing how many votes were cast for each option. This visual and tactile representation of the votes will make it clear to students the option with which more students agree. This representation itself ticks several boxes for mathematical standards and concepts appropriate for PK-2 classrooms.

Counting objects, sorting them into categories, arranging them in a line to assign ordinal numbers, comparing the quantity in each group by using words like more than or fewer, and representing data in a display and reading said display are all mathematics concepts that students should learn in early childhood grades (NYSED, 2017b). Research has long since established that students not only retain mathematics content more effectively but are also better able to transfer and apply skills they learned through the context of their own social and cultural values rather than word problems with “real world” situations involving carts full of watermelons from a textbook (Boaler, 1993; Lazic & Maričić, 2021; Taylor, 1989). Establishing classroom rules that are fair for everyone is a high priority for young students, and therefore the mathematics and social studies concepts associated with the construction of such a classroom will likely be learned deeply and effectively.

The idea of “fairness” holds within it the essence of “equality,” which is a mathematics concept that is tremendously important but often misunderstood, particularly in early childhood (Sophian, 2022). Furthermore, concepts of equal parts of a whole, equal groups of objects, and showing equal quantities in different ways are found throughout PK-2 math standards (NYSED, 2017b). To keep with the time in the bean bag chair example, this activity can be further developed by facilitating a discussion among students about how much time in the bean bag chair is fair. If independent reading time is 20 minutes, and there are 20 students in the class, one option that can be shown using concrete or digital manipulatives is for each student to get 1 minute per day in the chair. Most young children have not yet developed understanding of lengths of time, and understanding the duration of a minute is an important concept taught in the early grades.

Discussion and practical testing of this idea might lead students to the realization that a single minute is not enough time for quality reading and relaxing. Therefore, through discussion and some experimentation with manipulatives representing minutes, the teacher might suggest that only fewer people per day get to sit in the chair, but for a longer time, and ask students to try to come up with a system for keeping track of students and times.

Including this amount of thinking and discussion about the bean bag chair will likely result in taking several days to create and revise the plan. The time invested in having students involved with and responsible for making a fair system is easily justified by the lessons and concepts they will learn about mathematics, social studies, literacy, and collaboration. An additional benefit to facilitating a series of lessons like these is the reduction of students wondering “why do we need to know this?” The meaning behind the instruction is already implicit: students will develop the skills and capacity to eliminate fighting over the bean bag chair.

Math and social studies integration for upper elementary (3-6)

As students mature throughout elementary school activities and lessons like the one above might become less relevant; students become more capable of regulating fairness in social situations without adult intervention. Additionally, items like the bean bag chair or favorite toys might become less significant in upper elementary classrooms. However, there still exist many opportunities for students to integrate mathematics and social studies concepts to gain a better understanding of fairness in the world.

Gathering and examining evidence, constructing arguments, and critiquing the reasoning of others are skills that both mathematics and social studies standards mention explicitly (NYSED, 2107a, b). Common examples of how to integrate mathematics and social studies include examining percentages, reading and interpreting graphs and charts, and analyzing change over time. One facet that may not be traditionally examined thorough the lens of both mathematics and social studies is a calculation of the amount of voting power that citizens have in an indirect democracy.

While younger students are quick to point out “that’s not fair!” when tangible resources are inequitably distributed, older students should be encouraged to think critically about the fairness and equity in more abstract terms by systems of which they are a part (Lee et al., 2021). Elementary school students begin learning the structure of the United States government and have some understanding of what government representatives do. They are also beginning to develop understanding of fractions, extremely large and small numbers, and operations with these numbers. These sets of concepts can be integrated to give students real world understanding of the amount of power their votes have by exploring representative democracy.

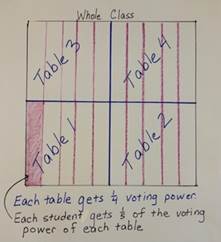

This activity focuses on U.S. Senate representation. If students are unfamiliar with representative democracy, a teacher might want to demonstrate using a concrete example with students in the class: If students in a class of 20 are seated 5 to a table, for example, an election for table representative can be held. Students should understand that these representatives will, with the direction of the teacher, help make some of the rules for the classroom and advocate on behalf of their constituents (tablemates). Therefore, they have to think carefully about who they want to represent them. In this example, there are 4 student representatives who will be part of the discussion and vote on rules. Each of these student representatives, therefore, has of the total voting power in any matter on which they vote.

The next question is, how much voting power does each person at the table have? By facilitating discussion, the teacher should be able to elicit that each student has of the voting power, since everyone was able to vote for their own representative. This can be found two ways; the first one indicated below is the most straightforward, while the second might be less obvious. Nevertheless, students might notice and articulate this strategy if they are given the chance to explore it. This is also the skill students will need to find answers to questions later in this activity.

- Each student is 1 out of the total 20 in the class, therefore each vote is

of the total.

- Each table gets

of the vote via their representative. That

of the vote comprises 5 students, so each student gets

of that

. Students can draw a model of fourths, then divide each of those fourths into 5 sections (Figure 1) to show that every smaller section is then

. Some students might realize that

of

also means

, which is also the same as

.

Figure 1

The reasoning in the second explanation can be further explored by changing some conditions about the representatives. For example, what if there were still 4 tables, each with 1 representative, but one table had 8 people, and the rest had 4? Would everyone still have the same voting power? The table of 8 would have of the voting power each. While the tables of 4 would have

of the voting power each. There are several mathematical questions that can be asked at this point to facilitate exploration with fractions:

- Who has more voting power? How do you know?

- Is that fair? Which table would you want to sit at?

- What does the size of the denominator tell us about the size of the fraction?

This activity can be extended over the course of several days to expand students’ understanding of voting power on a larger scale. They can be asked to find reliable sources of information indicating the population of each state in the U.S. and to calculate the voting power of the citizens of each state in the U.S senate if each state is represented by two senators. These calculations would involve operations with very large numbers, and comparing unit fractions that represent extremely small quantities, both of which are included in upper elementary mathematics standards (NYSED, 2017a). Students might be surprised to learn that in terms of senate votes, U.S. citizens have drastically different voting power. Extension questions might include:

- Citizens of which state have the most voting power in the senate? The least?

- How many times as powerful are the votes from the state with the most power per citizen compared with the state with the least?

- Is this the case in all branches of government? Should it be? How does representation in the other branches work?

Conclusion

Both the activity described for PK-2 students and the one described for upper elementary students integrate mathematics and social studies in an age-appropriate, real-world context. Social studies and mathematics are not always considered easy to integrate smoothly, but many concepts and skills are clearly interdisciplinary between these two subjects. While meeting content standards is important to ensure equity of mathematics and social studies knowledge among students, it is even more important to give students the tools to think critically, advocate for themselves, and engage in civil discourse (Lee, et al. 2021). These skills ought to be taught through relevant applications that demonstrate to students why it is important to have them. For this reason, leveraging students’ deeply developed feelings that some things are unfair (Engelmann & Tomasello, 2019) into motivating lessons about how to quantify fairness and equity is a powerful bit of pedagogy.

References

Boaler, J. (1993). The Role of Contexts in the Mathematics Classroom: Do they Make Mathematics More” Real”? For the learning of mathematics, 13(2), 12-17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40248079

Bjervås, L. L. (2017). Teaching about fairness in a preschool context. In Values in Early Childhood Education (pp. 55-69). Routledge.

Diesendruck, G., & Perez, R. (2015). Toys are me: Children’s extension of self to objects. Cognition, 134, 11-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.09.010

Engelmann, J. M., & Tomasello, M. (2019). Children’s sense of fairness as equal respect. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(6), 454-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.03.001

Lazic, B., Knežević, J., & Maričić, S. (2021). The influence of project-based learning on student achievement in elementary mathematics education. South African Journal of Education, 41(3). http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.hofstra.edu/10.15700/saje.v41n3a1909

Lee, C. D., White, G., & Dong, D. (2021). Educating for Civic Reasoning and Discourse. National Academy of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED611951.pdf

New York State Education Department. (2017a). New York State K-8 social studies framework.https://www.nysed.gov/sites/default/files/programs/standards-instruction/ss-framework-k-8a2.pdf

New York State Education Department. (2017b). New York state p-12 learning standards for mathematics. http://www.nysed.gov/new-york-state-revised-mathematics-learning-standards

Sophian, C. (2022). A developmental perspective on children’s counting. The development of mathematical skills (pp. 26-46). Psychology Press.

Taylor, N. (1989). Let them eat cake: desire, cognition and culture in mathematics learning. Mathematics for All, 161-163.