United States Foreign Policy History and Resource Guide

Roger Peace

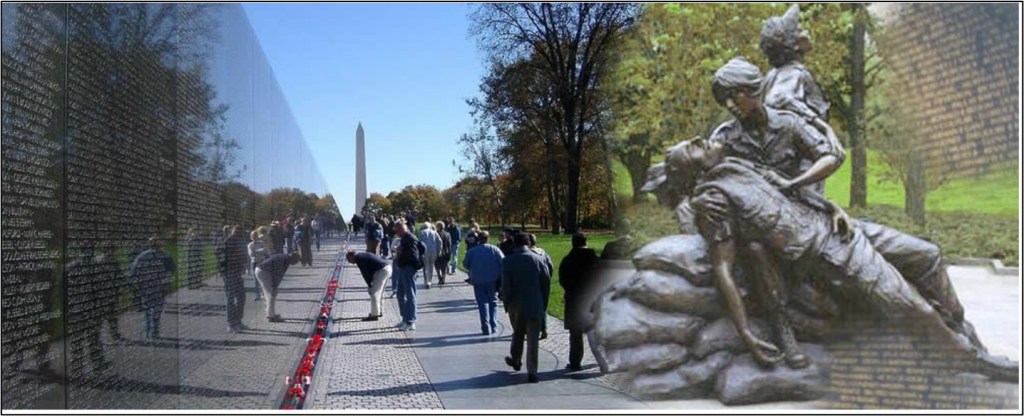

The Vietnam Memorial Wall and Women’s Memorial statue in Washington DC.

This website is designed with three purposes in mind. One is to provide a coherent overview of United States foreign policies, covering the nation’s wars, military interventions, and major doctrines over the course of some 250 years. While written for the general public and undergraduate students, it can be adapted for use in high schools. Each entry draws on the work of experts in the area of study, summarizing major developments, analyzing causes and contexts, and providing links to additional information and resources.

The second purpose is to examine great debates over U.S. foreign policies and wars, focusing especially on leaders and movements advocating peace and diplomacy. Controversy has been the hallmark of U.S. foreign policy from the War for Independence to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 21st century.

The third purpose is to evaluate U.S. foreign policies and wars from a principled perspective, one that reflects “just war” and international humanitarian norms today. This is a history about the United States’ role in the world, but it does not define “success” and “progress” in terms of the advancement of national power and interests, even the winning of wars.

The website was launched in October 2015 by Roger Peace. The Historians for Peace and Democracy became a sponsor the following month, and the Peace History Society, in June 2016. Contributors include Brian D’Haeseleer, Assistant Professor of U.S. History at Lyon College; Charles Howlett, Professor of Education Emeritus at Molloy College; Jeremy Kuzmarov, managing editor for CovertAction Magazine; John Marciano, Professor Emeritus at the State University of New York at Cortland; Anne Meisenzahl, a adult education teacher; Roger Peace, author of A Call to Conscience: The Anti-Contra War Campaign; Elizabeth Schmidt, Professor Emeritus of history at Loyola University Maryland; and Virginia Williams, director of the Peace, Justice, & Conflict Resolution Studies program at Winthrop University.

The website has a Chronology of U.S. Foreign Policy, 1775-2021 with links to pages with documents from the War of 1812 through the 21st century “War on Terror.”

There is no shortage of books, articles, and websites addressing the history of United States foreign policy. There is nevertheless, within the United States, a dearth of understanding and often knowledge about the subject. This is due in part to popular nationalistic history, which tends to obscure, overwrite, and sometimes whitewash actual history.

The central assumption of this celebratory national history is that America “has been a unique and unrivaled force for good in the world,” as the historian Christian Appy described it. This assumption underpins the more muscular belief that the more power the U.S. acquires and wields in the world, the better. In other words, the U.S. should rightfully be the dominant military power in the world, given its benefic intentions and noble ideals. This flattering self-image is often buttressed by depictions of America’s opponents as moral pariahs – aggressors, oppressors, “enemies of freedom.”

Celebratory national history is deeply rooted in American culture. As may be seen in the second sentence of the war memorial below, American armed forces are typically portrayed as fighting “the forces of tyranny” and upholding the principles of liberty, dignity, and democracy.

America’s opposition to “tyranny” has a long ideological pedigree. In the Declaration of Independence of 1776, Patriot rebels denounced the King of Great Britain for “repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.” In fact, the British objective was to raise revenue from the colonies and curtail their smuggling. However oppressive particular acts, the British government was nonetheless the most democratic in Europe, with an elected House of Commons and established rights for Englishmen that had evolved over a 600-year period. The new American government continued to build on this democratic tradition, as did the British themselves. The idea that America represented “freedom” as opposed to “tyranny” nonetheless became an ideological fixture in the new nation, invoking a virtuous and noble national identity.

In its second 100 years of existence, the United States became a world power, joining the ranks of Old World empires such as Great Britain. As the U.S. prepared to militarily intervene in Cuba and the Philippines in 1898, President William McKinley declared, “We intervene not for conquest. We intervene for humanity’s sake” and to “earn the praises of every lover of freedom the world over.” Most lovers of freedom, however, denounced subsequent U.S. actions. The U.S. turned Cuba into an American “protectorate,” and the Philippines into an American colony. Rather than fighting to uphold freedom, the U.S. fought to suppress Filipino independence – at a cost of some 200,000 Filipino and 4,300 American lives.

A half-century later, at the outset of the Cold War, President Harry Truman asserted that the United States must “support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” Truman highlighted the tyranny of the Soviet Union and its alleged threat to Greece and Turkey, but he utterly ignored the more widespread tyranny of European domination over most of Asia and Africa. In the case of Vietnam, the U.S. opted to side with the oppressor, aiding French efforts to re-conquer the country. Truman’s fateful decision in 1950 led to direct U.S. involvement in Vietnam fifteen years later.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy famously proclaimed that the United States would “pay any price, bear any burden . . . to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” These appealing words reminded Americans of their mythic moral identity, but they hardly guided U.S. foreign policy. During the long Cold War (1946-91), the U.S. provided military and economic aid to a host of dictatorial and repressive regimes, including those in Cuba (before Fidel Castro assumed power), Nicaragua, Haiti, Guatemala, El Salvador, Argentina, Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, Zaire, Somalia, South Africa, Turkey, Greece, Iran, Pakistan, Indonesia, South Korea, South Vietnam, and the Philippines. The U.S. also employed covert action to help overthrow democratically elected governments in Iran, Guatemala, and Chile. Despite propping up authoritarian governments and undermining democratic ones, U.S. leaders described their allies as the “free world.”

In the 21st century, the rhetoric of fighting tyranny and upholding freedom has been grafted onto the “War on Terror,” declared by President George W. Bush in the wake of terrorist attacks in the U.S. on September 11, 2001. The attacks were carried out by individuals from Saudi Arabia and other friendly Arab states, but Bush directed public fears and anger toward wars against Afghanistan and Iraq. Unable to find weapons of mass destruction or ties to al Qaeda in Iraq, Bush reverted to the standard American rationale – promoting freedom. “As long as the Middle East remains a place where freedom does not flourish,” he declared on November 7, 2003, “it will remain a place of stagnation, resentment and violence ready for export.”

Today, the U.S. is the world’s sole “superpower,” with the largest military budget, the most sophisticated weaponry, a network of over 700 military bases worldwide, and the capability to militarily intervene in other nations at will. The latter includes the frequent use of armed drones to assassinate suspected terrorists in countries with which the U.S. is not at war. Americans on the whole do not regard this overwhelming military power as a threat to other nations or global stability. British historian Nial Ferguson has commented that the “United States is an empire in every sense but one, and that one sense is that it doesn’t recognize itself as such.” The diplomatic historian William Appleman Williams described this dominant American worldview as “imperial self-deception.”